Look out at the Ocean, and You Might See a Trash-Free Environment. But

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on the Availability of Whale Meat in Greenland

1 Greenland survey: 77% of restaurants served whale meat in 2011/2012 Greenland claims that its current Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling (ASW) quota of 175 minke whales, 16 fin whales, nine humpback whales and two bowhead whales a year is insufficient to meet the nutritional needs of Greenlanders (people born in Greenland). It claims in its 2012 Needs Statement that West Greenland alone now requires 730 tonnes of whale meat annually. Greenland has around 50 registered restaurants used by tourists, including several in hotels, plus another 25 smaller "cafeterias, hot dog stands, grill bars, ice cream shops, etc.” which are licensed separately.1 WDCS, the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society, visited Greenland in May 2011 to assess the availability of whale meat in registered restaurants. In September 2011, WDCS and the Animal Welfare Institute (AWI) visited again. In June 2012, AWI conducted (i) a telephone and email survey of all restaurants (31) for which contact information (phone/email) was available and (ii) extensive internet research in multiple languages of web entries referencing whale meat in Greenland’s restaurants in 2011/2012. Whale meat, including fin, bowhead and minke whale, was available to tourists at 24 out of 31 (77.4%) restaurants visited, contacted, and/or researched online in Greenland in 2011/2012. In addition, one other restaurant for which there was no online record of it serving whale meat indicated, when contacted, that though it did not currently have whale meat on the menu it could be provided if requested in advance for a large enough group. Others that did not have whale meat said that they could provide an introduction to a local family that would. -

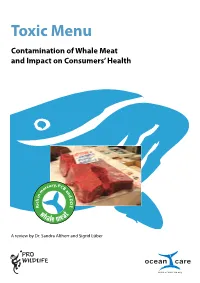

Toxic Menu – Contamination of Whale Meat

Toxic Menu Contamination of Whale Meat and Impact on Consumers’ Health ry, P rcu CB e a m n d n i D h D c i T . R wh at ale me A review by Dr. Sandra Altherr and Sigrid Lüber Baird‘s beaked whale, hunted and consumed in Japan, despite high burdens of PCB and mercury © Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) © 2009, 2012 (2nd edition) Title: Jana Rudnick (Pro Wildlife), Photo from EIA Text: Dr. Sandra Altherr (Pro Wildlife) and Sigrid Lüber (OceanCare) Pro Wildlife OceanCare Kidlerstr. 2, D-81371 Munich, Germany Oberdorfstr. 16, CH-8820 Wädenswil, Switzerland Phone: +49(089)81299-507 Phone: +41 (044) 78066-88 [email protected] [email protected] www.prowildlife.de www.oceancare.org Acknowledgements: The authors want to thank • Claire Bass (World Society for the Protection of Animals, UK) • Sakae Hemmi (Elsa Nature Conservancy, Japan) • Betina Johne (Pro Wildlife, Germany) • Clare Perry (Environmental Investigation Agency, UK) • Annelise Sorg (Canadian Marine Environment Protection Society, Canada) and other persons, who want to remain unnamed, for their helpful contribution of information, comments and photos. - 2 - Toxic Menu — Contamination of Whale Meat and Impact on Consumers’ Health Content 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 2. Contaminants and pathogens in whales ....................................................................................................... -

