The Role of SES in Sentencing Severity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shortcomings in the Doctrines of Culpability, Mitigation, and Excuse

University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law 7-13-2021 Individualizing Criminal Law’s Justice Judgments: Shortcomings in the Doctrines of Culpability, Mitigation, and Excuse Paul H. Robinson University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Lindsay Holcomb University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Repository Citation Robinson, Paul H. and Holcomb, Lindsay, "Individualizing Criminal Law’s Justice Judgments: Shortcomings in the Doctrines of Culpability, Mitigation, and Excuse" (2021). Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. 2520. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/2520 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law by an authorized administrator of Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7 2 21 INDIVIDUALIZING CRIMINAL LAW’S JUSTICE JUDGMENTS: SHORTCOMINGS IN THE DOCTRINES OF CULPABILITY, MITIGATION, AND EXCUSE Paul H. Robinson* and Lindsay Holcomb** Abstract In judging an offender’s culpability, mitigation, or excuse, there seems to be general agreement that it is appropriate for the criminal law to take into account such things as the offender’s youthfulness or her significantly low IQ. There is even support for taking account of their distorted perceptions and reasoning induced by traumatic experiences, as in battered spouse syndrome. -

Rasgas, Petronet Sign LNG Supply Deal for India

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Sheikh Salman manifesto aims to rise INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2, 20 COMMENT 18, 19 ARAB WORLD 3, 4 BUSINESS 1-8 FIFA from Qatar budget ‘focusing’ 17,488.96 10,429.36 37.12 INTERNATIONAL 5-16 CLASSIFIED 5 -114.91 -06.61 +1.42 ISLAM 17 SPORT 1-8 on sustainable growth ‘ashes’ -0.65% -0.06% +0.52% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 FRIDAY Vol. XXXVI No. 9954 January 1, 2016 Rabia I 21, 1437 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Hopes on the horizon Blaze engulfs GULF TIMES WISHES ITS Dubai hotel READERS A HAPPY NEW YEAR near world’s In brief tallest tower Reuters QATAR | Offi cial Dubai Emir exchanges ire engulfed a 63-storey sky- New Year greetings scraper in downtown Dubai near HH the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Fthe world’s tallest building last Hamad al-Thani exchanged cables of night, but the block was successfully congratulations with Their Majesties evacuated and there were only light and Highnesses the leaders of injuries, the emirate’s police chief friendly countries on the occasion said. of the New Year, wishing them the Tongues of fl ame shot skywards best of health and happiness and The sun sets on 2015 as people enjoy a pleasant winter evening in Doha’s Aspire Park yesterday. An eventful year for Qatar from one side of the luxury Address their peoples further progress and and the rest of the world has gone down in history. The New Year, 2016, brings with it many hopes and challenges. -

Dissertation Final

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ EPISTEMIC INJUSTICE, RESPONSIBILITY AND THE RISE OF PSEUDOSCIENCE: CONTEXTUALLY SENSITIVE DUTIES TO PRACTICE SCIENTIFIC LITERACY A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in PHILOSOPHY by Abraham J. Joyal June 2020 The Dissertation of Abraham J. Joyal is approved: _____________________________ Professor Daniel Guevara, chair _____________________________ Professor Abraham Stone _____________________________ Professor Jonathan Ellis ___________________________ Quentin Williams Acting Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table Of Contents List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………………………iv Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………....v Chapter One: That Pseudoscience Follows From Bad Epistemic Luck and Epistemic Injustice………………………………………………………………………………………………....1 Chapter Two: The Critical Engagement Required to Overcome Epistemic Obstacles……….37 Chapter Three: The Myriad Forms of Epistemic Luck……………………………………………56 Chapter Four: Our Reflective and Preparatory Responsibilities………………………………...73 Chapter Five: Medina, Epistemic Friction and The Social Connection Model Revisited.…….91 Chapter Six: Fricker’s Virtue Epistemological Account Revisited……………..………………110 Chapter Seven: Skeptical Concerns……………………………………………………………...119 Conclusion: A New Pro-Science Media…………………………………………………………..134 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………………140 iii List of Figures Chainsawsuit Webcomic…………………………………………………………………………….47 Epistemological Figure……………………………………………………………………………....82 -

Yorba Times: Special Edition on Safety Noah Asher Golden Chapman University, [email protected]

