Development of Community Institutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune Effectiveness Prepared for United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mali Mission, Democracy and Governance (DG) Team Prepared by Dr. Lynette Wood, Team Leader Leslie Fox, Senior Democracy and Governance Specialist ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Third Floor Burlington, VT 05401 USA Telephone: (802) 658-3890 FAX: (802) 658-4247 in cooperation with Bakary Doumbia, Survey and Data Management Specialist InfoStat, Bamako, Mali under the USAID Broadening Access and Strengthening Input Market Systems (BASIS) indefinite quantity contract November 2000 Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS.......................................................................... i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................... ii 1 INDICATORS OF AN EFFECTIVE COMMUNE............................................... 1 1.1 THE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE..............................................1 1.2 THE EFFECTIVE COMMUNE: A DEVELOPMENT HYPOTHESIS..........................................2 1.2.1 The Development Problem: The Sound of One Hand Clapping ............................ 3 1.3 THE STRATEGIC GOAL – THE COMMUNE AS AN EFFECTIVE ARENA OF DEMOCRATIC LOCAL GOVERNANCE ............................................................................4 1.3.1 The Logic Underlying the Strategic Goal........................................................... 4 1.3.2 Illustrative Indicators: Measuring Performance at the -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

Régions De SEGOU Et MOPTI République Du Mali P! !

Régions de SEGOU et MOPTI République du Mali P! ! Tin Aicha Minkiri Essakane TOMBOUCTOUC! Madiakoye o Carte de la ville de Ségou M'Bouna Bintagoungou Bourem-Inaly Adarmalane Toya ! Aglal Razelma Kel Tachaharte Hangabera Douekiré ! Hel Check Hamed Garbakoira Gargando Dangha Kanèye Kel Mahla P! Doukouria Tinguéréguif Gari Goundam Arham Kondi Kirchamba o Bourem Sidi Amar ! Lerneb ! Tienkour Chichane Ouest ! ! DiréP Berabiché Haib ! ! Peulguelgobe Daka Ali Tonka Tindirma Saréyamou Adiora Daka Salakoira Sonima Banikane ! ! Daka Fifo Tondidarou Ouro ! ! Foulanes NiafounkoéP! Tingoura ! Soumpi Bambara-Maoude Kel Hassia Saraferé Gossi ! Koumaïra ! Kanioumé Dianké ! Leré Ikawalatenes Kormou © OpenStreetMap (and) contributors, CC-BY-SA N'Gorkou N'Gouma Inadiatafane Sah ! ! Iforgas Mohamed MAURITANIE Diabata Ambiri-Habe ! Akotaf Oska Gathi-Loumo ! ! Agawelene ! ! ! ! Nourani Oullad Mellouk Guirel Boua Moussoulé ! Mame-Yadass ! Korientzé Samanko ! Fraction Lalladji P! Guidio-Saré Youwarou ! Diona ! N'Daki Tanal Gueneibé Nampala Hombori ! ! Sendegué Zoumané Banguita Kikara o ! ! Diaweli Dogo Kérengo ! P! ! Sabary Boré Nokara ! Deberé Dallah Boulel Boni Kérena Dialloubé Pétaka ! ! Rekerkaye DouentzaP! o Boumboum ! Borko Semmi Konna Togueré-Coumbé ! Dogani-Beré Dagabory ! Dianwely-Maoundé ! ! Boudjiguiré Tongo-Tongo ! Djoundjileré ! Akor ! Dioura Diamabacourou Dionki Boundou-Herou Mabrouck Kebé ! Kargue Dogofryba K12 Sokora Deh Sokolo Damada Berdosso Sampara Kendé ! Diabaly Kendié Mondoro-Habe Kobou Sougui Manaco Deguéré Guiré ! ! Kadial ! Diondori -

Mission De Suivi Physique Et Financier Des Projets Et Programmes D’Investissements Publics Dans Les Regions De Segou, Mopti Et Sikasso

MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE République du Mali ET DES FINANCES Un Peuple-Un But-Une Foi =-=-= -=-=-=-=-=--= DIRECTION NATIONALE DE LA PLANIFICATION DU DEVELOPPEMENT MISSION DE SUIVI PHYSIQUE ET FINANCIER DES PROJETS ET PROGRAMMES D’INVESTISSEMENTS PUBLICS DANS LES REGIONS DE SEGOU, MOPTI ET SIKASSO Décembre 2018 1 TABLE DES MATIERES Introduction........................................................................................................................................................3 I - DEROULEMENT DE LA MISSION..........................................................................................................5 A. REGION DE SEGOU...............................................................................................................................5 1. Contrat Plan Etat/Office Riz Segou/Producteurs..............................................................................5 A- REGION DE MOPTI ...............................................................................................................................8 1. Programme d’Urgence pour la Relance du Développement des Régions du Nord (PURD/RN) / Région de Mopti .........................................................................................................................................8 B. REGION DE SIKASSO .........................................................................................................................13 1. Projet de Formation Professionnelle, Insertion et appui à l'Entreprenariat des Jeunes Ruraux (FIER) .............................................................................................................................................13 -

