GAPS, GHOSTS and GAPLESS RELATIVES in SPOKEN ENGLISH1 Chris Collins, New York University Andrew Radford, University of Essex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Look Good, Do Good

24 Daily Express Monday July 11 2016 Picture: SWNS 11 th July – 18th July Offer ends 10am Monda Jail for bigamist y 18th July Garden Rocking Chair who stole from new wife’s family A CONMAN who stole from his new By Dan Townend wife’s family soon after getting mar- ried has been jailed... for bigamy. work and discovered he was still mar- Mitchell Sharpe, 44, had previously ried to another woman. been involved in divorce proceedings Sharpe, of Chaddesden, Derby, but there was never a decree abso- admitted bigamy and was jailed for WAS £79.99 lute, so that marriage never ended. five months at Derby Crown Court on HALF He met Lisa Buckingham, 39, on Friday. His current partner broke NOW £39.99 an online dating site and whisked her down in tears in the public gallery and PRICE Plus £4.95 P&P off on holiday to Portugal where he he mouthed “I love you” to her as he proposed to her in March 2014. was sent down. He will serve half of Lisa Buckingham and Sharpe on their wedding day He deliberately lied to her about his his sentence before being released on www.shop.express.co.uk previous marriage, Jonathan Wigodes, licence. prosecuting said. But two days after Judge Jonathan Bennett said: “The the wedding, Lisa received a Face- main issue is the issue of deceit both book message from another woman to the register office and to the vic- saying: “Good luck with that cocaine tim. I don’t accept that in effect this conman”, a court heard. -

Beauty Is Only Skin-Deep, but So Was This Film

10 1G T Wednesday August 14 2019 | the times television & radio Beauty is only skin-deep, but so was this film Burke’s bugbear, understandably, is popularised “heroin chic”. “You have Chris the obscene beauty standard foisted to look at fashion as fantasy — what on women by Love Island, Instagram you are seeing in a magazine is not and the like, jostling more and more real,” were his weasel words. These Bennion young people into therapy or under things look pretty real — in the knife. She began with a visit to the magazines, on television, on social Love Island alumna Megan Barton- media — to teenage girls. Burke said TV review Hanson, a woman not afraid of that heroin chic was “repulsive”. But scalpels. “I don’t want young girls to she said it to the camera, not Rankin. have unrealistic expectations,” said An opportunity missed. Barton-Hanson, a walking unrealistic Beauty is only skin-deep was the expectation. Burke frowned. message Burke kept falling back on, Would a visit to a different idea of but everywhere she turned there were feminine beauty help? Burke has a lot young women desperate to conform to of time for Sue Tilley, the model for a homogenised physical ideal. Burke’s Lucian Freud’s 1995 painting Benefits well-meaning film, alas, was skin-deep Kathy Burke’s All Woman Supervisor Sleeping, a woman entirely too, amounting to an hour of fretting Channel 4 comfortable with her “magnificent and beautifully phrased Burkeisms. {{{(( piles of flesh”. Freud, said Tilley, “Where does this insecurity come Inside the Factory thought that libraries should be from?” Burke asked. -

