Lamine River Watershed and Inventory Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hydroecological Modeling of the Lower Missouri River

HYDROECOLOGICAL MODELING OF THE LOWER MISSOURI RIVER Harold Johnson, Hydrologist, CERC, USGS, Columbia, Missouri, [email protected]; Robert Jacobson, Research Hydrologist, CERC, USGS, Columbia, Missouri, [email protected]; Aaron DeLonay, Ecologist, CERC, USGS, Columbia, Missouri, [email protected] Abstract: The Lower Missouri River (LMOR) has been altered in both its channel form and flow regime by channelization and upstream dams. As a result, habitat availability for many fish species has been greatly modified or lost. One fish species, the pallid sturgeon (Scaphirhynchus albus), is on the federal endangered species list. Although the habitat needs of the pallid sturgeon throughout its life cycle are poorly understood, the perceived needs of this fish are having an increasing influence on river management decisions. Current management debate addresses the tradeoff between rehabilitating channel form and altering flow regime to improve habitat. To evaluate habitat availability on the LMOR, we developed a 2-dimensional, depth-averaged hydrodynamic model of a representative 8-km reach near Boonville, Missouri. The model provides an inventory of hydraulic habitat over discharges ranging 1-99 % flow exceedance. To evaluate habitat use, we used acoustically tagged shovelnose sturgeon (Scaphirhynchus platorynchus), a closely related species to the pallid sturgeon. Hydroacoustic maps of depth, velocity, and substrate at fish locations provide objective measures of habitat use. Results indicate that adult sturgeon select areas with high gradients of depth and velocity, typically found in wakes downstream of wing dikes and along steep banks and margins of sandbars. Using these criteria, the 2-d model results can be evaluated to map the occurrence of selected wake habitat. -

Missouri Conservationist, August 2007

Missouri ConservationistVolume 68, Issue 9, sePTemBeR 2007 •Serving nature & You [Note to our readers] Answering the Call or as long as I can remember, Conservation department employees have assisted in emergency situations. staff have Ftaken action to rescue drowning, choking and accident victims. The Department and its staff are also ready to step up when natu- watercraft, firearms and other specialized equipment. Safety ral disasters strike. equipment and gear are mandated. Accidents are reviewed to After Hurricane Katrina in the fall of 2005, the Department determine how they can be avoided in the future. With the spe- answered the call for help. Sixteen conser- cialized skills of Conservation employees, vation agents and agent supervisors, with it isn’t surprising that the Department of eight boats, went to New Orleans. Search Public Safety asked us to take a much and rescue was their top priority. larger role in managing Missouri’s emer- Severe spring storms in 2006 gency response and recovery if a natural brought significant destruction to south- or technological catastrophe occurs. east Missouri. The Department aided Severe winter weather in early 2007 with both staff and equipment. Teams created an “opportunity” for us to use assisted with road cleanup and county- the Incident Command Team concept. damage assessment, and agents provided With power outages affecting thousands security detail. and massive debris blockages in several About this time, all Missouri state counties, the Department and other state agencies incorporated the National agencies quickly joined SEMA’s efforts. Incident Management System (NIMS). After severe winter weather in early Conservation employees opened roads NIMS provides a consistent approach 2007, Department employees cleared for emergency vehicles and the National for federal, state and local governments access to power lines and roads. -

