Bozovic for Ginzburg Text+Figs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nobel Prize Sweden.Se

Facts about Sweden: The Nobel Prize sweden.se The Nobel Prize – the award that captures the world’s attention The Nobel Prize is considered the most prestigious award in the world. Prize- winning discoveries include X-rays, radioactivity and penicillin. Peace Laureates include Nelson Mandela and the 14th Dalai Lama. Nobel Laureates in Literature, including Gabriel García Márquez and Doris Lessing, have thrilled readers with works such as 'One Hundred Years of Solitude' and 'The Grass is Singing'. Every year in early October, the world turns Nobel Day is 10 December. For the prize its gaze towards Sweden and Norway as the winners, it is the crowning point of a week Nobel Laureates are announced in Stockholm of speeches, conferences and receptions. and Oslo. Millions of people visit the website At the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in of the Nobel Foundation during this time. Stockholm on that day, the Laureates in The Nobel Prize has been awarded to Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, people and organisations every year since and Literature receive a medal from the 1901 (with a few exceptions such as during King of Sweden, as well as a diploma and The Nobel Banquet is World War II) for achievements in physics, a cash award. The ceremony is followed a magnificent party held chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature by a gala banquet. The Nobel Peace Prize at Stockholm City Hall. and peace. is awarded in Oslo the same day. Photo: Henrik Montgomery/TT Henrik Photo: Facts about Sweden: The Nobel Prize sweden.se Prize in Economic Sciences prize ceremonies. -

Nobel Week Stockholm 2018 – Detailed Information for the Media

Nobel Week Stockholm • 2018 Detailed information for the media December 5, 2018 Content The 2018 Nobel Laureates 3 The 2018 Nobel Week 6 Press Conferences 6 Nobel Lectures 8 Nobel Prize Concert 9 Nobel Day at the Nobel Museum 9 Nobel Week Dialogue – Water Matters 10 The Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in Stockholm 12 Presentation Speeches 12 Musical Interludes 13 This Year’s Floral Decorations, Concert Hall 13 The Nobel Banquet in Stockholm 14 Divertissement 16 This Year’s Floral Decorations, City Hall 20 Speeches of Thanks 20 End of the Evening 20 Nobel Diplomas and Medals 21 Previous Nobel Laureates 21 The Nobel Week Concludes 22 Follow the Nobel Prize 24 The Nobel Prize Digital Channels 24 Nobelprize org 24 Broadcasts on SVT 25 International Distribution of the Programmes 25 The Nobel Museum and the Nobel Center 25 Historical Background 27 Preliminary Timetable for the 2018 Nobel Prize Award Ceremony 30 Seating Plan on the Stage, 2018 Nobel Prize Award Ceremony 32 Preliminary Time Schedule for the 2018 Nobel Banquet 34 Seating Plan for the 2018 Nobel Banquet, City Hall 35 Contact Details 36 the nobel prize 2 press MeMo 2018 The 2018 Nobel Laureates The 2018 Laureates are 12 in number, including Denis Mukwege and Nadia Murad, who have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize Since 1901, the Nobel Prize has been awarded 590 times to 935 Laureates Because some have been awarded the prize twice, a total of 904 individuals and 24 organisations have received a Nobel Prize or the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel -

The Nobel Prize Sweden.Se

Facts about Sweden: The Nobel Prize sweden.se The Nobel Prize – the award that captures the world’s attention The Nobel Prize is considered the most prestigious award in the world. Prize- winning discoveries include X-rays, radioactivity and penicillin. Peace Laureates include Nelson Mandela and the 14th Dalai Lama. Nobel Laureates in Literature, including Gabriel García Márquez and Doris Lessing, have thrilled readers with works such as 'One Hundred Years of Solitude' and 'The Grass is Singing'. Every year in early October, the world turns Nobel Day is 10 December. For the prize its gaze towards Sweden and Norway as the winners, it is the crowning point of a week Nobel Laureates are announced in Stockholm of speeches, conferences and receptions. and Oslo. Millions of people visit the website At the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in of the Nobel Foundation during this time. Stockholm on that day, the Laureates in The Nobel Prize has been awarded to Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, people and organisations every year since and Literature receive a medal from the 1901 (with a few exceptions such as during King of Sweden, as well as a diploma and The Nobel Banquet is World War II) for achievements in physics, a cash award. The ceremony is followed a magnificent party held chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature by a gala banquet. The Nobel Peace Prize at Stockholm City Hall. and peace. is awarded in Oslo the same day. Photo: Henrik Montgomery/TT Henrik Photo: Facts about Sweden: The Nobel Prize sweden.se Prize in Economic Sciences prize ceremonies. -