Mercury in Fish – Background to the Mercury in Fish Advisory Statement

Mercury in fish – Background to the mercury in fish advisory statement (March 2004) Food regulators regularly assess the potential risks associated with the presence of contaminants in the food supply to ensure that, for all sections of the population, these risks are minimised. Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) has recently reviewed its risk assessment for mercury in food. The results from this assessment indicate that certain groups, particularly pregnant women, women intending to become pregnant and young children (up to and including 6 years), should limit their consumption of some types of fish in order to control their exposure to mercury. The risk assessment conducted by FSANZ that was published in 2004 used the most recent data and knowledge available at the time. FSANZ intends toreview the advisory statement in the future and will take any new data and scientific evidence into consideration at that time. BENEFITS OF FISH Even though certain types of fish can accumulate higher levels of mercury than others, it is widely recognised that there are considerable nutritional benefits to be derived from the regular consumption of fish. Fish is an excellent source of high biological value protein, is low in saturated fat and contains polyunsaturated fatty acids such as essential omega-3 polyunsaturates. It is also a good source of some vitamins, particularly vitamin D where a 150 g serve of fish will supply around 3 micrograms of vitamin D – about three times the amount of vitamin D in a 10 g serve of margarine. Fish forms a significant component of the Australian diet with approximately 25% of the population consuming fish at least once a week (1995 Australian National Nutrition Survey; McLennan & Podger 1999). -

Whose Whale Is That? Diverting the Commodity Path

17 Whose Whale is That? Diverting the s - but by no means all - to switch from Commodity Path or a 'green' legitimacy and how they aractelistics on those who sponsor the Arne Kalland d animal welfare discourses as the Nordic Institulc of Asian Studies, Copenhagen y (Appadurai 1986: 13), companies have acquired ity) by economically supporting environmental government agencies have obtained the same in legitimacy. Both exchanges have been wrapped in the metaphors of ABmCTUsing concepts from Appadurai's The Social Life of Things,this paper seeks to 'goodness.' Thus, the "super-whale' has taken on a life as a com- analyze the Simultaneous processes of decommoditization of meat, oil and whale n. ~~commoditizationof meat and oil and commoditization of the products and the commoditization of a symbolic 'super-whale,' i.e. how an old established processes in the diversion of the commodity path, and commodity path (commercial whaling) has been interrupted by a new one (low-consumptive IWC meetings and other 'tournaments of value,' use of whales). Through the culwal framework of ecological and animal rights discourses, government agencies, politicians and industries have been able to acquire green legitimacy ciety' are contested (Appadurai 198621). and protection in return for supporting environmental and animal rights organizations.fis or ownership of whales in order to exchange has been legitirnised through the annual meetings of the International whaling s for appropriating nature. It is the Commission, whale rescue operations andother 'tournamcntsofvalue.'~o~the '~~~~.~h~. imal rights group on the one hand le' is tuned into a commodity and consumed raises also the imponant question about rights r - brought about by skilful manipulation in whales. -

Fish Sausage Manufacturing

CHAPTER 10 Fish Sausage Manufacturing KEISHI AMANO Marine Food Preservation Division, Tokai Regional Fisheries Research Laboratory, Tokyo, Japan I. Introduction 265 II. Chemical Aspects 267 A. Sodium Chloride and Myosin Extraction 268 B. pH of Raw Jelly 268 C. Polyphosphates 9 26 D. Setting Phenomenon of Raw Fish Jelly 269 III. Raw Materials 270 A. Raw Fish 270 B. Starch 271 C. Fat 271 D. Spices 271 E. Food Additives 272 F. Casings 272 IV. Preparation and Processing 273 V. Recipes 274 A. Whale Meat and Tuna 274 B. Salmon and Tuna 275 C. Shark, Tuna, and Salmon 275 D. Croaker and Tuna 275 E. Black Marlin 275 F. General Remarks 275 VI. Shelf-Life and Bacteriological Problems 276 VII. Quality Control 278 VIII. Chemical Composition 279 References 279 I. Introduction Fish sausage manufacturing in Japan is attracting world wide atten tion because of the rapid expansion of the industry, a growth rate that was never expected even by the entrepreneurs. Before the Second World War, experimental preparation of fish sausage had on occasion been tried by a few fish processing technologists, with rather unsuccessful results. The lack of suitable packaging materials was perhaps the main technological deterrent to the introduction of the new fish product in Japan, but in addition, consumers were not ready to accept a product of this kind. The fish sausage industry in Japan was actually begun in 1953 265 266 KEISHI AMANO by small-scale manufacturers. Average daily production at that time was low, but the industry gradually grew and was taken over by large fishing firms that were able to obtain abundant raw material by using their own fishing fleets. -

