Controlling Rodents in Commercial Poultry Facilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thirty-Something Reasons Why PHA Biodegradable Plastic Matters to Families

9/2/2015 Why Biodegradable Plastic PHA Matters to Families ... but Shouldn’t Thirty-Something Reasons Why PHA Biodegradable Plastic Matters to Families The Argument for Replacing Plastic with MHG’s NodaxTM PHA By Laura Mauney Do busy families care what plastic is made of any more than busy commuters care what kind of fuel goes into the vehicles that get people to work or school on time? Probably not. Most families probably care more about running smoothly from hour to hour, day to day, week to month to year. The question becomes, then, why should families care at all about the chemical composition of plastic? Image courtesy of Ekaterina_Minaeva / Shutterstock.com Take a quick look around the house. Look for plastic things. How many can you list? In less than five minutes, I came up with over 30 items: Broom and mop Egg carton Medicine bottles For families with Carryout bags Electronics and sealers children (mine are Cereal box liners casings Milk carton caps grown), add: Cleaning fluid Emergency Pet food bowls bottles water bottles Pet toys Baby Bottles Coffee maker Filtered water Pet treat bags Balls, blocks and Colander dispenser + Pet waste bags dolls Comb filters Sunglasses Diapers Cooking utensils Food storage Trash bags Lunch pails http://www.mhgbio.com/thirtyreasonsbiodegradableplasticmattersfamiliesshouldnt/ 1/7 9/2/2015 Why Biodegradable Plastic PHA Matters to Families ... but Shouldn’t Credit cards, bags Vacuum cleaner Pacifiers rewards cards, Food storage Wrapping for Shoes library card, containers bathroom tissue Rockers, riders license Juice bottles and paper and swings Dustpan Juice pitcher towels. -

Town of Fairfield Recycling Faqs

Item How to dispose Acids Hazardous waste To find the item you are looking for hold the Aerosol can (food grade only, empty) Put this item in your recycling bin. <Command> or <Ctrl> key + the letter "F" down together, type the item in the box in the Aerosol can (food grade only, (full or partially full) Put this item in your trash. upper right of your screen Aerosol can (NON food grade only, empty) Put this item in your trash. and press <Return> or <Enter>. NOTE: the first key noted is for Mac, the second key noted is Aerosol can (NON food grade only, (full or for PC. partially full) Take this to Hazardous waste Air Conditioner Put in Electronics trailer at the transfer station ( small fee) Aluminum baking tray Put in Recycling Bin - Clean it prior Aluminum foil Put in Recycling Bin - Clean it prior Aluminum Pie Plate Put in Recycling Bin - Clean it prior Ammunition Contact the Police department Animal waste and Bedding Put this item in your trash. Anti Freeze Bring to transfer station Consider donating to local school or creative reuse center. If they contain toxic Art Supplies materials, they should be brought to a Household Hazardous Waste collection event or facility. If not, place this item in the trash for disposal. Connecticut Department of Public Health recommends that a licensed asbestos Asbestos contractor abate the material. Put this item in your recycling bin., Loose caps go in the trash, remove and put any Aseptic Carton, such as a milk carton straws in the trash Ash - Coal Cool ash completely, Put in Bag in trash Ash - Charcoal Gripp Cool ash completely, Put in Bag in trash Ash - Manufactured logs and pellets Cool ash completely, Put in Bag in trash Consider starting a compost bin or food waste collection service ; otherwise put in Baked Goods Trash Balloon Put this item in your trash. -