Pick of the Day Radio

PICK OF THE DAY BBC1 BBC2 ITV 1 CHANNEL 4 FIVE 6.00 Breakfast (T) 20315294 6.00 CBeebies 28749 7.00 6.00 GMTV (T) 3875836 9.25 6.10 Planet Cook (T) (R) 6.00 Milkshake! 22206687 QI 9.15 Animal 24:7 (T) 1360107 CBBC 53010 8.30 CBeebies The Jeremy Kyle Show (T) 1207720 6.30 Yo Gabba 9.15 The Wright Stuff (T) 9.30pm, BBC1 10.00 Homes Under The 94752039 11.10 The 1384403 10.30 This Morning Gabba (T) (R) 43403 7.00 4020107 10.45 Trisha Hammer (T); BBC News; Flintstones Fred sneaks off to (T) 28720 12.30 Loose Freshly Squeezed 76229 7.30 Goddard (T) (R) 5685687 Weather (T) 88010 11.00 play cards. (T) (R) 2766671 Women (T) 87403 1.30 ITV Everybody Loves Raymond 11.45 Medical Investigation Living Dangerously (T) 12.00 Daily Politics (T) 97671 News; Weather (T) 79901045 (T) (R) 6186687 7.55 Frasier (T) (R) 8451478 12.35 Five 2755565 11.45 Cash In The 12.30 Working Lunch (T) 1.55 Regional News (T) (T) (R) 2180316 9.00 Will & News (T) 32130229 12.50 Attic (T); BBC News; Weather 26671 1.00 Open House (T) 89580381 2.00 Dickinson’s Grace (T) (R) 75403 9.30 Nice House, Shame About (T) 600590 12.15 Bargain (R) 73132 1.30 Live Snooker: Real Deal David Dickinson Friends (T) (R) 30039 10.30 The Garden: Revisited (T) Hunt (T) 6905652 1.00 BBC UK Championship Coverage and the team are in Bolton, The Big Bang Theory (T) (R) (R) 32633213 1.15 Cooking News; Weather (T) 75590 of the opening sessions in the Greater Manchester, where the 71687 11.00 Ugly Betty (T) The Books (T) (R) 4486381 1.30 Regional News; Weather remaining two quarter-finals at best deal of the day is a Della (R) 91584 12.00 News (T) 1.45 Neighbours (T) 4485652 (T) 59876890 1.45 Doctors the Telford International Robbia jug bought by expert 99039 12.30 Wife Swap USA 2.15 Home And Away (T) (T) 889565 2.15 Murder, She Centre, featuring a scheduled David Hakeney for £470. -

Paper Tiger Steven Spielberg: Why My Film About the Power of the Press Is So Timely

January 7, 2018 THEATRE BOOKS HOT TICKETS INTERVIEW: THE STARS FRANCE’S NEW FROM PINTER TO PICASSO: OF MARY STUART LITERARY SENSATION WE PICK THE MUST-SEES OF 2018 PAPER TIGER STEVEN SPIELBERG: WHY MY FILM ABOUT THE POWER OF THE PRESS IS SO TIMELY CONTENTS 07.01.2018 ARTS ‘In Frankenstein, Mary Shelley 4 invented two kinds Cover story of being — an Steven Spielberg’s new film is about the press-led intelligent robot revolt against the Nixon administration. Yes, he tells and a scientist Bryan Appleyard, he is well who plays God’ aware of the modern parallels Books, page 30 6 Pop ALAMY Which of today’s hits will be tomorrow’s classics? Dan Cairns offers a guide BOOKS 34 The Sunday Times 14 30 Bestsellers Film Lead review Ridley Scott’s movie about the John Carey hails an DIGITAL EXTRAS Getty kidnapping is richly outstanding look at the rewarding, says Tom Shone creation of Frankenstein NICK DELANEY Bulletins 16 32 For the arts week ahead, and Television Fiction recent highlights, sign up for James Norton as a Russian A Freddie Mercury 20 Leila Slimani’s thriller has our Culture Bulletin. For a Jew? Louis Wise is still to be biopic, above, is just Critical list turned her into a French weekly digest of literary news, convinced by McMafia’s hero Our pick of the arts this week celebrity courted by reviews and opinion, there’s one of the year’s President Macron the Books Bulletin. Both can hot prospects. be found at thesundaytimes. 18 24 co.uk/bulletins Theatre We choose the On record 36 The two leads of Mary Stuart The latest essential releases -