Armee De L'air N° Code Nina Prenoms Nom Sexe Prenoms Pere Prenoms Mere Nom Mere Date De Naissance Lieu Naissance Vague Localit

ARMEE DE L'AIR N° CODE NINA PRENOMS NOM SEXE PRENOMS_PERE PRENOMS_MERE NOM_MERE DATE_DE_NAISSANCE LIEU_NAISSANCE VAGUE LOCALITÉ 1 002 19609105008266R OUMAR DIAWARA M BACOU ASTAN DEMBELE 15/04/1996 SABALIBOUGOU VAGUE 01 BAMAKO 2 004 19803133001200J ABDOULAYE DIABATE M BAKARY MINATA KOUYATE 24/02/1998 NIENA VAGUE 01 BAMAKO 3 006 19603501008063C ABDOULAYE KONE M ABOUBACAR MINATA DIARRA 24/02/1996 KOULOUKORO VAGUE 01 BAMAKO 4 007 29809103019077L KADIATOU SOUSANE KONE F SEKO MARIAM DIALLO 29/01/1998 OUOLOFOBOUGOU BOLIBANA VAGUE 01 BAMAKO 5 008 19702501002010X OUMAR MAIGA M MALICK WARAKATA MAIGA 19/05/1997 CAMP-MILITAIRE VAGUE 01 BAMAKO 6 009 29909101003299F AMINATA TRAORE F BOCAR NIAMEY KONATE 15/05/1999 DIELIBOUGOU VAGUE 01 BAMAKO 7 0010 10009104002B29L YAYA FOFANA M FAMOUSSA ASSITAN TRAORE 31/12/2000 DJIKORONI PARA VAGUE 01 BAMAKO 8 0011 299CI901058005L AWA KONE F BIRAMA SALIMATA TOURE 17/05/1999 GUITRY VAGUE 01 BAMAKO 9 0013 10002512001019H BAYE KEITA M MOUSSA AWA COULIBALY 15/09/2000 DOGODOUMAN VAGUE 01 BAMAKO 10 0014 29802501009105D AFFOU MANANZA KONE F BIRAMA NIELE TRAORE 23/03/1998 KOKO VAGUE 01 BAMAKO 11 0016 29902501008067K SARAN KONE F ABDOULAYE AWA KONE 20/10/1999 KATI KORO VAGUE 01 BAMAKO 12 0018 19509104007240T SEKOU SOGORE M KANIBOUKARY SOUMBA SOGORE 12/06/1995 SEBENINKORO VAGUE 01 BAMAKO 13 0019 19809104005045F SAIDE ASHARIFF DIAKITE M FOUSSEYNI BAGUISSA KOUYATE 02/10/1998 LAFIABOUGOU VAGUE 01 BAMAKO 14 0021 19809103020002Y KARIM TRAORE M BRAHIMA MINATA TRAORE 07/11/1998 POINT G VAGUE 01 BAMAKO 15 0022 19709106006091J ALASSANE -

