Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

App. 12 – EPBC Act Protected Matters Report and Wildlife Online

Environmental Impact Statement - VOLUME 3 Appendix 12 EPBC Act Protected Matters Report and Wildlife Online PR100246 / R72894; Volume 3 EPBC Act Protected Matters Report This report provides general guidance on matters of national environmental significance and other matters protected by the EPBC Act in the area you have selected. Information on the coverage of this report and qualifications on data supporting this report are contained in the caveat at the end of the report. Information is available about Environment Assessments and the EPBC Act including significance guidelines, forms and application process details. Report created: 26/09/13 12:19:15 Summary Details Matters of NES Other Matters Protected by the EPBC Act Extra Information Caveat Acknowledgements This map may contain data which are ©Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia), ©PSMA 2010 Coordinates Buffer: 10.0Km Summary Matters of National Environmental Significance This part of the report summarises the matters of national environmental significance that may occur in, or may relate to, the area you nominated. Further information is available in the detail part of the report, which can be accessed by scrolling or following the links below. If you are proposing to undertake an activity that may have a significant impact on one or more matters of national environmental significance then you should consider the Administrative Guidelines on Significance. World Heritage Properties: None National Heritage Places: None Wetlands of International Importance: None Great Barrier Reef Marine Park: None Commonwealth Marine Areas: None Listed Threatened Ecological Communities: 2 Listed Threatened Species: 47 Listed Migratory Species: 16 Other Matters Protected by the EPBC Act This part of the report summarises other matters protected under the Act that may relate to the area you nominated. -

Australian Natural History Australian Natural History Published Quarterly by the Australian Museum, 6-8 College Street, Sydney

AUSTRALIAN NATURAL HISTORY AUSTRALIAN NATURAL HISTORY PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM, 6-8 COLLEGE STREET, SYDNEY. TRUST PRESIDENT, JOE BAKER. MUSEUM DIRECTOR, DESMOND GRIFFIN VOLUM E 20 NUMBER 6 1981 This sun orchid, known as Thelymitra Altocumulus developed from a sheet of altostratus provided this memorable dawn near Mt Watt, truncata, is thought to be a natural hybrid Central Australia. Photo Robert Jones. between two commoner species, T. ixioides and T. pauciflora (or T. nuda). Obviously hybridisation is an uncommon or local phenomenon, or the parent species would lose their distinctness. Photo D. McAlpine. EDITOR CONTENTS Roland Hughes FROM THE INSIDE 173 ASSISTANT EDITOR Editorial Barbara Purse CIRCULATION PAGEANTRY IN THE SKIES 175 Bruce Colbey by Julian Hollis AMAZING ORCHIDS OF SOUTHERN AUSTRALIA 181 by David McAlpine Annual Subscription: Australia, $A8.00; New MAMMALS FOR ALL SEASONS 185 Zealand, $NZ11.50; other countries, $A9.50. by Roland Hughes Single copies: Australia, $A2.20, $A2.65 posted; New Zealand, $NZ3.00; other countries, $A3.40. COMMON BENT-WING BAT, Miniopterus schreibersii 187 For renewal or subscription please forward the Centrefold appropriate cheque/money order or bankcard number and authority made payable to Australian Natural History, the Australian Museum, PO Box A LOOK AT THE DINGO 191 A285, Sydney South 2001. by Bob Harden New Zealand subscribers should make cheque or money order payable to the New Zealand Govern DINOSAUR DIGGING IN VICTORIA 195 ment Printer, Private Bag, Wellington. by Timothy Flannery and Thomas Rich Subscribers from other countries please note that moneys must be paid in Australian currency. IN REVIEW 199 Opinions expressed by the authors are their own and do not necessarily represent the policies or GOOD THINGS GROW IN GLASS 201 views of the Australian Museum. -

Orchid Historical Biogeography, Diversification, Antarctica and The

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2016) ORIGINAL Orchid historical biogeography, ARTICLE diversification, Antarctica and the paradox of orchid dispersal Thomas J. Givnish1*, Daniel Spalink1, Mercedes Ames1, Stephanie P. Lyon1, Steven J. Hunter1, Alejandro Zuluaga1,2, Alfonso Doucette1, Giovanny Giraldo Caro1, James McDaniel1, Mark A. Clements3, Mary T. K. Arroyo4, Lorena Endara5, Ricardo Kriebel1, Norris H. Williams5 and Kenneth M. Cameron1 1Department of Botany, University of ABSTRACT Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, Aim Orchidaceae is the most species-rich angiosperm family and has one of USA, 2Departamento de Biologıa, the broadest distributions. Until now, the lack of a well-resolved phylogeny has Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia, 3Centre for Australian National Biodiversity prevented analyses of orchid historical biogeography. In this study, we use such Research, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia, a phylogeny to estimate the geographical spread of orchids, evaluate the impor- 4Institute of Ecology and Biodiversity, tance of different regions in their diversification and assess the role of long-dis- Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, tance dispersal (LDD) in generating orchid diversity. 5 Santiago, Chile, Department of Biology, Location Global. University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA Methods Analyses use a phylogeny including species representing all five orchid subfamilies and almost all tribes and subtribes, calibrated against 17 angiosperm fossils. We estimated historical biogeography and assessed the -

BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION on the TIWI ISLANDS, NORTHERN TERRITORY: Part 1. Environments and Plants

BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION ON THE TIWI ISLANDS, NORTHERN TERRITORY: Part 1. Environments and plants Report prepared by John Woinarski, Kym Brennan, Ian Cowie, Raelee Kerrigan and Craig Hempel. Darwin, August 2003 Cover photo: Tall forests dominated by Darwin stringybark Eucalyptus tetrodonta, Darwin woollybutt E. miniata and Melville Island Bloodwood Corymbia nesophila are the principal landscape element across the Tiwi islands (photo: Craig Hempel). i SUMMARY The Tiwi Islands comprise two of Australia’s largest offshore islands - Bathurst (with an area of 1693 km 2) and Melville (5788 km 2) Islands. These are Aboriginal lands lying about 20 km to the north of Darwin, Northern Territory. The islands are of generally low relief with relatively simple geological patterning. They have the highest rainfall in the Northern Territory (to about 2000 mm annual average rainfall in the far north-west of Melville and north of Bathurst). The human population of about 2000 people lives mainly in the three towns of Nguiu, Milakapati and Pirlangimpi. Tall forests dominated by Eucalyptus miniata, E. tetrodonta, and Corymbia nesophila cover about 75% of the island area. These include the best developed eucalypt forests in the Northern Territory. The Tiwi Islands also include nearly 1300 rainforest patches, with floristic composition in many of these patches distinct from that of the Northern Territory mainland. Although the total extent of rainforest on the Tiwi Islands is small (around 160 km 2 ), at an NT level this makes up an unusually high proportion of the landscape and comprises between 6 and 15% of the total NT rainforest extent. The Tiwi Islands also include nearly 200 km 2 of “treeless plains”, a vegetation type largely restricted to these islands. -

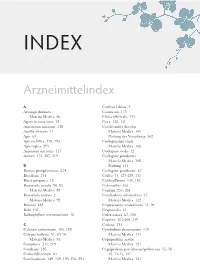

Arzneimittelindex

INDEX Arzneimittelindex A Cattleya labiata 2 Aerangis distincta Causticum 175 Materia Medica 86 China officinalis 225 Agaricus muscarius 52 Coca 128, 131 Americium nitricum 148 Cochleanthes discolor Anellia africana 11 Materia Medica 100 Apis 67 Prüfung der Verreibung 562 Apis mellifica 279, 293 Coeloglossum viride Apis regina 293 Materia Medica 106 Argentum nitricum 117 Coelogyne ovalis 12 Aurum 175, 207, 219 Coelogyne pandurata Materia Medica 108 B Prüfung 111 Barium phosphoricum 234 Coelogyne pandurate 67 Beryllium 244 Coffea 75, 127-128, 131 Bletia purpurea 12 Colibacillinum 159, 185 Brassavola acaulis 90, 93 Colocynthis 165 Materia Medica 88 Conium 253, 261 Brassavola nodosa 2 Corallorhiza odontorhiza 35 Materia Medica 92 Materia Medica 112 Bryonia 188 Cryptococcus neoformans 54, 90 Bufo 107 Cryptostylis 31 Bulbophyllum minutissimum 18 Culex musca 67, 190 Cuprum 207-208, 219 C Curium 134 Calcium carbonicum 105, 188 Cymbidium devonianum 119 Calypso bulbosa 57, 69, 96 Materia Medica 115 Materia Medica 94 Cypripedium acaule Camphora 211, 219 Materia Medica 121 Cantharis 185 Cypripedium parviflorum/pubescens 35, 38, Carbo fullerenum 63 45, 74-75, 127 Carcinosinum 149, 159, 199, 276, 293 Materia Medica 123 Klein_Orchideen_Deutsch_151108.indd 595 12.11.2015 11:00:33 596 Arzneimittelindex INDEX Cypripedium pubescens 280 Gymnadenia conopsea Cypripedium reginae Materia Medica 189 Materia Medica 132 H D Handystrahlung 75 Dactylorhiza fuchsii 50, 67, 139 Helleborus 234 Materia Medica 135 Herpes-Nosode 234 Dactylorhiza maculata 11, 55, 70, 136, 140 Holcoglossum amesianum 32 Materia Medica 138 Hyoscyamus 185, 188 Dactylorhiza praetermissa 43, 82, 141, 147 Materia Medica 143 I Dactylorhiza purpurella 143 Ipsea speciosa 6 Dendrobium lasianthera Materia Medica 160 K Dendrobium nobile 12 Kohlendioxid 274 Dendrobium tetragonum var. -

