Earl Kemp: Ei54

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arch : Northwestern University Institutional Repository

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Myth and the Modern Problem: Mythic Thinking in Twentieth-Century Britain A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Matthew Kane Sterenberg EVANSTON, ILLINOIS December 2007 2 © Copyright by Matthew Kane Sterenberg 2007 All Rights Reserved 3 ABSTRACT Myth and the Modern Problem: Mythic Thinking in Twentieth-Century Britain Matthew Sterenberg This dissertation, “Myth and the Modern Problem: Mythic Thinking in Twentieth- Century Britain,” argues that a widespread phenomenon best described as “mythic thinking” emerged in the early twentieth century as way for a variety of thinkers and key cultural groups to frame and articulate their anxieties about, and their responses to, modernity. As such, can be understood in part as a response to what W.H. Auden described as “the modern problem”: a vacuum of meaning caused by the absence of inherited presuppositions and metanarratives that imposed coherence on the flow of experience. At the same time, the dissertation contends that— paradoxically—mythic thinkers’ response to, and critique of, modernity was itself a modern project insofar as it took place within, and depended upon, fundamental institutions, features, and tenets of modernity. Mythic thinking was defined by the belief that myths—timeless rather than time-bound explanatory narratives dealing with ultimate questions—were indispensable frameworks for interpreting experience, and essential tools for coping with and criticizing modernity. Throughout the period 1900 to 1980, it took the form of works of literature, art, philosophy, and theology designed to show that ancient myths had revelatory power for modern life, and that modernity sometimes required creation of new mythic narratives. -

BOOKNEWS from ISSN 1056–5655, © the Poisoned Pen, Ltd

BOOKNEWS from ISSN 1056–5655, © The Poisoned Pen, Ltd. 4014 N. Goldwater Blvd. Volume 26, Number 11 Scottsdale, AZ 85251 November Booknews 2014 480-947-2974 [email protected] tel (888)560-9919 http://poisonedpen.com Happy holidays to all…and remember, a book is a present you can open again and again…. AUTHORS ARE SIGNING… Some Events will be webcast at http://new.livestream.com/poisonedpen. TUESDAY DECEMBER 2 7:00 PM SUNDAY DECEMBER 14 12:00 PM Gini Koch signs Universal Alien (Daw $7.99) 10th in series Amy K. Nichols signs Now That You’re Here: Duplexity Part I WEDNESDAY DECEMBER 3 7:00 PM (Random $16.99) Ages 12+ Lisa Scottoline signs Betrayed (St Martins $27.99) Rosato & THURSDAY DECEMBER 18 7:00 PM Christmas Party Associates Hardboiled Crime discusses Cormac McCarthy’s No Country SATURDAY DECEMBER 6 10:30 AM for Old Men ($15) Coffee and Crime discusses Christmas at the Mysterious Book- CLOSED FOR CHRISTMAS AND NEW YEAR’S DAY shop ($15.95) SATURDAY DECEMBER 27 2:00 PM MONDAY DECEMBER 9 7:00 PM David Freed signs Voodoo Ridge (Permanent Press $29) Cordell Bob Boze Bell signs The 66 Kid; Raised on the Mother Road Logan #3 (Voyageur Press $30) Growing up on Route 66. Don’t overlook THURSDAY JANUARY 8 7:00 PM the famous La Posada Hotel’s Turquoise Room Cookbook ($40), Charles Todd signs A Fine Summer’s Day (Morrow $26.99) Ian Signed by Chef Sharpe, flourishing today on the Mother Road Rutledge TUESDAY DECEMBER 10 7:30 PM FRIDAY JANUARY 9 7:00 PM Thrillers! EJ Copperman signs Inspector Specter: Haunted Guesthouse Matt Lewis signs Endgame ($19.99 trade paperback) Debut Mystery #6 (Berkley ($7.99) thriller FRIDAY DECEMBER 12 5:00-8:00 PM 25th Anniversary Party Brad Taylor signs No Fortunate Son (Dutton $26.95) Pike Logan The cash registers will be closed. -

