Economic Voting and the Great Recession in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Elections

2003 PILK PEEGLISSE • GLANCE AT THE MIRROR Riigikogu valimised Parliamentary Elections 2. märtsil 2003 toimusid Eestis Riigikogu On 2 March 2003, Parliamentary elections took valimised.Valimisnimekirjadesse kanti 963 place in Estonia. The election list contained 963 kandidaati, kellest 947 kandideeris 11 erineva candidates from eleven different parties and 16 partei nimekirjas, lisaks proovis Riigikogusse independent candidates. 58.2% of eligible voters pääseda 16 üksikkandidaati. Hääletamas käis went to the polls. The Estonian Centre Party 58,2% hääleõiguslikest kodanikest. Enim hääli gained the most support of voters with 25.4% of kogus Eesti Keskerakond – 25,4%.Valimistel total votes. Res Publica – A Union for the Republic esmakordselt osalenud erakond Ühendus – who participated in the elections for the first Vabariigi Eest - Res Publica sai 24,6% häältest. time, gathered 24.6% of total votes. The parties Riigikogusse pääsesid veel Eesti Reformi- that obtained seats in the parliament were the Estonian Reform Party (17.7%), the Estonian erakond – 17,7%, Eestimaa Rahvaliit – 13,0%, People's Union (13.0%), the Pro Patria Union Isamaaliit – 7,3% ja Rahvaerakond Mõõdukad – (7.3%) and the People's Party Mõõdukad (7.0%). 7,0% Valitsuse moodustasid Res Publica, Eesti The Cabinet was formed by Res Publica, the Reformierakond ja Eestimaa Rahvaliit. Estonian Reform Party and the Estonian People's Peaministriks nimetati Res Publica esimees Union. The position of the Prime Minister went to Juhan Parts.Valitsus astus ametisse 10. aprillil Juhan Parts, chairman of Res Publica. The Cabinet 2003 ametivande andmisega Riigikogu ees. was sworn in on 10 April 2003. VALI KORD! CHOOSE ORDER! Res Publica sööst raketina Eesti poliitika- Res Publica's rocketing to the top of Estonian politics taevasse sai võimalikuks seetõttu, et suur osa was made possible by a great number of voters hääletajatest otsib üha uusi, endisest usaldus- looking for new, more reliable faces. -

Appendix 1A: List of Government Parties September 12, 2016

Updating the Party Government data set‡ Public Release Version 2.0 Appendix 1a: List of Government Parties September 12, 2016 Katsunori Seki§ Laron K. Williams¶ ‡If you use this data set, please cite: Seki, Katsunori and Laron K. Williams. 2014. “Updating the Party Government Data Set.” Electoral Studies. 34: 270–279. §Collaborative Research Center SFB 884, University of Mannheim; [email protected] ¶Department of Political Science, University of Missouri; [email protected] List of Government Parties Notes: This appendix presents the list of government parties that appear in “Data Set 1: Governments.” Since the purpose of this appendix is to list parties that were in government, no information is provided for parties that have never been in government in our sample (i.e, opposition parties). This is an updated and revised list of government parties and their ideological position that were first provided by WKB (2011). Therefore, countries that did not appear in WKB (2011) have no list of government parties in this update. Those countries include Bangladesh, Botswana, Czechoslovakia, Guyana, Jamaica, Namibia, Pakistan, South Africa, and Sri Lanka. For some countries in which new parties are frequently formed and/or political parties are frequently dissolved, we noted the year (and month) in which a political party was established. Note that this was done in order to facilitate our data collection, and therefore that information is not comprehensive. 2 Australia List of Governing Parties Australian Labor Party ALP Country Party -

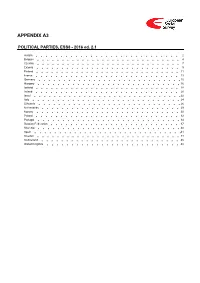

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Estonia Country Report BTI 2014

