DOCTORAL THESIS - Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plan De Şcolarizare Clasa Pregătitoare an Şcolar 2019-2020

Plan de şcolarizare Clasa pregătitoare An şcolar 2019-2020 Masă / Normal / Step by Step / Buget / Limba română Număr clase Nr. crt. Denumire unitate Localitate Localitate superioară Capacitate (locuri) aprobate 1 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA NR 4 MEDIAS MEDIAŞ MUNICIPIUL MEDIAŞ 1 25 Total Masă / Normal / Step by Step / Buget / Limba română 1 25 Pagina 1 / 16 Masă / Normal / Tradițional / Buget / Limba germană Număr clase Nr. crt. Denumire unitate Localitate Localitate superioară Capacitate (locuri) aprobate 1 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA "HERMAN OBERTH" MEDIAS MEDIAŞ MUNICIPIUL MEDIAŞ 3 75 2 COLEGIUL NATIONAL "O.GOGA" SIBIU SIBIU MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 1 25 3 COLEGIUL NATIONAL PEDAGOGIC "A.SAGUNA" SIBIU SIBIU MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 1 25 4 LICEUL TEORETIC "ONISIFOR GHIBU" SIBIU SIBIU MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 1 25 5 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA "I.L.CARAGIALE" SIBIU SIBIU MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 1 25 6 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA "NICOLAE IORGA" SIBIU SIBIU MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 2 50 7 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA NR 18 SIBIU SIBIU MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 1 25 8 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA NR 2 SIBIU SIBIU MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 2 50 9 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA NR 4 SIBIU SIBIU MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 1 25 10 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA "GEORG DANIEL TEUTSCH" AGNITA AGNITA ORAŞ AGNITA 1 25 11 LICEUL TEORETIC "GUSTAV GUNDISCH" CISNADIE CISNĂDIE ORAŞ CISNĂDIE 1 25 Total Masă / Normal / Tradițional / Buget / Limba germană 15 375 Pagina 2 / 16 Masă / Normal / Tradițional / Buget / Limba maghiară Număr clase Nr. crt. Denumire unitate Localitate Localitate superioară Capacitate (locuri) aprobate 1 SCOALA GIMNAZIALA "BATHORY ISTVAN" MEDIAS MEDIAŞ MUNICIPIUL MEDIAŞ 1 14 Total -

1/49 Proces-Verbal Din Data 24.05.2016 SULYLQG GHVHPQDUHD Suhúhglqġloru ELURXULORU HOHFWRUDOH DOH VHFĠLLORU GH YRWDUH Constit

