This Article Discusses the Gothic and Science Fiction Influences Apparent in the Character of Batman, Specifically with Refere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gotham Knights

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 11-1-2013 House of Cards Matthew R. Lieber University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Lieber, Matthew R., "House of Cards" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 367. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/367 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. House of Cards ____________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver ____________________________ In Partial Requirement of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ By Matthew R. Lieber November 2013 Advisor: Sheila Schroeder ©Copyright by Matthew R. Lieber 2013 All Rights Reserved Author: Matthew R. Lieber Title: House of Cards Advisor: Sheila Schroeder Degree Date: November 2013 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to approach adapting a comic book into a film in a unique way. With so many comic-to-film adaptations following the trends of action movies, my goal was to adapt the popular comic book, Batman, into a screenplay that is not an action film. The screenplay, House of Cards, follows the original character of Miranda Greene as she attempts to understand insanity in Gotham’s most famous criminal, the Joker. The research for this project includes a detailed look at the comic book’s publication history, as well as previous film adaptations of Batman, and Batman in other relevant media. -

STARS Half-Virgin

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2011 Half-virgin Alexander Gregory Pollack University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Pollack, Alexander Gregory, "Half-virgin" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1951. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1951 HALF-VIRGIN by ALEXANDER GREGORY POLLACK B.A. Emory University, 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Creative Writing in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2011 © 2011 Alexander Gregory Pollack ii ABSTRACT POLLACK, ALEX. Half-Virgin. (Under the direction of Jocelyn Bartkevicius) Half-Virgin is a cross-genre collection of essays, short stories, and poems about the humor, pain, and occasional glory of journeying into adulthood but not quite getting there. The works in this collection seek to create a definition of a term, “half-virgin,” that I coined in the process of writing this thesis. Among the possibilities explored are: an individual who embarks upon sexual activity for the first time and does not achieve orgasm; an individual who has reached orgasm through consensual sexual activity, but has remained uncertain about what he or she is doing; and the curious sensation of being half-child, half-adult. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Collision Course

FINAL-1 Sat, Jul 7, 2018 6:10:55 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of July 14 - 20, 2018 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH Collision $ 00 OFF 3ANY course CAR WASH! EXPIRES 7/31/18 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnett's Car Wash H1artnett x 5` Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 Ian Anthony Dale stars in 15 WATER STREET “Salvation” DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3 With 35 years experience on the North Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful While Grace (Jennifer Finnigan, “Tyrant”) and Harris (Ian Anthony Dale, “Hawaii Five- The LawOffice of 0”) work to maintain civility in the hangar, Liam (Charlie Row, “Red Band Society”) and STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Darius (Santiago Cabrera, “Big Little Lies”) continue to fight both RE/SYST and the im- Auto • Homeowners pending galactic threat. Loyalties will be challenged as humanity sits on the brink of Business • Life Insurance 978.739.4898 Earth’s potential extinction. Learn if order can continue to suppress chaos when a new Harthorne Office Park •Suite 106 www.ForlizziLaw.com 978-777-6344 491 Maple Street, Danvers, MA 01923 [email protected] episode of “Salvation” airs Monday, July 16, on CBS. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Northridge Review

Northridge Review Spring 2013 Acknowledgements The Northridge Review gratefully acknowledges the Associated Students of CSUN and the English Department faculty and staff,Frank De La Santo, Marjie Seagoe, Tonie Mangum, and Marleene Cooksey for all their help. Submission Information The N orthridge Review accepts submissions of fiction, creative nonfiction, poetry, drama, and art throughout the year. The Northridge Review has recently changed the submission process. Manuscripts can be uploaded to the following page: http://thenorthridgereview.submittable.com/submit Submissions should be accompanied by a cover page that includes the writer's name, address, email, and phone number, as well as the titles of the works submitted. The writer's name should not appear on the manu script itself. Printed manuscripts and all other correspondence can still be delivered to the following address: Northridge Review Department of English California State University Northridge 18111 NordhoffSt. Northridge, CA 91330-8248 Staff Chief Editor Faculty Advisor Karlee Johnson Mona Houghton Poetry Editors Fiction Editor ltiola "Stephanie"Jones Olvard Smith Nicole Socala Fiction Board Poetry Board Aliou Amravanti Kashka Mandela Anna Austin Brown-Burke Jasmine Adame Alexandra Johnson KyleLifton Karlee Johnson Marcus Landon Saman Kangarloo Khiem N gu.yen Kristina Kolesnyk Evon Magana Business Manager Rich McGinis Meaghan Gallagher Candice Montgomery Emily Robles Business Board Alexandra Johnson Layout and Design Editor Karlee Johnson A[iou Amravanti Kashka Mandela ltiola "Stephanie" Jones Brown-Burke Saman Kangarloo Layout and Design Board Desktop Publishing Editors Jasmine Adame Marcus Landon Anna Austin Emily Robles Kyle Lifton Evon Magana Desktop Publishing Board Khiem Nguyen KristinaKolesrryk O[vard Smith Rich McGinis Nicole Socala Candice Montgomery Awards The Northridge Review Fiction Award, given annually, recognizes excel lent fiction by a CSUN student published in the Northridge Review. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

