Marketing Ethics to Social Marketers: a Segmented Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lawyer Communications and Marketing: an Ethics Primer

LAWYER COMMUNICATIONS AND MARKETING: AN ETHICS PRIMER Hypotheticals and Analyses* Presented by: Leslie A.T. Haley Haley Law PLC With appropriate credit authorship credit to: Thomas E. Spahn McGuireWoods LLP Copyright 2014 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Hypo No. Subject Page Standards for Judging Lawyer Marketing 1 Possible Sanctions ....................................................................................... 1 2 Constitutional Standard ............................................................................... 8 3 Reach of State Ethics Rules: General Approach ...................................... 33 4 Reach of State Ethics Rules: Websites ..................................................... 38 General Marketing Rules: Content 5 Prohibition on False Statements ................................................................. 42 6 Self-Laudatory and Unverifiable Claims ..................................................... 49 7 Depictions ..................................................................................................... 65 8 Testimonials and Endorsements................................................................. 72 Law Firm Marketing 9 Law Firm Names ........................................................................................... 80 10 Law Firm Trade Names and Telephone Numbers ...................................... 100 11 Law Firm Associations and Other Relationships ...................................... 109 Individual Lawyer Marketing 12 Use of Individual Titles ................................................................................ -

Marketing to Patients: a Legal and Ethical Perspective

Marketing to Patients: A Legal and Ethical Perspective Deborah M. Gray PhD Central Michigan University [email protected] Linda Christiansen, JD MBA Indiana University Southeast [email protected] ABSTRACT Medical practices and other healthcare providers are frequently reluctant to use medical records in marketing as a result of misconceptions regarding HIPAA law. Healthcare providers should have no qualms about using medical records or offering a service such as email for communication with patients for fear of violating HIPAA. Their concerns should lie only within the concerns for ethical online marketing, albeit with a greater sensitivity for how patients might react to usage of what is considered by many to be very private information. Keywords: Marketing, Ethics, HIPAA, Healthcare, Professional Codes of Ethics Marketing to Patients Journal of Academic and Business Ethics 69 Introduction The healthcare industry appears to be avoiding use of email and Web marketing as a result of concerns regarding HIPAA restrictions and warnings from insurers not to engage in electronic communication with consumers (Landro, 2002). In this paper we address the use of electronic marketing strategies (email marketing, online scheduling, etc.) in the healthcare field within the confines of the HIPPA law and industry- recommended ethical guidelines. Offering these customer-oriented services can be a strategic use of the Internet for marketing to current patients, attracting new patients, and reducing costs. Web and email marketing are ripe marketing options for medical practices because consumers are increasingly using the Internet as a means of searching for information about their health concerns (HarrisInteractive, 2007). Today’s patients are very interested in being able to contact their physician by email to schedule appointments and/or ask questions (HarrisInteractive, 2007). -

Session 9 Ethics.Pdf

E t h i c s | 1 Session 9 4.3. Marketing Ethics Marketing ethics is the area of applied ethics which deals with the moral principles behind the operation and regulation of marketing. Some areas of marketing ethics (ethics of advertising and promotion) overlap with media ethics. Fundamental issues in the ethics of marketing Value-oriented framework, analyzing ethical problems on the basis of the values which they infringe (e.g. honesty, autonomy, privacy, transparency). An example of such an approach is the AMA Statement of Ethics. Stakeholder-oriented framework, analyzing ethical problems on the basis of which they affect (e.g. consumers, competitors, society as a whole). Process-oriented framework, analyzing ethical problems in terms of the categories used by marketing specialists (e.g. research, price, promotion, placement). None of these frameworks allows, by itself, a convenient and complete categorization of the great variety of issues in marketing ethics. Power-based analysis Contrary to popular impressions, not all marketing is adversarial, and not all marketing is stacked in favor of the marketer. In marketing, the relationship between producer/consumer and buyer/seller can be adversarial or cooperative. For an example of cooperative marketing, see relationship marketing. If the marketing situation is adversarial, another dimension of difference emerges, describing the power balance between producer/consumer and buyer/seller. Power may be concentrated with the producer (caveat emptor), but factors such as over-supply or legislation can shift E t h i c s | 2 the power towards the consumer (caveat vendor). Identifying where the power in the relationship lies and whether the power balance is relevant at all are important to understanding the background to an ethical dilemma in marketing ethics. -

The Ethics of Advertising for Health Care Services Yael Schenker, University of Pittsburgh Robert M