Missouri Conservationist December 2020

VOLUME 81, ISSUE 12, DECEMBER 2020 MISSOURI SERVING NATURE & YOU CONSERVATIONIST MISSOURI DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION MISSOURI DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION November/December 2020 January/February 2020 MISSOURI DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION July/August 2020 ANIMAL ASSASSINS THEY AIM FOR PREY THE BOING INSPIRE SOME ANIMALS TAKE ! LEAPING TO NEW LENGTHS CHILDREN MISSOURI DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION MISSOURI DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION Septem ber/October 2020 FLOWER BEES STAY BUZZYPOWER GATHERING IN YOUR LIFE POLLEN AND NECTAR March/Apri l 2019 MISSOURI DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION TO GET SAY OUTSIDE WHA ANIMALS DO SOME Ju ly/Au gu st 2 01 9 FUNNY THINGS T? WINTER IS COMING AND CRITTERS KNOW HOW TO COPE WITH THE COLD NO SHAD Looking for a way to coax your kids ON THEE GLADE LIFE ’S HOT IN MISSOURI to unplug, climb off the couch, and MINI DESERTS ’S get outside? Then check out Xplor, the Conservation Department’s free Don t keep the door magazine for kids and kids at heart. ’ closed any longer. Six times a year, Xplor serves up eye- popping art, photos, and stories about Subscribe online at Missouri’s coolest critters, niftiest natural mdc.mo.gov/xplor. places, and liveliest outdoor activities. The magazine is free to Missouri residents (one subscription per household, please). Out-of-state subscribers pay $5 per year; out-of-country subscribers pay $8. MISSOURI DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION MISSOURI CONSERVATIONIST DECEMBER 2020 Contents VOLUME 81, ISSUE 12 10 ON THE COVER Bald eagles fly over the Mississippi River : NOPPADOL PAOTHONG 500mm +2.0x teleconverter f/8, 1/640 sec, ISO 800 GOVERNOR Michael L. -

Rock Island Trail Opportunity Analysis Infrastructure That Strengthens Communities

Rock Island Trail Opportunity Analysis Infrastructure that Strengthens Communities Prepared by Pat Curry and Martha Bass University of Missouri Extension Contact [email protected], 573.882.9509 October 2018 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................3 Introduction and Background ....................................................................................6 Trail Oriented Outdoor Recreation Statistics ............................................................7 Community Engagement ...........................................................................................9 Community Impacts of Trails Literature Review........................................................10 Property Values ......................................................................................................12 Public Health ..........................................................................................................13 Business Development ...........................................................................................13 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan ................................................14 Analysis of Public Comments .....................................................................................16 Profile of Trail Communities ......................................................................................25 Missouri’s Experience with the Katy Trail ..................................................................28 -

3. Community Facilities and Services

Appendix A 3. Community Facilities Background Information and Services INTRODUCTION Community facilities and services are required to support the functions of the community and any potential new development. These include such necessities as utilities, public safety, parks and recreation, and general governmental services. These services are supplied by County Government, municipalities, special districts, and utilities in order to enhance the overall quality of life. The rapid growth of St. Charles County has been paralleled by increased demand for public facilities and services. The timely provision of these is a critical part in making the county an attractive place for businesses and residents alike. This chapter reviews the service capabilities of water and sanitary sewer service providers, the service areas for various utilities, fire protection and emergency medical service (EMS) agencies, law enforcement, park and recreational opportunities, and County health services. Social service organizations operating within the county are also reviewed, including the services provided by these agencies, the populations served, and the future services to be offered. WATER SERVICE The water service area map depicts the water service areas of various municipalities, Missouri American Water Company, and Public Water Supply District No. 2 (PWSD2) of St. Charles County. The largest geographical service area is that of Public Water Supply District No. 2 covering sections of both St. Charles and Warren Counties. This district provides service in St. Charles County generally south of Interstate 70 from the area along Route K west to the Warren County line, and south and east to the Missouri River. The district provides service to the cities of Foristell, Lake Saint Louis, New Melle, and Augusta, and portions of the cities of Dardenne Prairie, O’Fallon and Weldon Spring. -