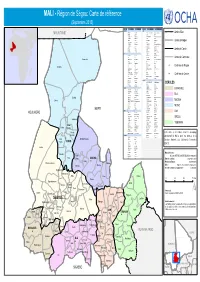

MALI - REGION DE SEGOU Cercle De Ségou - Carte De Référence

MALI - REGION DE SEGOU Cercle de Ségou - Carte de référence .! Tantani ! ! Godji Tourela ! Godji-koro ! ! Tomono ! Daouna Niono Ouerde .! ! Sagala N'galamana (!!! Dianiguele Toban ! Macina Barambiela .! ! Diedougou Boureme Were Fabougou Camp Peulh ! ! Doura ! ! Baya Were (!! ! Toima ! ! Markabougou Fraction Akotef Fabougou ! ! ! ! M'pewanicoura Lamini Were Ndianabougou ! ! Diawere Tossouma N'dotila ! ! Sissako ! Yebougou Kango ! Sangolola ! Zafina ! Bodjana ! ! ! Nehou Niampiena Were Niougou Sanamadougou Marka ! Dougabougou Koroni ! ! ! ! Torola Chokoun Niampiena ! ! ! Kolobele !! Dona Tountouroubala ! Rozodaka ! ! Dionkebougou ! Diassa ! ! Senekou Markani-were Dougabougou Sinka Were ! ! Dongoma ! Mieou ! ! Sabalibougou ! Balle Banougou (! ! ! Flawere ! ! Kayeka Dagua Fonona ! Sonogo Missiribougou ! Nierila! ! ! ! ! Diado !Chiemmou Dola Ngolobabougou Moctar-were ! ! Diessourna Teguena ! Banga Boumboukoro ! Saou ! Barkabougou ! Sibila ! ! ! ! N'tikithiona ! Gawatou ! (!! Diarrabougou ! ! Niadougou Tinigola Thiongo ! ! Founebougou Soualibougou N'diebougou Babougou-koroni ! N'gabakoro Adama-were Ndofinena ! ! ! Zaman Were ! ! ! ! ! Dianabougou Kationa ! Ladji-were Campement Tilwate ! ! Point A ! Drissa Were Koro ! ! ! Dlaba Banna! ! ! Welintiguila Bozo ! ! ! ! ! !! ! Gomabougou Zorokoro-were ! ! Sorona Temou ! Soungo ! Babougou ! Foba Sosse Bamanan Zoumana-were !! Daouna Thin Dialakoro ! ! ! ! Boureima-were ! ! M'balibougou Thio (! Sansanding Sama ! ! Djibougou ! ! Songolon ! Diao - Were Falinta ! Sarkala-were ! Gomakoro ! Nakoro Nonongo -

Région De Segou-Mali

! ! ! RÉGION DE SEGOU - MALI ! Map No: MLIADM22304 7°0'W 6°0'W 5°0'W 4°0'W M A U R I T A N I E !Ambiri-Habe Tissit ! CER CLE S E T CO M MU NE S D E SÉ GO U ! Enghem ! Nourani ! Gathi-Loumo ! Boua Moussoule SÉGOU BLA El Massouka 30 Communes 17 Communes ! ! Korientzé RÉGION DE SÉGOU Kolima ! ! Fani ! ! BellenYouwarou ! ! Guidio-Saré Kazangasso Koulandougou Sansanding ! ! Togou Touna ! P Chef-lieu Région Route Principale ! Dougabougou ! Korodougou Boussin Diena ! Diona Yangasso ! ! Chef-lieu Cercle Route Secondaire ! ! Sibila ! ! ! Tiemena Kemeni Gueneibé Zoumane ! ! ! Nampala NKoumandougou !Sendegué ! ! Farakou Massa Niala Dougouolo Chef-lieu Commune Piste ! ! ! ! Dioro ! ! ! ! ! Samabogo ! Boumodi Magnale Baguindabougou Beguene ! ! ! Dianweli ! ! ! Kamiandougou Village Frontière Internationale Bouleli Markala ! Toladji ! ! Diédougou 7 ! Diganibougou ! Falo ! Tintirabe ! ! Diaramana ! Fatine Limite Région ! ! Aéroport/Aérodrome Souba ! Belel !Dogo ! ! ! Diouna 7 ! Sama Foulala Somasso ! Nara ! Katiéna Farako ! Limite Cercle ! Cinzana N'gara ! Bla Lac ! ! Fleuve Konodimini ! ! Pelengana Boré Zone Marécageuse Massala Ségou Forêts Classées/Réserves Sébougou Saminé Soignébougou Sakoiba MACINA 11 Communes Monimpébougou ! N Dialloubé N ' ! ' 0 0 ° ° 5 C!ette carte a été réalisée selon le découpage administratif du Mali à partir des SAN 5 1 doGnnoéuems bdoe ula Direction Nationale des Collectivités Territoriales (DNCT). N I O N O 25 Communes Macina 1 Kokry Centre !Borko ! Sources: ! Souleye ! ! Konna Boky Were ! ! - Direction Nationale des Collectivités -

Baseline Study Report

“Support for Quality and Equity in Education” SUPPORT PROGRAM FOR THE MINISTRY It OF NATIONAL EDUCATION BASELINE STUDY REPORT OF THE “SUPPORT FOR QUALITY AND EQUITY IN EDUCATION” PROGRAM January 2004 Baseline Survey Report of the “Support for Quality and Equity in Education” Program --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Table of Contents ACRONYM LIST ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................................................................................. 4 I. INTRODUCTION …………………………………………..……………...…..5 I.1 - Context ............................................................................................................................... 5 I.2 – Review of the overall program strategy.......................................................................... 5 I.3 – Global Objective of the Baseline Survey ........................................................................ 5 II – METHODOLOGY.......................................................................................................... 6 II.1 – Levels of investigation..................................................................................................... 6 II.2 – Units selected and surveyed............................................................................................ 6 II.3 – Design and testing of questionnaires ............................................................................. 7 II.3.1 – CAP questionnaire..................................................................................................................................7 -