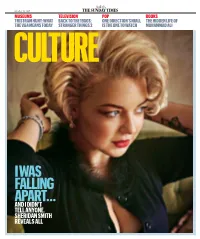

I Was Falling Apart... and I Didn’T Tell Anyone

October 15, 2017 MUSEUMS TELEVISION POP BOOKS TRISTRAM HUNT: WHAT BACK TO THE 1980S: ONE DIRECTION’S NIALL THE HIDDEN LIFE OF THE V&A MEANS TODAY STRANGER THINGS 2 IS THE ONE TO WATCH MUHAMMAD ALI I WAS FALLING APART... AND I DIDN’T TELL ANYONE. SHERIDAN SMITH REVEALS ALL CONTENTS 15.10.2017 ARTS ‘The joy of Ali was his personality, and 4 at the heart of it Cover story was playfulness’ Sheridan Smith had it all — then it very publicly went Books, page 30 awry. As the stage and TV star prepares her comeback, she reveals her pain to Dan Cairns 6 Interview IMAGES LEN TRIEVNOR/GETTY Tristram Hunt quit parliament to head the V&A. But there’s plenty more politics to face, BOOKS 34 he tells Bryan Appleyard The Sunday Times 30 Bestsellers 8 Lead review Art The first biography of Ali DIGITAL EXTRAS Thomas Ruff’s photographs since his death weighs in as never fail to intrigue, says a champion heavyweight Waldemar Januszczak Bulletins 32 For the arts week ahead, and 12 Medicine recent highlights, sign up for Dance Niall Horan is 20 Surgery was “a filthy business our Culture Bulletin. For a As anniversary celebrations the latest member Critical list fraught with hidden dangers ” weekly digest of literary news, loom, ballet’s leading lights Our pick of the arts this week until Joseph Lister pioneered reviews and opinion, there’s salute Kenneth MacMillan of One Direction hygiene and antiseptics the Books Bulletin. Both can to go solo — and be found at thesundaytimes. 24 co.uk/bulletins 14 he is storming On record 36 Film The latest essential releases Poetry The Meyerowitz Stories return America, Lisa Instagram smash: Rupi Kaur Dustin Hoffman to his Jewish Verrico discovers is the world’s bestselling poet, Instagram roots. -

UTV Media Plc Report and Accounts 2009

UTV Media plc Report and Accounts 2009 UTV Media plc Report and Accounts 2009 3 Contents n Summary of Results 5 n Chairman’s Statement 6 n Business Review 8 n Financial Review 12 n Radio GB 16 n Radio Ireland 18 n Television 20 n New Media 22 n Board of Directors 23 n Corporate Governance 24 n Corporate Social Responsibility 33 n Report of the Board on Directors’ Remuneration 40 n Report of the Directors 48 n Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities in relation to the Group Financial Statements 53 n Directors’ Statement of Responsibility under the Disclosure Transparency Rules 53 n Report of the Auditors on the Group Financial Statements 54 n Group Income Statement 56 n Group Statement of Comprehensive Income 57 n Group Balance Sheet 58 n Group Cash Flow Statement 59 n Group Statement of Changes in Equity 60 (1) n Notes to the Group Financial Statements 61 n Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities in relation to the Parent Company Financial Statements 110 n Report of the Auditors on the Parent Company Financial Statements 111 n Company Balance Sheet 113 (1) n Notes to the Company Financial Statements 114 n Registered Office and Advisers 118 (1) refer to page 4 for full listing of notes UTV Media plc 4 Report and Accounts 2009 Contents Notes to the Group Financial Statements 1: Corporate information 61 2: Summary of accounting policies 61 3: Revenue and segmental analysis 71 4: Exceptional items 74 5: Group operating costs 74 6: Auditor’s remuneration 75 7: Staff costs 75 8: Finance revenue 76 9: Finance costs 76 10: Taxation 77 11: Discontinued -