2019 Annual Report.Indd

2019 Annual Report — KANSAS CITY AREA — ST. LOUIS AREA — OTHER STATE PARKS & HISTORIC SITES Starting in 2015, Missouri State Parks received funding from the Missouri Parks Association to encourage Missouri senior citizens to explore Missouri state parks and state historic sites. Th e name of this program is Seniors to Parks. Th e Seniors to Parks program is funded by an endowment from the Ben and Bettie Breeding family to be, “used exclusively for the establishment of an outreach project which would provide funds for the transportation, assistance and supervision of Missouri elderly and/or disabled persons for day and overnight trips to and from Missouri wildlife conservation and preservation areas and Missouri state parks.” Th is report details the successful Seniors to Parks trips that were held throughout the state in 2019. 2019 QUICK SUMMARY • 24 Total Tours • 707 Total Participants Total Budget Allocated $ 40,000.00 Amount Spent $30,387.02 Remaining Balance $9,612.98 Katy Trail State Park Kansas City Area “Rock Island Spur” 22 participants 8 total trips 242 total participants Seniors toured the Rock Island Spur at Katy Trail State Park by bus, exploring the gently sloping 193 fi rst time participants farmland and woodlands. Tour participants viewed an abundance of recreation and wildlife, while an Bruce R. Watkins Cultural Heritage Center interpreter provided history of the area and Rock “Jazz Storytellers” Island Line, as well as education on local natural 83 participants resources. Seniors joined us at Bruce R. Watkins Cultural Center for a performance by the Jazz Storytellers. Watkins Woolen Mill State Historic Site Th e Jazz Storytellers featured an internationally renowned cast including vocalist Lisa Henry, “A Step Back in Time” storyteller Brother John Anderson, bassist Tyrone – Kansas City Parks, 20 participants Clark and drummer Mike Warren. -

Katy Trail State Park Inset City T L

S T To Kampville D CHAMP A R E 7 T D 9 E V D V To US 54 ST CHARLES L To US 67 A To Alton, IL To Harrisburg B To To Moberly To Hallsville O B R C H V V N E L W O L D W ?> F I US 63 Y AIRPORT O B L T A WEST Missouri Department of Transportation E V PRATHERSVILLE RD W OP94 K G ATKINS ?>P E C [£ N R 67 ALTON A C E ST LOUIS H H PARK E O SAINT S W A N F COLUMBIA L ?>M M IE S W E ?>B E D FORT BELLE £ D U TH A R [63 R Y D PAUL D R H S R ! E R AREA AU R R L T Y E H E P A Highways and Transportation Commission 573-751-2824 P O LE T FONTAINE L B V L RO N IE B M R I R R O 763 S W RD P L L U C N O V E R ST. D D S E S S I T I R HO L D F D T CHA S OL T IL I I RLES CO C R JOSEPHVILLE T E O D A V L R JOHN GLENN To T S STANISLAUS CA D To Savannah To To King City H D ST To I-29 11 S 79 ?>C U LOUIS R P OP CO BR N OWN I O Council N E H N D I-29 ?>E D U R A MISSOURI CBD D s S 5 S O R SCHO M I OL RD W D R COLUMBIA V D S O F S Michael T. -

Source to Tap: a History of Missouri's Public Water Supplies

Source to Tap: A History of Missouri’s Public Water Supplies By: Loring Bullard © 2010 Watershed Press Design by: Kelly Guenther Source to Tap: A History of Missouri’s Public Water Supplies By: Loring Bullard Introduction To their great benefit, most Missourians have access to At some point in time, citizens in adequate supplies of clean, safe drinking water. Nearly almost every city realized that public nine out of ten people in the state are served by public water would be essential to their water systems. Missouri’s four largest cities—St. Louis, community’s continuing growth and Kansas City, Springfield and Independence—have prosperity. Adequate water supplies were provided drinking water to their citizens for well over a especially good for business. Merchants hundred years, and most of the state’s cities have enjoyed and manufacturers pushed for public public water for over three-quarters of a century. Like the water supplies because they saw the communities that fostered them, these water systems have positive effects, such as the expansion of grown and evolved over the years, reflecting technological industry, on cities that had obtained advancements and the changing expectations of them. In 1875, when Springfield’s civic customers. Today it easy for Missourians, like other leaders solicited proposals for a Americans, to take their safe, readily available water waterworks (a term used to describe all supplies for granted. the built components of a water system—pipes, pumps, reservoirs, tanks, filter plants, etc.), a newspaper editorial noted the “universal experience” that cities which had established waterworks moved ahead, “while their sisters, with other advantages equal, were rapidly going to decay.”1 Naturally, people were concerned about the purity of their city’s water source, especially since the early water- works employed little in the way of water treatment as we know it today. -