When I Open My Eyes, I'm Floating in the Air in an Inky, Black Void. the Air Feels Cold to the Touch, My Body Shivering As I Instinctively Hugged Myself

When I open my eyes, I'm floating in the air in an inky, black void. The air feels cold to the touch, my body shivering as I instinctively hugged myself. My first thought was that this was an awfully vivid nightmare and that someone must have left the AC on overnight. I was more than a little alarmed when I wasn't quite waking up, and that pinching myself had about the same amount of pain as it would if I did it normally. A single star twinkled into existence in the empty void, far and away from reach. Then another. And another. Soon, the emptiness was full of shining stars, and I found myself staring in wonder. I had momentarily forgotten about the biting cold at this breath-taking sight before a wooden door slammed itself into my face, making me fall over and land on a tile ground. I'm pretty sure that wasn't there before. Also, OW. Standing up and not having much better to do, I opened the door. Inside was a room with several televisions stacked on top of each other, with a short figure wrapped in a blanket playing on an old NES while seven different games played out on the screen. They turned around and looked at me, blinking twice with a piece of pocky in their mouth. I stared at her. She stared back at me. Then she picked up a controller laying on the floor and offered it to me. "Want to play?" "So you've been here all alone?" I asked, staring at her in confusion, holding the controller as I sat nearby. -

Breaking Kayfabe & Other Stories by Andy Geels a Thesis Submitted To

Breaking Kayfabe & Other Stories by Andy Geels A thesis submitted to the faculty of Radford University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English Thesis Advisor: Dr. Tim Poland April 2018 Copyright 2018, Andy Geels 2 Acknowledgements Thank you, Mom, for transcribing my very first stories, and Dad, for placing an eight- year-old on stage at a Sioux City karaoke bar to sing “Folsom Prison Blues.” You’ve raised an aspiring journalist, knife salesman, professional wrestler, high school algebra teacher, musician, college professor, and, now, a writer. I am blessed beyond belief that you’ve done so. Thank you, Dr. Amanda Kellogg and Dr. Rick Van Noy, for serving on my thesis committee, for your critical input and expertise, and for your support throughout my time at Radford University. Thank you also, Stephan and Jackson, for acting as my readers, for suffering through endless do you think this works, and for taking time out of your own busy lives to give heartfelt and honest feedback at critical moments. Your own creative pursuits inspire me endlessly. Thank you, Emma, not only for reading all these stories a dozen times, but for talking me off the ledge of my own self-doubt, for affirming me in my moments of existential dread, and for motivating me to create something I can be proud of. I am incalculably lucky, my dearest partner of greatness. Finally, the completion of this collection would not have been possible without the patience and dedication of Dr. Tim Poland, whose guidance and mentorship were paramount to the project, as well as to my own personal growth as a writer, scholar, and man. -

The Dark Knight Rises, Batman Has Once Again Saved Gotham City from Ruin, but at The—Ostensible—Cost of His Own Life

A Deep, Deep Sleep Confronting America’s destructive Ambivalence toward home-Grown Violence By Tom Kutsch t the end of the film The Dark Knight Rises, Batman has once again saved Gotham City from ruin, but at the—ostensible—cost of his own life. “I see A a beautiful city,” Police Commissioner Jim Gordon notes somberly at the funeral of Bruce Wayne, the superhero’s alter ego. “A brilliant people… rising from this abyss. I see the lives for which I lay down my life… It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.” The eloquence is not Gordon’s own of course, but rather that of Charles Dickens. In A Tale of Two Cities, the lines are spoken by the character Sydney Carton—like Wayne, an orphan intent on saving his city from destruction—on the eve of his own execution. It’s a hopeful denouement to Christopher Nolan’s reboot of the Batman franchise, which started in 2005 with Batman Begins, continued with The Dark Knight in 2008, and concluded this summer with The Dark Knight Rises. Yet, Gordon’s eulogy comes tinged with weariness toward violence and the heavy price Gotham has levied to stave off its own destruction. Nolan’s trilogy injects realism into the superhero narrative; a sense that, even though the rock ‘em, sock ‘em action is quite over the top, many of the film’s sce- narios seem plausible. Indeed, The Dark Knight Rises is a parable that explores the fear and anxiety abroad in the land, and in turn explores fundamental social questions confronting Americans. -