Table of Contents

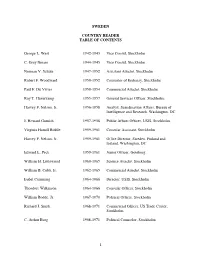

SWEDEN COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS George L. West 1942-1943 Vice Consul, Stockholm C. Gray Bream 1944-1945 Vice Consul, Stockholm Norman V. Schute 1947-1952 Assistant Attaché, Stockholm Robert F. Woodward 1950-1952 Counselor of Embassy, Stockholm Paul F. Du Vivier 1950-1954 Commercial Attaché, Stockholm Roy T. Haverkamp 1955-1957 General Services Officer, Stockholm Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1956-1958 Analyst, Scandinavian Affairs, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington, DC J. Howard Garnish 1957-1958 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Stockholm Virginia Hamill Biddle 1959-1961 Consular Assistant, Stockholm Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1959-1961 Office Director, Sweden, Finland and Iceland, Washington, DC Edward L. Peck 1959-1961 Junior Officer, Goteborg William H. Littlewood 1960-1965 Science Attaché, Stockholm William B. Cobb, Jr. 1962-1965 Commercial Attaché, Stockholm Isabel Cumming 1964-1966 Director, USIS, Stockholm Theodore Wilkinson 1964-1966 Consular Officer, Stockholm William Bodde, Jr. 1967-1970 Political Officer, Stockholm Richard J. Smith 1968-1971 Commercial Officer, US Trade Center, Stockholm C. Arthur Borg 1968-1971 Political Counselor, Stockholm 1 Haven N. Webb 1969-1971 Analyst, Western Europe, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington, DC Patrick E. Nieburg 1969-1972 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Stockholm Gerald Michael Bache 1969-1973 Economic Officer, Stockholm Eric Fleisher 1969-1974 Desk Officer, Scandinavian Countries, USIA, Washington, DC William Bodde, Jr. 1970-1972 Desk Officer, Sweden, Washington, DC Arthur Joseph Olsen 1971-1974 Political Counselor, Stockholm John P. Owens 1972-1974 Desk Officer, Sweden, Washington, DC James O’Brien Howard 1972-1977 Agricultural Officer, US Department of Agriculture, Stockholm John P. Owens 1974-1976 Political Officer, Stockholm Eric Fleisher 1974-1977 Press Attaché, USIS, Stockholm David S. -

Nobel Foundation 21 July 2020

Nobel Prize banquet cancelled over coronavirus: Nobel Foundation 21 July 2020 The lavish Nobel Banquet traditionally marks the end of the so-called Nobel Week in December, when the year's prize winners are invited to Stockholm for talks and the award ceremony. Housed in Stockholm's City Hall, the winners, together with the Swedish royal family and some 1,300 guests are treated to a multi-course dinner and entertainment. The winners, with the exception of the Peace Prize laureates who are honoured in Oslo, also traditionally give a speech during this dinner. The announcement of the prizes (Medicine, Physics, Chemistry, Literature, Peace, then Economics) will still be held scheduled between 5 and 12 October, the Foundation adds. The award ceremonies in Stockholm and Oslo on December 10 will also be held in "new forms". Credit: Wikipedia The Nobel banquet was last cancelled in 1956 to avoid inviting the Soviet ambassador because of The Nobel Foundation, which manages the Nobel the repression of the Hungarian Revolution, a Prizes, on Tuesday cancelled its traditional Nobel Foundation spokeswoman said. December banquet due to the COVID-19 pandemic, though the award ceremonies will still The banquet was also cancelled during the two be held in "new forms". world wars, and in 1907 and 1924. This is the first time since 1956 that the banquet © 2020 AFP has been cancelled, according to the foundation. "The Nobel week will not be as it usually is due to the current pandemic. This is a very special year when everyone needs to make sacrifices and adapt to completely new circumstances," Lars Heikensten, director of the Nobel Foundation, said in a statement. -

Nobel Week Stockholm • 2018

Nobel Week Stockholm • 2018 Detailed information for the media December 5, 2018 Content The 2018 Nobel Laureates . 3 The 2018 Nobel Week . 6 Press Conferences . 6 Nobel Lectures . 8 Nobel Prize Concert . 9 Nobel Day at the Nobel Museum . 9 Nobel Week Dialogue – Water Matters . 10 The Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in Stockholm . 12 Presentation Speeches . 12 Musical Interludes . 13 This Year’s Floral Decorations, Concert Hall . 13 The Nobel Banquet in Stockholm . 14 Divertissement . 16 This Year’s Floral Decorations, City Hall . 20 Speeches of Thanks . 20 End of the Evening . 20 Nobel Diplomas and Medals . 21 Previous Nobel Laureates . 21 The Nobel Week Concludes . 22 Follow the Nobel Prize . 24 The Nobel Prize Digital Channels . 24 Nobelprize org. 24 Broadcasts on SVT . 25 International Distribution of the Programmes . 25 The Nobel Museum and the Nobel Center . 25 Historical Background . 27 Preliminary Timetable for the 2018 Nobel Prize Award Ceremony . 30 Seating Plan on the Stage, 2018 Nobel Prize Award Ceremony . 32 Preliminary Time Schedule for the 2018 Nobel Banquet . 34 Seating Plan for the 2018 Nobel Banquet, City Hall . 35 Contact Details . 36 the nobel prize 2 press MeMo 2018 The 2018 Nobel Laureates The 2018 Laureates are 12 in number, including Denis Mukwege and Nadia Murad, who have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize . Since 1901, the Nobel Prize has been awarded 590 times to 935 Laureates . Because some have been awarded the prize twice, a total of 904 individuals and 24 organisations have received a Nobel Prize or the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel . -

The Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prize The Nobel Prize is the first international award given yearly since 1901 for achievements in physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature and peace. Nobel Prize Facts 1901 – 2004 Total Science Prizes – 505 Physics: 172 Chemistry: 151 Physiology or Medicine: 182 Prizes are not awarded every year: 1940 – 1942: no prizes in any category were awarded Prize may be shared by up to three people Prize cannot be awarded posthumously Men:Women: 494:11 Mother-daughter winners: Curies (chemistry) Father-son: Siegbahn, Bohr, Bragg, Thomson (physics) Husband-wife: Curie (physics), Cori (physiology) Uncle-nephew: Chandrasakhar (physics) Brothers: Tinbergens (physiology, economics) Double winner/physics: Bardeen Double winner/chemistry: Sanger Double winner/different disciplines: Curie (physics, chemistry), Pauling (chemistry, peace) Country Physics Chemistry Medicine U.S. 66 47 90 Germany 27 26 18 Britain 21 23 20 France 11 7 9 USSR 6 1 2 Netherlands 6 2 3 Switzerland 4 5 -- Sweden 4 4 7 Austria 4 2 4 Canada 3 3 -- Denmark 3 1 6 Argentina -- 1 1 Belgium -- 1 2 Czechoslovakia -- 1 -- Italy 3 1 2 Japan 3 1 -- Finland -- 1 -- India 1 -- -- Mexico -- 1 -- Norway -- 1 -- Pakistan 1 -- -- South Africa -- 1 -- Australia -- -- 1 Hungary -- -- 1 Portugal -- -- 1 Spain -- -- 1 The Nobel Foundation The Nobel Foundation is a private institution established in 1900 based on the will of Alfred Nobel. The Foundation manages the assets made available through the will for the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, Literature and Peace. It represents the Nobel institutions externally and administers informational activities and arrangements surrounding the presentation of the Nobel Prize. -