Efanzines.Com—Earl Kemp: E*

Vol. 7 No. 5 October 2008 -e*I*40- (Vol. 7 No. 5) October 2008, is published and © 2008 by Earl Kemp. All rights reserved. It is produced and distributed bi-monthly through efanzines.com by Bill Burns in an e-edition only. Happy Halloween! by Steve Stiles Contents—eI40—October 2008 Cover: “Happy Halloween!,” by Steve Stiles …Return to sender, address unknown….30 [eI letter column], by Earl Kemp The Fanzine Lounge, by Chris Garcia The J. Lloyd Eaton Collection, by Rob Latham and Melissa Conway Help Yourself to Eaton!, by Earl Kemp and Chris Garcia Eighty Pounds of Paper, by Earl Kemp It Just Took a Little Longer Than I Thought it Would, by Richard Lupoff SLODGE, by Jerry Murray Back cover: “Run, Baby, Run,” by Ditmar [Martin James Ditmar Jenssen] In the only love story he [Kilgore Trout] ever attempted, “Kiss Me Again,” he had written, “There is no way a beautiful woman can live up to what she looks like for any appreciable length of time.” The moral at the end of that story is this: Men are jerks. Women are psychotic. -- Kurt Vonnegut, Timequake THIS ISSUE OF eI is for the J. Lloyd Eaton Collection of Science Fiction, Fantasy, Horror, and Utopian Literature, housed in the Special Collections & Archives Department of the Tomás Rivera Library at UCRiverside. # As always, everything in this issue of eI beneath my byline is part of my in-progress rough-draft memoirs. As such, I would appreciate any corrections, revisions, extensions, anecdotes, photographs, jpegs, or what have you sent to me at [email protected] and thank you in advance for all your help. -

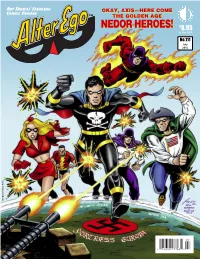

NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 Th.E9 U5SA

Roy Tho mas ’Sta nd ard Comi cs Fan zine OKAY,, AXIS—HERE COME THE GOLDEN AGE NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 th.e9 U5SA No.111 July 2012 . y e l o F e n a h S 2 1 0 2 © t r A 0 7 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 111 / July 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek, William J. Dowlding Cover Artist Shane Foley (after Frank Robbins & John Romita) Cover Colorist Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Deane Aikins Liz Galeria Bob Mitsch Contents Heidi Amash Jeff Gelb Drury Moroz Ger Apeldoorn Janet Gilbert Brian K. Morris Writer/Editorial: Setting The Standard . 2 Mark Austin Joe Goggin Hoy Murphy Jean Bails Golden Age Comic Nedor-a-Day (website) Nedor Comic Index . 3 Matt D. Baker Book Stories (website) Michelle Nolan illustrated! John Baldwin M.C. Goodwin Frank Nuessel Michelle Nolan re-presents the 1968 salute to The Black Terror & co.— John Barrett Grand Comics Wayne Pearce “None Of Us Were Working For The Ages” . 49 Barry Bauman Database Charles Pelto Howard Bayliss Michael Gronsky John G. Pierce Continuing Jim Amash’s in-depth interview with comic art great Leonard Starr. Rod Beck Larry Guidry Bud Plant Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! Twice-Told DC Covers! . 57 John Benson Jennifer Hamerlinck Gene Reed Larry Bigman Claude Held Charles Reinsel Michael T. -

SF COMMENTARY 101 February 2020 129 Pages

SF COMMENTARY 101 February 2020 129 pages JAMES ‘JOCKO’ ALLEN * GEOFF ALLSHORN * JENNY BLACKFORD * RUSSELL BLACKFORD * STEPHEN CAMPBELL * ELAINE COCHRANE * BRUCE GILLESPIE * DICK JENSSEN * EILEEN KERNAGHAN * DAVID RUSSELL * STEVE STILES * TIM TRAIN * CASEY JUNE WOLF * AND MANY MANY OTHERS Cover: Ditmar (Dick Jenssen): ‘Trumped!’. S F Commentary 101 February 2020 129 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 101, February 2020, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3088, Australia. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. DISTRIBUTION: Either portrait (print equivalent) or landscape .PDF file from eFanzines.com: http://efanzines.com or from my email address: [email protected]. FRONT COVER: Ditmar (Dick Jenssen): ‘Tumped!’. BACK COVER: Steve Stiles (classic reprint from cover of SF Commentary 91.) PHOTOGRAPHS: Elaine Cochrane (p. 7); Stephen Silvert (p. 11); Helena Binns (pp. 14, 16); Cat Sparks (p. 31); Leigh Edmonds (pp. 62, 63); Casey Wolf (p. 81); Richard Hyrckiewicz (p. 113); Werner Koopmann (pp. 127, 128). ILLUSTRATIONS: Steve Stiles (pp. 11, 12, 23); Stephen Campbell (pp. 51, 58); Chris Gregory (p. 78); David Russell (pp. 107, 128) Contents 30 RUSSELL BLACKFORD 41 TIM TRAIN SCIENCE FICTION AS A LENS INTO THE FUTURE MY PHILIP K. DICK BENDER 40 JENNY BLACKFORD 44 CASEY JUNE WOLF INTERVIEWS WRITING WORKSHOPS AT THE MUSLIM SCHOOL EILEEN KERNAGHAN 2 4 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY 20 BRUCE GILLESPIE FRIENDS The postal path to penury 4 BRUCE GILLESPIE The future is now! 51 LETTERS OF COMMENT 6 BRUCE GILLESPIE AND ELAINE COCHRANE Leanne Frahm :: Gerald Smith :: Stephen Camp- Farewell to the old ruler. Meet the new rulers. -