39DILúDUHMXGHĠ Proces-verbal din data 24.05.2016SULYLQGGHVHPQDUHDSUHúHGLQĠLORUELURXULORUHOHFWRUDOHDOHVHFĠLLORUGHYRWDUH constituite pentru alegerile locale din anul 2016úLDORFĠLLWRULORUDFHVWRUD &LUFXPVFULSĠLD(OHFWRUDOă-XGHĠHDQăQU34, SIBIU ,QL܊LDOD Nr. crt. UAT 1U6HF܊LH ,QVWLWX܊LD )XQF܊LD Nume Prenume $GUHVă WDWăOXL ùFRDODJLPQD]LDOăQU 1 MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 1 FXVWUXFWXUD*UDGLQLĠDFX 3UH܈HGLQWH +$ù8 MARIANA I SIBIU, MUNICIPIUL SIBIU program prelungit nr. 20 ùFRDODJLPQD]LDOăQU 2 MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 1 FXVWUXFWXUD*UDGLQLĠDFX /RF܊LLWRU BRATU CORNELIU-ADRIAN C SIBIU, MUNICIPIUL SIBIU program prelungit nr. 20 ùFRDODJLPQD]LDOăQU 3 MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 2 FXVWUXFWXUD*UDGLQLĠDFX 3UH܈HGLQWH GROVU GABRIELA-ANA N SIBIU, MUNICIPIUL SIBIU program prelungit nr. 20 ùFRDODJLPQD]LDOăQU 4 MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 2 FXVWUXFWXUD*UDGLQLĠDFX /RF܊LLWRU GANEA DELIA ELENA ù SIBIU, MUNICIPIUL SIBIU program prelungit nr. 20 5 MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 3 ùFRDODJLPQD]LDOăQU 3UH܈HGLQWH TROANCA DANIEL FLORIN I SIBIU, MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 6 MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 3 ùFRDODJLPQD]LDOăQU /RF܊LLWRU 1($0ğ8 SANDRA-IOANA D SIBIU, MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 7 MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 4 ùFRDODJLPQD]LDOăQU 3UH܈HGLQWH RUSU ANDREA D SIBIU, MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 8 MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 4 ùFRDODJLPQD]LDOăQU /RF܊LLWRU 6&Ă5,ù25($18 MARIAN-VALERIU C SIBIU, MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 9 MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 5 ùFRDODJLPQD]LDOăQU 3UH܈HGLQWH KETNEY OTTO V SIBIU, MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 10 MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 5 ùFRDODJLPQD]LDOăQU /RF܊LLWRU 'Ă1&Ă1(ğ MARIA-MONICA V SIBIU, MUNICIPIUL SIBIU ùFRDODJLPQD]LDOăQU 11 MUNICIPIUL SIBIU 6 FXVWUXFWXUDùFRDOD 3UH܈HGLQWH )5Ă7,&, ADINA-MARIANA I SIBIU, -

Județul Sibiu RAPORT DE PROGRES

Instituția Prefectului – Județul Sibiu Compartiment Minorități Tel: 0269 210 104 Strada Andrei Șaguna nr.10 Fax: 0269 218 177 Sibiu, 550009 https://sb.prefectura.mai.gov.ro Nr. 4.878/30.03.2020 APROB, PREFECT MIRCEA-DORIN CREȚU RAPORT DE PROGRES privind implementarea Planului Județean de Măsuri de incluziune a cetățenilor români aparținând minorității rome în anul 2019 INTRODUCERE. ACTIVITATEA BIROULUI JUDEȚEAN PENTRU ROMI Activitatea desfășurată în anul 2019 s-a raportat la Planul de Măsuri al Județului Sibiu pentru incluziunea cetățenilor români aparținând minorități rome elaborat în conformitate cu prevederile Strategiei Guvernului României de incluziune a cetățenilor români aparținând minorității rome pentru perioada 2015-2020, aprobată prin Hotărârea Guvernului nr. 18/2015, publicată în Monitorul Oficial al României, Partea I, nr. 49 din 21 ianuarie 2015. Obiectivele urmărite au fost legate de asigurarea incluziunii socio-economice și culturale a cetățenilor români aparținând minorității rome prin implementarea unor politici integrate în domeniul sănătății, educației, ocupării forței de muncă, locuirii, culturii, infrastructurii sociale și ordinii publice, urmărind Planul Județean de Măsuri, elaborat în anul 2015, cu ultima completare și actualizare prin documentul nr. 3.088 /26.02.2018, aprobat în ședința Grupului Județean de Lucru Mixt pentru Romi din 01.03.2018. În cadrul ședințelor Grupului Județean de Lucru Mixt pentru Romi, au fost dezbătute tematici axate pe protejarea drepturilor și libertăților fundamentale, urmărindu-se asigurarea pentru cetățenii romi a diverselor tipuri de servicii necesare, dar și realizarea unui cadru cât mai flexibil de dialog, deschis tuturor actorilor implicați: instituții ale statului, unitățile administrativ-teritoriale din județul Sibiu, servicii Pagina 1 / 47 publice comunitare, reprezentanți ai societății civile, membri titulari ai grupului de lucru. -

