Migrações Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study on State Asset Management in the EU

Study on State asset management in the EU Final study report for Pillar 2 – Portugal Contract: ECFIN/187/2016/740792 Written by KPMG and Bocconi University February 2018 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs Directorate Fiscal policy and policy mix and Directorate Investment, growth and structural reforms European Commission B-1049 Brussels 2 Portugal This Country fiche presents a quantitative overview of the mix of non-financial assets owned by the Portuguese General government. A recap and a summary table on sources of data and valuation methods used to map and assess (as far as possible) non-financial assets owned by the Portuguese General government is reported in the Appendix (Table C). 1. OVERVIEW OF NON-FINANCIAL ASSETS In 2015, the estimated value of Non-financial assets owned by the Portuguese General government was equal to 119.6 Eur Bn, accounting for about 82.9% of the estimated value of all assets (including Financial assets) owned by the General government1. Figure 1 General government’s Financial and Non-financial assets (Eur Bn), Portugal, 2015 Source: KPMG elaboration. Data on Gross Domestic Product were directly retrivied from Eurostat on 19th September 2017. (1) Estimated values refer to 2015 as the latest available year for both financial assets and all clusters of non-financial assets. (2) In this chart, the “estimated value” of financial assets is reported in terms of Total Assets of the country’s PSHs as weighted by the stake(s) owned by the Public sector into the PSHs themselves2. (3) Values of Dwellings, and Buildings other than dwellings were directly retrieved from Eurostat, while values for other Non-financial assets were estimated according to the valuation approaches explained in the Methodological Notes for Pillar 2. -

Environmental Performance Report 2020 Environmental Performance Report 2020

ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE REPORT 2020 ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE REPORT 2020 01 07 INTRODUCTION WASTE 02 08 NOISE BIODIVERSITY 03 09 AIR QUALITY ENVIRONMENTAL 04 MANAGEMENT OF VOLUNTARY CARBON CONSTRUCTION WORK MANAGEMENT 10 05 RAISING ENVIRONMENTAL ENERGY AWARENESS 06 11 WATER CONCLUSIONS 2 53 ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE REPORT 2020 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION This document presents the company's main environmental performance results of 2020 and aims to inform ANA's main stakeholders and the general public. ANA – Aeroportos de Portugal, SA (ANA) seeks continuous improvement in its environmental performance and, to this end, the company has an Integrated Management System that takes the Environmental component into account. It defines the priority actions due to the environmental impacts arising from the activity, setting out strategic action goals, which include efficient consumption of energy and water, monitoring and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, controlling potentially pollutant emissions, land use and water resource management, promoting the reduction, reuse and recycling of waste, noise management and biodiversity conservation. 3 53 ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE REPORT 2020 CHART 1 CHANGES IN TRAFFIC UNITS AT ANA AIRPORTS BETWEEN 2019 AND 2020 2020 was a year marked by the 0.0 COVID–19 pandemic and its effects -10.0 on society as a whole, including the -20.0 world aviation sector as a result of the -30.0 substantial reduction in traffic compared -47% -40.0 -2.8% to the previous year (Chart 1). -68.8% -64.4% -75.6% -63.2% -44.1% -61.6% -64,4% -66,7% -50.0 -60.0 -70.0 -80.0 AHD ASC AFR ABJ AJPII ASM AHR AFL AM APS AHD - Humberto Delgado Airport, in Lisbon; ASC - Francisco Sá Carneiro Airport, in Porto ; AFR - Faro Airport; ABJ - Beja Airport; AJPII - João Paulo II Airport, in Ponta Delgada; ASM - Santa Maria Airport; AHR Horta Airport; AFL - Flores Airport; AM - Madeira Airport; APS - Porto Santo Airport; TU – Traffic Unit (1 TU is equivalent to 1 passenger or 100 kg of cargo). -

Charges Guide Airlines.Pdf

Index 1. Airlines 3 1.1 Price List 4 Humberto Delgado Airport Porto Airport Faro Airport Beja Airport Azores Airports Madeira Airports 1.2 Charge Description 15 1.3 Regulatory Framework 19 1.4 Incentives 21 2. Billing and Payment Charges 80 3. Glossary 82 4. Contacts 84 Charges Guide Airlines IMPORTANT: This document is issued for information purposes only, providing a quick reference to the charges applied in airports under ANA´s responsibility. Updated: 6 of March 2019 1. Airlines 1.1 Price List 1.2 Charge Description 1.3 Regulatory Framework 1.4 Incentives Charges Guide Airlines 1.1 Price List Aircraft using the airport are subject to the following charges, exclusive of VAT (Value Added Tax). Humberto Delgado Airport CHARGES 11 Jan – 6 Mar 7 Mar - Dec 1. LANDING/TAKE-OFF Aircrafts up to 25 tonnes, per tonne € 6.34 € 6.45 Aircrafts 25 to 75 tonnes, per tonne above 25 tonnes € 7.54 € 7.68 Aircrafts 75 to 150 tonnes, per tonne above 75 tonnes € 8.86 € 9.02 Aircrafts over 150 tonnes, per tonne above 150 tonnes € 6.73 € 6.85 Minimum charge per landing € 298.36 € 303.73 2. PARKING Traffic Areas (a): Aircrafts up to 14 tonnes (per 24h or fraction) up to 12h or fraction € 28.07 € 28.58 12h to 24h or fraction € 28.07 € 28.58 24h to 48h or fraction € 70.13 € 71.39 48h to 72h or fraction € 115.52 € 117.60 over 72h or fraction € 166.93 € 169.93 Aircrafts over 14 tonnes (per tonne) up to 12h or fraction € 1.89 € 1.92 12h to 24h or fraction € 1.89 € 1.92 24h to 48h or fraction € 4.71 € 4.79 48h to 72h or fraction € 7.76 € 7.90 over 72h or fraction € 11.23 € 11.43 Surcharge (per 15 minutes or fraction) € 70.83 € 72.10 Air Bridge (GPS included) 1 Air bridge, per minute of use, up to 2 hours € 4.16 € 4.23 1 Air bridge, per minute of use, over 2 hours € 4.96 € 5.05 GPS (Ground Power System) per minute of use € 1.43 € 1.46 3. -

Charges Guide Ana Network

CHARGES GUIDE ANA NETWORK INDEX 1. GROUND HANDLING OPERATORS 4 1.1 Price List – Ground Handling Charges 5 Lisbon Airport 5 Porto Airport 8 Faro Airport 10 Beja Airport 12 Azores Airports 14 Madeira Airports 16 2. BILLING AND CHARGES PAYMENTS 19 3. CONTACTS 21 Charges Guide IMPORTANT: This document is issued for information purposes only, providing a quick reference to the charges applied in airports under ANA´s responsibility. Updated: 27th of April 2021 3 1. GROUND HANDLING OPERATORS 1.1 Price list – Ground Handling Charges Charges Guide Ground Handling Operators 1.1 Price List – Ground Handling Charges Aircraft using the airport are subject to the following charges. exclusive of VAT (Value Added Tax). Lisbon Airport CHARGES Apr – Dec 2021 1. PASSENGER HANDLING (per check-in desk) Traditional check-in desk and Self-service Drop off For the first four periods of 15 minutes or fraction € 2.04 For the following 15 minutes or fraction € 1.97 Self-baggage drop off (per baggage) €0.33 Per month € 1,690.09 2. BAGGAGE HANDLING Per embarked baggage processed at the sorting baggage system € 0.41 3. GROUND ADMINISTRATION AND SUPERVISION (by aircraft type) 0 < MTOW aircraft (ton) <15 € 0.09 15 ≤ MTOW aircraft (ton) <30 € 0.42 30 ≤ MTOW aircraft (ton) <55 € 0.75 55 ≤ MTOW aircraft (ton) <72 € 1.20 72 ≤ MTOW aircraft (ton) <82 € 1.33 82 ≤ MTOW aircraft (ton) <170 € 1.62 MTOW aircraft (ton) ≥170 € 2.12 4. FREIGHT AND MAIL HANDLING (by traffic unit) Charge € 0.53 5. RAMP HANDLING (by aircraft type) 0 < MTOW aircraft (ton) <15 € 2.36 15 ≤ MTOW aircraft (ton) <30 € 11.07 30 ≤ MTOW aircraft (ton) <55 € 19.42 55 ≤ MTOW aircraft (ton) <72 € 31.27 72 ≤ MTOW aircraft (ton) <82 € 34.45 82 ≤ MTOW aircraft (ton) <170 € 42.05 MTOW aircraft (ton) ≥170 € 55.31 5 Charges Guide Ground Handling Operators 6. -

Charges Guide - Airlines.Pdf

Index 1. Airlines 3 1.1 Price List 4 Lisbon Airport Porto Airport Faro Airport Beja Airport Azores Airports Madeira Airports 1.2 Charge Description 15 Landing/Take off Aircraft Parking Air Bridges and GPS Passenger Service Airport Opening Time PRM Charge (Passenger Reduced Mobility) Scurity Charge Official Entities (ANAC and Terminal Control) 1.3 Regulatory Framework 19 1.4 Incentives 21 2. Billing and Charges Payment 23 3. Glossary 25 4. Contacts 27 Charges Guide IMPORTANT: This document is issued for information purposes only, providing a quick reference to the charges applied in airports under ANA´s responsibility. Updated: 1st of January 2018 1. Airlines 1.1 Price List 1.2 Charge Description 1.3 Regulatory Framework 1.4 Incentives Charges Guide Airlines Aircraft using the airport are subject to the following charges, exclusive of VAT (Value Added Tax). Lisbon Airport CHARGES 2018 1. LANDING/TAKE-OFF Aircrafts up to 25 tonnes, per tonne Aircrafts 25 to 75 tonnes, per tonne above 25 tonnes Aircrafts 75 to 150 tonnes, per tonne above 75 tonnes Aircrafts over 150 tonnes, per tonne above 150 tonnes Minimum charge per landing 2. PARKING Traffic Areas (a): Aircrafts up to 14 tonnes (per 24h or fraction) up to 12h or fraction 12h to 24h or fraction 24h to 48h or fraction 48h to 72h or fraction over 72h or fraction Aircrafts over 14 tonnes (per tonne) up to 12h or fraction 12h to 24h or fraction 24h to 48h or fraction 48h to 72h or fraction over 72h or fraction Surcharge (per 15 minutes or fraction) Air Bridge (GPS included) 1 Air bridge, per minute of use, up to 2 hours 1 Air bridge, per minute of use, over 2 hours GPS (Ground Power System) per minute of use 5 Charges Guide Airlines 3. -

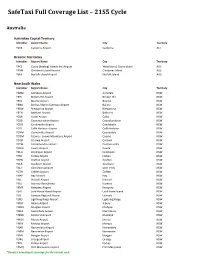

Safetaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Australia Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER -

Environmental Performance Report 2016

ÍNDICE MOD 064605 03 MOD 064605 Page 1 of 20 AATABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Noise and Air Quality ....................................................................................................................... 4 3. Voluntary Carbon Management ...................................................................................................... 6 4. Energy .............................................................................................................................................. 7 5. Water ............................................................................................................................................... 9 6. Waste ............................................................................................................................................. 11 7. Biodiversity .................................................................................................................................... 13 8. Environmental Management of Works ......................................................................................... 16 9. Environmental Awareness ............................................................................................................. 17 10. Conclusions .................................................................................................................................... 19 MOD 064605 03 MOD 064605 -

How Can Portfolio Attract People on Airport Retail Environment?

How can Portfolio attract people on airport retail environment? Joana dos Santos Ramos Tição Supervisor: Paulo Gonçalves Marcos, PhD Dissertation in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of MSc in Business Administration, at the Universidade Católica Portuguesa, January 2015 Abstract Title: How can Portfolio attract people on airport retail environment? Author: Joana dos Santos Ramos Tição Being present on the airport retail environment forces companies to frame their strategies based on this industry particularities. Here there are very distinct characteristics from all the others retail environments such as, consumers’ schedules and culture. Portfolio is the largest retail space inside Lisbon’s international airport restrict zone. With more than 400 m2 this store offers consumers a selection of the best Portuguese products of all kind of industries. The store used to be alone just in front of the Lojas Francas de Portugal’s exit and it was one of the first stores that passengers saw after passing the airport’s security point. On July 2013, with the opening of a new commercial area, international competitors surrounded Portfolio. Besides new consumers passing by, the new commercial area was not giving Portfolio the expected revenues. It was time to define what was the next step to do. Two options were being taken into account, develop a communication strategy, complemented by store improvement or bet in impulse shopping in order to attract more passengers and increase the number of tickets. Key-words: Airport Retail; Lisbon International Airport; Communication Strategy; Impulse Shopping i Resumo Título: Como pode a Portfolio atrair mais consumidores no ambiente de retalho aeroportuário? Autor: Joana dos Santos Ramos Tição Estar presente no ambiente do retalho aeroportuários força as empresas a adaptar a sua estratégia com base nas particularidades desta industria. -

Safetaxi Europe Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Europe Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Albania Identifier Aerodrome Name City Country LATI Tirana International Airport Tirana Albania Armenia Identifier Aerodrome Name City Country UDSG Shirak International Airport Gyumri Armenia UDYE Erebuni Airport Yerevan Armenia UDYZ Zvartnots International Airport Yerevan Armenia Armenia-Georgia Identifier Aerodrome Name City Country UGAM Ambrolauri Airport Ambrolauri Armenia-Georgia UGGT Telavi Airport Telavi Armenia-Georgia UGKO Kopitnari International Airport Kutaisi Armenia-Georgia UGSA Natakhtari Airport Natakhtari Armenia-Georgia UGSB Batumi International Airport Batumi Armenia-Georgia UGTB Tbilisi International Airport Tbilisi Armenia-Georgia Austria Identifier Aerodrome Name City Country LOAV Voslau Airport Voslau Austria LOLW Wels Airport Wels Austria LOWG Graz Airport Graz Austria LOWI Innsbruck Airport Innsbruck Austria LOWK Klagenfurt Airport Klagenfurt Austria LOWL Linz Airport Linz Austria LOWS Salzburg Airport Salzburg Austria LOWW Wien-Schwechat Airport Wien-Schwechat Austria LOWZ Zell Am See Airport Zell Am See Austria LOXT Brumowski Air Base Tulln Austria LOXZ Zeltweg Airport Zeltweg Austria Azerbaijan Identifier Aerodrome Name City Country UBBB Baku - Heydar Aliyev Airport Baku Azerbaijan UBBG Ganja Airport Ganja Azerbaijan UBBL Lenkoran Airport Lenkoran Azerbaijan UBBN Nakhchivan Airport Nakhchivan Azerbaijan UBBQ Gabala Airport Gabala Azerbaijan UBBY Zagatala Airport Zagatala Azerbaijan Belarus Identifier Aerodrome Name City Country UMBB Brest Airport Brest Belarus UMGG -

2020 VINCI Concessions Activity Report

2020 2021 Activity Report T S I I V O E P P O E S I T I V Introduction Discover Positive mobility, E N T S I our vision for today A S E and tomorrow L P. 02 M Y O T Joint interview: B I L I Nicolas Notebaert, Chief Executive Officer of VINCI Concessions and President of VINCI Airports and Jean-François Rial, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Voyageurs du Monde and President of the Paris Tourist Office P. 04 Safeguarding continuity P. 10 Upholding strict safety measures P. 14 Keeping our Positive Mobility promises P. 18 Maintaining performance P. 24 Building new ties P. 30 Analyse Our identity A G Profile G E N P. 60 D E International Presence P. 62 M Key figures Y P. 64 O T Stronger together B I P. 66 I L Governance P. 68 Acting as a socially responsible company P. 36 Working towards sustainable mobility P. 40 Innovating together P. 50 02 — 03 Harnessing future mobility to provide solutions to the challenges we face in terms of health, the economy and the climate Nicolas Notebaert, Chief Executive Officer of VINCI Concessions, President of VINCI Airports POSITIVE MOBILITY POSITIVE A crisis is always an eye-opening experience, a moment of truth that unlocks the power and energy within us and often accelerates change. We certainly won’t forget 2020 in a hurry. The pandemic hit us hard and tested the resilience of our model, but we pulled through. VINCI Concessions’ employees all over the world worked passionately, skilfully and responsibly to find solutions and support one another. -

Brochura Nova 25.01.21

A MEMBER OF AUREUM GROUP “HOTEL ROYAL SÃO PAULO, THE BEAUTY OF ALENTEJO IN A VILLAGE OF KINGS” ALENTEJO, PORTUGAL The plains that extend as far as the eye can see EUROPE PORTUGAL YOUR GATEWAY TO EU CITIZENSHIP EUROPEAN UNION 2020 NUMBERS EUROPEAN SCHENGEN COUNTRIES AREA EUROZONE PART OF THE EU COUNTRIES COUNTRIES GDP 27 REPRESENT MEMBER 27 26 19 22% GLOBAL STATES GDP Austria Austria Austria Belgium Belgium Belgium Bulgaria Czech Republic Cyprus CRoatia Denmark Estonia SCHENGEN AREA CypRus Estonia Finland ZONE 4.42 MILLION Czech Republic Finland France FREELY KM² Denmark France Germany Estonia Germany Greece Finland Greece Ireland FRance Hungary Italy Germany Iceland Latvia 24 POPULATION GReece Italy Lithuania OFFICIAL +513 MILLION HungaRy Latvia Luxembourg LANGUAGES EST. 2018 IReland Liechtenstein Malta Italy Lithuania the Netherlands Latvia Luxembourg Portugal Lithuania Malta Slovakia Luxembourg Netherlands Slovenia Malta Norway Spain 62 EURO Netherlands YEARS ZONE Poland IN PEACE 19 Poland Portugal COUNTRIES PoRtugal Slovakia Romania Slovenia Slovakia Spain Slovenia Sweden Spain Switzerland Sweden BEING A EUROPEAN CITIZEN MEANS YOU BENEFIT FROM ALL THE BEST THINGS A continent at peace The world`s biggest economy The freedom to move 7 EU CITIZENSHIP RIGHTS FREE POWERFUL FREE NON MEDICAL PASSPORT EDUCATION DISCRIMINATION COVERAGE VISA-WAIVER MOST OF TO 150+ THE COUNTRIES COUNTRIES FREE SAFETY VOTING MOVMENT FOOD & BEING LIVE, WORK STANDARD A CANDIDATE AND STUDY RIGHTS ACROSS EU EUROPE IS A WORLD LEADER IN QUALITY OF LIFE 2020 AVAILABLE -

Environmental Performance Report 2018 Ana Aeroportos De Portugal

ANA AEROPORTOS DE PORTUGAL ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE REPORT 2018 ANA AEROPORTOS DE PORTUGAL 2 ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE REPORT 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS NOISE AND VOLUNTARY CARBON INTRODUCTION AIR QUALITY MANAGEMENT 1PAGE 04 2PAGE 05 3PAGE 8 energY WATER WASTE 4PAGE 11 5PAGE 15 6PAGE 17 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT ENVIRONMENTAL biodiversiTY OF WORKS AWARENESS 7PAGE 19 8PAGE 22 9PAGE 23 conclusIONS PAGE 26 10 3 ANA AEROPORTOS DE PORTUGAL introduCTION ANA – Aeroportos de Portugal, SA (ANA) seeks to ensure the preservation of the environment in its daily management aiming to improve its performance and, insofar as it can, to contribute to building a more sustainable future. To that effect, this document presents ANA’s environmental management in 2018, constituting an ideal means of disclosure, available to ANA’s main stakeholders and to the general public. 4 ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE REPORT 2018 NOISE AND AIR QUALITY Airport activity has been increasingly including environmental and sustainability issues in its agenda, in which “Noise” takes on a special focus. Given the enormous relevance to ANA of issues associated with noise, these are reflected in the Company’s Environmental Policy as a strategic area of priority action. 5 ANA AEROPORTOS DE PORTUGAL Strategies to minimise the impact associated with this environmental descriptor on the airport infrastructure may take on different forms, corresponding to different solutions. The opportunities for noise reduction are at the sources, at the receiving sites and in the routes of propagation. To that effect, a Noise Monitoring System is The optimal solution generally presents itself implemented at the Airports (in continuous as a combination of as many alternatives operation) where this environmental as possible, in order to effectively minimise descriptor is most relevant, seeking to the effects of noise on the neighbouring monitor and control the noise levels, with a community.