April X, 2011

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: September 7, 2016 at 3:01 a.m. EDT Contacts: Amelia Vorpahl, 202.467.1968, 202.476.0632 (cell) or [email protected] Dustin Cranor, 202.341.2267, 954.348.1314 (cell) or [email protected] 1 in 5 Seafood Samples Mislabeled Worldwide, Finds New Oceana Report Oceana Calls on President Obama to Track All Seafood from Boat to Plate as Ocean Leaders Prepare to Gather in DC for Our Ocean Conference WASHINGTON – Today, Oceana released a new report detailing the global scale of seafood fraud, finding that on average, one in five of more than 25,000 samples of seafood tested worldwide was mislabeled. In the report, Oceana reviewed more than 200 published studies from 55 countries, on every continent except for Antarctica. The studies found seafood fraud present in each investigation with only one exception. The studies reviewed also found seafood mislabeling in every sector of the seafood supply chain: retail, wholesale, distribution, import/export, packaging/processing and landing. An interactive map of the global seafood fraud review compiled by Oceana can be found at www.oceana.org/seafoodfraudmap. The report comes as ocean leaders from all over the world prepare to gather in Washington, DC for the Our Ocean Conference next week. Earlier this year, the President’s Task Force on Combating Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing and Seafood Fraud released a proposed rule to address these issues that would require traceability for 13 “at-risk” types of seafood from the fishing boat or farm to the U.S. border. Oceana contends that while this is a good step forward, the government needs to expand the final rule to include all seafood species sold in the U.S. -

Portugal, Canada Discuss Marine Fisheries Vessels Involved in the Harvest

Results of the first full year of joint ers an attractive service. fully guaran sites, how marine life would be affected, research on the tuna and billfish stocks teeing obligations incurred by fishermen and what natural hazards face oil de in the Atlantic Ocean under the Na to finance up to 75 percent of the cost of velopment activities in this region. The tional Marine Fisheries Service-Woods constructing, reconstll.lcting, or recon study is being conducted by the Com Hole Oceanographic Institution ditioning commercial fishing vessels. merce Department agency's Environ Cooperative Game Fish Tagging Pro The capital Construction Fund pro mental Research Laboratories for the gram are included. Over 1,800 game fish gram may be used to obtain deferment Interior Department's Bureau of Land were tagged; 673 of these were sailfish of taxes on certain income derived from Management. released off the southeast coast of commercial fishing operations when Before joining NOAA, Engelmann Florida and off Cozumel, Mexico. such income is deposited in a special was Deputy Manager for the environ Seventy-nine recoveries of tagged game fund with the intention of using it for mental research ofthe U.S. Energy Re fish were recorded in 1974. Amberjacks constructing, acquiring, or recondition search and Development Administra provided the most returns (25) with ing a commercial fishing vessel. Notice tion and its predecessor organization, small bluefin tuna second (19). One of these declarations appeared in the the Atomic Energy Commission. Prior giant bluefin tuna tagged off the Federal Register the week of 22 Sep to that he led the agency's Fallout Bahamas was recaptured off Norway tember 1975. -