The American Journal of Bioethics, 14(3): 34–43, 2014 Copyright c Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1526-5161 print / 1536-0075 online DOI: 10.1080/15265161.2013.879943 Target Article The Ethics of Advertising for Health Care Services Yael Schenker, University of Pittsburgh Robert M. Arnold, University of Pittsburgh Alex John London, Carnegie Mellon University Advertising by health care institutions has increased steadily in recent years. While direct-to-consumer prescription drug adver- tising is subject to unique oversight by the Federal Drug Administration, advertisements for health care services are regulated by the Federal Trade Commission and treated no differently from advertisements for consumer goods. In this article, we argue that decisions about pursuing health care services are distinguished by informational asymmetries, high stakes, and patient vulner- abilities, grounding fiduciary responsibilities on the part of health care providers and health care institutions. Using examples, we illustrate how common advertising techniques may mislead patients and compromise fiduciary relationships, thereby posing ethical risks to patients, providers, health care institutions, and society. We conclude by proposing that these risks justify new standards for advertising when considered as part of the moral obligation of health care institutions and suggest that mechanisms currently in place to regulate advertising for prescription pharmaceuticals should be applied to advertising for health care services more broadly. Keywords: media, organizational -

Ethical Marketing

RESEARCH PAPER Management Volume : 3 | Issue : 7 | July 2013 | ISSN - 2249-555X Ethical Marketing KEYWORDS Marketing Ethics, Marketing Mix, promotions. Integrity A. R Kanagaraj G.Geetha S.Archana Assistant professor, Department Assistant professor, Department Assistant professor, Department of corporate secretaryship, Dr. of corporate secretaryship, Dr. of corporate secretaryship, Dr. N.G.P Arts and science college, N.G.P Arts and science college, N.G.P Arts and science college, Coimbatore-48 Coimbatore-48 Coimbatore-48 ABSTRACT The major purpose of this research was to study the level of science interest of higher secondary school stu- dents. The data were collected by means of science interest of higher secondary school students constructed by N.O. Nellaiyappan scale have been administered to a random sample of 300 higher secondary school students in Din- digal District. The normative survey method has been used. The collected data were subjected to ‘t’ test and ‘F’ test for large independent groups. The findings indicate there is a significant difference in the level of science interest between the urban and rural students and the type of management. But there is no significant difference in the level of science interest between boys and girls, parents occupation and parents education. What is ethics? • Refrain from advertising falsely and misleading Ethics are the moral principles and values that govern the consumers actions and decisions of an individual or group. They serve • Maintain market research integrity by adhering to as guidelines on how to act rightly and justly when faced with market research guidelines moral dilemmas. • Respect consumers privacy rights and ensure con fidentiality of information Definition of marketing ethics: • Adhere to standards and guidelines of internation Ethical marketing refers to the application of marketing eth- al marketing associations and to the legal ics into the marketing process. -

Ethical Marketing Communication in the Era of Digitization/Kuldeep Brahmbhatt

EthicalVolume 7 Issue 2 Marketing Communication inJuly - Decemberthe 2015 Era of Digitization Kuldeep Brahmbhatt Abstract attracts attention and stimulates the intention to purchase. The modes of communication have undergone The present paper focuses on the consideration of ethics changes over a period of decades in line with in marketing communication. Recently, Lenskart, technological reforms, economic changes, changes in American Swan and Trioka made promotional brand the operating environment of the business and most communication on the day of the Nepal earthquake to importantly, customer expectations. In the last decade, exploit business leverage. This faced criticism on various digitization has revolutionized marketing media platforms for insensitivity of the communication communication. Aaker (2015) noticed that digital piece. Author identified various factors which may lead marketing communication is a powerful device for to such insensitive communication which includes, building brands and strengthening the relationship with organizational policies, role of educational institutes in individuals and community by engaging them actively moral development, cognitive moral upbringing of in the marketing process. He also adds that such active individual, individual personality traits, intentions of participation has led the marketer to communicate the the message and competitive environment. In addition message at individual level with rich and deep content. it explains, how brands handle image management once In a way, the digital platform has given the marketer it has been damage. A few components of Image Repair an option for greater reach with more customized Theory such as, mortification, evasion of responsibility offerings. and reduction in the offensiveness of the act have been used to restore the image. -