BTI 2014 | Estonia Country Report Status Index 1-10 9.42 # 3 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 9.70 # 2 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 9.14 # 3 of 129 Management Index 1-10 7.26 # 4 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2014. It covers the period from 31 January 2011 to 31 January 2013. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014 — Estonia Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2014 | Estonia 2 Key Indicators Population M 1.3 HDI 0.846 GDP p.c. $ 23064.8 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.0 HDI rank of 187 33 Gini Index 36.0 Life expectancy years 76.1 UN Education Index 0.919 Poverty3 % 1.5 Urban population % 69.6 Gender inequality2 0.158 Aid per capita $ - Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2013. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary Estonia has made an overall impressive recovery from the sharp economic downturn in 2009/2010. The recovery has been aided by innovative and highly efficient public and private sectors. The country has retained its attractiveness to foreign investors thanks to its openness, streamlined government, strong rule of law and business-friendly economic environment. -

National Government Versus Ethnic Minority: Ethnopolitics and Party Systems in New Europe

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Waseda University National Government versus Ethnic Minority: Ethnopolitics and Party Systems in New Europe A Dissertation by Ryo NAKAI Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Political Science at Graduate School of Political Science Waseda University (September 2012) ii Contents Page Abbrebiations of Political Parties’ Name iv Acknowledgement vi Chapter 1. Introduction 1 Part I Theory and Statistics Chapter 2. Theories: Ethnopolitics is About Interests 13 Chapter 3. Statistics: The Effect of Party System on Ethnopolitics 27 Part II Case Studies Chapter 4. The Baltic States as a Wonderland 46 Chapter 5. Latvia: Confrontational Ethnopolitics in Amicable Society 62 Chapter 6. Estonia: Accommodative Ethnopolitics in Polarized Society 86 Part III Conclusion Chapter 7. Conclusion and Implications 108 Appendices 123 References 128 iii Abbreviations of Political Parties’ Name ATAKA Political Party Atack (Bulgaria) AUR Alliance for Romanian Unity (Romania) AWS Election Action Solidarity (Poland) BBB Bulgarian Business Bloc (Bulgaria) CDR Democratcid Convention of Romania (Romania) ChD Christian Democracy (Poland) DPS Democratic Party Saimnieks (Latvia) DSS Democratic Party Slovenia (Slovenia) DU Democratic Union of Slovakia (Slovakia) EK Estonian Citizens (Estonia) EME Estonia Country People’s Party (Estonia) ERSP Estonia Nationalist Independence Party (Estonia) ERL Estonia People’s Union EURP Estonia United -

Selecting Candidates for the EP Elections

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT C: CITIZENS' RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS The Selection of Candidates for the European Parliament by National Parties and the Impact of European Political Parties STUDY Abstract This study compares the procedures applied by national political parties when they select their candidates for the European elections. It analyses the background in national law, the formal party statutes and the informal processes preparing the final selection. The report covers the calendar, selection criteria and structural characte- ristics of candidate nomination in the major political parties of the Member States, including the impact of European political parties. October 2009 PE 410.683 EN This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Constitutional Affairs. The paper is published in English. AUTHORS Jean-Benoît Pilet, Cevipol, Université Libre de Bruxelles Rumyana Kolarova, Vladimir Shopov, Bulgarian EC Studies Association (BECSA) Mats Braun, Vít Beneš, Jan Karlas , Institute of International Relations, Prague Mette Buskjær Christensen, Ian Manners, Danish Inst. for International Studies Mathias Jopp, Tobias Heller, Jeannette Pabst, IEP, Berlin Piret Ehin, Institute of Government and Politics, University of Tartu. Antonis Papayannidis, Nikos Frangakis, Anna Vallianatou, Greek Centre of European Studies and Research Ignacio Molina, Elcano Royal Institute of International Studies, Madrid Olivier Rozenberg, Centre de recherches politiques, Sciences Po, Paris Joseph Curtin, IIEA, Dublin Giulia Sandri, Cevipol, Université Libre de Bruxelles Achilles C. Emilianides, Christina Ioannou, Giorgos Kentas, Centre for Scientific Dialogue and Research, Cyprus Toms Rostoks, Veiko Spolītis, Latvian Institute of International Affairs Gabriella Ilonszki, Réka Várnagy, Corvinus University, Budapest Eva Huijbregts, Nel van Dijk, Institute for Political Participation, Amsterdam Nieves E. -