Lista Ratelor De Incidență Covid-19 Pe Localități

Lista ratelor de incidență pe localități (actualizare: 27 mai), comunicată de CNCCI (Centrul Național de Conducere și Coordonare a Intervenției) Nr. crt. Județ Localitate Incidență 1 ARAD ŞIŞTAROVĂŢ 10,36 2 TULCEA CARCALIU 9,68 3 ALBA ROŞIA DE SECAŞ 8,05 4 CARAŞ-SEVERIN CĂRBUNARI 5,74 5 ALBA CERGĂU 5,51 6 ARGEŞ CEPARI 5,43 7 CARAŞ-SEVERIN GORUIA 5,2 8 COVASNA BIXAD 4,68 9 TELEORMAN SĂCENI 4,66 10 ALBA GÂRDA DE SUS 4,62 11 CLUJ PETREŞTII DE JOS 4,26 12 TIMIŞ FÂRDEA 4,1 13 SĂLAJ MESEŞENII DE JOS 4,01 14 VÂLCEA ŞTEFĂNEŞTI 3,93 15 COVASNA MERENI 3,92 16 TIMIŞ NĂDRAG 3,91 17 TELEORMAN PLOPII-SLĂVITEŞTI 3,86 18 ARGEŞ NUCŞOARA 3,71 19 BIHOR COPĂCEL 3,64 20 VÂLCEA GLĂVILE 3,49 21 BIHOR ORAŞ VAŞCĂU 3,36 22 BISTRIŢA-NĂSĂUD POIANA ILVEI 3,35 23 TELEORMAN DRĂGĂNEŞTI DE VEDE 3,33 24 ALBA OHABA 3,13 25 VASLUI COROIEŞTI 3,11 26 ALBA CÂLNIC 2,99 27 CĂLĂRAŞI VALEA ARGOVEI 2,98 28 OLT MILCOV 2,97 29 NEAMŢ TARCĂU 2,96 30 IALOMIŢA MOLDOVENI 2,95 31 MUREŞ STÂNCENI 2,83 32 BISTRIŢA-NĂSĂUD URMENIŞ 2,79 33 NEAMŢ PĂSTRĂVENI 2,78 34 HUNEDOARA CÂRJIŢI 2,72 35 PRAHOVA CHIOJDEANCA 2,61 36 IAŞI CIOHORĂNI 2,58 37 TIMIŞ MORAVIŢA 2,54 38 ARGEŞ VULTUREŞTI 2,52 39 ALBA ORAŞ ABRUD 2,49 40 HARGHITA ORAŞ BĂILE TUŞNAD 2,49 41 TULCEA ORAŞ MĂCIN 2,48 42 PRAHOVA PLOPU 2,47 43 BUZĂU MOVILA BANULUI 2,45 44 BUZĂU MURGEŞTI 2,42 45 TIMIŞ VOITEG 2,42 46 CARAŞ-SEVERIN FOROTIC 2,4 47 VÂLCEA ORAŞ BĂBENI 2,4 48 SATU MARE SUPUR 2,4 49 VÂLCEA CREŢENI 2,39 50 CARAŞ-SEVERIN RĂCĂŞDIA 2,38 51 CARAŞ-SEVERIN CICLOVA ROMÂNĂ 2,37 52 NEAMŢ TAŞCA 2,33 53 SUCEAVA FÂNTÂNA MARE 2,32 54 TIMIŞ FIBIŞ 2,3 -

Colecţia Registre De Stare Civilă (1607-1950)

MINISTERUL ADMINISTRAŢIEI ŞI INTERNELOR ARHIVELE NAŢIONALE SERVICIUL JUDEŢEAN SIBIU Colecţia Registre de Stare Civilă INV.Nr. 378 I N V E N T A R Anii: 1607-1950 SJAN Sibiu Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei PREFAŢĂ Prezentul inventar conţine: Colecţia Registre de Stare Civilă, anii extremi 1607-1950. Întreaga cantitate a fost structurată în funcţie de specificul documentelor după cum urmează: registre de stare civilă ordonate alfabetic în funcţie de localităţile la care fac referire (181 la număr), în cadrul acestora pe confesiuni, iar în cadrul fiecărei confesiuni cronologic. Registrele sunt scrise în limbile: germană, maghiară, latină, română ( cu alfabet chirilic şi latin) şi aparţin confesiunilor ortodoxă, evanghelică, mozaică, reformată, greco - catolică, romano - catolică ( botezaţi, căsătoriţi, morţi). Registrele cuprinse în colecţie au fost întocmite la început de către parohii, prin preoţii locali sub forma matricolelor confesionale, cu scopul de a inregistra evenimentele considerate fundamentale în viaţa comunităţii respectiv: ( botezul, căsătoria, moartea) şi probabil de control administrativ- religios al acestora. De la 1 octombrie 1895 s-au introdus (în baza unei legi din 18 decembrie 1894) în Transilvania registrele de stare civilă a căror completarea cădea în sarcina funcţionarilor publici şi nu a preoţilor. Printr-o modificare a legii în 1904 s-a stabilit ca la nivel de comună sediul notarului să coincidă cu sediul Oficiului Cercual de Stare civilă, notarilor conferindu-li-seSJAN atribu Sibiuţii în domeniul stării civile. Prevederile acestea au rămas în vigoare şi după 1918 până la adoptarea Legii pentru unificarea şi organizarea actelor de stare civilă. Colecţia mai cuprinde Registre de naţionalitate (1924 - 1951) ordonate alfabetic, scrise în limba română şi Registre statistice de stare civilă Arhiveledin anul 1851, ordonate Nationale alfabetic pe localit ăţalei, scrise înRomaniei română (cu alfabet chirilic), germană şi maghiară. -

Hotărârea Nr. 73/2020 a Comitetului Județean Pentru Situații De Urgență Sibiu

Hotărârea nr. 73/2020 a Comitetului Județean pentru Situații de Urgență Sibiu Art. 1 (1) În conformitate cu prevederile art. 3, alin. (2) din Anexa 2 la H.G. 856/2020, pentru o perioada de 14 zile, începând cu data de 03.11.2020, ora 00:00 până la data de 16.11.2020, ora 24:00, se va institui obligativitatea purtării măştii de protecţie, astfel încât să acopere nasul şi gura, pentru toate persoanele care au împlinit vârsta de 5 ani, prezente în toate spaţiile publice deschise, pe întreg teritoriul judeţului Sibiu. * Se vor excepta de la această măsură copiii cu vârsta mai mică de 5 ani. (2) În conformitate cu prevederile art. 3, alin. (3) din Anexa 2 la H.G. 856/2020, pentru o perioada de 14 zile, începând cu data de 03.11.2020, ora 00:00 până la data de 16.11.2020, ora 24:00, pe teritoriul UAT Apoldu de Jos (Sat Apoldu de Jos),UAT Porumbacu de Jos (Sat Colun), UAT Loamneş (Sat Haşag), UAT Gura Râului (Sat Gura Râului ), UAT Şura Mare (Sat Şura Mare), UAT Boiţa (Sat Boiţa), UAT Şeica Mică (Sat Soroştin), UAT Biertan (Sat Biertan, Sat Copşa Mare), UAT Axente Sever (Sat Agârbiciu), UAT Dumbrăveni (Oraş Dumbrăveni), UAT Roşia (Sat Daia, Sat Caşolţ ),UAT Bârghiş (Sat Ighişu Vechi, Bârghiş), UAT Avrig (Sat Mârşa), UAT Cârţişoara (Sat Cârţişoara), UAT Ludoş (Sat Gusu), UAT Nocrich (Sat Nocrich), UAT Sălişte (Oraş Sălişte), UAT Alţâna (Sat Beneşti), UAT Racoviţa (Sat Racoviţa) şi UAT Păuca (Sat Presaca), administratorii/proprietarii spaţiilor publice deschise afişează la loc vizibil informaţii privind obligativitatea purtării măştii de protecţie în spaţiile respective. -

More Than Churches an Approach to Develop Strategies for the Economical Future of the Villages of Transylvania

More than churches An approach to develop strategies for the economical future of the villages of Transylvania Lukas Valentin Flandorfer 01126310 Kleines Entwerfen Schönberg 2018S More than churches An approach to develop strategies for the economical future of th villages of Transylvania Lukas Valentin Flandorfer Vienna University of Technology, Department of Architecture [email protected] Keywords: agriculture, traditional farming, economy, fortifed church, landscape, wildlife 1. Preamble When I started thinking about the project, Romania, Transylvania and the Saxon villages I had the idea that food could be the key to boost tourism, economy and living standard in the villages. It should be a program or a programmatic intervention which connects all the villages in some way. I thought all these villages are probably very similar to each other and only covering the area with one big idea would attract enough people to achieve a good performance. But after all the experiences I had in the region, in the villages, with the people and the more I thought about them, my conclusion shifted from accentuating the similiarites to developing the differencies. Maybe the villages are similar, but the strategic focus should switch from the similiarites (fortified churches) to differencies, which do not even have to be very distinct already. There are so many possibilities originating from cultural traditions, landscape, handcrafts and so on. The goal has to be to create a network of possibilities, generated from the uniQueness of each single village while avoiding separation. Also I want to note that this possibilities do not have to focus on tourism exclusively, but rather be strategies to strengthen the economy and quality of life in the villages. -

Modelarea Dispersiei Poluanților Atmosferici

CONSILIUL JUDEȚEAN SIBIU Plan de menținere a calității aerului în județul Sibiu (Draft) ANEXA MODELAREA DISPERSIEI POLUANȚILOR ATMOSFERICI ANEXĂ LA PLANUL DE MENȚINERE A CALITĂȚII AERULUI ÎN JUDEȚUL SIBIU 2016 - 2020 CONSILIUL JUDEȚEAN SIBIU Mai 2018 1 CONSILIUL JUDEȚEAN SIBIU Plan de menținere a calității aerului în județul Sibiu (Draft) MODELAREA DISPERSIEI POLUANȚILOR ATMOSFERICI Pentru modelarea dispersiei poluanților atmosferici din județul Sibiu, s-a utilizat programul BREEZE AERMOD/ISCPro, un model de dispersie gaussian, furnizat de BREEZE USA și care este utilizat de US EPA. Conform furnizorului de soft, BREEZE AERMOD/ISC oferă cel mai complet sistem de modelare a calității aerului disponibil. Programul este proiectat pentru a estima concentrațiile de poluanți și depunerile din surse industriale complexe. Programul permite estimarea concentrațiilor din aproape orice tip de sursă care emite poluanți nereactivi, de tipul: surse punctuale (fixe), din surse liniare (trafic), din surse difuze/de suprafată etc. Modelul BREEZE AERMOD/ISC Pro În program sunt incluse mai multe opţiuni pentru modelarea impactului surselor de poluare asupra calităţii aerului. Pentru rularea modelului sunt necesare două tipuri de fişiere ce conţin datele meteorologice, unul cu date de suprafaţă şi unul cu date privind profilurile pe verticală, ambele au fost achiziționate direct, prelucrate de echipe de meteorologi afiliate furnizorului softului BREEZE, date specifice pentru județul Sibiu. Date de intrare în soft-ul de dispersie (obligatorii, recomandate și opționale): Date referitoare la poluant: tipul poluantului, timpul de mediere a concentraţiilor (ore, lună, ani, perioadă) etc. Date referitoare la teren: tipul terenului (plat/înclinat), înălţimea terenului (introducând datele topografice specifice amplasamentului surselor de emisie şi receptorilor, astfel că se pot efectua simulări pentru situaţiile întâlnite în terenurile reale). -

Jud. Sibiu Incidenta Localitati 11.02.2021

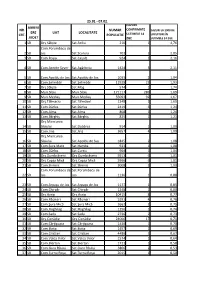

29.01 - 11.02. CAZURI ABREVI NR. NUMAR CONFIRMATE CAZURI LA 1000 DE ERE UAT LOCALITATE CRT. POPULATIE ULTIMELE 14 LOCUITORI ÎN JUDET ZILE ULTIMELE 14 ZILE 1 SB Com.Şeica Mare Sat.Ştenea 160 1 6,25 2 SB Com.Mihăileni Sat.Mihăileni 201 1 4,98 3 SB Orş.Sălişte Sat.Aciliu 210 1 4,76 4 SB Com.Bârghiş Sat.Pelişor 506 2 3,95 5 SB Orş.Tălmaciu Sat.Colonia Tălmaciu 294 1 3,40 6 SB Com.Roşia Sat.Caşolţ 924 3 3,25 7 SB Com.Dârlos Sat.Curciu 964 3 3,11 8 SB Com.Şelimbăr Sat.Şelimbăr 11928 34 2,85 9 SB Orş.Tălmaciu Sat.Tălmăcel 1248 3 2,40 10 SB Com.Axente Sever Sat.Agârbiciu 1424 3 2,11 11 SB Mun.Mediaş Mun.Mediaş 55093 112 2,03 12 SB Com.Valea Viilor Sat.Valea Viilor 1574 3 1,91 13 SB Com.Şura Mică Sat.Şura Mică 2662 5 1,88 14 SB Mun.Sibiu Mun.Sibiu 171117 310 1,81 15 SB Com.Cristian Sat.Cristian 4486 8 1,78 Com.Porumbacu de Sat.Porumbacu de 16 SB Jos Jos 1136 2 1,76 17 SB Com.Sadu Sat.Sadu 2736 4 1,46 Com.Porumbacu de 18 SB Jos Sat.Scoreiu 701 1 1,43 19 SB Com.Slimnic Sat.Slimnic 3008 4 1,33 20 SB Com.Bârghiş Sat.Bârghiş 825 1 1,21 Com.Porumbacu de Sat.Porumbacu de 21 SB Jos Sus 903 1 1,11 Orş.Miercurea 22 SB Sibiului Sat.Dobârca 914 1 1,09 23 SB Com.Jina Sat.Jina 3657 4 1,09 Orş.Miercurea 24 SB Sibiului Sat.Apoldu de Sus 1845 2 1,08 25 SB Com.Şura Mare Sat.Hamba 923 1 1,08 26 SB Com.Hoghilag Sat.Valchid 926 1 1,08 27 SB Orş.Copşa Mică Orş.Copşa Mică 5966 6 1,01 28 SB Com.Turnu Roşu Sat.Turnu Roşu 2015 2 0,99 29 SB Com.Apoldu de Jos Sat.Apoldu de Jos 1033 1 0,97 30 SB Orş.Sălişte Orş.Sălişte 3116 3 0,96 31 SB Com.Răşinari Sat.Răşinari 5291 5 0,95 -