Mercury in Seafood: Facts and Discrepancies

[PERSPECTIVE] by Michael T. Morrissey Mercury in Seafood: Facts and Discrepancies disparity exists between there are low-level toxic effects in seafood that it would be health-care professionals. what we read in the popular from MeHg in seafood. detrimental to human health to Articles such as “Mercury in A press and what research- The Environmental Protec- reduce consumption levels. Tuna” in the July 2006 issue of ers are discovering about the tion Agency (EPA) used the Unfortunately, the message Consumer Reports cause further value of eating seafood. Faroe data as the basis for about health benefits from confusion among consumers. Confusion stems mainly its reference doses for MeHg eating seafood was lost in the The article claimed that their from two questions: “What exposure, taking the position 2004 EPA/Food and Drug Admin- (anonymous) “fish-safety levels of methylmercury that a reference dose cannot istration advisory for women of experts” found that even (MeHg) exposure may cause be determined from a study child-bearing age (www.cfsan. light tuna might prove risky to demonstrable harmful effects for (Seychelles) where the data fda.gov/~dms/admehg3b.html). pregnant women and the fetus. humans, especially the fetus?” showed no adverse effects. Americans are risk-adverse in They called on pregnant women and “When do potential risks Recent work shows that their food habits, and the media to “avoid canned tuna entirely,” of MeHg in seafood outweigh the benefits from seafood focused on hypothetical risks needlessly scaring women away the well-documented benefits consumption greatly outweigh and the warnings in the advisory, from one of the best sources of seafood consumption?” the risks. -

The Influence of Indigenous Cultures on the Intern

Creason: Culture Clash: The Influence of Indigenous Cultures on the Intern COMMENTS CULTURE CLASH: THE INFLUENCE OF INDIGENOUS CULTURES ON THE INTERNATIONAL WHALING REGIME INTRODUCTION The cultural values of native populations are a significant source of law, because modem societies develop from the practices and be- liefs of indigenous cultures.' Over time, indigenous customs and tra- ditions are incorporated into contemporary lifestyles.2 The strong in- fluence ancient practices have on present cultures is apparent in the religious, dietary, economic and political facets of today's societies.3 In turn, modem culture influences the laws of a nation.4 Societal preferences, practices and traditions are reflected in the regulations a country creates to govern its people.' Since modem and ancient cul- l. J. Richard Broughton, The Jurisprudenceof Tradition and Justice Scalia's Unwrit- ten Constitution, 103 W. VA. L. REv. 19, 21-26 (2000); Eric N. Weeks, A Widow's Might: Nakaya v. Japan and Japan's Current State of Religious Freedom, 1995 BYU L. REV. 691, 693-94 (1995). 2. Broughton, supra note 1, at 21-22. 3. See generally Chaihark Hahm, Law, Culture, and the Politics of Confucianism, 16 COLUM. J. AsiAN L. 253, 256-58 (2003) (recognizing the significant role of ancient Confucian beliefs in modem Korean society); A.W. Harris, Making the Case for Collective Right: In- digenous Claims to Stocks of Marine Living Resources, 15 GEO. INT'L ENVTL. L. REV. 379, 392 (2003) (discussing the integral role traditional whale hunting plays in the Makah Indians' present day religious, ceremonial and social lives); Tarik Abdel-Monem, Affixing the Blame: Ideologies of HIVAIDS in Thailand,4 SAN DIEGO INT'L L.J. -

Meat Consumption from Stranded Whales and Marine Mammals in New Zealand: Public Health and Other Issues

Meat consumption from stranded whales and marine mammals in New Zealand: Public health and other issues M W Cawthorn Cawthorn & Associates Marine Mammals/Fisheries Consultants 53 Motuhara Road Plimmerton Wellington Published by Department of Conservation Head Office, PO Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand This report was commissioned by Hawke's Bay, Wellington and Otago Conservancies ISSN 1171-9834 1997 Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10-420, Wellington, New Zealand Reference to material in this report should be cited thus: Cawthorn, M.W., 1997 Meat consumption from stranded whales and marine mammals in New Zealand: Public health and other issues. Conservation Advisory Science Notes No. 164, Department of Conservation, Wellington. Keywords: Whales, seals, food preparation (marine mammal), meat quality assessment (marine mammal), flensing, pathogens, contaminants Abstract Interest in the use of stranded whales as a source of food and the use of seals for cultural purposes has been expressed to the Department of Conservation by Ngati Hawea and Ngai Tahu Maori respectively. The known and anecdotal history of consumption of whale and seal meat in New Zealand and elsewhere is briefly discussed. Comments on the palatibility of marine mammal meat and the use of whales and seals as food are presented. Post-stranding damage and carcass contamination result in unsuitability of meat for human consump- tion. Criteria for the assessment of meat quality from stranded animals are presented. The transmission of parasites, particularly Anisakis sp., and the cumulative effects of persistent pesticides and heavy metals from consump- tion of meat from species such as pilot whales is discussed. Meat collection and storage should be conducted under the same conditions and constraints applied to terrestrial mammals. -

Biological Metabolism of Frozen Whale Meat at Subzero Temperatures in Relation to Thaw Rigor

135 Original paper Transactions of the Japan Society of Refrigerating and Air Conditioning Engineers, TransactionsReceived of the date Japan:April Society 14, of2018 Refrigerating;J-STAGE and Advance Air Conditioning published Engineers,date:May 31, 2018 Original Paper Vol.35,No.2(2018),pp.135-139,doi: 10.11322/tjsrae.18 -doi:10_OA 10.11322/tjsrae.18-10 _OA Received date: April 14, 2018; J-STAGE Advance publishied date: May 31, 2018 Biological Metabolism of Frozen Whale Meat at Subzero Temperatures in Relation to Thaw Rigor Hideto FUKUSHIMA*† Naho NAKAZAWA** Koki YAMADA* Masahiro MATSUMIYA* Ritsuko WADA*** Toshimichi MAEDA*** * Department of Marine Science and Resources, Nihon University (1866 Kameino, Fujisawa, Kanagawa 252-0880) ** Department of Food Science and Technology, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology (4-5-7, Konan, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-8477) ***Department of Food Science and Technology, National Fisheries University (2-7-1 Nagata-Honmachi, Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi 759-6595) Summary In many cases, frozen whale meat in the Japanese market is prepared before rigor mortis (pre-rigor). A serious problem for frozen whale meat is the occurrence of thaw rigor, which is the strong development of rigor mortis during thawing. To prepare frozen whale meat without thaw rigor and maintain a high meat pH, the temporal changes in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) contents of frozen meat stored at -2.5, -5.0, -7.5, and -10°C were investigated. The rate of decrease of ATP was higher than that of NAD at all storage temperatures. ATP nearly disappeared after holding the meat at -2.5°C for a few days; however, NAD existed yet, so pH decreased thereafter. -

Chapter I Whales Saved the Japanese

Chapter I Whales Saved the Japanese History of the Japanese love for whales: the Jomon and Yayoi periods The Japanese have been closely tied to whales from ancient times. Whale meat eating goes back a remarkably long way. A great number of bones of cetaceans have been unearthed from various areas including graves and shell mounds of the Jomon period, about 8,000 to 9,000 years ago. “Shell mounds” suggests at least that people in the Jomon period were collecting shell fish as food, which is nowhere near the fact. Subsequently, whale meat was selected as food since, more than anything, whale meat is delicious, which I would like to point out here. Once you eat whale meat, its good taste remains with you, making you want to eat it again. In addition, one whale can feed hundreds or even thousands of people at a time. Furthermore, the bones can be processed into tools and, moreover, bones, teeth, fins and baleen can all be used. Stoneware unearthed from Tsugumenohana Site, Nagasaki Prefecture (Source: Tsugumenohana Iseki no Gaiyo (Overview of Tsugumenohana Site), Shobayashi M. and Baba , Bulletin of the Nagasaki Archaeological Society Vol. 2) 1 Whale’s intervertebral disk used as a workbench for pottery (Unearthed from Saga Site / Tsushima City, Nagasaki Prefecture) The flesh of whales contains large amounts of excellent protein and, considering the dietary habits in those days, eating whale meat could have been dramatically vitalizing. That is why, for ages, the Japanese have been tied to whales. From the shell mound of the Tsugumenohana Site in Hirado City, Nagasaki Prefecture, which has been dated to between the early and the middle phases of the Jomon period, the skeletal remains of many whales, dolphins and sharks have been unearthed.