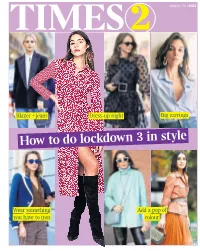

How to Do Lockdown 3 in Style

January 20 | 2021 Blazer + jeans Dress-up night Big earrings How to do lockdown 3 in style Wear something Add a pop of you have to iron colour 2 1GT Wednesday January 20 2021 | the times times2 Forget Blue Monday. It’s I knew I was February that’s the thug. An LSE study has concluded that a lot of people fib about being working class. Except this year, maybe But the assumptions others make about Carol Midgley social status are also wildly inaccurate wasn’t. “But you went to university, ow that we’re past ‘I do not miss right? I didn’t,” she said. “Just moving Blue Monday, which working in a up a few tax brackets doesn’t make you everyone knows was Those middle class. It’s an attitude, it’s the a PR brainfart garment factory’ way you do your house up, how you invented to flog ‘flawed’ handle money. I’m just like a pools holidays to shivering Sathnam Sanghera winner, a poor person who got lucky.” Ncommuters waiting murderers She doubtless had a point, but I at bus stops in the like oat milk in my coffee. I’ve think the ultimate difference between January sleet, can we turn to the The BBC has read and actively enjoyed Hilary me and people like Burchill — perhaps real culprit, the true thug of the apologised for a Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy and because immigrants and the children calendar year? I speak, obviously, of headline reading Ihave strong opinions about its of immigrants are not embarrassed February. -

Pick of the Day Radio

PICK OF THE DAY BBC1 BBC2 ITV 1 CHANNEL 4 FIVE 6.00 Breakfast (T) 93087360 6.00 CBeebies 91143 7.00 6.00 GMTV (T) 9642327 9.25 6.05 The Hoobs 8025360 6.00 Milkshake! 34150143 Criminal Justice 9.15 Helicopter Heroes (T) CBBC 26414 8.30 CBeebies The Jeremy Kyle Show (T) 6.30 The World’s Greatest 9.15 The Wright Stuff (T) 9pm, BBC1 2932360 10.00 Homes Under 790230 11.00 Schools 53872 1379389 10.30 This Morning Pop Star: Contenders 27969 3125582 10.45 Trisha The Hammer (T); BBC News; 12.00 Daily Politics (T) 91124 12.30 Loose 7.00 Freshly Squeezed 50785 Goddard (T) (R) 5287327 Weather (T) 42766 11.00 To Conference Special (T) Women (T) 61969 1.30 ITV 7.30 Everybody Loves 11.45 I Own Britain’s Best Buy Or Not To Buy (T) 2143 85872 1.00 Working Lunch News (T) 62353476 1.55 Raymond 4164105 7.55 Home 2009 (T) (R) 9975312 11.30 Cash In The Attic (T) (T) 24360 1.30 Live Snooker: Regional News; Weather (T) Frasier 9895037 8.55 Will & 12.40 Five News (T) (R); BBC News; Weather (T) The Grand Prix This 10770679 2.00 60 Minute Grace 9723105 9.30 Year Dot 41314259 12.50 Britain’s 7950872 12.15 Bargain Hunt afternoon’s first-round matches Makeover (T) 11308 3.00 The Television 64389 10.00 The Bravest (T) (R) 5914018 1.45 From Ardingly, West Sussex. at Kelvin Hall in Glasgow. (T) Alan Titchmarsh Show With Deadly Knowledge Show Neighbours (T) 7481037 2.15 (T) 8885582 1.00 BBC News; 936230 4.30 Pointless (T) guests Tommy Steele and the 29691 10.30 KNTV Sex 48853 Home And Away (T) 1339211 Weather (T) 33018 1.30 1875650 5.15 The Hairy cast of Mamma Mia! (T) 9056 11.00 Britain’s Deadliest 2.50 I Own Britain’s Best Regional News; Weather (T) Bikers’ Food Tour Of Britain 3.59 Local Weather (T) Addictions 5853 11.30 The Home: Flying Visits (T) (R) 37389940 1.45 Doctors (T) The traditional cuisine of 2688650 4.00 Midsomer Family: Teen Stories (T) 6582 9810582 3.00 FILM: Agent Of 557969 2.15 Murder, She Cornwall.