The Evolution of Paternity and Paternal Care in Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Life History of the South Temperate Cape Penduline Tit (Anthoscopus Minutus) and North Temperate Remizidae Species

J Ornithol DOI 10.1007/s10336-016-1417-4 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Comparative life history of the south temperate Cape Penduline Tit (Anthoscopus minutus) and north temperate Remizidae species 1,2 1 1 Penn Lloyd • Bernhard D. Frauenknecht • Morne´ A. du Plessis • Thomas E. Martin3 Received: 19 June 2016 / Revised: 22 October 2016 / Accepted: 14 November 2016 Ó Dt. Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V. 2016 Abstract We studied the breeding biology of the south parental nestling care. Consequently, in comparison to the temperate Cape Penduline Tit (Anthoscopus minutus)in other two species, the Cape Penduline Tit exhibits greater order to compare its life history traits with those of related nest attentiveness during incubation, a similar per-nestling north temperate members of the family Remizidae, namely feeding rate and greater post-fledging survival. Its rela- the Eurasian Penduline Tit (Remiz pendulinus) and the tively large clutch size, high parental investment and Verdin (Auriparus flaviceps). We used this comparison to associated high adult mortality in a less seasonal environ- test key predictions of three hypotheses thought to explain ment are consistent with key predictions of the adult latitudinal variation in life histories among bird species— mortality hypothesis but not with key predictions of the the seasonality and food limitation hypothesis, nest pre- seasonality and food limitation hypothesis in explaining dation hypothesis and adult mortality hypothesis. Contrary life history variation among Remizidae species. These to the general pattern of smaller clutch size and lower adult results add to a growing body of evidence of the impor- mortality among south-temperate birds living in less sea- tance of age-specific mortality in shaping life history sonal environments, the Cape Penduline Tit has a clutch evolution. -

Birding Tour to Ghana Specializing on Upper Guinea Forest 12–26 January 2018

Birding Tour to Ghana Specializing on Upper Guinea Forest 12–26 January 2018 Chocolate-backed Kingfisher, Ankasa Resource Reserve (Dan Casey photo) Participants: Jim Brown (Missoula, MT) Dan Casey (Billings and Somers, MT) Steve Feiner (Portland, OR) Bob & Carolyn Jones (Billings, MT) Diane Kook (Bend, OR) Judy Meredith (Bend, OR) Leaders: Paul Mensah, Jackson Owusu, & Jeff Marks Prepared by Jeff Marks Executive Director, Montana Bird Advocacy Birding Ghana, Montana Bird Advocacy, January 2018, Page 1 Tour Summary Our trip spanned latitudes from about 5° to 9.5°N and longitudes from about 3°W to the prime meridian. Weather was characterized by high cloud cover and haze, in part from Harmattan winds that blow from the northeast and carry particulates from the Sahara Desert. Temperatures were relatively pleasant as a result, and precipitation was almost nonexistent. Everyone stayed healthy, the AC on the bus functioned perfectly, the tropical fruits (i.e., bananas, mangos, papayas, and pineapples) that Paul and Jackson obtained from roadside sellers were exquisite and perfectly ripe, the meals and lodgings were passable, and the jokes from Jeff tolerable, for the most part. We detected 380 species of birds, including some that were heard but not seen. We did especially well with kingfishers, bee-eaters, greenbuls, and sunbirds. We observed 28 species of diurnal raptors, which is not a large number for this part of the world, but everyone was happy with the wonderful looks we obtained of species such as African Harrier-Hawk, African Cuckoo-Hawk, Hooded Vulture, White-headed Vulture, Bat Hawk (pair at nest!), Long-tailed Hawk, Red-chested Goshawk, Grasshopper Buzzard, African Hobby, and Lanner Falcon. -

GHANA MEGA Rockfowl & Upper Guinea Specials Th St 29 November to 21 December 2011 (23 Days)

GHANA MEGA Rockfowl & Upper Guinea Specials th st 29 November to 21 December 2011 (23 days) White-necked Rockfowl by Adam Riley Trip Report compiled by Tour Leader David Hoddinott RBT Ghana Mega Trip Report December 2011 2 Trip Summary Our record breaking trip total of 505 species in 23 days reflects the immense birding potential of this fabulous African nation. Whilst the focus of the tour was certainly the rich assemblage of Upper Guinea specialties, we did not neglect the interesting diversity of mammals. Participants were treated to an astonishing 9 Upper Guinea endemics and an array of near-endemics and rare, elusive, localized and stunning species. These included the secretive and rarely seen White-breasted Guineafowl, Ahanta Francolin, Hartlaub’s Duck, Black Stork, mantling Black Heron, Dwarf Bittern, Bat Hawk, Beaudouin’s Snake Eagle, Congo Serpent Eagle, the scarce Long-tailed Hawk, splendid Fox Kestrel, African Finfoot, Nkulengu Rail, African Crake, Forbes’s Plover, a vagrant American Golden Plover, the mesmerising Egyptian Plover, vagrant Buff-breasted Sandpiper, Four-banded Sandgrouse, Black-collared Lovebird, Great Blue Turaco, Black-throated Coucal, accipiter like Thick- billed and splendid Yellow-throated Cuckoos, Olive and Dusky Long-tailed Cuckoos (amongst 16 cuckoo species!), Fraser’s and Akun Eagle-Owls, Rufous Fishing Owl, Red-chested Owlet, Black- shouldered, Plain and Standard-winged Nightjars, Black Spinetail, Bates’s Swift, Narina Trogon, Blue-bellied Roller, Chocolate-backed and White-bellied Kingfishers, Blue-moustached, -

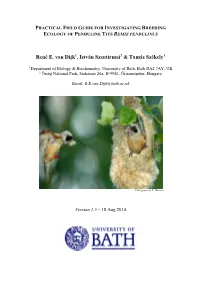

Penduline Tit Field Guide

PRACTICAL FIELD GUIDE FOR INVESTIGATING BREEDING ECOLOGY OF PENDULINE TITS REMIZ PENDULINUS René E. van Dijk1, István Szentirmai2 & Tamás Székely1 1 Department of Biology & Biochemistry, University of Bath, Bath BA2 7AY, UK 2 Őrsèg National Park, Siskaszer 26a, H-9941, Őriszentpéter, Hungary Email: [email protected] Photograph by C. Daroczi Version 1.5 – 18 Aug 2014 Rationale Why study penduline tits? The main reason behind studying penduline tits is their extremely variable and among birds unusual breeding system: both sexes are sequentially polygamous. Both males and females may desert the clutch during the egg-laying phase, so that parental care is carried out by one parent only and, most remarkably, some 30-40% of clutches is deserted by both parents. In this field guide we outline several methods that help us to reveal various aspects of the penduline tit’s breeding system, including mate choice, mating behaviour, and parental care. The motivation in writing this field guide is to guide you through a number of basic field methods and point your attention to some potential pitfalls. The penduline tit is a fairly easy species to study, but at the heart of unravelling its breeding ecology are appropriate, standardised and accurate field methods. Further reading Cramp, S., Perrins, C. M. & Brooks, D. M. 1993. Handbook of the birds of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa – The Birds of the Western Palearctic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Franz, D. 1991. Paarungsystem and Fortpflanzungstrategie der Beutelmeise Remiz pendulinus. Journal für Ornithologie, 132, 241-266. Glutz von Blotzheim, U.N. -

Breeding Systems in Penduline Tits: Sexual Selection, Sexual Conflict and Parental Cooperation

Breeding systems in penduline tits: Sexual selection, sexual conflict and parental cooperation PhD thesis Ákos Pogány Department of Ethology, Biological Institute, Faculty of Science, Eötvös University, Hungary Supervisors Prof. Tamás Székely (Department of Biology and Biochemistry, University of Bath, UK) Dr. Vilmos Altbäcker (Department of Ethology, Eötvös University, Budapest, Hungary) PhD School in Biology Head of PhD School: Prof. Anna Erdei PhD Program in Ethology Head of PhD Program: Dr. Ádám Miklósi − Budapest, 2009 − 1 Table of contents I Introduction .................................................................................................................4 1. Sexual conflict and sexually antagonistic coevolution.................................................4 a) Sexual conflict: development of theory..................................................................4 b) Sexually antagonistic selection and the forms of sexual conflict...........................5 2. Sexual selection............................................................................................................8 a) Evolution of female preference ..............................................................................9 b) Male-female coevolution by sexual selection and sexual conflict.........................9 3. Parental cooperation versus sexual conflict................................................................10 II Study species, objectives and methods.....................................................................12 1. Ecology -

Madrid Hot Birding, Closer Than Expected

Birding 04-06 Spain2 2/9/06 1:50 PM Page 38 BIRDING IN THE OLD WORLD Madrid Hot Birding, Closer Than Expected adrid is Spain’s capital, and it is also a capital place to find birds. Spanish and British birders certainly know M this, but relatively few American birders travel to Spain Howard Youth for birds. Fewer still linger in Madrid to sample its avian delights. Yet 4514 Gretna Street 1 at only seven hours’ direct flight from Newark or 8 ⁄2 from Miami, Bethesda, Maryland 20814 [email protected] Madrid is not that far off. Friendly people, great food, interesting mu- seums, easy city transit, and great roads make central Spain a great va- cation destination. For a birder, it can border on paradise. Spain holds Europe’s largest populations of many species, including Spanish Imperial Eagle (Aquila heliaca), Great (Otis tarda) and Little (Tetrax tetrax) Bustards, Eurasian Black Vulture (Aegypius monachus), Purple Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio), and Black Wheatear (Oenanthe leucura). All of these can be seen within Madrid Province, the fo- cus of this article, all within an hour’s drive of downtown. The area holds birding interest year-round. Many of northern Europe’s birds winter in Spain, including Common Cranes (which pass through Madrid in migration), an increasing number of over-wintering European White Storks (Ciconia ciconia), and a wide variety of wa- terfowl. Spring comes early: Barn Swallows appear by February, and many Africa-wintering water birds arrive en masse in March. Other migrants, such as European Bee-eater (Merops apiaster), Common Nightingale (Luscinia megarhynchos), and Golden Oriole (Oriolus ori- olous), however, rarely arrive before April. -

Namibia & Botswana

Namibia & Botswana Custom tour 31st July – 16th August, 2010 Tour leaders: Josh Engel & Charley Hesse Report by Charley Hesse. Photos by Josh Engel & Charley Hesse. This trip produced highlights too numerous to list. We saw virtually all of the specialties we sought, including escarpment specialties like Rockrunner, White-tailed Shrike, Hartlaub‟s Francolin, Herero Chat and Violet Wood-hoopoe and desert specialties like Dune and Gray‟s Larks and Rueppell‟s Korhaan. We cleaned up on Kalahari specialties, and added bonuses like Bare-cheeked and Black-faced Babblers, while also virtually cleaning up on swamp specialties, like Pel‟s Fishing-Owl and Rufous-bellied Heron and Slaty Egret. Of course, with over 40 species seen, mammals provided many memorable experiences as well, including a lioness catching a warthog at one of Etosha‟s waterholes, only to have it stolen away by a male. Elsewhere, we saw a herd of Hartmann‟s Mountain Zebras in the rocky highlands Bat-eared Foxes in the flat Namib desert on the way to the coast; otters feeding in front of our lodge in Botswana; a herd of Sable Antelope racing in front of the car in Mahango Game Reserve. This trip is also among the best for non- animal highlights, and we stayed at varied and wonderful lodges, eating delicious local food and meeting many interesting people along the way. Tropical Birding www.tropicalbirding.com 1 The rarely seen arboreal Acacia Rat (Thallomys) gnaws on the bark of Acacia trees (Charley Hesse). 31st July After meeting our group at the airport, we drove into Nambia‟s capital, Windhoek, seeing several interesting birds and mammals along the way. -

Levels of Extra-Pair Paternity Are Associated with Parental Care in Penduline Tits (Remizidae)

This is a repository copy of Levels of extra-pair paternity are associated with parental care in penduline tits (Remizidae). White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/109970/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Ball, A.D., van Dijk, R.E., Lloyd, P. et al. (6 more authors) (2017) Levels of extra-pair paternity are associated with parental care in penduline tits (Remizidae). Ibis, 159 (2). pp. 449-455. ISSN 1474-919X https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12446 This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Ball, A. D. et al (2016), Levels of extra-pair paternity are associated with parental care in penduline tits (Remizidae). Ibis, which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12446. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

University of Groningen Polymorphic Microsatellite DNA Markers

University of Groningen Polymorphic microsatellite DNA markers in the penduline tit, Remiz pendulinus Meszaros, L. A.; Frauenfelder, N.; Van Der Velde, M.; Komdeur, J.; Szabad, J. Published in: Molecular Ecology Resources DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.02050.x IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2008 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Meszaros, L. A., Frauenfelder, N., Van Der Velde, M., Komdeur, J., & Szabad, J. (2008). Polymorphic microsatellite DNA markers in the penduline tit, Remiz pendulinus. Molecular Ecology Resources, 8(3), 692-694. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.02050.x Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 16-01-2020 Molecular Ecology Resources (2008) 8, 692–694 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.02050.x PERMANENTBlackwell Publishing Ltd GENETIC RESOURCES Polymorphic microsatellite DNA markers in the penduline tit, Remiz pendulinus L. -

Cape Penduline

120 Remizidae: penduline tits Escarpment and Kalahari. In the Fynbos it is confined to lowland renosterveld and coastal strandveld (Hockey et al. 1989); it is not found in mountain fynbos. In the eastern Cape Province it remains mostly within Acacia karroo thickets (Skead 1959). In the drier parts of the range it has an affinity for thickets along watercourses (Maclean 1993b). Movement: Reporting rates are widely scattered and no consistent evidence for seasonal movements is discernible. It appears to be resident throughout its range, but presum- ably it wanders in response to localized rainfall events. Breeding: In the winter-rainfall region of the south- western Cape Province, egglaying has been recorded July– November (Winterbottom 1968a), but October–January in the Transvaal, September–January in Botswana, and September–March (January peak) in Namibia (Tarboton et al. 1987b; Skinner 1995a; Brown & Clinning in press). These data suggest breeding in response to rainfall. The atlas data conform to this pattern. Interspecific relationships: The ranges of the Cape and Grey Penduline Tits overlap. However, the Cape Penduline Tit normally prefers open thornveld whereas, in the area of contact, the Grey Penduline Tit prefers broadleaved woodland such as Brachystegia, Baikiaea and Mopane. They are therefore mostly parapatric (cf. Brewster 1991) but have occasionally been recorded in mixed flocks dur- ing winter (Ginn et al. 1989). Historical distribution and conservation: Atlas data extend its known range in the central and northern Trans- vaal (cf. Maclean 1993b). The Cape Penduline Tit is wide- spread and common and responds positively to thornbush Cape Penduline Tit encroachment resulting from overgrazing in arid areas. -

Season Dispersal in Penduline Tits?

Ornis Hungarica (2009) 17-18: 33-45. Do mating opportunities influence within- season dispersal in Penduline Tits? ORSOLYA KISS AND ISTVÁN SZENTIRMAI Kiss, O. and Szentirmai, I. 2009. Do mating opportunities influence within-season dispersal in Penduline Tits? – Ornis Hung. 17-18: 33-45. Abstract To find better mating opportunities may be one of the reasons why birds disperse from one population to another, although evidence is scarce to prove this proposition. Penduline Tit is a highly suitable model species to clarify this question, since both males and females may have several mates during a single breeding season. We followed the dispersal of Penduline Tits in a system consisting of six popula- tions. Our study provided evidence for short distance within-season breeding dispersal in Penduline Tit between our study sites. Both the rate of immigration and emigration showed a strong seasonal pattern, which may be related to the fluctuation in mating opportunities. The number of immigrating males increases with the number of unmated females in the population, i.e. mating opportunities of males. Furthermore, the number of unmated males (mating opportunities of females) in the population increased with the number of immigrating males. Our results thus indicate a relationship between dispersal behaviour and mating opportunities in Penduline Tits. Further stud- ies are needed to distinguish between cause and effect. Keywords: dispersal, Remiz pendulinus, mating system, mating opportunities Összefoglalás A szaporodási időszakon belüli diszperzió egyik lehetséges oka, hogy az egyedek az optimális szaporodási feltételek érdekében vándorolnak át az egyik populációból a másikba, bár kevés bizonyíték támasztja alá ezt a feltételezést. -

Rwanda Trip Report

Rwanda Trip Report 22 nd to 28 th June 2007 Trip report compiled by Keith Valentine Tour Highlights Our action packed one week tour to this fabulous landlocked country produced numerous highlights from the magnificent Mountain Gorillas in the splendid Volcanoes National Park to chasing down the various Albertine Rift Endemics in the seemingly endless montane forests of Nyungwe. Our adventure began in the capital Kigali where we spent the morning visiting the Genocide Memorial, a sobering reminder of this tiny country’s horrific past. The memorial has been excellently set out and provides the visitor with outstanding information and facts regarding not only Rwanda’s genocide but also a history of the many other mass atrocities that have taken place around the world. Our first destination was the vast lakes and savannas of Akagera National Park. Our progress to Akagera was quickly put on hold however as a roadside stop produced a stunning pair of scarce White- collared Oliveback. Other goodies included Bronze Sunbird, Western Citril, Yellow-throated Greenbul, Black-lored Babbler, Black-crowned Waxbill and Thick-billed Seed-eater. Akagera is home to a wide variety of game and birds and provided an excellent introduction to the many widespread species found in Rwanda. Cruising around the network of roads provided excellent views of a number of specials that included Madagascar Pond-Heron, African and Black Goshawk, splendid Ross’ Turaco, Spot-flanked RBT Rwanda Trip Report 2007 Barbet, Tabora Cisticola, Buff-bellied and Pale Wren-Warbler, Greencap Eremomela, Red-faced Crombec, White-winged Black-Tit and African Penduline-Tit, while a short night excursion produced the impressive Verreaux’s Eagle-Owl and Freckled Nightjar.