IJESM Volume 3, Issue 4 ISSN

February 2012 IJRSS Volume 2, Issue 1 ISSN: 2249-2496 ‘’Business Ethics and Thirukkural Values’’ Dr. Mohammed Galib Hussain P. Pugazhendhi, UGC – Emeritus Professor and Rector Ph, D Research Scholar, Islamiah College, Vaniyambadi 635 752. Islamiah College, Vaniyambadi 635 752. Abstract Business ethics is a growing and developing discipline. Generally, it is believed that business ethics involves adhering to legal, regulatory, professional promises and commitments and abiding by general principles like fairness, truth, honesty and respect. It has take the part of dimensions of Business Ethics like HRM, Finance, Production, Marketing, Advertising and Corporate Social Responsibilities–Thirukkural and its Origin –Values in Thirukkural–Relevance of Thirukkural to Dravidian Culture–Thirukkural and Various dimensions of Business Ethics.. Key word: Ethics, Business, Thirukkural, Personal Values, Dravidians Culture. INTRODUCTION The concept of ethics comes from the Greek word ―ethos‖ that means both an individual‘s character and a community‘s culture Ethics simply shows you what is good and what is bad and what is right and what is wrong. Tenets of business ethics operate as system of values that are concerned primarily with the relationship of business goals to human ends; Business ethics has a five-part structure: 1. The specification of moral judgment 2. Moral judgment and the moral standard 3. justification of moral judgment 4. Logical reasoning and moral judgment 5. Moral judgment and moral responsibility. 6. A Quarterly Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International e-Journal - Included in the International Serial DirectoriesIndexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A.,Open J-Gage, India as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A. -

Ethical Considerations

05-Polonski.qxd 6/2/04 4:41 PM Page 53 5 Ethical Considerations he consideration of ethics in research, and in general business for that T matter, is of growing importance. It is, therefore, critical that you understand the basics of ethical research and how this might affect your research project. This is especially important if your research involves inter- action with businesses or members of the general community who serve as participants (i.e., respondents) in your research. There are a range of inter- actions in your research that might occur, including in-depth interviews, focus groups, surveys, or even observing people’s behavior. Though all researchers (student, professional, or academic) are well inten- tioned, there is the possibility that interaction with participants may inadver- tently harm them in some unintended way. This could include • Psychological harm—for example, researching the use of nudity in advertising may show participants images that offend them. • Financial harm—researching unethical behavior within a given firm may provide management with information on individual employees that results in an individual getting fired, or undertaking industry- based research may inadvertently share sensitive information with a firm’s competitors, resulting in financial harm to the organization. • Social harm—researching how lifestyle affects consumption may unintentionally disclose a person’s sexual orientation when that person wanted to keep this confidential. It is your responsibility to consider whether any type of harm -

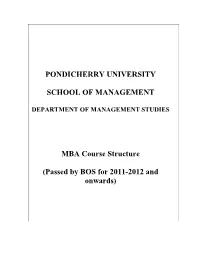

MBA Course Structure (Passed by BOS for 2011-2012 and Onwards)

PONDICHERRY UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES MBA Course Structure (Passed by BOS for 2011-2012 and onwards) INDEX CONTENT PAGE No. COURSE STRUCTURE OF M.B.A. PROGRAMME 1 M.B.A. REGULATIONS 2 SEMESTER I – SYLLABUS 6 SEMESTER II – SYLLABUS 23 SEMESTER III – SYLLABUS 41 SEMESTER IV – SYLLABUS 51 ELECTIVES – SEMESTER III AND SEMESTER IV 55 MARKETING ELECTIVES – SYLLABUS 57 FINANCE ELECTIVES – SYLLABUS 85 HRM ELECTIVES – SYLLABUS 118 OPERATIONS ELECTIVES – SYLLABUS 142 SYSTEMS ELECTIVES – SYLLABUS 159 GENERAL ELECTIVES – SYLLABUS 177 COURSE STRUCTURE OF M.B.A. PROGRAMME IN PONDICHERRY UNIVERSITY MBA COURSE STRUCTURE SEMESTER – I SEMESTER – II Subject Credit Marks Subject Credit Marks Management Processes 3 100 Project Management 3 100 Organisational Behaviour 3 100 Financial Management 3 100 Managerial Economics 3 100 Operations Research 3 100 Accounting for Managers 3 100 Business Law 3 100 Statistics & Research 3 100 Marketing Management 3 100 Methodology Business Environment 3 100 Operations Management 3 100 Communication skills 2 50 Human Resources Management 3 100 workshop Systems skills workshop 2 50 Management Information 3 100 Systems Comprehensive Viva-Voce 2 50 Comprehensive Viva-Voce 2 50 Total 24 750 Total 26 850 SEMESTER – III SEMESTER – IV Subject Credit Marks Subject Credit Marks Strategic Management 3 100 Public Systems Management 3 100 Business Ethics & Corporate 3 100 Functional Electives (4) 12 400 Governance Quality Management 3 100 Project Work (10 Weeks) (150 5 200 Marks for thesis + 50 marks for Project Viva) Management Control 3 100 Comprehensive Viva-Voce 2 50 Systems Functional Electives (4) 12 400 Summer Projects (8 Weeks) 4 150 (100 Marks for thesis + 50 Marks for Project Viva) Comprehensive Viva-Voce 2 50 Total 30 1000 Total 22 750 Total Number of Credits : 102 Total marks : 3,350 Total Number of theory paper : 27 Total Number of Skills development workshop: 2 Total Number of Comprehensive Viva : 4 Number of projects : 2 1 M.B.A. -