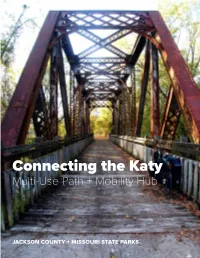

Connecting the Katy Multi-Use Path + Mobility Hub

Connecting the Katy Multi-Use Path + Mobility Hub JACKSON COUNTY + MISSOURI STATE PARKS Cover Letter from Missouri Governor Michael L. Parson 2 Project Description 6 Project Location 22 Project Funding 24 Merit Criteria 26 Project Readiness 30 Appendix A: Benefit Cost Analysis Appendix B: Letters of Support Connecting the Katy Quick Facts Project Type: Multi-Use Path Project Length: 6.85 MI. + 550’ Bridge Urban or Rural: Rural Congressional District(s): MO-4, MO-5 Project Cost: $ 11,441,460 Grant Request: $ 11,049,960 “Where the Tracks Meet the Trail” Missourians are a collaborative bunch. When Pleasant Hill realized that Missouri State Parks would be extending the Katy Trail along the old Chicago, Rock Island, & Pacific Railway from Windsor, Missouri to the Cass County Fairgrounds, the city didn’t hesitate to start building trail connections through their town. Multiple phases of the “MOPAC” trail and the cycle track pictured above were built to connect to the Rock Island Spur of the Katy Trail. These already completed facilities will be critical to Connecting the Katy to the Kansas City Region. Project Description BACKGROUND At 240 miles the Katy Trail is the longest Rails-to- to Kansas City, opening the entire state to the benefits of Trails project in the country, stretching across Missouri this fantastic asset. from Clinton to Saint Louis. For nearly three decades, An economic powerhouse for the State of Missouri, the advocates in Western Missouri have been searching for a Katy Trail sees over 400,000 users per year and generates way to connect this trail to Kansas City, thereby creating over $18 Million in economic activity. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G4127 NORTHWESTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G4127 FEATURES, ETC. .C8 Custer National Forest .L4 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail .L5 Little Missouri River .M3 Madison Aquifer .M5 Missouri River .M52 Missouri River [wild & scenic river] .O7 Oregon National Historic Trail. Oregon Trail .W5 Williston Basin [geological basin] .Y4 Yellowstone River 1305 G4132 WEST NORTH CENTRAL STATES. REGIONS, G4132 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .D4 Des Moines River .R4 Red River of the North 1306 G4142 MINNESOTA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G4142 .A2 Afton State Park .A4 Alexander, Lake .A42 Alexander Chain .A45 Alice Lake [Lake County] .B13 Baby Lake .B14 Bad Medicine Lake .B19 Ball Club Lake [Itasca County] .B2 Balsam Lake [Itasca County] .B22 Banning State Park .B25 Barrett Lake [Grant County] .B28 Bass Lake [Faribault County] .B29 Bass Lake [Itasca County : Deer River & Bass Brook townships] .B3 Basswood Lake [MN & Ont.] .B32 Basswood River [MN & Ont.] .B323 Battle Lake .B325 Bay Lake [Crow Wing County] .B33 Bear Head Lake State Park .B333 Bear Lake [Itasca County] .B339 Belle Taine, Lake .B34 Beltrami Island State Forest .B35 Bemidji, Lake .B37 Bertha Lake .B39 Big Birch Lake .B4 Big Kandiyohi Lake .B413 Big Lake [Beltrami County] .B415 Big Lake [Saint Louis County] .B417 Big Lake [Stearns County] .B42 Big Marine Lake .B43 Big Sandy Lake [Aitkin County] .B44 Big Spunk Lake .B45 Big Stone Lake [MN & SD] .B46 Big Stone Lake State Park .B49 Big Trout Lake .B53 Birch Coulee Battlefield State Historic Site .B533 Birch Coulee Creek .B54 Birch Lake [Cass County : Hiram & Birch Lake townships] .B55 Birch Lake [Lake County] .B56 Black Duck Lake .B57 Blackduck Lake [Beltrami County] .B58 Blue Mounds State Park .B584 Blueberry Lake [Becker County] .B585 Blueberry Lake [Wadena County] .B598 Boulder Lake Reservoir .B6 Boundary Waters Canoe Area .B62 Bowstring Lake [Itasca County] .B63 Boy Lake [Cass County] .B68 Bronson, Lake 1307 G4142 MINNESOTA. -