Mli0003 Ref Region De Segou A3 09092013

MALI - Région de Ségou: Carte de référence (Septembre 2013) CERCLE COMMUNE CHEF LIEU CERCLE COMMUNE CHEF LIEU BARAOUELI SAN BARAOUELI Baraouéli BARAMANDOUGOU Baramandougou Limite d'Etat MAURITANIE BOIDIE Boidié DAH Dah DOUGOUFIE Dougoufié DIAKOUROUNA Diakourouna Nerissso GOUENDO Gouendo DIELI Diéli KALAKE Kalaké DJEGUENA Djéguena Limite de Région KONOBOUGOU Konobougou FION Fion N'GASSOLA N'Gassola KANIEGUE Dioundiou Konkankan SANANDO Sanando KARABA Karaba Kagoua SOMO Somo KASSOROLA Nianaso TAMANI Tamani KAVA Kimparana Limite de Cercle TESSERELA Tesserla MORIBILA Moribila‐Kagoua BLA N'GOA N'Goa BENGUENE Beguené NIAMANA Niamana Sobala BLA Bla NIASSO Niasso Limite de Commune Nampalari DIARAMANA Diaramana N'TOROSSO N'Torosso Bolokalasso DIENA Diéna OUOLON Ouolon DOUGOUOLO Dougouolo SAN San FALO Falo SIADOUGOU Siélla .! Chef-lieu de Région Dogofry FANI Fani SOMO Somo KAZANGASSO Kazangasso SOUROUNTOUNA Sourountouna KEMENI Kémeni SY Sy KORODOUGOU Nampasso TENE Tené ! KOULANDOUGOU N'Toba TENENI Ténéni Chef-lieu de Cercle NIALA Niala TOURAKOLOMBA Toura‐Kalanga SAMABOGO Samabogo WAKY Waki1 SOMASSO Somasso SEGOU TIEMENA Tiémena BAGUIDADOUGOU Markanibougou TOUNA Touna BELLEN Sagala CERCLES YANGASSO Yangasso BOUSSIN Boussin MACINA CINZANA Cinzana Gare BOKY WERE Boky‐Weré DIGANIBOUGOU Digani BARAOUELI FOLOMANA Folomana DIORO Dioro KOKRY Kokry‐Centre DIOUNA Diouna KOLONGO Kolongotomo DJEDOUGOU Yolo BLA Diabaly MACINA Macina DOUGABOUGOU Dougabougou Koroni MATOMO Matomo‐Marka FARAKO Farako Sokolo MONIMPEBOUGOU Monimpébougou FARAKOU MASSA Kominé MACINA -

Journal Officiel De La Republique Du Mali

842 JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE DU MALI DECRET N°06-252/P-RM DU 13 JUIN 2006 DETERMINANT LE CADRE ORGANIQUE DES SERVICES REGIONAUX ET SUB-REGIONAUX DE LA DIRECTION NATIONALE DE LA PECHE LE PRESIDENT DE LA REPUBLIQUE, Vu la Constitution ; Vu la Loi N°94-009 du 22 mars 1994 portant principes fondamentaux de la création, de l’organisation, de la gestion et du contrôle des services publics modifiée , par la loi N°02-048 du 22 juillet 2002 ; Vu la Loi N°05-009 du 11 février 2005 portant création de la Direction Nationale de la Pêche ; Vu le Décret N°179 / PG-RM du 23 juillet 1985 fixant les conditions et procédures d’élaboration et de gestion des cadres organiques ; Vu le décret N°204/PG-RM du 21 août 1985 déterminant les modalités de gestion et de contrôle des structures des services publics ; Vu le Décret N°05-102/P-RM du 9 mars 2005 fixant l’organisation et les modalités de fonctionnement de la Direction Nationale de la Pêche ; Vu le Décret N°04-140/P-RM du 29 avril 2004 portant nomination du Premier Ministre ; Vu le Décret N°04-141/P-RM du 02 mai 2004 modifié, portant nomination des membres du Gouvernement ; Vu le Décret N°04-146/P-RM du 13 mai 2004 fixant les intérims des membres du Gouvernement ; STATUANT EN CONSEIL DES MINISTRES, DECRETE ARTICLE 1ER : Le cadre organique (structures et effectifs) des services régionaux et subrégionaux de la Direction Nationale de la Pêche est défini et arrêté comme suit : 1. -