Redalyc.ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER?

Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology ISSN: 1409-3871 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica BACKHOUSE, GARY N. ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER? A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF THREATENED ORCHIDS IN AUSTRALIA Lankesteriana International Journal on Orchidology, vol. 7, núm. 1-2, marzo, 2007, pp. 28- 43 Universidad de Costa Rica Cartago, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44339813005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative LANKESTERIANA 7(1-2): 28-43. 2007. ARE OUR ORCHIDS SAFE DOWN UNDER? A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF THREATENED ORCHIDS IN AUSTRALIA GARY N. BACKHOUSE Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Division, Department of Sustainability and Environment 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Australia [email protected] KEY WORDS:threatened orchids Australia conservation status Introduction Many orchid species are included in this list. This paper examines the listing process for threatened Australia has about 1700 species of orchids, com- orchids in Australia, compares regional and national prising about 1300 named species in about 190 gen- lists of threatened orchids, and provides recommen- era, plus at least 400 undescribed species (Jones dations for improving the process of listing regionally 2006, pers. comm.). About 1400 species (82%) are and nationally threatened orchids. geophytes, almost all deciduous, seasonal species, while 300 species (18%) are evergreen epiphytes Methods and/or lithophytes. At least 95% of this orchid flora is endemic to Australia. -

ACT, Australian Capital Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

GLYDE POINT DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Notice of Intent

GLYDE POINT DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Notice of Intent Prepared for: DEPARTMENT OF INFRASTRUCTURE, PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENT GPO Box 1680 Darwin NT 0801 Prepared by: Kellogg Brown & Root Pty Ltd ABN 91 007 660 317 GPO Box 250 Darwin NT 0801 Telephone 8982 4500, Facsimile 8982 4550 16 December 2003 DE1008. 300-DO-002 Ó Kellogg Brown & Root Pty Ltd, 2004 Limitations Statement The sole purpose of this report and the associated services performed by Kellogg Brown & Root Pty Ltd (KBR) is to provide a Notice of Intent in accordance with the scope of services set out in t he contract between KBR and DIPE (‘the Client’). That scope of services was defined by the requests of the Client, by the time and budgetary constraints imposed by the Client, and by the availability of access to the site. KBR derived the data in this report primarily from examination of records in the public domain and interviews with individuals with information about the site. The passage of time, manifestation of latent conditions or impacts of future events may require further exploration at the site and subsequent data analysis, and re-evaluation of the findings, observations and conclusions expressed in this report. In preparing this report, KBR has relied upon and presumed accurate certain information (or absence thereof) relative to the site and the proposed development provided by government officials and authorities, the Client and others identified herein. Except as otherwise st ated in the report, KBR has not attempted to verify the accuracy or completeness of any such information. The findings, observations and conclusions expressed by KBR in this report are not, and should not be considered, an opinion concerning the significance of environmental impacts. -

Australian Orchidaceae: Genera and Species (12/1/2004)

AUSTRALIAN ORCHID NAME INDEX (21/1/2008) by Mark A. Clements Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research/Australian National Herbarium GPO Box 1600 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Corresponding author: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The Australian Orchid Name Index (AONI) provides the currently accepted scientific names, together with their synonyms, of all Australian orchids including those in external territories. The appropriate scientific name for each orchid taxon is based on data published in the scientific or historical literature, and/or from study of the relevant type specimens or illustrations and study of taxa as herbarium specimens, in the field or in the living state. Structure of the index: Genera and species are listed alphabetically. Accepted names for taxa are in bold, followed by the author(s), place and date of publication, details of the type(s), including where it is held and assessment of its status. The institution(s) where type specimen(s) are housed are recorded using the international codes for Herbaria (Appendix 1) as listed in Holmgren et al’s Index Herbariorum (1981) continuously updated, see [http://sciweb.nybg.org/science2/IndexHerbariorum.asp]. Citation of authors follows Brummit & Powell (1992) Authors of Plant Names; for book abbreviations, the standard is Taxonomic Literature, 2nd edn. (Stafleu & Cowan 1976-88; supplements, 1992-2000); and periodicals are abbreviated according to B-P- H/S (Bridson, 1992) [http://www.ipni.org/index.html]. Synonyms are provided with relevant information on place of publication and details of the type(s). They are indented and listed in chronological order under the accepted taxon name. Synonyms are also cross-referenced under genus. -