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Yorba-Chapman Writing Partnership Anthology of College of Educational Studies Journalistic Writing Spring 2016 Yorba Times: Special Edition on Safety Noah Asher Golden Chapman University, [email protected] Facundo Acevedo Yorba Academy for the Arts Jesse Alonzo Yorba Academy for the Arts Henessy Arana Yorba Academy for the Arts Leslie Arriaga Yorba Academy for the Arts Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/yorba-chapman See nePxat pratge of for the addiBtionilinal gauualthor,s Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Higher Education and Teaching Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Junior High, Intermediate, Middle School Education and Teaching Commons, Nonfiction Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Communication Commons, Other Education Commons, Other Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Publishing Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, and the Technical and Professional Writing Commons Recommended Citation Golden, N.A, et al. (2016). Yorba Times: Special edition on safety. Yorba-Chapman Writing Partnership Anthology of Journalistic Writing. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/yorba-chapman/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Educational Studies at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has -

LOOKING DOWN the ROAD Inside This Issue: Pretlow’S Vehicle Confiscation Bill Addresses Recidivism Issue by William Aiken Jr

Non-Profit Org. - USA, Inc. National Newsletter U.S. POSTAGE PAID Albany, NY Permit #298 RIDEditor: Jane Wyatt Aiken ISSN 1523-861X Volume 37 Number 2 A CITIZEN’S PROJECT TO REMOVE INTOXICATED DRIVERS Fall 2017 P.O. Box 520, Schenectady, New York 12301 LOOKING DOWN THE ROAD Inside this issue: Pretlow’s Vehicle Confiscation Bill Addresses Recidivism Issue By William Aiken Jr. allows the law to step in before these recidivist drunken drivers are able to wreak further havoc on society. Drunken drivers who continually get behind the wheel intoxicated Assemblyman Gary Pretlow, 89th District despite multiple run-ins with the law put all of us in danger. I receive Assemblyman Pretlow responded to my questions regarding his news clippings all the time of such cases. Dennis Drue, who was bill. convicted of killing two high school students while driving drunk on a New York Highway, had five license suspensions and 22 prior What inspired you to write 00995? traffic offenses before he caused this fatal crash. Drue was pushed along in our legal system without ever being held accountable. I was leaving Albany and almost collided with a vehicle driving When his reckless conduct finally caught up with him, it resulted towards me on a one way road. After that experience I felt that in the taking away of two innocent young lives, devastating their people should not be on the road risking the lives of innocent families and friends. people. Fortunately, some of our elected officials are paying attention. The asset forfeiture laws in New York State are very strict when ...and Help RIDley curb DUI/DWI. -

One Dead in Weekend Crash City Officials to Set Goal for Conservation

TUESDAY,APRIL 3, 2018 Inside: 75¢ Trump calls for border legislation. — Page 4B Vol. 90 ◆ No. 2 SERVING CLOVIS, PORTALES AND THE SURROUNDING COMMUNITIES EasternNewMexicoNews.com FUN IN THE SUN One dead in weekend crash ❏ Portales man charged with homicide by vehicle in incident. By Eamon Scarbrough about 5:25 a.m. Saturday STAFF WRITER and found a white pickup [email protected] truck on its driver’s side facing west. “The truck PORTALES — The sus- pect in a fatal crash possi- was in the middle of the bly caused by alcohol on road,” the report said. Saturday told police he was Saldana-Pinales’ vehicle returning home from lay in the field north of the watching a movie at 4:30 highway, according to the a.m., officials said. affidavit. Ricardo Navarrete, 31, of The officer stated that Portales, was arrested Navarrete had “a strong Saturday morning after police say his vehicle odor of an alcoholic bever- struck another car from age emitting from his behind, killing the driver. breath and body,” as well Jose Saldana-Pinales, 41, as “blood shot watery of Portales, was ejected eyes.” from his vehicle after it Navarrete was transport- was rear-ended by ed to the NMSP office in Navarrete’s truck, accord- Clovis, where he consented ing to a press release by the to a breath test. The alco- New Mexico State Police. Saldana-Pinales died at the hol level on Navarrete’s scene. breath was .14, according Efforts to reach Saldana- to the affidavit. Pinales family members Navarrete was charged were not immediately suc- with homicide by vehicle cessful. -

Indoctrination and Social Influence As a Defense to Crime: Are We Responsible for Who We Are?