Item Where to Dispose Acrylic Paint Transfer Station Aerosol Cans All-In-1

Item Where to Dispose Acrylic Paint Transfer Station Aerosol Cans All-in-1 Air Pillows Donate on Front Porch Forum Ammunition State Patrol Explosives Unit 802-244-8727 Antifreeze Appliances St. Johnsbury Transfer Station Arsenic (or pressure) treated wood St. Johnsbury Transfer Station - Construction and Demolition Asbestos VT Agency of Natural Resources Aseptic Containers Trash Ashes Garden, yard Asphalt St. Johnsbury Transfer Station - Construction and Demolition Automobiles Allards (802) 748-4452 Ballasts Aubuchon Hardware Batteries, Lead Acid trash Batteries, Alkaline trash Batteries, Rechargable trash Blender trash CD Cases Trash, or repurpose Cans, Tin All-in-1 Recycling Cardboard All-in-1 Recycling Carpet St. Johnsbury Transfer Station - Construction and Demolition Cat Litter Trash Catalogs All-in-1 Recycling, or repurpose for crafts Christmas Trees TBD Cleaning Products Clothing/Textiles donate at Salvation Army, Railroad Street, or H.O.P.E. Store, Lyndonville Concrete, Masonry St. Johnsbury Transfer Station - Construction and Demolition Construction and Demolition St. Johnsbury Transfer Station - Construction and Demolition Copier Toner See manufacturer instructions, in most cases they provide return mail service when you purchase a new one. Couch - ruined St. Johnsbury Transfer Station - $54.00 DVD, CDs Trash Egg Carton, Cardboard All-in-1 Recycling, or save for local egg farmers Egg Carton, Plastic All-in-1 Recycling, or save for local egg farmers, or use to start seeds Egg Carton, Styrofoam Trash Electronics This category includes computers, all computer peripherals, and TVs. These materials are banned from the landfill, but they can be recycled for Fire Extinguishers Reed Supply, Mill St., St. Johnsbury Fireworks, Explosives Unwanted ammunition, road flares, and fireworks must be handled properly. -

Packaging Technology

PACKAGING TECHNOLOGY KAZAKH NATIONAL AGRARIAN UNIVERSITY ALMATY, KAZAKHSTAN 19 - 30 OCT. 2015 by ROSNITA A. TALIB BSc (Food Sc & Tech), MSc. (Packaging Engineering) UPM PhD (Materials Engineering) Sheffield, UK. Department of Process and Food Engineering Faculty of Engineering 43400 UPM Serdang, Selangor Universiti Putra Malaysia Email: [email protected] Course Outcomes Students are able to : 1. To describe the functions, basic packaging design elements and concepts 2. To analyse various types of packaging materials for use on appropriate food 3. To differentiate standard test methods for packaging quality control 4. Describe various types of packaging equipment in food industry References/Textbooks 1. Soroka, W. (2009) Fundamentals of Packaging Technology. Naperville. Instituue of Packaging Professionals. 2. Klimchuk, M.R. and Krasovec, S.A. (2006) Packaging Design Successful Product Branding from Concept to Shelf. Hoboken. John Wileys & Sons 3. Morris, S.A. (2010). Food Packaging Engineering. Iowa: Blackwell Publishing Professional. 4. Robertson, G.L. (2006). Food Packaging - Principles and Practice (2nd Edition). Boca Raton: CRC Press. 5. Kelsey, R.J. (2004). Handbook of Package Engineering (4th Edition). Boca Raton: CRC Press. Package vs Packaging - Simple examples of package: boxes on the grocer's shelf and wrapper on a candy bar. - The crate around a machine or a bulk container for chemicals. - Generically, package is any containment form. - Package (noun) is an object. A physical form that is intended to contain, protect/preserve; aid in safe, efficient transport and distribution; and finally act to inform and motivate a purchase decision on the part of a consumer. Package vs Packaging Packaging is Packaging also - Packaging is a verb, reflecting the ever-changing nature of the The development and production of medium. -

