Pdfppehrc Complaint.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Meal Sites Senior Meal Sites

Find Free Food in City Council District 1 Councilmember Mark Squilla Food & Meal distribution made possible by: Philabundance, Philadelphia Corporation for the Aging, School District of Philadelphia, Share Food Program, Step Up To The Plate Campaign Student Meal Sites • All children and their caregivers are eligible. No ID is required. • Families can pick up one box per child with meals for the week. Site Name Address Days and Time Mon./Tues./Wed./Thurs./Fri. Mariana Bracetti Academy Charter School 1840 Torresdale Ave. 7 am – 1 pm Mastery Charter - Thomas Campus 927 Johnston St. Tues. & Fri. 12 pm – 2 pm Mastery Charter - Thomas Elementary 814 Bigler St. Tues. & Thurs. 1 pm – 4 pm D. Newlin Fell School 900 W Oregon Ave. Fri. 9 am – 2 pm Horace Furness High School 1900 S. 3rd St. Fri. 9 am – 2 pm Horatio B. Hackett School 2161 E. York St. Fri. 9 am – 2 pm John H. Webster School 3400 Frankford Ave. Fri. 9 am – 2 pm Jules E. Mastbaum High School 3116 Frankford Ave. Fri. 9 am – 2 pm 2051 E. Cumberland Fri. 9 am – 2 pm Kensington High School St. South Philadelphia High School 2101 S. Broad St. Fri. 9 am – 2 pm Senior Meal Sites • Residents age 60+ are eligible. No reservation needed. • Call senior center for meal schedule. Site Name Address Phone Number On Lok House Satellite 219 N. 10th St. 215-599-3016 Philadelphia Senior Center - Avenue of the Arts 509 S. Broad St. 215-546-5879 and Asia-Pacific Senior Resource Center South Philly Older Adult Center 1430 E. -

11 OSE Newsletter

THE MONTHLY SPECIAL 2018 Philadelphia Marathon, Photo by: Bill Foster Another amazing year of events in the book for the City of Philadelphia. As we’ve stated before, this is the fifth year in a row Philadelphia has been named an IFEA World Festival and Event City and 2018 has been proof, yet again, why that titles rings true for our City. We’ve hosted the Super Bowl Championship Parade, the 2018 Philadelphia International Festival of Arts, the 6th annual Jay-Z curated Made in America Music Festival and the 25th Anniversary of the Philadelphia Marathon, just to name a few. Check out our 2018 OSE Video for even more reason why Philly is on top! “The Present”, Photo by: Natalie Faragalli ● Deck the Alley at Elfreth's Alley (12/1) ● Hanukkah Celebration on Boathouse Row (12/3) ● Army-Navy Game at Lincoln Financial Field (12/8) ● SugarHouse New Year’s Event Fireworks on the Waterfront (12/31) 2018 Super Bowl Celebration, Photo by: Bill Foster 2018: A YEAR OF CELEBRATION The Office of Special Events At the end of each year, the Office of Special residents and visitors along our iconic Broad Events looks back and thinks, “How will we ever Street and Benjamin Franklin Parkway. top this?” How can we top the 2015 World Meeting of Families? How can we top the 2016 2018 quickly became a year of celebration for Democratic National Convention? How can we our City. On February 22nd the world top the 2017 NFL Draft? How can we top the renowned Reading Terminal Market 2018 Philadelphia Eagles Super Bowl celebrated its 125th Birthday. -