Missouri Law Review Volume 85 Issue 3 Article 7 Summer 2020 Indoctrination and Social Influence as a Defense to Crime: Are We Responsible for Who We Are? Paul H. Robinson Lindsay Holcomb Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Paul H. Robinson and Lindsay Holcomb, Indoctrination and Social Influence as a Defense to Crime: Are We Responsible for Who We Are?, 85 MO. L. REV. (2020) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol85/iss3/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Missouri Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robinson and Holcomb: Indoctrination and Social Influence as a Defense to Crime: Are We Indoctrination and Social Influence as a Defense to Crime: Are We Responsible for Who We Are? Paul H. Robinson* and Lindsay Holcomb** ABSTRACT A patriotic prisoner of war is brainwashed by his North Korean captors into refusing repatriation and undertaking treasonous anti-American propaganda for the communist regime. Despite the general abhorrence of treason in time of war, the American public opposes criminal liability for such indoctrinated soldiers, yet existing criminal law provides no defense or mitigation because, at the time of the offense, the indoctrinated offender suffers no cognitive or control dysfunction, no mental or emotional impairment, and no external or internal compulsion. -

Undergraduate Lawjournal

UNDERGRADUATE LAW JOURNAL A Registered Student Organization at FAU® Spring 2019 SPRING 2019 UNDERGRADUATE LAW JOURNAL Officers: Editor-in-Chief . Nora Douglas Secretary. Stefania Cardenas Treasurer . .Stephan Schneider Editing Board Amanda Heine, Borina Jean, Cameron Ryan, Emily Herrera, Nery Tavarez, Sandy Larose, Steven Robinson Faculty Advisors Cheryl Arflin, J.D. Anthony Horky, J.D. Paul Koku, Ph.D., J.D. The ULJ would like to thank Holly Pereira, Chris Kuczynski, and Katherine Murphy for their invaluable assistance and Professors Sarah Nielsen, Emre Yersel ,Anthony Horky, Paul Koku, Dalel Bader and Cheryl Arflin for assisting with the mentoring, editing and proofing. The Florida Atlantic University Undergraduate Law Journal is published online by FAU Digital Library and is available at http://journals.fcla.edu/FAU_UndergraduateLawJournal. The Undergraduate Law Journal is also a contributor to an Intercollegiate Undergraduate Law Journal which may be viewed at http://intercollegiatelawjournal.com/. For submission guidelines and membership information, please contact [email protected]. You may also find additional information about the Pre-Law program at FAU at https://www.fau.edu/prelaw. Copyright 2019 Florida Atlantic University Undergraduate Law Journal. Authors retain copyrights, but grant the journal the right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work’s authorship and initial publication in this journal. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contracts for their personal article, as well as offer it for publication in an institutional repository or publish it in a book, etc., provided the article includes an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal. -

HUYEN PHAM Texas A&M University School of Law 1515 Commerce Street ● Fort Worth, TX 76102-6509 [email protected]

HUYEN PHAM Texas A&M University School of Law 1515 Commerce Street ● Fort Worth, TX 76102-6509 [email protected] EDUCATION HARVARD LAW SCHOOL, J.D. Honors: cum laude HARVARD COLLEGE, A.B. in Social Studies Honors: magna cum laude Ford Program Fellowship for Thesis Research Stride-Rite Scholarship for Public Service ARTICLES AND BOOK CHAPTERS Modeling Cooperation: How Federal and Subfederal Authorities Should Work Together to Enforce Immigration Laws (invited), UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS LAW REVIEW (forthcoming 2016), “Symposium on Sanctuary, Detainers, Undocumented Crime and the Law: History, Contemporary Challenges, and Possible Solutions” State-Created Immigration Climates: The Influence of Domestic Migrants, with Pham Hoang Van, 38 UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LAW REVIEW 181 (2016). Measuring the Climate for Immigrants: A State-by-State Analysis (invited), with Pham Hoang Van, in Strange Neighbors: The Role of States in Immigration Policy (edited by G. Jack Chin and Carissa Hessick), NYU Press (2014). Measuring State-Created Immigration Climate (invited), with Pham Hoang Van, in How to Measure Immigration Policies?, Migration and Citizenship Newsletter of the American Political Science Association (2013). The Economic Impact of Local Immigration Regulation: An Empirical Analysis, with Pham Hoang Van, 32 CARDOZO LAW REVIEW 485 (2010) ● Reprinted in the Immigration and Nationality Law Review (William S. Hein & Co. Publishers) (republishing immigration law review articles “selected for their excellence”). ● Cited by Ezra Klein’s Economic and Domestic Policy Blog, “Does Restricting Immigration Affect Economic Performance?” WASHINGTON POST (Aug. 5, 2010) When Immigration Borders Move, 61 FLORIDA LAW REVIEW 1115 (2009) ● Required reading for “The Rights of Noncitizens” seminar, Northeastern University School of Law, Professor Rachel E. -

