The Enigma of Digitized Property a Tribute to John Perry Barlow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leaving Reality Behind Etoy Vs Etoys Com Other Battles to Control Cyberspace By: Adam Wishart Regula Bochsler ISBN: 0066210763 See Detail of This Book on Amazon.Com

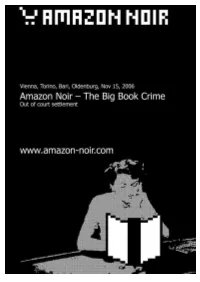

Leaving Reality Behind etoy vs eToys com other battles to control cyberspace By: Adam Wishart Regula Bochsler ISBN: 0066210763 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 discovering a new toy "The new artist protests, he no longer paints." -Dadaist artist Tristan Tzara, Zh, 1916 On the balmy evening of June 1, 1990, fleets of expensive cars pulled up outside the Zurich Opera House. Stepping out and passing through the pillared porticoes was a Who's Who of Swiss society-the head of state, national sports icons, former ministers and army generals-all of whom had come to celebrate the sixty-fifth birthday of Werner Spross, the owner of a huge horticultural business empire. As one of Zurich's wealthiest and best-connected men, it was perhaps fitting that 650 of his "close friends" had been invited to attend the event, a lavish banquet followed by a performance of Romeo and Juliet. Defiantly greeting the guests were 200 demonstrators standing in the square in front of the opera house. Mostly young, wearing scruffy clothes and sporting punky haircuts, they whistled and booed, angry that the opera house had been sold out, allowing itself for the first time to be taken over by a rich patron. They were also chanting slogans about the inequity of Swiss society and the wealth of Spross's guests. The glittering horde did its very best to ignore the disturbance. The protest had the added significance of being held on the tenth anniversary of the first spark of the city's most explosive youth revolt of recent years, The Movement. -

To Read John Perry's Full Introduction

John Perry Barlow, former Wyoming rancher, lyricist for the Grateful Dead, cofounder and vice-chair of the Electronic Frontier Foundation Following is John Perry Barlow's most excellent overview of the experience of the Sixties in his introduction t o Birth of a Psychedelic Culture: Conversations about Leary, the Harvard Experiments, Millbrook and the Sixties by Ram Dass and Ralph Metzner, with Gary Bravo Published by Synergetic Press http://www.synergeticpress.com/shop/birth-of-a- psychedelic-culture/ eBook now available. Foreword In the Beginning … by John Perry Barlow LSD is a drug that produces fear in people who don’t take it. Timothy Leary It’s now almost half a century since that day in September 1961 when a mysterious fellow named Michael Hollingshead made an appointment to meet Professor Timothy Leary over lunch at the Harvard Faculty Club. When they met in the foyer, Hollingshead was carrying with him a quart jar of sugar paste into which he had infused a gram of Sandoz LSD. He had smeared this goo all over his own increasingly abstract conscious- ness and it still contained, by his own reckoning, 4,975 strong (200 mcg) doses of LSD. And the mouth of that jar became perhaps the most sig- nificant of the fumaroles from which the ‘60s blew forth. Everybody who continues to obsess on the hilariously terrifying cultural epoch known as the ‘60s – which is to say, most everybody from “my ge- ge-generation,” the post-War demographic bulge that achieved perma- nent adolescence during that era – has his or her own sense of when the ‘60s really began. -

The Disappearance of Cyberspace and the Rise of Code

September 1998, Draft 3 Andrew L. Shapiro* The Disappearance of Cyberspace and the Rise of Code Imagine the emergence of a remarkable new communications technology. Using this tool, you can interact with anyone located anywhere in the world, provided they have the same minimal hardware that you have. You can stay informed, express yourself in ways never before imaginable, and get access to all the knowledge ever recorded by humankind. This technology fundamentally changes education, work, family life, entertainment, politics, and the economy. Still, it is fairly simple to use. Kids, in fact, will have an easier time than adults learning to use it. Once you get accustomed to using this technology, you'll wonder how you ever lived without it. No single person created this mode of communicating. Rather it developed spontaneously and collectively over time. And today, no single entity owns it or controls it, yet it works remarkably well. Most surprising of all, this innovation is thousands of years old. It is the alphabet. Coyness aside, it is useful to think about the alphabet as we consider the emergence of another communications technology, the Internet. In particular, this comparison will be fruitful as we consider the legal and political implications of the Internet -- or cyberspace, the "place" where online interactions are said to occur. We do not generally think of ourselves as having, or needing, a formal law of the alphabet. Similarly, I will argue here that we should think critically about what we mean when we speak of the “law of cyberspace.” To be sure, the increasing use of new technologies -- particularly a global, interactive, digital communications network such as the Internet -- can profoundly alter social relations. -

A Symposium for John Perry Barlow

DUKE LAW & TECHNOLOGY REVIEW Volume 18, Special Symposium Issue August 2019 Special Editor: James Boyle THE PAST AND FUTURE OF THE INTERNET: A Symposium for John Perry Barlow Duke University School of Law Duke Law and Technology Review Fall 2019–Spring 2020 Editor-in-Chief YOOJEONG JAYE HAN Managing Editor ROBERT HARTSMITH Chief Executive Editors MICHELLE JACKSON ELENA ‘ELLIE’ SCIALABBA Senior Research Editors JENNA MAZZELLA DALTON POWELL Special Projects Editor JOSEPH CAPUTO Technical Editor JEROME HUGHES Content Editors JOHN BALLETTA ROSHAN PATEL JACOB TAKA WALL ANN DU JASON WASSERMAN Staff Editors ARKADIY ‘DAVID’ ALOYTS ANDREW LINDSAY MOHAMED SATTI JONATHAN B. BASS LINDSAY MARTIN ANTHONY SEVERIN KEVIN CERGOL CHARLES MATULA LUCA TOMASI MICHAEL CHEN DANIEL MUNOZ EMILY TRIBULSKI YUNA CHOI TREVOR NICHOLS CHARLIE TRUSLOW TIM DILL ANDRES PACIUC JOHN W. TURANCHIK PERRY FELDMAN GERARDO PARRAGA MADELEINE WAMSLEY DENISE GO NEHAL PATEL SIQI WANG ZACHARY GRIFFIN MARQUIS J. PULLEN TITUS R. WILLIS CHARLES ‘CHASE’ HAMILTON ANDREA RODRIGUEZ BOUTROS ZIXUAN XIAO DAVID KIM ZAYNAB SALEM CARRIE YANG MAX KING SHAREEF M. SALFITY TOM YU SAMUEL LEWIS TIANYE ZHANG Journals Advisor Faculty Advisor Journals Coordinator JENNIFER BEHRENS JAMES BOYLE KRISTI KUMPOST TABLE OF CONTENTS Authors’ Biographies ................................................................................ i. John Perry Barlow Photograph ............................................................... vi. The Past and Future of the Internet: A Symposium for John Perry Barlow James Boyle -

You Might Be a Robot

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CRN\105-2\CRN203.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-MAY-20 13:27 YOU MIGHT BE A ROBOT Bryan Casey† & Mark A. Lemley‡ As robots and artificial intelligence (AI) increase their influ- ence over society, policymakers are increasingly regulating them. But to regulate these technologies, we first need to know what they are. And here we come to a problem. No one has been able to offer a decent definition of robots and AI—not even experts. What’s more, technological advances make it harder and harder each day to tell people from robots and robots from “dumb” machines. We have already seen disas- trous legal definitions written with one target in mind inadver- tently affecting others. In fact, if you are reading this you are (probably) not a robot, but certain laws might already treat you as one. Definitional challenges like these aren’t exclusive to robots and AI. But today, all signs indicate we are approaching an inflection point. Whether it is citywide bans of “robot sex brothels” or nationwide efforts to crack down on “ticket scalp- ing bots,” we are witnessing an explosion of interest in regu- lating robots, human enhancement technologies, and all things in between. And that, in turn, means that typological quandaries once confined to philosophy seminars can no longer be dismissed as academic. Want, for example, to crack down on foreign “influence campaigns” by regulating social media bots? Be careful not to define “bot” too broadly (like the California legislature recently did), or the supercomputer nes- tled in your pocket might just make you one. -

A Long Strange Trip Through the Evolution of Fan Production, Fan

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2017 A Long Strange Trip through the Evolution of Fan Production, Fan-Branding, and Historical Representation in the Grateful Dead Online Archive Anna Richardson Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Communication Studies at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Richardson, Anna, "A Long Strange Trip through the Evolution of Fan Production, Fan-Branding, and Historical Representation in the Grateful Dead Online Archive" (2017). Masters Theses. 2694. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2694 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� 8STER,."l [LLJNOIS UNIVERSITY" Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. -

Find Doc ^ Deadheads: Stories from Fellow Artists, Friends

OX2SOTWE87CB » Kindle » Deadheads: Stories from Fellow Artists, Friends Followers of the Grateful Dead Read PDF DEADHEADS: STORIES FROM FELLOW ARTISTS, FRIENDS FOLLOWERS OF THE GRATEFUL DEAD Audible Studios on Brilliance, 2016. CD-Audio. Condition: New. Unabridged. Language: English . Brand New. Just what was it about the Grateful Dead that made them rock and roll s most beloved band? In Deadheads, those with the real story, who were there and are still listening to the music, explain it all. Grateful Dead lyricist John Perry Barlow talks about his lifelong friendship with Dead guitarist Bob Weir. Cajun chef Rick Begneaud shares his memories of feeding the Dead. John... Download PDF Deadheads: Stories from Fellow Artists, Friends Followers of the Grateful Dead Authored by Dr Linda Kelly Released at 2016 Filesize: 9.12 MB Reviews It in a of my personal favorite pdf. Of course, it really is play, nevertheless an amazing and interesting literature. It is extremely difcult to leave it before concluding, once you begin to read the book. -- Nicholas Ratke I actually started reading this article ebook. I have got read and so i am certain that i will going to study once more yet again in the future. I am just very happy to inform you that this is the finest publication we have read in my personal lifestyle and may be he finest ebook for ever. -- Mrs. Clotilde Hansen II This publication is wonderful. it was actually writtern very completely and benecial. You may like the way the writer compose this publication. -- Prof. Aisha Mosciski PhD TERMS | DMCA. -

A Critique of Barlow's “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace”

A Critique of Barlow’s “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace” by Reilly Jones ©1996 Reilly Jones - All Rights Reserved Published in Extropy #17 - vol. 8, no. 2, 2nd Half 1996 Last February, responding to U.S. passage of the Telecommunications Reform Act, John Perry Barlow, writer, lyricist for the Grateful Dead, and co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, disseminated on-line “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.”1 In this polemic, he declared cyberspace independent of external sovereignty. His assertion generated much discussion, pro and con, leading Barlow to respond publicly in Wired magazine.2 Although a federal court ruled that the Communications Decency Act‟s content-based regulation of the Internet medium violates the U.S. Constitution‟s First Amendment, Barlow‟s broad rejection of State jurisdiction over cyberspace remains in force and, as I will show, subject to criticism. Malignant Political Universalism Barlow‟s “Declaration” contains a dormant intellectual malignancy that could grease the path to universal tyranny. That malignancy lies in expressions of political universalism, a recurring utopian urge that has only produced misery. His use of phrases such as “global social space,” and “Social Contract,” highlight an all too familiar affinity with the sorts of „universal rights‟ that have left a bloody trail from the French Revolution down through the Cold War. Barlow proposes to form a global cyberspace polity, “where anyone, anywhere may express his or her beliefs,” with impunity. He advocates the imposition of the American polity‟s unique right to free speech on all the world‟s polities. The creation of any global polity for the purpose of securing such a universal right, could act as a catalyst to the formation of a World State. -

Inventing the Future: Barlow and Beyond

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duke Law Scholarship Repository INVENTING THE FUTURE: BARLOW AND BEYOND CINDY COHN We are creating a world that all may enter without privilege or prejudice accorded by race, economic power, military force, or station of birth. We are creating a world where anyone, anywhere may express his or her beliefs, no matter how singular, without fear of being coerced into silence or conformity. We will create a civilization of the Mind in Cyberspace. May it be more humane and fair than the world your governments have made before.1 I know the purpose of this volume is not to merely praise or bury John Perry Barlow, but to use him as a jumping off point. But I don’t think I can get to the second part without addressing what many of his critics miss about what he was trying to do with the A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace (Declaration). Since Barlow’s death, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to ensure that the straw men who have Barlow’s face taped to them don’t overshadow the actual man. The basic straw man story goes like this: Barlow was the leader of a band of naïve techno-utopians who believed that the Internet would magically fix all problems without creating any new ones. History has shown that the Internet didn’t solve all problems and created many new ones, so Barlow was a fool or worse. Pieces like this showed up periodically during his lifetime too. -

Property in Cyberspace Harold Smith Reevest

Property in Cyberspace Harold Smith Reevest An effective and efficient system of Internet' regulation requires a workable system of boundary definition and mainte- nance.2 In the physical world, drawing and maintaining bound- aries are frequently the subjects of litigation. It is likely that virtual boundary definition will similarly become a popular subject of litigation, and such definition will be no less legally problematic in the virtual world than it is in the physical world. t A.B. 1991, Princeton University; J.D. Candidate 1996, The University of Chicago. The Internet, Cyberspace, and the Net are terms used throughout this Comment to refer to the collection of roughly 2.2 million computers now connected by interlinked computer networks. 2 Although the courts have had only a handful of opportunities to address the legal issues raised by the use of this new medium, increased interest in the Internet by the leg- islative and executive branches, as well as by law enforcement agencies, suggests that the law will soon be called upon to resolve a variety of disputes on the information super- highway. Cases addressing Internet issues include United States v Morris, 928 F2d 504 (2d Cir 1991) (prosecution of the creator of the "Internet Worm"); Cubby, Inc. v CompuServe Inc., 776 F Supp 135 (S D NY 1991) (holding that a commercial computer bulletin board service is a distributor for purposes of libel); Sega Enterprises Ltd. v Maphia, 857 F Supp 679 (N D Cal 1994) (holding computer bulletin board service liable for copyright and trademark infringement); United States v LaMacchia, 871 F Supp 535 (D Mass 1994) (holding that person who distributed copyrighted software through a computer bulletin board service did not violate the wire fraud statute). -

John Perry Barlow, Cognitive Dissident." on America On-Line, He Describes His Occupation As "Troublemaker"

“COGNITIVE DISSIDENT” John Perry Barlow '69 rides fences on the electronic frontier by Lisa Greim '81 (written for Wesleyan magazine, an alumni publication) To the surprise of many who know him, John Perry Barlow '69 has become respectable. In the last six years, Barlow, 46, has evolved from Wyoming cattle rancher into one of the nation's most outspoken computer experts and defenders of the right to digital freedom. He and Lotus Development Corp. founder Mitchell Kapor started the Electronic Frontier Foundation one snowy afternoon in Barlow's kitchen in Pinedale, Wyoming, a tiny town west of the Wind River Range of the Tetons. "I don't know anyone else who is welcome at the White House, backstage at a Grateful Dead concert, at CIA headquarters, and at a convention of teenage hackers," says Howard Rheingold, author of The Virtual Community. "I listen to him carefully. I don't take everything as gospel, but I do take it all seriously." In all he does, Barlow appears to get a huge charge out of being an anachronism, a Mormon kid turned acidhead turned farmer turned technological philosopher, "probably the only former Republican county chairman in America," he says, "willing to call himself a hippie mystic without lowering his voice." He travels the world, lectures widely, and his writing has appeared in publications as disparate as Mondo 2000 and the New York Times. But his outlaw reputation lingers: When Barlow's friends on The WELL (Whole Earth 'Lectronic Link), an on-line conferencing service, heard that we would meet at a prep school trustees meeting, many assumed he was there to subvert it. -

2005 Annual Report – Expanding Connections in Our Twenty-fi Rst Year, Rex Strengthened Its Presence and Organizations in Those Communities

Furthering a Tradition of Grassroots Giving 2005 Annual Report – Expanding Connections In our twenty-fi rst year, Rex strengthened its presence and organizations in those communities. In partnership with The giving capacity through continued outreach to an increas- Libra Foundation, Rex identifi ed and lent support to California ingly broad base of supporters and collaborators. Musicians organizations promoting environmental justice, conservation and fans came together for a benefi t concert at Berkeley’s and preservation, and sustainable agriculture. Word spread Greek Theater for “Comes a Time,” a celebration of the across the internet about the Rex Community Caravan, creative and humanitarian legacy of Jerry Garcia and and new riders joined our philanthropic journey. This report the Grateful Dead. Black Tie-Dye Balls in New York and describes the 2005 Rex Awards and Grants, events and Washington, DC, initiated new relationships with grassroots fundraising activities, and collaborations. Mercy Corps Mercy Corps Mercy / / / Photo: Henry McInnis / Sunday Mail Photo: Cassandra Nelson Cassandra Photo: Nelson Cassandra Photo: West Sudan, Darfur Refugee Camps RALPH J. GLEASON AWARD BILL GRAHAM AWARD JERRY GARCIA AWARD In memory of music journalist Ralph J. Gleason, a In memory of pioneering producer and founding Rex In memory of Grateful Dead guitarist and founding Rex major fi gure in the advancement of music in America in board member Bill Graham, himself a refugee, this award board member Jerry Garcia, this award is designed to the 1960s, whose openness to new music and ideas tran- is for those working to assist children who are victims honor and support individuals and groups that work scended differences between generations and styles.