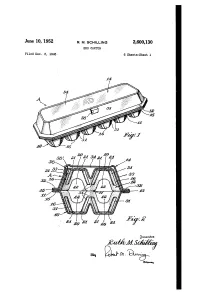

EGG CARTON Filed Dec

June 10, 1952 R. M. SCHILLING 2,600,130 EGG CARTON Filed Dec. 3, 1945. 6 Sheets-Sheet 1 June 10, 1952 R. M. SCHILLING 2,600,130 EGG CARTON Filed Dec. 3, 1945 6 Sheets-Sheet 2 June 10, 1952 R. M. scHILLING 2,600,130 EGG CARTON Filed Dec. 3, 1945 6 Sheets-Sheet 3 aese essessease VAWA) All ly/AWA WAITWA/WAIVIM/WATWIAI (AAA-AA-AA-AA C - seese Neerae YawawasaNANAAAAAALI sSSSSSS27 As Area - June 10, 1952 R. M. SCHILLING 2,600,130 EGG CARTON Filed Dec. 3, 1945 6 Sheets-Sheet 4 a 4642 50464,2346 042 42 4620 37 June 10, 1952 R. M. SCHILLING 2,600,130 EGG CARTON Filed Dec. 3, 1945 6 Sheets-Sheet 5 20 63 67 63 69 67 62 (seeAll 4 INA Y 69E9E9E9E9E9ESISDEES's Se21 Eas EastEs 62 22769393 21 N *2\Stats: NS4 (S.395 S. 60 62 62. 69.64 72 3: 6 22 7a 64.7065777a TT66 Zze 67, Sebsite&ressbváxissilsEA 2. NS 55 626Z 241.3 Sa:É, ASL June 10, 1952 R. M. SCHILLING 2,600,130 EGG CARTON Filed Dec. 3, 1945 6 Sheets-Sheet 6 s. 24.) be Patented June 10, 1952 2,600,130 UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE 2,600,130 EGG CARTON Ruth M. Schilling, St. Paul, Minn., assignor, by mesne assignments, to Shellmar Products Cor poration, Chicago, Ill., a corporation of Dela Ware Application December 3, 1945, Serial No. 632,331 8 Claims. (C. 229-2.5) 2 My invention relates to an improvement in by my carton from movement in any direction. -

Iceland UK to Go Plastic-Free by 2023 Concerned Consumers Say No to Plastic Packaging Studies Reveal Consumer Preferences Loué

PACK & PERFORM Hartmann Newsletter 1/2019 Think You don’t need to be an egghead to think News outside the box. Concerned consumers say no to plastic packaging How are food producers and retailers responding to the global outcry against plastic islands? Page 2 This issue Studies reveal Iceland UK to go Loué celebrates consumer plastic-free by turning 60 with preferences 2023 a contest GfK studies of egg consumers in Major UK food retail chain climbs Unique labels drive French egg Europe and the US reveal advantages consumer ratings with pledge to ban producer’s 60th anniversary of saying no to plastic in the egg plastic packaging. Page 6 promotion – and help sell more category. Page 5 eggs. Page 7 Hartmann | Think News | 1/2019 Thoughts from the editor Ute Scamperle European Customer Marketing Manager Plastic islands and how consumers, not us, are driving a ‘domino effect’ In this issue of Think News we ask what we can do as egg producers, retailers and consumers to reduce the terrible environmental effects of plastic waste. In particular, we tell the story of how Iceland in the UK became one of the Wave goodbye first retailers to reduce single-use plastic packaging, propelling them to the top of the consumer-rating charts. to single-use And we show you the ‘domino effect’ as retailers around the world make their own moves away from plastic. plastic packaging We also look at findings from consumer How we get to eat our So that is how we get to eat our own studies in Europe and the United States own plastic trash plastic trash along with toxins such as which suggest switching from plastic to Plastic is great for protecting food phthalates and bisphenol A. -

Why Can't These Be Recycled in My Curbside Program?