Jud. Sibiu Incidenta Localitati 27.02.2021

14.02 - 27.02.2021 CAZURI ABREVI NR. NUMAR CONFIRMATE CAZURI LA 1000 DE ERE UAT LOCALITATE CRT. POPULATIE ULTIMELE 14 LOCUITORI ÎN JUDET ZILE ULTIMELE 14 ZILE 1 SB Com.Roşia Sat.Nucet 54 1 18.52 2 SB Com.Alţina Sat.Beneşti 306 4 13.07 Com.Porumbacu de 3 SB Jos Sat.Scoreiu 701 8 11.41 4 SB Orş.Sălişte Sat.Vale 399 4 10.03 5 SB Orş.Sălişte Sat.Galeş 351 3 8.55 Orş.Miercurea 6 SB Sibiului Sat.Apoldu de Sus 1845 15 8.13 7 SB Orş.Sălişte Orş.Sălişte 3116 15 4.81 8 SB Com.Orlat Sat.Orlat 3364 16 4.76 9 SB Com.Bazna Sat.Boian 1589 7 4.41 10 SB Com.Apoldu de Jos Sat.Apoldu de Jos 1033 4 3.87 11 SB Com.Sadu Sat.Sadu 2736 8 2.92 12 SB Com.Şelimbăr Sat.Şelimbăr 11928 34 2.85 13 SB Mun.Sibiu Mun.Sibiu 171117 478 2.79 14 SB Com.Şeica Mare Sat.Boarta 381 1 2.62 15 SB Com.Roşia Sat.Roşia 1757 4 2.28 16 SB Com.Cristian Sat.Cristian 4486 10 2.23 Com.Porumbacu de Sat.Porumbacu de 17 SB Jos Sus 903 2 2.21 18 SB Com.Dârlos Sat.Curciu 964 2 2.07 19 SB Com.Şeica Mare Sat.Şeica Mare 3443 7 2.03 20 SB Com.Şura Mare Sat.Şura Mare 4172 8 1.92 21 SB Com.Biertan Sat.Copşa Mare 528 1 1.89 22 SB Orş.Cisnădie Orş.Cisnădie 24006 45 1.87 23 SB Com.Iacobeni Sat.Stejărişu 536 1 1.87 24 SB Orş.Sălişte Sat.Săcel 566 1 1.77 25 SB Orş.Avrig Sat.Bradu 1151 2 1.74 26 SB Com.Arpaşu de Jos Sat.Arpaşu de Jos 1177 2 1.70 27 SB Mun.Mediaş Mun.Mediaş 55093 88 1.60 28 SB Orş.Copşa Mică Orş.Copşa Mică 5966 9 1.51 29 SB Com.Şura Mică Sat.Şura Mică 2662 4 1.50 30 SB Com.Axente Sever Sat.Agârbiciu 1424 2 1.40 Orş.Miercurea Orş.Miercurea 31 SB Sibiului Sibiului 2149 3 1.40 32 SB Com.Loamneş -

NR. CRT. ABREVI ERE JUDET UAT LOCALITATE NUMAR POPULATIE 1 SB Com.Alţina Sat.Beneşti 306 4 13.07 2 SB Orş.Sălişte Sat.Vale

18.02 - 03.03.2021 CAZURI ABREVI NR. NUMAR CONFIRMATE CAZURI LA 1000 DE ERE UAT LOCALITATE CRT. POPULATIE ULTIMELE 14 LOCUITORI ÎN JUDET ZILE ULTIMELE 14 ZILE 1 SB Com.Alţina Sat.Beneşti 306 4 13.07 2 SB Orş.Sălişte Sat.Vale 399 5 12.53 Com.Porumbacu de 3 SB Jos Sat.Scoreiu 701 7 9.99 4 SB Orş.Sălişte Sat.Galeş 351 3 8.55 Orş.Miercurea 5 SB Sibiului Sat.Apoldu de Sus 1845 12 6.50 6 SB Com.Arpaşu de Jos Sat.Nou Român 378 2 5.29 7 SB Orş.Sălişte Orş.Sălişte 3116 16 5.13 8 SB Com.Bazna Sat.Boian 1589 6 3.78 9 SB Com.Sadu Sat.Sadu 2736 10 3.65 10 SB Com.Orlat Sat.Orlat 3364 12 3.57 11 SB Com.Alma Sat.Şmig 867 3 3.46 12 SB Com.Aţel Sat.Aţel 1474 5 3.39 Com.Porumbacu de Sat.Porumbacu de 13 SB Jos Sus 903 3 3.32 14 SB Com.Şura Mare Sat.Şura Mare 4172 13 3.12 15 SB Mun.Sibiu Mun.Sibiu 171117 495 2.89 16 SB Com.Şelimbăr Sat.Şelimbăr 11928 34 2.85 17 SB Com.Roşia Sat.Roşia 1757 5 2.85 Com.Porumbacu de 18 SB Jos Sat.Sărata 380 1 2.63 19 SB Com.Şeica Mare Sat.Boarta 381 1 2.62 Orş.Miercurea Orş.Miercurea 20 SB Sibiului Sibiului 2149 5 2.33 21 SB Com.Cristian Sat.Cristian 4486 10 2.23 22 SB Orş.Copşa Mică Orş.Copşa Mică 5966 13 2.18 23 SB Orş.Cisnădie Orş.Cisnădie 24006 47 1.96 24 SB Com.Roşia Sat.Daia 1043 2 1.92 25 SB Com.Răşinari Sat.Răşinari 5291 10 1.89 26 SB Com.Racoviţa Sat.Racoviţa 2183 4 1.83 27 SB Com.Turnu Roşu Sat.Sebeşu de Jos 550 1 1.82 28 SB Orş.Sălişte Sat.Săcel 566 1 1.77 29 SB Mun.Mediaş Sat.Ighişu Nou 1730 3 1.73 30 SB Com.Arpaşu de Jos Sat.Arpaşu de Jos 1177 2 1.70 31 SB Com.Loamneş Sat.Loamneş 601 1 1.66 32 SB Com.Cârţa Sat.Cârţa -