1943 Retrospective Hugo Award Results

Worldcon 76 in San Jose PO Box 61363 [email protected] Sunnyvale CA 94088-1363, +1-408-905-9366 USA For Immediate Release 1943 RETROSPECTIVE HUGO AWARD WINNERS REVEALED IN SAN JOSE, CA WORLDCON 76 REVEALS WINNERS FOR SCIENCE FICTION’S MOST PRESTIGIOUS FAN-NOMINATED AWARD SAN JOSE, CA, August 16, 2018: The winners of the 1943 Retrospective Hugo Awards were announced on Thursday, August 16, 2018, at the 76th World Science Fiction Convention. 703 valid ballots (688 electronic and 15 paper) were received and counted from the members of the 2018 World Science Fiction Convention. The Hugo Awards, presented first in 1953 and annually since 1955, are science fiction’s most prestigious award, and one of the World Science Fiction Convention’s unique and distinguished institutions. Since 1993, Worldcon committees have had the option of awarding Retrospective Hugo Awards for past Worldcon years prior to 1953 where they had not been presented 25, 50, or 100 years prior to the contemporary convention, with the exception of the hiatus during World War II when no Worldcon was convened. A recent change in this policy has now allowed for Retro Hugos to be awarded for the years 1942-1945. 1943 Retrospective Hugo Award Winners Best Fan Writer Forrest J Ackerman Best Fanzine Le Zombie, edited by Arthur Wilson "Bob" Tucker Best Professional Artist Virgil Finlay Best Editor - Short Form John W. Campbell Best Dramatic Presentation - Short Form Bambi, written by Perce Pearce, Larry Morey, et al., directed by David D. Hand et al. (Walt Disney Productions) For Immediate Release more Page 2 1943 RETROSPECTIVE HUGO AWARD WINNERS REVEALED IN SAN JOSE, CA Best Short Story "The Twonky," by Lewis Padgett (C.L. -

(Title Stolen from Joan Baez) Time and Culture

Time is Just a Four-Letter What then is time? • If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to Word explain it to him who asks, I do not know. • St Augustine Peter Watson • Time is what we don’t have enough of. (title stolen from Joan Baez) What does a clock measure? Where are we going? • What does "prediction" mean? 1. Time and Language: How we talk about time • When did time measurement start? • Do we experience time in the same way? 2.Stonehenge to Caesium: How we Measure Time • Why does time pass quicker as we get old? • What defines the direction of time? 3.Bicycle Pumps and Rice Puddings: Time’s Arrow • Physiological Time: what is a biological clock? • How short a time can we perceive? 4.Going Straight in a Bent Space: How Matter • What exactly is causality? bends Time • Is time travel possible? 5.Grouse, Hurricanes and Dead Cats: How to • If so, why can't we do it? predict • If not, what forbids it? • How do we know that two clocks measure the same time? 6.The Beginning and the End • How are time and space linked? • Is time "smooth"? 7.“All You Zombies ....”: Time travel, Good • Did time begin? Literature and Bad Science • Will it end? Time and Culture Sources: Books (non-fiction): **Time Machines (Paul J. Nahin, also with K. S. Thorne) Note we will be using “culture” generically Time Travel in Einstein’s Universe (J. Richard Gott) In Search of Time: The History, Physics, and Philosophy of Time (Dan Falk) • Literature About Time (Paul Davies) ** Physics of Star Trek (Lawrence Krauss) Theatre ** An Experiment with Time (J. -

Henry Kuttner, a Memorial Symposium

EDITED BY K /\ R E N A N 0 E R S 0 M A S E V A G R A M ENTERPRISE Tomorrow and. tomorrow "bring no more Beggars in velvet, Blind, mice, pipers'- sons; The fairy chessmen will take wing no more In shock and. clash by night where fury runs, A gnome there was, whose paper ghost must know That home there’s no returning -- that the line To his tomorrow went with last year’s snow, Gallegher Plus no longer will design Robots who have no tails; the private eye That stirred two-handed engines, no more sees. No vintage seasons more, or rich or wry, That tantalize us even to the lees; Their mutant branch now the dark angel shakes Arid happy endings end when the bough breaks. Karen Anderson 2. /\ MEMORIAL symposium. ■ In Memoriams Henry Kuttnei; (verse) Karen Anderson 2 Introduction by the Editor 4 Memoirs of a Kuttner Reader Poul Anderson 4 The Many Faces of Henry Kuttner Fritz Leiher 7 ’•Hank Helped Me” Richard Matheson 10 Ray Bradbury 11 The Mys^&r.y Hovels of Henry Kuttner Anthony. Boucher . .; 12 T^e Closest Approach • Robert Bloch . 14 Extrapolation (fiction) Henry Kuttner Illustrated by John Grossman ... (Reprinted from The Fanscient, Fall 1948) 19 Bibliography of the Science-Fantasy Works of Henry.. Kuttner Compiled by Donald H..Tuck 23 Kotes on Bylines .. Henry Kuttner ... (Reproduced from a letter) 33 The verse on Page 2 is reprinted from the May, 1958 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science-Fiction, Illustrations by Edd Cartier on pages 9, 18, and 23 are reproduced respectively from Astounding Science Fiction. -

Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Guides to Manuscript Collections Search Our Collections 2006 0749: Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006 Marshall University Special Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/sc_finding_aids Part of the Fiction Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Playwriting Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006, Accession No. 2006/04.0749, Special Collections Department, Marshall University, Huntington, WV. This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Search Our Collections at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Guides to Manuscript Collections by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 0 REGISTER OF THE NELSON SLADE BOND COLLECTION Accession Number: 2006/04.749 Special Collections Department James E. Morrow Library Marshall University Huntington, West Virginia 2007 1 Special Collections Department James E. Morrow Library Marshall University Huntington, WV 25755-2060 Finding Aid for the Nelson Slade Bond Collection, ca.1920-2006 Accession Number: 2006/04.749 Processor: Gabe McKee Date Completed: February 2008 Location: Special Collections Department, Morrow Library, Room 217 and Nelson Bond Room Corporate Name: N/A Date: ca.1920-2006, bulk of content: 1935-1965 Extent: 54 linear ft. System of Arrangement: File arrangement is the original order imposed by Nelson Bond with small variations noted in the finding aid. The collection was a gift from Nelson S. Bond and his family in April of 2006 with other materials forwarded in May, September, and November of 2007. -

2019-07-08 Catalog P

Pulp-related books and periodicals available from Mike Chomko for July and August 2019 Given that I’m writing these words in early September, I’m way behind on my bookselling chores. As I’ve relayed via email, between PulpFest 2019 and helping my wife with her mother — now in hospice care — this summer has been extremely busy. PulpFest is over for another year — actually eleven months, given the timing of this catalog. The convention’s organizing committee is already working on next year’s gathering. It will take place August 6 - 9 at the DoubleTree by Hilton Pittsburgh — Cranberry, located in Mars, Pennsylvania. PulpFest 2020 will focus on Bradbury, BLACK MASK, and Brundage. We may even throw in a touch of Brackett and Burroughs for good measure. In October, we’ll be announcing our very special guest of honor. Over the Labor Day weekend, Dianne and I drove to the Burlington area of Vermont to acquire a substantial collection of pulps, digests, vintage paperbacks, first edition hardcovers, underground comics, fanzines, and more. The primary focus of the magazine collection is the science fiction genre. There are also miscellaneous periodicals from the adventure, detective, hero, spicy, and war genres. The collection contains magazines in both the pulp and digest formats. The vintage paperbacks run the gamut of genres that are popular in that area of book collecting. PulpFest will begin selling the collection via auction during our 2020 convention. Given its size, it will take a number of years to disperse the entire collection. Now begins the difficult and time-consuming work of organizing, cataloging, lotting, and photographing the collection. -

Twentieth- Century Crime Fiction

Twentieth-Century Crime Fiction This page intentionally left blank Twentieth- Century Crime Fiction Lee Horsley Lancaster University 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Lee Horsley The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available ISBN ––– –––– ISBN ––– –––– pbk. -

Earl Kemp: E*I* Vol. 4 No. 6

market for science fiction in terms of properties bought. However, I also feel that the big money and success will continue to be in the area of the movies. Television still seems to be a very limited market and only Star Trek has been a real success in the past 20 years. Even the success of Star Trek was limited; it managed only three seasons compared to the ten-to fifteen-plus seasons of Gunsmoke and other long-running television shows. Star Trek was good because it showed there was a market for science fiction. However, the ratings showed that the market was limited. Your question implies that we should consider other mediums such as computer terminals, video cassettes, etc. I don’t really see much chance for science fiction’s developing a significant market in these areas. I may be wrong, but I feel that books have been around a long time and will continue to be around. I would personally rather read a book than watch television or a movie, and I think the people science fiction appeals to feel the same way. 4) Can it really be almost 20 years since I helped Earl Kemp put together the first Who Killed Science Fiction? Age seems to sneak up on us. I look back and bits and pieces come to my memory. I still remember starting out early one Saturday morning to go to Lynn Hickman’s house to do the printing. My memory of the trip was that it was sometime in the winter. I don’t remember where Lynn lived then, but an examination of a map suggests that Dixon, Illinois, is the most likely candidate.