Liste Des Admis

DEF 2017 AE-SEGOU MINISTERE DE L'EDUCATION NATIONALE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ------------------ Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi ACADEMIE D'ENSEIGNEMENT DE SEGOU ------------------ ------------------ OPTION CLASSIQUE CENTRE D'ANIMATION PEDAGOGIQUE DE FARAKO N° STATUT PRENOMS NOM DATE NAISS SEXE ECOLE CENTRE EXAM PLACE ELEVE 881 Alou BOUARE 01/01/2000 M REG DIGANI 2°C DIGANI 1°C 940 Bouba BOUARE 04/04/2000 M REG DIGANI 2°C DIGANI 1°C 1126 Oumar BOUARE 01/01/2000 M REG DIGANI 2°C DIGANI 1°C 1766 Aboubacar COULIBALY 01/01/2002 M REG DIGANI 2°C DIGANI 1°C 2125 Bakary COULIBALY 01/02/1996 M CL CL DIGANI 1°C 2130 Bakary COULIBALY 01/01/2000 M REG DIGANI 2°C DIGANI 1°C 2144 Bakary a COULIBALY 01/01/2001 M REG DIGANI 2°C DIGANI 1°C 2327 Daouda COULIBALY 20/06/2003 M REG DIGANI 2°C DIGANI 1°C 3943 Kadia COUMARE 12/04/1997 F CL CL DIGANI 1°C 6660 Dramane DIARRA 31/12/2002 M REG DIGANI 2°C DIGANI 1°C 9621 Abdoulaye KANE 24/06/1999 M REG DIGANI 2°C DIGANI 1°C 13215 N'faly SAMAKE 07/06/1990 M CL CL DIGANI 1°C 17598 Moussa TRAORE 01/01/2000 M REG DIGANI 2°C DIGANI 1°C 951 Daouda BOUARE 01/01/2002 M REG MARKANIBOUGOU 2°C DOURA 1°C 972 Drissa BOUARE 08/08/1997 M CL CL DOURA 1°C 1814 Adama COULIBALY 30/03/2000 M REG SAGALA 2°C DOURA 1°C 1913 Aly COULIBALY 24/12/1999 M REG MARKANIBOUGOU 2°C DOURA 1°C 1941 Amady COULIBALY 18/11/2000 M REG SAGALA 2°C DOURA 1°C 2822 Kassim COULIBALY 01/01/2001 M REG DOURA 2°C DOURA 1°C 3024 Makary COULIBALY 05/07/2000 M REG SAGALA 2°C DOURA 1°C 3078 Mami COULIBALY 01/01/2000 M REG MARKANIBOUGOU 2°C DOURA 1°C Page 1 de 10 DEF 2017 -

Arrêt Portant Liste Définitive Des Candidats Du 1 Er Tour De La

COUR CONSTITUTIONNELLE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ---------------- Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi --------------- ARRET N°2018-02/CC-EP DU 04 JUILLET 2018 PORTANT LISTE DEFINITIVE DES CANDIDATS A L’ELECTION DU PRESIDENT DE LA REPUBLIQUE (Scrutin du 29 juillet 2018) La Cour constitutionnelle Vu la Constitution ; Vu la Loi n°97-010 du 11 février 1997 modifiée par la Loi n°02-011 du 5 mars 2002 portant loi organique déterminant les règles d'organisation et de fonctionnement de la Cour constitutionnelle ainsi que la procédure suivie devant elle ; Vu la Loi n°2016-048 du 17 octobre 2016 modifiée par la Loi n°2018- 014 du 23 avril 2018 portant loi électorale ; Vu la Loi n°64-21/AN-RM du 15 juillet 1964 déterminant les modalités de légalisation en République du Mali ; Vu la Loi n°017-2012 du 31 janvier 2012 portant création de onze (11) nouvelles régions ; Vu le Décret n°02-119/P-RM du 08 mars 2002 fixant le modèle de déclaration de candidature à l'élection du Président de la République; Vu le Décret n°06-568/P-RM du 29 décembre 2006 fixant les modalités d'application du soutien aux candidats à l'élection du Président de la République ; Vu le Décret n°2018-0398/P-RM du 27 avril 2018 portant convocation du collège électoral, ouverture et clôture de la campagne électorale à l'occasion de l'élection du Président de la République ; Vu le Règlement Intérieur de la Cour constitutionnelle en date du 28 août 2002 ; Vu la décision n°2018-0076/P-CCM du 29 mai 2018 de Madame le Président de la Cour constitutionnelle portant création d’une Commission de réception