Online Appendix

Intergenerational Justice Review Sundström, Aksel / Stockemer, Daniel (2018): Youth representation in the European Parliament: The limited effect of political party characteristics. In: Intergenerational Justice Review, 4 (2), 68- 78. Online Appendix List of parties, English names Action - Liberal Alliance Bulgarian People's Union Action of Dissatisfied Citizens Bulgarian Socialist Party Agalev - Groen Canary Coalition Agrarian Union Catholic-National Movement Alliance for the Future of Austria Centre Democrats Alliance of Free Democrats Centre of Social Democrats Alliance of the New Citizen Centre Party Alliance of the Overseas Centre Union of Lithuania Alternative for Germany Christian and Democratic Union – Andalusian Party Czechoslovak People's Party Aragonese Regionalist Party Christian Democratic Appeal Aralar Christian Democratic Centre Attack Christian Democratic Movement Austrian People's Party Christian Democratic People's Party Basque Nationalist Party Christian Democratic Union Basque Solidarity Christian Democrats Bloc of the Left Christian Democrats / League Blue Coalition Christian Social Party Bonino List Christian Social People's Party British National Party Christian Social Union Bulgaria Without Censorship Christian Union - Reformed Political Party Bulgarian Agrarian National Union Christian-Democrat and Flemish 1 Intergenerational Justice Review Citizens - Party of the Citizenry Danish Social-Liberal Party Citizens for European Development of Democracy Bulgaria Democratic and Social Centre Citizens' Movement Democratic -

Economic Voting in Estonia

Central European University Sari Rannanpää Department of Political Science Doctoral Candidate Departmental Doctoral Seminar 13.11.2008 Economic Voting in Estonia Foreword This paper is a by-product of my research into Estonian politics, labour law and tripartism. I got interested in the voting patterns of Estonia, and wanted to test how feasible would it be to use Boolean algebra/QCA in the research of economic voting, given the small number of cases. I would ideally work this paper into a journal article, possibly including Latvia and Lithuania as well – I would be more than happy to receive comments and suggestions that would make it into a publishable piece. Abstract In this paper, I will focus on macro-level economic voting in Estonia. I will test three economic voting hypotheses on four Estonian general elections between 1995 and 2007, using Boolean algebra. To begin with, I will briefly discuss the specificities of economic voting in Central Europe during transition. Then, I will give a narrative of the political and economic developments in Estonia, highlighting the general elections and the coalition politics. Afterwards I will move on to discuss the economic voting hypotheses and illustrate the Estonian case study in parallel. First, I will test the vote-popularity function and show that only when the GDP was growing and unemployment decreasing country-wide did the incumbent party win the general elections. Then, using Fidrmuc’s party responsibility hypothesis, I will show that when unemployment is high in the whole country, the Centre Party wins in most Estonian regions. Finally, I will illustrate, by using Tucker’s transition hypothesis, that when disaggregating national voting patterns, one can easily find that left- leaning parties are more popular in those Estonian regions where unemployment levels are higher – plus their popularity rises together with the rise of unemployment in most of the regions. -

Estonian Political Parties in the Mid-2010S Lanko, Dmitry

www.ssoar.info Estonian Political Parties in the mid-2010s Lanko, Dmitry Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Lanko, D. (2015). Estonian Political Parties in the mid-2010s. Baltic Region, 2, 50-57. https:// doi.org/10.5922/2079-8555-2015-2-5 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Free Digital Peer Publishing Licence This document is made available under a Free Digital Peer zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den DiPP-Lizenzen Publishing Licence. For more Information see: finden Sie hier: http://www.dipp.nrw.de/lizenzen/dppl/service/dppl/ http://www.dipp.nrw.de/lizenzen/dppl/service/dppl/ Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-51269-6 Domestic Policies DOMESTIC POLICIES The article provides an analysis of po- ESTONIAN litical party system of the Republic of Es- tonia in the mid-2010s. The analysis is POLITICAL PARTIES based on the works of Moris Duverger. As one might expect, the establishment of pro- IN THE MID-2010S portionate electoral system in Estonia has resulted in the formation of a multi-party system, in which no single party dominates in the Parliament even in a short run. The D. Lanko* article demonstrates that though the Esto- nian political party system develops in line with the tendencies typical of political party systems of most European countries, some of its elements are more common to post- communist countries. It indicates that the political party system in Estonia has stabi- lized throughout the past decade. -