Low a Loner’S Kit to Become Their Most Special Rank

PARTNERS Twist Fate This book was made possible through a partnership between the Connected Learning Alliance, Wattpad, DeviantArt, the National Writing Project, and the Young Adult Library Services Association. About the Partners Connected Learning Alliance The Connected Learning Alliance supports the expansion and influence of a network of educators, experts, and youth-serving organizations, mobilizing new technology in the service of equity, access, and opportunity for all young people. The Alliance is coordinated by the Digital Media and Learning Research Hub at UC Irvine. Learn more at clalliance.org. Wattpad Wattpad, the global multiplatform entertainment company for original stories, transforms how the world discovers, creates, and engages with stories. Since 2006, it has offered a completely social experience in which people everywhere can participate and collaborate on content through comments, messages, and multimedia. Today, Wattpad connects a community of more than 45 million people around the world through serialized stories about the things they love. As home to millions of fresh voices and fans who share culturally relevant stories based on local trends and current events, Wattpad has unique pop culture insights in virtually every market around the world. Wattpad Studios coproduces stories for film, television, digital, and print to radically transform the way the entertainment industry sources and produces content. Wattpad Brand Solutions offers new and integrated ways for brands to build deep engagement with consumers. The company is proudly based in Toronto, Canada. Learn more at wattpad.com/about. PARTNERS DeviantArt Founded in 2000, DeviantArt is an online social network for artists and art enthusiasts and a platform for emerging and established artists to exhibit, promote, and share their works with an enthusiastic, art-centric community. -

DOG MEASURE 070513Web

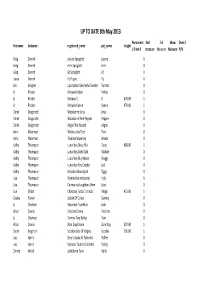

UP TO DATE 8th May 2013 Permanent 2nd 3rd Show Over 2 firstname lastname registered_name pet_name height 1 if not 0 measure Measure Measure Y/N Greg Derrett Jaycee Sproglett Jaycee 0 Greg Derrett Fern Sproglett Fern 0 Greg Derrett Gt Sproglett Gt 0 Laura Derrett FlyPuppy Fly 0 Jim Gregson Lipsmackin Gesviesha Twister Twister 0 Jo Rhodes Moravia Kelbie Kelbie 0 Jo Rhodes Moravia Ci Ci 470.00 1 Jo Rhodes Moravia Kaesie Kaesie 470.00 1 Derek Dragonetti Woodsorrel Jinja Jinja 0 Derek Dragonetti Woodsorrel Red Pepper Pepper 0 Derek Dragonetti Aligan The Wizard Aligan 0 Anne Alderman Wotta Lotta Tosh Tosh 0 Anne Alderman Trueline Waveney Breeze 0 Kathy Thompson Lunarlites Dizzy Mix Dizzy 488.00 1 Kathy Thompson Lunarlites Dark Gold Maddie 0 Kathy Thompson Lunarlites Blue Moon Braggi 0 Kathy Thompson Lunarlites Fire Cracker Jed 0 Kathy Thompson Myndoc Moon Spirit Tiggy 0 Lisa Thompson Wynmallen Indiscreet Indy 0 Lisa Thompson Caninarosa Laughters Here Jake 0 Sue Elliott Chakotay Turbo Tornado Megan 475.00 1 Cayley Turner Splash Of Colour Sammy 0 Jo Chalmers Raeannes True Blue Josh 0 Alison Cronin Fletcher Cronin Fletcher 0 Jo Chalmers Tommy Two Bellies Tom 0 Alison Cronin Zoro Dog Cronin Zoro Dog 507.00 1 Sarah Beighton Scoobie Doo Of Valgray Scoobie 506.00 1 Lois Harris Zero's Aysha At Tolnedra Toffee 0 Lois Harris Starazaz Todd At Tolnedra Toddy 0 Denise Welsh Jadedoren Paris Harlie 0 Cathy Brown Blue Dippy Do Lally Dippy 0 Cathy Brown Dippity Doodah Scooby 0 Soraya Porter Hartsfern In Earnest Ernest 336.00 1 Maureen Goodchild Crystalgorse