Board of Supervisors Meeting Agenda

801 Burrows Run Road Chadds Ford, PA 19317 BOARD OF SUPERVISORS MEETING AGENDA May 20, 2020 7:00 p.m. Remote Meeting via Zoom 1. Call to order 2. Township Recovery Update 3. Township Updates a. Chandler Mill Bridge b. State Street Bridge Repair and Detour c. Election Day 4. Executive Session announcement (Action Item) 5. Meeting Minutes (Action Item) th a. Consider Approval of the April 15 Meeting Minutes th b. Consider Approval of the May 6 Meeting Minutes 6. Old Business (Action Items for Ratification) 7. New Business (Action Items) a. Ratify the Delta Agreement for Grant Applications b. Proposed Resolution 2020-9 for SFG Grant Application c. Consider May 20, 2020 Bill Voucher in the amount of $591,017.06 d. Consider Biohabitats as the Township’s Greenway and Trails Engineer e. Consider Biohabitats Task Order #1 for the Magnolia Greenway Underpass f. Proposed Resolution 2020-10 Open Space Loan Deferral g. Consider Contract Addendum #1 for Vision Partnership Program Grant with increased cost of $5,568.00 for Contract Number 18334 (Zoning) h. Consider Contract Addendum #1 for Vision Planning Partnership Grant for Contract Number 18431 (TND Development) i. Escrow Release for Kennett Apartments j. Proposed Resolution 2020-11 to Extend Real Estate Tax Deadline 8. Public Comment 9. Motion to Adjourn TOWNSHIP REPRESENTATIVES Dr. Richard L. Leff, Chair Whitney S. Hoffman, Vice-Chair Scudder G. Stevens, Supervisor Eden R. Ratliff, Township Manager 801 Burrows Run Road Chadds Ford, PA 19317 (610) 388-1300 Fax (610) 388-0461 Website: www.kennett.pa.us Email: [email protected] Joining the Zoom public Board of Supervisors Meeting Wednesday, May 20, 2020 at 7:00 p.m. -

Philadelphia Resident Newsletter

Recipe of the Month: Fish Tacos • 1/2 teaspoon dried oregano • 1/2 teaspoon ground cumin • 1/2 teaspoon dried dill weed • 1 teaspoon ground cayenne pepper • 1 quart oil for frying1 pound cod fillets, cut into 2 to 3 ounce portions Newsletter for Columbus Property Management Residents July, 2018 • 1 (12 ounce) package corn tortillas • 1/2 medium head cabbage, finely shredded Table of Contents July is National Minority Mental Health Awareness Page 2: Directions Month 1. To make beer batter: In a large bowl, combine What to Do in Philly This June flour, cornstarch, baking powder, and salt. Mental health conditions do not Blend egg and beer or water, then quickly stir discriminate based on race, color, into the flour mixture (don’t worry about a few Page 3: Tips & Ideas gender or identity. Anyone can lumps). experience the challenges of 2. To make white sauce: In a medium bowl, mix Monthly Financial Tip: Borrow mental illness regardless of their together yogurt and mayonnaise. Slowly stir background. However, culture, race, in fresh lime juice until consistency is slightly Ingredients Fourth of July Safety Tips ethnicity and sexual orientation can runny. Season with jalapeno, capers, make access to mental health treatment much more difficult. • 1 cup all-purpose flour oregano, cumin, dill, and cayenne. • 2 tablespoons cornstarch 3. Heat oil in deep-fryer to 375 degrees F (190 • 1 teaspoon baking powder Page 4 America’s entire mental health system needs improvement, including when degrees C). it comes to serving marginalized communities. • 1/2 teaspoon salt 4. Dust fish pieces lightly with flour. -

Cities: Policing Strategies at Occupy Wall Street and Occupy Philadelphia

YODER FORMATTED.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 8/21/2012 5:50 PM A TALE OF TWO (OCCUPIED) CITIES: POLICING STRATEGIES AT OCCUPY WALL STREET AND OCCUPY PHILADELPHIA TRACI YODER* New York City - October 1, 2011 I’m standing on the walkway of the Brooklyn Bridge, peering down and trying to get a better glimpse of the scene unfolding beneath me. Hundreds of people are gathered below. From each direction, lines of police advance. “They’re going to mass arrest them,” shout many of the hundreds watching from above. Helplessly, we gaze down as our fellow demonstrators are cuffed and carried away. The mood on the walkway is tense. Assessing our situation, it becomes obvious that we too are trapped. The cables of the bridge suddenly look a lot like a cage. Figure 1: NYPD surround and mass arrest Occupy Wall Street protestors on the Brooklyn Bridge. Photo courtesy of Brennan Cavanaugh (Flickr Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License). Eventually, a friend and I start walking toward the Brooklyn side of the bridge. The crowd thins considerably, and it looks like we will be allowed to leave. We meet up with a hundred other people in a Brooklyn park—a mere fraction of the thousands that had set off from Zuccotti Park hours before. It starts to rain. As more people trickle into the park, an impromptu general assembly is called to decide on next steps. In the fifteen minutes I sit listening, police begin encircling the area. My friend and I head back to Zuccotti to regroup and gather word * Traci Yoder is currently the Student Organizer and Researcher/Writer for the National Lawyers Guild in NYC. -

COVID-19 RESOURCES Prepared by the Office of Senator Art Haywood

COVID-19 RESOURCES Prepared by the Office of Senator Art Haywood Updated May 11, 2020 NOTE: DUE TO EVOLVING CIRCUMSTANCES, ALL INFORMATION IN THIS DOCUMENT IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE. WE WILL ATTEMPT TO UPDATE THIS AS FREQUENTLY AS POSSIBLE. PLEASE NOTE THE DATE & TIME OF THE MOST RECENT UPDATE FOR EACH SUBHEADING. This document collects special provisions, service disruptions, and relief programs relating to the COVID-19 outbreak in Pennsylvania, with a special focus on the 4th Senate District. It has been updated by my staff on a regular basis to include the most accurate and up-to-date information. Table of Contents • COVID-19 Testing Sites – p. 2-8 • Food Resources – p. 8-20 • Special Provisions – State Agencies – p. 21 • Special Provisions – Utilities, Mortgages, Telecommunications – p. 43 • Special Provisions – 4th District (Philadelphia) – p. 45 • Special Provisions – 4th District (Montgomery County) – p. 54 If you would like to be receive an updated version of this document every week, please send an email to [email protected]. My office will continue to operate via phone and e-mail for the duration of the crisis. If you require individual assistance, please call (215) 242-8171 or e-mail [email protected]. Please also visit our self-service page for assistance here. Sincerely, Senator Art Haywood (4th District) Philadelphia & Montgomery Couunties 1 Prepared by the Office of Senator Haywood NOTE: DUE TO EVOLVING CIRCUMSTANCES, ALL INFORMATION IN THIS DOCUMENT IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE. WE WILL ATTEMPT TO UPDATE THIS AS FREQUENTLY AS POSSIBLE. PLEASE NOTE THE DATE & TIME OF THE MOST RECENT UPDATE FOR EACH SUBHEADING. -

May Natalie Edits

THE MONTHLY SPECIAL Nothing can compare to Philadelphia in May. There’s beautiful weather, all types of carnivals, races and street fairs to enjoy! We’re officially in our “high season” for events, with over 300 street festivals, parades and runs executed and permitted through our office to date. As more and more applications come through our office for processing, our staff continues to work around the clock to make sure your event needs are met and everything goes off without a hitch. The best part is getting out to the events to see all the hard work finally paid off. If you happen to spot us on site, be sure to say hello! We’re just as excited as you are for event day to be here! Photos via Visit Philly ● South Street Headhouse District Spring Festival on South Street (5/5) ● South of South Neighborhood Association Plazapalooza on Grays Ferry Triangle (5/12) ● Rittenhouse Row Spring Festival on Walnut Street (5/19) ● Kensington Kinetic Sculpture Derby and Arts Festival on Trenton Ave (5/19) ● South 9th Street Italian Market Festival on S. 9th St (5/19-20) Photo via SEPTA A SUSTAINABLE CHOICE! By: Olivia Gillison Construction in Philadelphia is booming, Therefore, might we suggest making a and Center City events are not going more sustainable choice for us all and anywhere, at least not anytime soon. If leave the car at home. One of the best anything, street festivals and athletic ways to limit traffic issues is to reduce the events are becoming more ubiquitous each number of vehicles on the roads, and year. -

IFEA Project

City of Philadelphia 2014 IFEA World Festival and Event City Award Presentation Prepared by the Office of the Managing Director - Office of Special Events TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction (i) Message from the Mayor (ii) Letter from the Managing Director (iii) Jazelle M. Jones - Deputy Managing Director/Director of Operations (iv) I. Community Overview (p. 1-11) II. Community Festivals and Events (p. 12-23) III. City/Governmental Support of Festivals and Events (p. 24-30) IV. Non-Governmental Community Support of Festivals and Events (p. 31-38) V. Leveraging “Community Capital” Created by Festivals and Events (p. 39-44) VI. Extra Credit (p. 45-48) VII. Addendum (p. 49-91) Photography Credits and Special Thanks (p. 92) Introduction Famous as the birthplace of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, Philadelphia offers much more than cobblestone streets and historical landmarks. Cultural, culinary, artistic and ethnic treasures abound in this city and its surrounding countryside. What makes Philadelphia so memorable is its unique blend of experiences that one must discover in person. By day, explore four centuries of history and architecture, beautiful neighborhoods, remarkable museum collections and endless shopping. After the sun sets, the city heats up with acclaimed performing arts, amazing dining and vibrant nightlife. All this and more attracts more than 39 million visitors to the Philadelphia region each year, sustaining 89,000 jobs in the hospitality sector and generating approximately $10 billion in annual economic activity. Philadelphia is a city on the rise and has become a world-class destination. i Message from the Mayor The City of Philadelphia, birthplace of the nation and home to world-class cultural institutions, universities and more than 1,100 hotel rooms, is unlike any other municipality in the United States. -

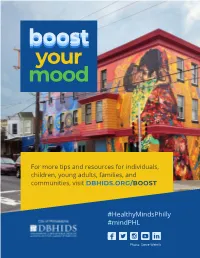

Your Boost Mood Boost

boost your mood For more tips and resources for individuals, children, young adults, families, and communities, visit DBHIDS.ORG/BOOST #HealthyMindsPhilly #mindPHL Photo: Steve Weinik Numbers to Know Places to Go boost your mood For more tips and resources for individuals, children, young adults, families, and communities, visit DBHIDS.ORG/BOOST For more tips and resources for individuals, children, young adults, families, and communities, visit DBHIDS.ORG/BOOST #HealthyMindsPhilly #mindPHL Photo: Steve Weinik The City of Philadelphia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services offers resources, services, and advocacy through a strong partnership with a network of healthcare providers to help people, whether they are uninsured or under-insured, lead a fulfilling life in a supportive community free of stigma. Phone Numbers Emergency Hotlines* Substance Use Treatment National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 800-273-8255 Community Behavioral Health* 888-545-2600 Veterans dial 1 Behavioral health services for Medicaid recipients Mental Health Crisis Line 215-685-6440 Behavioral Health Special Initiative (BHSI) 215-546-1200 Substance use services for those under and uninsured Child Protective Services 215-683-6100 Council on Compulsive Gambling 800-848-1880 Adult Protective Services 877-401-8835 Philadelphia Recovery Community Center 215-223-7700 Domestic Violence Hotline 866-723-3014 Supportive services in a community-based setting Homeless Outreach Hotline 215-232-1984 More Services Intellectual disAbility Services Mental Health First Aid Training 215-790-4996 Main office 215-685-5900 City Hall Connection, Philly311 311 Emergency line 215-829-5709 *Avaialble 24 hours a day, 7 days a week 24-Hour Services For immediate help, call 215-685-6440 or visit a crisis response center in your area: Friends Hospital Hall Mercer Children’s Crisis Response Center 4641 Roosevelt Blvd. -

A Kid's Guide To

PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS A Kid’s Guide To Philadelphia d’s guide PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS ki PROPERTY to OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS a If you’re looking for a snooze-cruise of a guidebook, this isn’t for you! A Kid’s Guide to Philadelphia wakes you up with fun and fact-filled PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS peeks at one of the most “spirited” cities in America, with a way-cool map and stickers inside! Philadelphia Written for kids of all ages, this book PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS reveals the secret stuff everyone wants to know: Who put a “Billy Penn Curse” on all Philly pro sports? What’s the “Whiz wit” secret when ordering a Philly cheesesteak? PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS Twin Lights Publishers Twin Lights Publishers, Inc. PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERSPhotography by Paul Scharff • Written PROPERTY by Ellen W. Leroe OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS d’s guide PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS ki to a PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS Philadelphia PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS Photography by Paul Scharff Written by Ellen W. Leroe PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS Copyright © 2011 by Twin Lights Publishers, Inc. -

Historic-District-Society-Hill.Pdf

SOCIETY HILL (and Pennsylvania Hospital of Washington Square West) HISTORIC DISTRICT Philadelphia Historical Commission 10 March 1999 Amended 13 October 1999 Amended 8 March 2019 1 ADDISON STREET - 400 Block Paving: concrete Curbs: concrete Sidewalks: concrete Light fixtures: none 425-35: See 424-34 Pine Street. *************** 400-10 See 401-09 Lombard Street. 412-34 See 411-49 Lombard Street. 2 ADDISON STREET - 500 Block Paving: granite block Curbs: aggregate concrete Sidewalks: brick Light fixtures: Franklin 501-15 "Addison Court" Eight, 4-story, 2-bay, red brick, contemporary houses. Recessed entrance with large sidelights; single-leaf 1-panel door; coupled casement sash 2nd and 3rd floors; concrete stringcourse 1st floor; brick soldiercourse 2nd and 3rd floors; recessed 4th floor hidden by brick parapet with cast stone coping; single-car garage door; end units turn into court. At each end, a brick and concrete arch spans Addison Street cartway. Built c. 1965 by Bower and Fradley, architects. Building permit. Contributing. 519 2-story, 3-bay, carriage house. Ground floor garage opening; hay loft door, two 8-light windows and metal pulley on 2nd floor. Built c. 1885. Contributing. 521-39 See 516-34 Pine Street. 541-43 See 536-40 Pine Street. *************** 500-14 "Addison Court" Eight, 4-story, 2-bay, red brick, contemporary houses. Recessed entrance with large sidelights; single-leaf 1-panel door; coupled casement sash 2nd and 3rd floors; concrete stringcourses 1st floor; brick soldiercourse 2nd and 3rd floors; recessed 4th floor hidden by brick parapet with cast stone coping; single-car garage door; end units turn into court. -

Ambassador Toolkit Welcome Aboard!

AMBASSADOR TOOLKIT WELCOME ABOARD! WWW.RIDEINDEGO.COM @RideIndego TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Indego Overview 1 Introduction . 2 A Who’s Who of Indego . 3. What is Indego? . 4. How Does Indego Work? . 4. How Do I Find a Station? . 7 Why Use Indego? . 9 Questions & Resources . 10 Community Involvement . 11 Section 2: Indego Ambassador Guide 12 Your Role as an Ambassador . 13 . Indego Ambassador Expectations and Responsibilities . 15. Indego Public Classes . 17. How to Organize an Indego Street Skills Class . 18 How to Organize an Indego Community Ride . 19 . Mini-grant Program to Fund Your Ideas for Promoting Indego . 21 Indego Street Skills . 22 SECTION 1 INDEGO OVERVIEW INTRODUCTION WELCOME, INDEGO AMBASSADORS! Indego is Philadelphia’s newest transportation system . The Indego bike share program provides exciting new opportunities for mobility, physical activity, recreation, and neighborhood connectedness . Indego and its partners are committed to linking Philadelphia residents with this new resource . That’s where you come in! In this toolkit you will find information about Indego programs, policies, and partners . You’ll also see tips for how to talk about bike share, help sell passes, and more . You are a key member of the Indego team and we are excited to work with you! AMBASSADOR TOOLKIT 2 A WHO’S WHO OF INDEGO The following partners are working together to spread the word about Indego: Indego is Philadelphia’s bike share system, owned by Bicycle Transit Systems is the Philadelphia-based the City of Philadelphia, operated by Bicycle Transit company that operates and maintains Indego’s stations Systems, sponsored by Independence Blue Cross .