EU Grant Agreement Number: 290529 Project Acronym: ANTICORRP

This project is co-funded by the Seventh Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development of the European Union EU Grant Agreement number: 290529 Project acronym: ANTICORRP Project title: Anti-Corruption Policies Revisited Work Package: WP3, Corruption and governance improvement in global and continental perspectives Title of deliverable: D3.3) Nine process tracing case study reports on selected countries Process-tracing case study report on Estonia Due date of deliverable: 31 May 2015 Actual submission date of the first draft: 31 May 2015 Editor: Alina Mungiu-Pippidi Author: Valts Kalniņš (Centre for Public Policy PROVIDUS) With input by Aare Kasemets (Estonian Academy of Security Sciences) Organization name of lead beneficiary for this deliverable: Centre for Public Policy PROVIDUS Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Seventh Framework Programme Dissemination Level PU Public X PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) Co Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) The information and views set out in this publication are those of the author(s) only and do not reflect any collective opinion of the ANTICORRP consortium, nor do they reflect the official opinion of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the European Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information. 1 Process-tracing case study report on Estonia Valts Kalniņš Centre for Public Policy (PROVIDUS) [email protected] KEYWORDS Corruption, Anti-Corruption, Particularism, Reforms, Universalism, Estonia \\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\ © 2015 GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies. -

IN the ABSENCE of ANTAGONISM? RETHINKING EASTERN EUROPEAN POPULISM in the EARLY 2000S

East European Quarterly Vol. 45, No. 1-2 pp. 1-25, March-June 2017 © Central European University 2017 ISSN: 0012-8449 (print) 2469-4827 (online) IN THE ABSENCE OF ANTAGONISM? RETHINKING EASTERN EUROPEAN POPULISM IN THE EARLY 2000s Li Bennich-Björkman Department of Government Uppsala University Andreas Bågenholm Department of Political Science University of Gothenburg Andreas Johansson Heinö Department of Political Science University of Gothenburg Abstract This article argues that a close analysis of the early 2000s allegedly populist parties in post-communist Europe allows us to better understand their novelty at the time, what they brought to party politics, and to better explain the dynamic of politics in the region. The central argument is that there were pivotal parties that held a universalist and community-seeking orientation. The article analyzes three electorally successful parties in Eastern Europe, the National Movement Simeon II (NDSV) in Bulgaria, Jaunais Laiks (JL) in Latvia, and Res Publica (ResP), and uses interviews with party representatives, secondary literature, additional documents and published interviews. The findings indicate that these parties share the common vision of a restored community after a decade of social, economic, and political turmoil. Their message of social harmony was rooted in a decade of partisan politics and multi-party system that enhanced competitive views. Keywords: populism, restored community, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia Authors’ correspondence e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] In the Absence of Antagonism? Introduction When the post-communist democracies entered their second decade as multi- party polities in the early 2000s, a new type of political parties emerged. -

Institutional Design and Party Membership Recruitment in Estonia

INSTITUTIONAL DESIGN AND PARTY MEMBERSHIP RECRUITMENT IN ESTONIA ALISON SMITH UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD Abstract: Political party membership is generally considered to be a declining phenomenon in western democracies, and is expected to remain low in central and east Europe.1 The explanation for this state of affairs has centred on the legacy of communism, and the availability of mass media and state funding from the early days of democratization. Yet in some post- communist party systems, membership has risen since 2000. In this article, the reasons for this counterintuitive finding are examined in the case of Estonia. Using elite surveys and interviews, I argue that electoral institutions have influenced the value of members to political parties. Estonia’s small district open-list electoral system and small municipal districts create a demand for members as candidates, grassroots campaigners and “ambassadors in the community.” Furthermore, state subsidies are insufficient to fund expensive modern campaigns. Thus, members play an important role in Estonian political parties. ince the 1960s, scholars have noted the declining role of members in Spolitical parties.2 In the modern world of mass media communications Alison Smith is Lecturer in Comparative Government, Lady Margaret Hall, St Antony’s College, University of Oxford, 62 Woodstock Road, Oxford, OX2 6JF UK, [email protected] Acknowledgements: I wish to thank the ESRC for funding this research, and Paul Chaisty, Emmet C. Tuohy and the two anonymous reviewers of this journal for their assistance and comments. 1 Ingrid van Biezen. 2003. Political Parties in New Democracies: Party Organization in Southern and East-Central Europe, Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan; Petr Kopecký.