Klenklen Bridge HAER No. M0-91 Spanning the Lamine River at County Road 223 Vicinity of Pleasant Green Cooper County Missouri PH

Klenklen Bridge HAER No. M0-91 Spanning the Lamine River at County Road 223 Vicinity of Pleasant Green Cooper County Missouri \ PHOTOGRAPHS HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS Historic American Engineering Record National Park Service Rocky Mountain Regional Office P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225-0287 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD KLENKLEN BRIDGE HAER No. M0-91 Site Location: Spanning the Lamine River at County Road 223; 4.3 miles northwest of Pleasant Green; southwest quarter of Section 20, Township 47 North, Range 19 West; Cooper County, Missouri. USGS quadrangle: Clifton City, Missouri (7\-Minute series) Present Owner: Cooper County, Missouri Present Use: closed (scheduled for demolition in 1996) Present Condition: partially collapsed Construction Date: September 1929 - April 1930 Designer: R. T. Faith, Calhoun, Missouri J.A. Dice, Warsaw, Missouri Builder: J.A. Dice, Warsaw, Missouri Significance: Bridge builder J.A. Dice (1866-1947] built over thirty wire suspension bridges between 1895 and 1940 in central Missouri. Ten of these remain in place today with varying degrees of physical integrity. As a group, these spans comprise the state's most important exam ples of vernacular bridge construction, designed and built without benefit of detailed structural analysis. Dice built his suspension spans empirically using easily obtained materials and hand labor, and, as a result, they cost substantially less than comparable steel truss spans. They were strikingly lightweight, however, and have fared poorly in subsequent years. Before its recent structural failure, the Klenklen Bridge was distinguished as one of the best-preserved of the remaining Dice-built bridges. It is still an excellent example of an esoteric structural type-among Missouri's most technologically noteworthy spans from the inter-war period. -

Katy Trail State Park Collection (CA6007)

PRELIMINARY INVENTORY ACCESSION CA6007 KATY TRAIL STATE PARK COLLECTION This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri, Research Center- Columbia. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Dates: 1980s-1990s Creator: Hindman, Darwin, collector Collection Size: 13.4 cubic feet, 2 audio cassettes Introduction Addition of materials concerning the creation and development of the Katy Trail State Park. Includes legal documents, newspaper clippings, promotional materials, and correspondence. NOTE: See also Katy Trail State Park Collection (C0003). Box List Box 1 General Research Lawsuit Box 2 Lawsuit Endorsements Tourism Economics- Biking Economics- Walking Anheuser-Busch Agendas Trail Studies Events Spring Fun Fest Auto Tour St. Charles Rally Other Volunteer Volks March Adjacent Land- Effect on Minnesota Study Adjacent Land Owners- Study Kansas Thesis S- Bill Lockwood Pol. Rail Banking Trails Planning Construction Standards History Publications Rhineland: Winter in a Missouri Rivertown From Rails to Trails THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION 4/29/2020 ACCESSION CA6007 KATY TRAIL STATE PARK COLLECTION National Geographic Traveler A Guide to America’s Rail-Trails Railroads Recycled Indians and Archaeology of Missouri World Watch Paper 90: The Bicycle: Vehicle for a Small Planet Katy Trail: Jefferson City to Boonville Box 3 Publications The Uncorrupted Heart: Journal and Letters of Frederick Julius Gustorf Report on a Journey to the Western States of North America Paths of Resistance: Tradition and Dignity in Industrializing Missouri Early Midwestern Travel Narratives Our Missouri National Geographic Traveler Changes in the Channel of the Lower Missouri River and Effects on Fish and Wildlife Missouri Historical Review Maps Newspaper Clippings/Brochures Katy Trail Openings St.