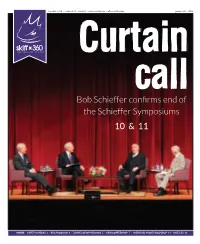

Bob Schieffer Confirms End of the Schieffer Symposiums 10 & 11

the skiff x 360 . volume 114 . issue 19 . www.tcu360.com . all tcu. all the time. january 28 · 2016 ski x 360 T H E S K I F F B Y T C U 3 6 0 Curtain call Bob Schieffer confirms end of the Schieffer Symposiums 10 & 11 INSIDE : SAFETY CHECKS 2 - REC PROGRAM 4 - TUNNEL OF OPPRESSION 5 - NEW COFFEESHOP 7 - WEEKEND SPORTS ROUNDUP 11 - PUZZLES 14 2 skiff x 360 · www.tcu360.com all tcu. all the time. january 28 · 2016 campus life riff ram, instagram! Holiday break safety checks result in alcohol violations By Zoe Zabel [email protected] Several TCU students were issued alcohol violations over holiday break after alcohol was discovered in their dorm rooms during safety checks. More than a dozen violations for alcohol possession were issued over the break, said Craig Allen, the director @TCU_VOLLEYBALL of housing and residence life. TCU VOLLEYBALL The volleyball team welcomed team member Anna Walsh with an Instagram post. To see Maggie Cohen, a sophomore, said she and her your picture featured, hashtag your photo #skiffx360. suite-mates were issued violations after empty wine bottles were found. The Skiff by TCU360 “We had wine in our room leftover in the trash can,” TCU Box 298050 Cohen said. Allen said alcohol violations can be issued even when Fort Worth, TX 76129 students are not present. [email protected] “If you’re not 21, then it’s against the law to have alcohol in your room,” Allen said. “If we happen to see Phone (817) 257-3600, Fax (817) 257-7133 it when we enter a room, we aren’t going to ignore a Skiff Editor: Jocelyn Sitton violation of Texas state law.” He said students can talk to their hall directors for Associate Editor: Victoria Knox guidance if they are held responsible for committing a Design Editor: Malia Buthe violation. -

Free Will Is No Bargain: How Misunderstanding Human Behavior Negatively Influences Our Criminal Justice System

FREE WILL IS NO BARGAIN: HOW MISUNDERSTANDING HUMAN BEHAVIOR NEGATIVELY INFLUENCES OUR CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM Sean Daly* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 992 I. DO YOU CHOOSE TO THINK WHAT YOU THINK? ............................... 994 A. The Definition of Free Will ......................................................... 994 B. The Principal Philosophical Positions on Free Will .................. 996 C. The Objective Argument: Your Brain is the Boss ....................... 998 D. The Subjective Argument: Witnessing Your Experience ........... 1001 II. FREE WILL AND THE LAW ................................................................. 1003 A. Legal Recognition of Free Will ................................................. 1003 B. The Blame Game ....................................................................... 1008 C. Retribution and Legal Punishments .......................................... 1013 D. The Precarious Punishment of Retribution in Action ............... 1016 III. A WORLD WITHOUT FREE WILL ...................................................... 1021 A. Could We Still Adequately Punish Criminals? ......................... 1021 B. How Much Would Have to Change? ......................................... 1025 CONCLUSION ................................................................................................ 1029 INTRODUCTION After Wilbur was found guilty, there was no questioning his immediate fu- ture. The executioner -

Wiseyes LLC [email protected] Title: Listen to Your Intuition and Avoid Making Mistakes Free! Introductory Offer 3 Pages: 245

Wiseyes LLC [email protected] Title: Listen To Your Intuition And Avoid Making Mistakes Free! Introductory offer 3 Pages: 245 Language: English Non-Fiction Categories: How To * Self Help * True Crime * Entertainment * Pop Culture * Dating/Relationships * Current Affairs * Pets * Women’s Issues * Health * Social Issues * Parenting * Description: 21st century street smart survival skills. Grooming your offspring to successful navigate safely away from home. 1 Wiseyes LLC Series pre-publishing peek! Entertaining * Educational * Empowering * Enlightening * Introductory Offer: 3 free! EBooks Listen to your intuition and avoid making mistakes Series 1: Research Before Romance Or Finance *Listen to your intuition and avoid making mistakes *Do your homework! *The dark side of silence Series 2: Fight Or Flight? *Securing your home *Know when and how to break up *Happily ever after requires communication Series 3: What Are You Bringing To The Table? *Body image 1 *How well do you really know you? *Love, money & independence Series 4: Fatal Flaws *Familiarity *What/who are you attracting into your life? *Deal breakers/Red Flags that shouldn’t be ignored 2 Kitchen Table Politics: Including Your Kids In The Conversation Nourishing bodies and mind October 2016 Toledo Parent I love my kitchen table. A few friends of mine made it out of wood left over from the repairs the front porch of our old house. It’s one of those “trendy” farm style tables, but it was also quite cheap because it was repurposed from an intense building project. It seats 8-10 people and will be in our house for a long, long time. Recently, my wife and I have been thinking about the role his table plays in our kids’ lives.