MGT-301 Principle of Marketing 1000 Solved MCQ an Overview of Strategic Marketing Section A

Composed By Sehrish Naz MGT-301 Principle of Marketing 1000 Solved MCQ An Overview of Strategic Marketing Section A 1) Marketing is best defined as: A) matching a product with its market. B) promoting and selling products. C) facilitating satisfying exchange relationships. D)distributing products at the right price to stores. 2) The expansion of the definition of marketing to include nonbusiness activities adds which one of these examples to the field of marketing? A)Proctor and Gamble selling toothpaste. B)St. Pauls Church attracting new members. C)PepsiCo selling soft drinks. D)Lever's donating 25 pence to a charity with every pack purchased. 3) Tom goes to a vending machine, deposits 50 pence, and receives a Cola. Which one of the following aspects of the definition of marketing is focused on here? A)Production concept. B)Satisfaction of organisational goals. C)Product pricing and distribution. D)Exchange. 4) The marketing environment is BEST described as being: A)composed of controllable variables. B)composed of variables independent of one another. C)an indirect influence on marketing activity. D)dynamic and changing. 5) A physical, concrete product you can touch is: A)a service B)a good VU Cafeteria C)an idea D)a concept E)a philosophy 6) Chimney Sweeps employs people to clean fireplaces and chimneys in homes and apartments. The firm is primarily the marketer of: A)a service B)a good C)an idea D)an image E)a physical entity Note: This is only a helping material VU Cafetria is not resposible for any solved content Composed By Sehrish Naz 7) Which one of the following statements by a company chairman best reflects the marketing concept? A)We have organised our business to make certain that we satisfy customer needs. -

The Relationship Between Marketing Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility: Serving Stakeholders and the Common Good Gene R

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Marketing Faculty Research and Publications Marketing, Department of 1-1-2016 The Relationship Between Marketing Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility: Serving Stakeholders and the Common Good Gene R. Laczniak Marquette University, [email protected] Patrick E. Murphy University of Notre Dame Published version. "The Relationship Between Marketing Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility :Serving Stakeholders and the Common Good" in Handbook of Research on Marketing and Corporate Social Responsibility, edited by Ronald Paul Hill and Ryan Langan. Cheltenham, UK ; Northampton, MA : Edward Elgar, 2016: 68-87. Publisher link. © 2016 Edward Elgar. Used with permission. Source: Ronald Paul Hill and Ryan Langan (2014), Handbook ofResearch on Marketing and Corporate Social Responsibility, Edward Elgar, pp. 68-87. 3. The relationship betweep marketing ethics and corporate social-responsibility: serving stakeholders and the common good Gene R. Laczniak and Patrick E. Murphy Marketing ethics (ME) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) are related concepts that often cause definitional confusion among academ ics attempting to analyze social issues in marketing. The same linguistic obstacles confound public policy makers when they suggest regulatory adjustments to market sectors, especially when they invoke descriptors couched in ethical or socially responsible phraseology. Academic research ers also regularly struggle with the ME and CSR terminology due, in part, to confusion deriving from the 'level of analysis' that is being addressed, (manager's focus versus firm-centered orientation). The purpose of this chapter is to explore the concepts of ME and CSR, establish their relative relations.hip and, in so doing, develop deeper insights about how these two constructs strategically connect. -

Ethical Marketing Controversial Products and Promotional Practices

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 4-1-2007 Ethical Marketing Controversial Products and Promotional Practices Jared D. Cohen Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Management Sciences and Quantitative Methods Commons, and the Marketing Commons Recommended Citation Cohen, Jared D., "Ethical Marketing Controversial Products and Promotional Practices" (2007). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 596. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/596 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract In the field of business ethics, there has been much written and discussed about ethical matters in areas where there is a distinct right and wrong, but relatively little written about how to make decisions when the ethical issue isn’t as black and white. When marketing a product, it is one’s hope that ethical issues are typically not inherent to the marketer; however, when one has the unenviable task of marketing a controversial product, it becomes a true question of “gray- area” ethics that makes marketing decisions more difficult to make. Companies depend on marketing, as it is the one higher-level areas of corporate function that results in the sales of the actual product. In this particular situation, it becomes increasingly difficult for a marketer to make decisions about how to ethically promote their product to their customers while still being ethical in the decisions made.