Incidenta Pe Localitati 07.02.2021

25.01 - 07.02. CAZURI ABREVI NR. NUMAR CONFIRMATE CAZURI LA 1000 DE ERE UAT LOCALITATE CRT. POPULATIE ULTIMELE 14 LOCUITORI ÎN JUDET ZILE ULTIMELE 14 ZILE 1 SB Orş.Sălişte Sat.Aciliu 210 1 4,76 Com.Porumbacu de 2 SB Jos Sat.Scoreiu 701 2 2,85 3 SB Com.Roşia Sat.Caşolţ 924 2 2,16 4 SB Com.Axente Sever Sat.Agârbiciu 1424 3 2,11 5 SB Com.Apoldu de Jos Sat.Apoldu de Jos 1033 2 1,94 6 SB Com.Şelimbăr Sat.Şelimbăr 11928 23 1,93 7 SB Orş.Sălişte Sat.Mag 574 1 1,74 8 SB Mun.Sibiu Mun.Sibiu 171117 289 1,69 9 SB Mun.Mediaş Mun.Mediaş 55093 92 1,67 10 SB Orş.Tălmaciu Sat.Tălmăcel 1248 2 1,60 11 SB Com.Dârlos Sat.Dârlos 2419 3 1,24 12 SB Com.Alma Sat.Alma 808 1 1,24 13 SB Com.Bârghiş Sat.Bârghiş 825 1 1,21 Orş.Miercurea 14 SB Sibiului Sat.Dobârca 914 1 1,09 15 SB Com.Jina Sat.Jina 3657 4 1,09 Orş.Miercurea 16 SB Sibiului Sat.Apoldu de Sus 1845 2 1,08 17 SB Com.Şura Mare Sat.Hamba 923 1 1,08 18 SB Com.Dârlos Sat.Curciu 964 1 1,04 19 SB Orş.Dumbrăveni Orş.Dumbrăveni 5913 6 1,01 20 SB Orş.Copşa Mică Orş.Copşa Mică 5966 6 1,01 21 SB Com.Slimnic Sat.Slimnic 3008 3 1,00 Com.Porumbacu de Sat.Porumbacu de 22 SB Jos Jos 1136 1 0,88 23 SB Com.Arpaşu de Jos Sat.Arpaşu de Jos 1177 1 0,85 24 SB Com.Chirpăr Sat.Chirpăr 1248 1 0,80 25 SB Orş.Avrig Orş.Avrig 10415 8 0,77 26 SB Com.Răşinari Sat.Răşinari 5291 4 0,76 27 SB Com.Şura Mică Sat.Şura Mică 2662 2 0,75 28 SB Com.Hoghilag Sat.Hoghilag 1356 1 0,74 29 SB Com.Sadu Sat.Sadu 2736 2 0,73 30 SB Orş.Cisnădie Orş.Cisnădie 24006 17 0,71 31 SB Com.Cârţişoara Sat.Cârţişoara 1436 1 0,70 32 SB Com.Boiţa Sat.Boiţa 1457 1