South East Flora

Regional Species Conservation Assessments DENR South East Region Complete Dataset for all Flora Assessments Dec 2011 In Alphabetical Order of Species Name MAP ID FAMILY NAME PLANT FORM NSX CODE SPECIES NAME COMMON NAME SOUTH EAST Regional EAST SOUTH Status Regional EAST SOUTH Status Score Regional Trend EAST SOUTH Score Regional EAST SOUTH Status+Trend Score SOUTH EAST Regional Trend EAST SOUTH FAMILY FAMILY NUMBER (CENSUS OF SA) EPBCACTSTATUSCODE NPWACTSTATUSCODE LASTOBSERVED_in_SE TOTAL_in_SA TOTAL_in_SE %_SOUTH_EAST_REGION EofO_in_SE_All_km2 EofO_in_SE_Recent_km2 AofO_in_SE_All_km2 AofO_in_SE_Recent_km2 711 91.182 LEGUMINOSAE legumes Y01536 Acacia acinacea Wreath Wattle 2009 814 60 7.37 3000 1700 48 27 LC 1 0 0.3 1.3 712 91.182 LEGUMINOSAE legumes K01545 Acacia brachybotrya Grey Mulga-bush 2001 563 18 3.20 800 500 16 9 RA 3 0 0.3 3.3 713 91.182 LEGUMINOSAE legumes M01554 Acacia continua Thorn Wattle 1974 836 1 0.12 100 1 VU 4 DD 0.0 4.0 714 91.182 LEGUMINOSAE legumes C05237 Acacia cupularis Cup Wattle 2002 577 83 14.38 4700 1500 65 20 LC 1 0 0.3 1.3 716 91.182 LEGUMINOSAE legumes K01561 Acacia dodonaeifolia Hop-bush Wattle R 2002 237 33 13.92 800 400 19 6 RA 3 0 0.3 3.3 718 91.182 LEGUMINOSAE legumes M01562 Acacia enterocarpa Jumping-jack Wattle EN E 2008 92 16 17.39 700 400 10 7 VU 4 0 0.3 4.3 719 91.182 LEGUMINOSAE legumes C05985 Acacia euthycarpa Wallowa 1992 681 7 1.03 500 100 7 1 RA 3 - 0.4 3.4 720 91.182 LEGUMINOSAE legumes S01565 Acacia farinosa Mealy Wattle 1997 325 88 27.08 4000 1600 65 23 NT 2 0 0.3 2.3 721 91.182 LEGUMINOSAE -

NORTH SHORE GROUP Ku-Ring-Gai Wildflower Garden

Australian Plants Society NORTH SHORE GROUP Ku-ring-gai Wildflower Garden Topic 22: ORCHIDS (Orchidaceae) Did you know that, The orchid family is the largest and most successful in the world. Theophrastus used the name Orchis (Greek meaning testicle) about 300BC to describe the orchid family. He thought the plant’s underground tubers bore a resemblance to testicles. Linnaeus later used the name Orchis to describe this plant genus. Orchids are loved by people. Unscrupulous collectors have removed extensive numbers of orchids from the wild, to the extent that in many areas orchids are no longer found. The Orchid Family The orchid family, Orchidaceae, has about 25000 species in about 1000 genera. Australia is not as rich in orchids as other countries, but close to 200 genera with about 1300 species are found here. Three quarters are terrestrial and the others are epiphytes. Flower Structure Orchids are herbs with distinctive floral features. They are monocotyledons with three sepals and three petals, but one of the petals in most species is greatly modified to form the labellum or tongue. Thelymitra aristata Diuris longifolia The labellum’s primary function is to attract pollinators. It is usually larger than the other segments and can be entire or with 3 lobes. It can be fixed or attached by a flexible strap 1 which snaps shut and traps an insect to achieve pollination. It commonly has a variety of structure, plates, calli, hairs and glands. The male and female sexual parts are combined to form the fleshy structure called the column, located centrally in the flower. -

Biodiversity Summary: Wimmera, Victoria

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations.