Tops to Lakes Initiative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1994 HBOC Bird Report

HUNTER REGION OF NEW SOUTH WALES ANNUAL BIRD REPORT Number 2 (1994) ISSN 1322-5332 Photo here Produced by Hunter Bird Observers Club Inc HUNTER REGION OF NSW 1994 BIRD REPORT This annual record of the birds of the Hunter Region of NSW has been produced by the Hunter Bird Observers Club Inc (HBOC). The aims of HBOC are to: • Encourage and further the study and conservation of Australian birds and their habitat; • Encourage bird observing as a leisure time activity. HBOC holds monthly meetings and organises regular outings and camps. Beginners and more experienced birdwatchers are equally catered for in the range of activities that are provided by the Club. Members receive a newsletter every two months, and have access to HBOC's comprehensive range of books, tapes, compact discs and video cassettes about Australian and world birdlife. The membership categories are single, family and junior, and applications for membership are welcomed at any time. Copies of this report, at $10.00 each plus $1.50 (for 1-3 copies) for postage and handling, may be obtained from: The Secretary Hunter Bird Observers Club Inc. P.O. Box 24 New Lambton NSW 2305 Cover photograph: to be advised (Photographer: Gary Weber) Date of Issue: August 22 1995 ISSN: 1322-5332 © Hunter Bird Observers Club Inc CONTENTS Page FOREWORD INTRODUCTION 1 HIGHLIGHTS OF THE YEAR 3 SYSTEMATIC LIST 4 Introduction 4 Birds 5 ESCAPEES 48 LOCATION ABBREVIATIONS 48 UNCONFIRMED RECORDS 49 OBSERVER CODES 50 APPENDIX – THE HUNTER REGION FOREWORD In introducing the second annual Bird Report of the Hunter Bird Observers Club I would like firstly to congratulate members of the club who responded so willingly to the idea of sending in observations for possible publication. -

The History of the Worimi People by Mick Leon

The History of the Worimi People By Mick Leon The Tobwabba story is really the story of the original Worimi people from the Great Lakes region of coastal New South Wales, Australia. Before contact with settlers, their people extended from Port Stephens in the south to Forster/Tuncurry in the north and as far west as Gloucester. The Worimi is made up of several tribes; Buraigal, Gamipingal and the Garawerrigal. The people of the Wallis Lake area, called Wallamba, had one central campsite which is now known as Coomba Park. Their descendants, still living today, used this campsite 'til 1843. The Wallamba had possibly up to 500 members before white contact was made. The middens around the Wallis Lake area suggest that food from the lake and sea was abundant, as well as wallabies, kangaroos, echidnas, waterfowl and fruit bats. Fire was an important feature of life, both for campsites and the periodic 'burning ' of the land. The people now number less than 200 and from these families, in the main, come the Tobwabba artists. In their work, they express images of their environment, their spiritual beliefs and the life of their ancestors. The name Tobwabba means 'a place of clay' and refers to a hill on which the descendants of the Wallamba now have their homes. They make up a 'mission' called Cabarita with their own Land Council to administer their affairs. Aboriginal History of the Great Lakes District The following extract is provided courtesy of Great Lakes Council (Narelle Marr, 1997): In 1788 there were about 300,000 Aborigines in Australia. -

(Phascolarctos Cinereus) on the North Coast of New South Wales

A Blueprint for a Comprehensive Reserve System for Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) on the North Coast of New South Wales Ashley Love (President, NPA Coffs Harbour Branch) & Dr. Oisín Sweeney (Science Officer, NPA NSW) April 2015 1 Acknowledgements This proposal incorporates material that has been the subject of years of work by various individuals and organisations on the NSW north coast, including the Bellengen Environment Centre; the Clarence Environment Centre; the Nambucca Valley Conservation Association Inc., the North Coast Environment Council and the North East Forest Alliance. 2 Traditional owners The NPA acknowledges the traditional Aboriginal owners and original custodians of the land mentioned in this proposal. The proposal seeks to protect country in the tribal lands of the Bundjalung, Gumbainggir, Dainggatti, Biripi and Worimi people. Citation This document should be cited as follows: Love, Ashley & Sweeney, Oisín F. 2015. A Blueprint for a comprehensive reserve system for koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) on the North Coast of New South Wales. National Parks Association of New South Wales, Sydney. 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Traditional owners ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Citation ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Great Lakes Local Flood Plan

Great Lakes December 2011 To be reviewed no later than December 2013 GREAT LAKES LOCAL FLOOD PLAN A Sub-Plan of the Great Lakes Local Disaster Plan (DISPLAN) CONTENTS CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................................................ I LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................................ II DISTRIBUTION LIST .........................................................................................................................................III AMENDMENT LIST ......................................................................................................................................... IV LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................. V GLOSSARY ..................................................................................................................................................... VII PART 1 - INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Authority ......................................................................................................................................... -

BIRDING LOCATIONS of the LOWER MID NORTH COAST

BIRDING LOCATIONS of the LOWER MID NORTH COAST Including the Lower MANNING VALLEY surrounding TAREE and the Regent Bowerbird WALLIS LAKE area around FORSTER / TUNCURRY 2017 edition Prepared By Manning Great Lakes Birdwatchers Inc. THE LOWER MID NORTH COAST The Lower Manning Valley surrounding Taree and the Wallis Lake area around Forster / Tuncurry are each a paradise for birdwatchers. Numerous National Parks, State Forests and Nature Reserves contain a variety of natural vegetation types including rainforest, woodland, coastal heath and tidal estuaries hosting many species of birds. The Lower Mid North Coast is fringed by endless kilometres of white sandy beaches, crystal clear waters and rugged cliffs providing many opportunities to view seabirds as well as dolphins and whales. Visitors will enjoy easy access to most areas by conventional vehicles, with 4 wheel drive(s) tracks available for the more adventurous. Many species of waterbirds, bushbirds and raptors, including nests, can be viewed along the pristine waterways of The Manning River or Wallis Lake. Regular cruises are available and small self-skippered boats can be hired. Accommodation is available to cater for all needs. The list includes the land and freshwater birds reliably recorded in the Manning Valley and Great Lakes are as well as the common seabirds to be seen from the coast. Some have been seen only once or a few times in recent years, or are known now only from a small area while others can be seen any day in appropriate habitat. Any unusual sightings or suggestions regarding this brochure may be forwarded to the address below and would be greatly appreciated. -

Vegetation and Flora of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve, Lower North Coast of New South Wales

645 Vegetation and flora of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve, lower North Coast of New South Wales. S.J. Griffith, R. Wilson and K. Maryott-Brown Griffith, S.J.1, Wilson, R.2 and Maryott-Brown, K.3 (1Division of Botany, School of Rural Science and Natural Resources, University of New England, Armidale NSW 2351; 216 Bourne Gardens, Bourne Street, Cook ACT 2614; 3Paynes Lane, Upper Lansdowne NSW 2430) 2000. Vegetation and flora of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve, lower North Coast of New South Wales. Cunninghamia 6(3): 645–715. The vegetation of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve on the lower North Coast of New South Wales has been classified and mapped from aerial photography at a scale of 1: 25 000. The plant communities so identified are described in terms of their composition and distribution within Booti Booti NP and Yahoo NR. The plant communities are also discussed in terms of their distribution elsewhere in south-eastern Australia, with particular emphasis given to the NSW North Coast where compatible vegetation mapping has been undertaken in many additional areas. Floristic relationships are also examined by numerical analysis of full-floristics and foliage cover data for 48 sites. A comprehensive list of vascular plant taxa is presented, and significant taxa are discussed. Management issues relating to the vegetation of the reserves are outlined. Introduction The study area Booti Booti National Park (1586 ha) and Yahoo Nature Reserve (48 ha) are situated on the lower North Coast of New South Wales (32°15'S 152°32'E), immediately south of Forster in the Great Lakes local government area (Fig. -

Introduction the Need for New Reserves

Koala Strategy Submissions, PO Box A290, Sydney South NSW 1232, [email protected] CC. [email protected] 2nd March 2017. NPA SUBMISSION: WHOLE OF GOVERNMENT KOALA STRATEGY; SAVING OUR SPECIES DRAFT STRATEGY AND REVIEW OF STATE ENVIRONMENT PLANNING POLICY 44—KOALA HABITAT PROTECTION Introduction The National Parks Association of NSW (NPA), established in 1957, is a community-based organisation with over 20,000 supporters from rural, remote and urban areas across the state. NPA promotes nature conservation and evidence- based natural resource management. We have a particular interest in the protection of the State’s biodiversity and supporting ecological processes, both within and outside of the formal conservation reserve system. NPA has a long history of engagement with both government and non-government organisations on issues of park management. NPA appreciates the opportunity to comment on the whole of government koala strategy (the strategy), the Saving Our Species iconic koala project (the SOS project) and the Explanation of intended effect: State Environment and Planning Policy 44 (Koala Habitat Protection) (SEPP 44). Please note, NPA made a submission on SEPP 44 in late 2016 prior to the deadline being extended which we have reattached at the end of this document (Appendix 1). NPA was also consulted on the SOS programme in August 2016, which we greatly appreciated. We provided OEH with feedback on the programme at that time, which also contained an exploration of issues facing koalas, which we have reattached in Appendix 2. NPA has had significant input to the development of the Stand Up For Nature (SUFN) submission to this consultation. -

Tracker 165111 - 'Gigi' - Adult Male Straw-Necked Ibis

Tracker 165111 - 'Gigi' - Adult male straw-necked ibis Bowra r Narkoola e Wondul Range v i R WARWICK e 12 Mile n Weir River n er lo iv a R B r yre River Maryland ei Macint er W iv ol R do Riv a n er o lla Girraween lg a er Dthinna Dthinnawan Binya u B iv Culgoa Floodplain C R Sundown r i Maroomba er e m Burral Yurrul Culgoa v iv o i o R B R n Kwiambal r a a Torrington e r rr Bunnor Westholme Ledknapper iv a a Arakoola R h N k Gwydir Wetlands Bullala Capoompeta ie o Warrambool Severn River rr B MOREE Butterleaf Bi Kings Plains Warialda Narran Lake Kirramingly INVERELL Barwon er B Bingara Guy Fawkes River iv og er Gwydir River R an n Riv Single Warra g R Barwo Moema lin i v !! G ar e River !! D r oi Killarney The Basin a Nam r a Toorale Mount Kaputar Ironbark ! R Ginghet Gilwarny i v ARMIDALE e ! r Gundabooka Pilliga West Leard Warrabah ! C 09/03/2017 ! a ! Macquarie Marshes s t ! Cunnawarra l ! ! e Merriwindi Pilliga East r !!29/10/2016 e P !! a GUNNEDAH ! ! e g Pilliga e Oxley Wild Rivers 06/11/2016 h l 07/11/2016!! Yarragin ! R !! R Wondoba iv ! 04/11/2016 Ukerbarley e i r v !! M e Warrumbungle r 08/03/2017 TAMWORTH ! a ! c Trinkey Mummel Gulf ! q ! u Binnaway ! a Nowendoc ! r Biddon 03/11/2016 ! ie Ben Halls GapCurracabundiBretti ! ! R ! ! i Weetalibah Quanda ve Coolah Tops ! Woko r Breelong Towarri ! Drillwarrina 11/02/2017 ! ! ! Goonoo ! !!!!!Camerons Gorge Copeland Tops CoolbaggieCobbora ! 07/03/2017! Barrington Tops Durridgere DUBBO The Glen Balowra ! Manobalai Mount Royal Dapper Bedooba ! Beni Yarrobil Myall Lakes Goulburn River -

Context Statement for the Gloucester Subregion, PDF, 11.22 MB

Context statement for the Gloucester subregion Product 1.1 from the Northern Sydney Basin Bioregional Assessment 28 May 2014 A scientific collaboration between the Department of the Environment, Bureau of Meteorology, CSIRO and Geoscience Australia The Bioregional Assessment Programme The Bioregional Assessment Programme is a transparent and accessible programme of baseline assessments that increase the available science for decision making associated with coal seam gas and large coal mines. A bioregional assessment is a scientific analysis of the ecology, hydrology, geology and hydrogeology of a bioregion with explicit assessment of the potential direct, indirect and cumulative impacts of coal seam gas and large coal mining development on water resources. This Programme draws on the best available scientific information and knowledge from many sources, including government, industry and regional communities, to produce bioregional assessments that are independent, scientifically robust, and relevant and meaningful at a regional scale. The Programme is funded by the Australian Government Department of the Environment. The Department of the Environment, Bureau of Meteorology, CSIRO and Geoscience Australia are collaborating to undertake bioregional assessments. For more information, visit <www.bioregionalassessments.gov.au>. Department of the Environment The Office of Water Science, within the Australian Government Department of the Environment, is strengthening the regulation of coal seam gas and large coal mining development by ensuring that future decisions are informed by substantially improved science and independent expert advice about the potential water related impacts of those developments. For more information, visit <www.environment.gov.au/coal-seam-gas-mining/>. Bureau of Meteorology The Bureau of Meteorology is Australia’s national weather, climate and water agency. -

Taree Regional Bus Timetable

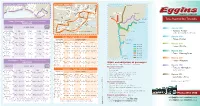

D R E YN O PEA S B RSO T M E N E D PL O P S E PO L C A T I T R R R GU E BE E M D T LB A O C D O T H C S UR O L NE M E D T S R T T R P E IV O E N B I B L A S U T NS T KY ET INDUSTRIAL ROAD AV H S S S G A IM D G A L E T P C N R L T R M RUSHBO I C X C B UN R T A L T M T S D L CL B A R L S F O S L A E E VIE A E IN W W TT A E G T T Y C Y ST S HARRINGTON ROAD N A to Taree K A E P L L U W L R O AV C A E H E O T E C E L O R K I L R T L M S S A T L O Z HARRINGTON - Route 320 WINGHAM - RouteE 319 ZA K R R M M C O R IN S O Lansdowne I VE I I D RI C N NT A IM A A D E R LATHAM AVE L R O R M R P REGIONAL MAP P ST S D O S F L O E N C T D T U E L R AL DA M R K T N R R L I C A S B A T K E Y N M A G A O S A S S P H N T NT P I L IM E L R H T SCOTT ST E T C T R S REE GRANTER ST S T T ST T C R R S R I IR N V E S IV E IN E E E R E U KE R T E H ST O B ST Q CH S N T G H A M BLVD N TT Y T PHINE Y A JOSE S RO PRICE NICHOLSON ST T S N L U R E W T ST E T R L E COODE ST E S S S T L T I E S S GLACKEN ST E E A B L BE Y CROWDY ST B BELL N T LL M L N A ST P T E S E INED B A BEACH ST D S T COMB MURRAY ST A L EAST Coopernook A S Taree O M ELE PILOT ST CL Y R CT B C RA O FA W U PD UN M RQ E TR UH O see Taree Timetable A A A Y R C R H L C ST UB D P R N D D OXLEY STREET E E R V CALEDONIA STREET E L E E CA Wingham B K NG U ST FA H ET RQ R N Q T UH T N A U E R BEACH STREET U S B O T ST B V B A R Harrington A W T N ILL Taree Regional Bus Timetable H IA O M S S S FO T P TH L ER N M I ING D A T HA A Taree to Harrington via Coopernook & Cundletown S M T R S ROAD S B K L UCESTER -

17 Croft & Leiper

ASSESSMENT OF OPPORTUNITIES FOR INTERNATIONAL TOURISM BASED ON WILD KANGAROOS By David B Croft and Neil Leiper WILDLIFE TOURISM RESEARCH REPORT SERIES: NO. 17 RESEARCH REPORT SERIES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The primary aim of CRC Tourism’s research report series is technology transfer. The reports are targeted toward both industry and government users and tourism Objectives researchers. The content of this technical report series primarily focuses on applications, but may also advance research methodology and tourism theory. The report series titles relate to CRC Tourism’s research program areas. All research The first objective of this study was to identify various places in reports are peer reviewed by at least two external reviewers. For further information Australia where tourists can have direct experiences of macropods in on the report series, access the CRC website, [www.crctourism.com.au]. a natural habitat, and to assess the likely quality of such an experience. This was achieved by formal inquiry from wildlife Wildlife Tourism Report Series, Editor: Dr Karen Higginbottom researchers and managers with an interest in the kangaroo family, and This series presents research findings from projects within the Wildlife Tourism through analysis of the distribution and biology of species. This part Subprogram of the CRC. The Subprogram aims to provide strategic knowledge to of the study identified 16 important sites in New South Wales, facilitate the sustainable development of wildlife tourism in Australia. Queensland and Victoria for assessment of the feasibility of kangaroo- based tourism. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data The second objective was to review this set of sites for developing Croft, David B. -

Report I Great Lakes Council 2011 State of the Environment Report

Great Lakes Council 2011 Stat E of thE EnvironmEnt Re port Great Lakes Council 2011 State of the Environment Report i Great Lakes Council 2011 State of the Environment Report Prepared by: Great Lakes Council Natural Systems and Estuaries Section Enquires should be directed to: Great Lakes Council Po Box 450 forster NSW 2428 telephone: (02) 6591 7222 fax: (02) 6591 7221 email: [email protected] © 2011 Great Lakes Council Contents 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................1 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................10 Contents 3 Water .............................................................................................................................14 3.1 Water quality ...........................................................................................................................................................14 Wallis Lake ..........................................................................................................................................................22 Mid Wallamba Estuary ...................................................................................................................................24 Pipers Creek .......................................................................................................................................................26 Wallis Lake ..........................................................................................................................................................28