Nobel Banquet Program

The Nobel Banquet 2018 The 2018 Nobel Laureates The Nobel Prize in Physics Dr Arthur Ashkin Professor Gérard Mourou Professor Donna Strickland The Nobel Prize in Chemistry Professor Frances H. Arnold Professor George P. Smith Sir Gregory P. Winter The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine Professor James P. Allison Professor Tasuku Honjo The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel Professor William D. Nordhaus Professor Paul M. Romer Programme Artistic Programme The guests of honour enter in procession PROGRAMME AND MUSIC BY Mikael Karlsson His Majesty’s toast is proposed by Professor Carl-Henrik Heldin, MUSIC AND LYRICS Anna von Hausswolff Chairman of the Board of the Nobel Foundation ORCHESTRATION Mikael Karlsson and Michael P. Atkinson A toast to Alfred Nobel’s memory is proposed by His Majesty the King CHOREOGRAPHER AND ARTISTIC DIRECTOR THE ROYAL SWEDISH BALLET Nicolas Le Riche Divertissement CONDUCTOR James Grossmith On Courage COSTUME DESIGNER FOR DANCERS Astrid Olsson H&M Act 1 Amends COSTUME DESIGNER FOR ANNA VON HAUSSWOLFF Helena Lundström Music by Mikael Karlsson and Anna von Hausswolff Vocals and lyrics by Anna von Hausswolff The Royal Swedish Opera The Royal Swedish Orchestra, the Royal Swedish Opera Chorus GENERAL MANAGER AND ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Birgitta Svendén Organ and piano Mikael Karlsson Act 2 Courage The Royal Swedish Orchestra Music by Mikael Karlsson and Anna von Hausswolff ORCHESTRA MANAGER Helle Solberg Vocals and lyrics by Anna von Hausswolff The Royal Swedish Orchestra CONCERTMASTER -

The Nobel Prize Sweden.Se

Facts about Sweden: The Nobel Prize sweden.se The Nobel Prize – the award that captures the world’s attention The Nobel Prize is considered the most prestigious award in the world. Prize- winning discoveries include X-rays, radioactivity and penicillin. Peace Laureates include Nelson Mandela and the 14th Dalai Lama. Nobel Laureates in Literature, including Gabriel García Márquez and Doris Lessing, have thrilled readers with works such as 'One Hundred Years of Solitude' and 'The Grass is Singing'. Every year in early October, the world turns Nobel Day is 10 December. For the prize its gaze towards Sweden and Norway as the winners, it is the crowning point of a week Nobel Laureates are announced in Stockholm of speeches, conferences and receptions. and Oslo. Millions of people visit the website At the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in of the Nobel Foundation during this time. Stockholm on that day, the Laureates in The Nobel Prize has been awarded to Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, people and organisations every year since and Literature receive a medal from the 1901 (with a few exceptions such as during King of Sweden, as well as a diploma and The Nobel Banquet is World War II) for achievements in physics, a cash award. The ceremony is followed a magnificent party held chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature by a gala banquet. The Nobel Peace Prize at Stockholm City Hall. and peace. is awarded in Oslo the same day. Photo: Henrik Montgomery/TT Henrik Photo: Facts about Sweden: The Nobel Prize sweden.se Prize in Economic Sciences ceremonies. -

The 2005 Nobel Festival in Stockholm

Press release, December 1, 2005 The 2005 Nobel Festival in Stockholm Soon it will again be time for the Nobel Festival to light up the winter darkness. In keeping with tradition, this year’s Nobel Prize Award Ceremony and Nobel Banquet in Stockholm will take place on December 10, as they have done with a few exceptions since 1901. The Nobel Peace Prize will be awarded the same day in Oslo. The Nobel Day will begin with the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall. The music in the program will be performed by the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of Danish-Italian conductor Giordano Bellincampi. In addition, acclaimed Swedish-American soprano soloist Erika Sunnergårdh will perform works by Puccini and Verdi. This year Ms. Sunnergårdh has appeared at venues in Sweden, Spain and elsewhere. During the spring of 2006 she will make her make her Metropolitan Opera debut in New York as Leonore in Fidelio. The floral decorations at the Prize Award Ceremony will be arranged by florist Helén Magnusson of Hässelby Blommor, who will adorn the Concert Hall stage in winter décor. After the ceremony comes the evening’s Nobel Banquet at the Stockholm City Hall. This year’s chefs are freelancer Marcus Aujalay, Torsten Kjörling of Hotel Tylösand and Håkan Thörnström of the Gothenburg restaurant Thörnströms Kök. In charge of dessert, in co- operation with Dessertakademien, are Magnus Johansson of KonditorSpecialisten and Ted Johansson of Lux Dessertchoklad. In the process of composing the menu, the chefs have worked together with a reference group consisting of chefs Gert Klötzke, Björn Halling and Fredrik Eriksson, who reveal that this year’s concept is characterized by Nordic winds. -

The Nobel Banquet 2016

The Nobel Banquet 2016 The 2016 Nobel Laureates The Nobel Prize in Physics Professor David J. Thouless Professor F. Duncan M. Haldane Professor J. Michael Kosterlitz The Nobel Prize in Chemistry Professor Jean-Pierre Sauvage Professor J. Fraser Stoddart Professor Bernard L. Feringa The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine Honorary Professor Yoshinori Ohsumi The Nobel Prize in Literature Mr Bob Dylan The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel Professor Oliver Hart Professor Bengt Holmström Programme Artistic Managers The guests of honour enter in procession P ROGRAMME BY His Majesty’s toast is proposed by Professor Carl-Henrik Heldin, Martin Fröst & Magnus Lindgren Chairman of the Board of the Nobel Foundation D IRECTOR A toast to Alfred Nobel’s memory is proposed by Linus Fellbom His Majesty the King T EXT Magnus Alkarp, Linus Fellbom and Martin Fröst D IVERTISSEMENT C HORAL D IRECTOR Karin Bäckström A journey through the evolution of music in three acts with C HOREOGRA P HER Martin Fröst & Magnus Lindgren Ambra Succi Swedish Chamber Orchestra The Adolf Fredrik Girls Choir A RTISTIC D IRECTOR OF THE S WE D ISH C HAMBER O RCHESTRA act 1 Gregor Zubicky Incantation by Anders Hillborg C OOR D INATOR Ancient suite: Hymns & O virtus sapiente by Mesomedes & Hildegaard von Bingen. Anna Claësson Transcribed, compilated and arranged by Jonas Forssell Presto from Concerto for Recorder, Traverse Flute, Strings and continuo in E minor by Georg Philipp Telemann. Arrangement Jonas Forssell Klezmer 2 by Göran Fröst Lighting -

Speeches by Nobel Laureates in the Sciences, 1901-2018

RESEARCH ARTICLE Give science and peace a chance: Speeches by Nobel laureates in the sciences, 1901-2018 ☯ ☯ ☯ Massimiano Bucchi , Enzo LonerID *, Eliana Fattorini Department of Sociology and Social Research, University of Trento, Trento, Italy ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] Abstract The paper presents the results of a quantitative analysis of speeches by Nobel laureates in a1111111111 a1111111111 the sciences (Physics, Chemistry, Medicine) at the Prize gala dinner throughout the whole a1111111111 history of the Prize, 1901±2018. The results outline key themes and historical trends. A a1111111111 dominant theme, common to most speeches, is the exaltation of science as a profession by a1111111111 the laureate. Since the 1970s, especially in chemistry, this element becomes more domain- specific and less related to science in general. One could speculate whether this happens chiefly in chemistry because its area of activity has been perceived to be at risk of erosion from competing fields (e.g. physics, biology). Over time, speeches become more technical, OPEN ACCESS less ceremonial and more lecture-oriented. Emphasis on broad, beneficial impact of science Citation: Bucchi M, Loner E, Fattorini E (2019) Give for humanity and mankind (as emphasised in Nobel's will) is more present in laureates' science and peace a chance: Speeches by Nobel speeches during the first half of the XXth century, while its relevance clearly declines during laureates in the sciences, 1901-2018. PLoS ONE the last decades. Politics and its relationship with science is also a relevant topic in Nobel 14(10): e0223505. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.