Why can’t these be recycled in my curbside program? Gift wrap - This type of paper is not recyclable because it is often printed with too much colored ink, foil, glitter, flocking or other non-recyclable items. These materials are contaminants and need to be removed in the paper pulping process. Recycling 101 Pizza boxes and soiled paper - Grease, paint, plastic and or oil on food boxes or paper will show up further down the paper making process causing a defect. These spots will not print or glue properly or may cause the paper to be stained. When these non-paper materials become part of the new paper, the new paper is rejected and will end up in the garbage. Paper and Rigid Container Recycling Information for Curbside Recycling Poly-coated paper packaging for the refrigerator or freezer - These items are not recyclable because they have a plastic coating, which does not break down at the Place items in your cart loose or in paper bags. same rate as non-coated paper. Poly-coated papers are often removed in the paper-making process as waste. Please recycle Do not recycle Egg cartons - Egg cartons have been manufactured using recycled paper. Egg carton Paper Art work with paint and non-paper fibers are so short, they are not suitable for making new paper products. items Window and ceramic glass - Recyclable glass must meet quality standards to Boxes from the refrigerator or freezer ensure it can be marketed and made into new glass containers. Contaminants such Poly-coated boxes (ex. butter, cream as ceramics, other types of glass, metal rings and caps cause problems in the cheese, frozen dinner boxes) recycling process and must be kept out of recyclable glass. -

Numerical Methods in Soil Hydrology: TDR Waveform Analysis and Water Vapor Diode Simulation Zhuangji Wang Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2017 Numerical methods in soil hydrology: TDR waveform analysis and water vapor diode simulation Zhuangji Wang Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Soil Science Commons Recommended Citation Wang, Zhuangji, "Numerical methods in soil hydrology: TDR waveform analysis and water vapor diode simulation" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 15636. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/15636 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Numerical methods in soil hydrology: TDR waveform analysis and water vapor diode simulation by Zhuangji Wang A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Soil Science (Soil Physics) Program of Study Committee: Robert Horton, Major Professor Daniel Attinger Dan B. Jaynes James Rossmanith Tom Sauer Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2017 Copyright © Zhuangji Wang, 2017. All rights reserved. ii DEDICATION For My parents, Zhaokuan Wang and Yuye Hu iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ......................................................................................................................... -

Increase Production Efficiency and Eliminate Errors with Advanced Egg Carton Coding Solutions

Whitepaper Series Increase Production Efficiency and Eliminate Errors with Advanced Egg Carton Coding Solutions ©2012 Videojet Technologies Inc. Page 1 Whitepaper Series INCREASE PRODUCTION EFFICIENCY AND ELIMINATE ERRORS WIH ADVANCED EGG CARTON CODING SOLUTIONS Egg carton coding is the most common way that eggs are tracked for traceability. It’s also the most common way consumers determine the quality of the eggs they are about to buy, and most importantly, it is how they determine the quality of their eggs once they have them at home. However, the sell by or best by information on the egg carton is often poorly printed, even on higher-priced specialty eggs. Since this information is the key traceability link, it is vital that this is printed clearly. Newer Continuous Ink Jet (CIJ) and Laser marking technology not only offers better print quality, but is also easier to setup and changeover, and requires less maintenance than current printing solutions. Why code on egg cartons? Carton level identification is mandated in the United States by the USDA (7 CFR 56), in Canada by the CFIA (C.R.C. 284), in Europe by EC Regulation 557/2007 and comparable organizations in other countries. It provides traceability information that links the eggs within the carton back to the farm and date of packing. With this information, government authorities can alert the public and manage a recall of questionable eggs. This identification is currently the first location the consumer finds the date and lot coding information for eggs If reliably getting the right traceability code on the right carton isn’t hard enough, the increasing variety of egg carton styles, sizes and materials adds to the challenge. -

The Upgrade for Your Egg Marking and Coding

Marking and coding eggsEP The UPgrade for your egg marking and coding Integration partners 100% protection SEALTRONIC trouble-free startup, every time Industrial Inkjet Printer Marking and coding eggsEP JET3up EP – the integrated solution for marking and coding eggs and egg cartons The JET3up EP is a special industrial printer for marking and coding eggs and egg packages. It is compatible with egg sorting and packaging machines from the leading manufacturer (Moba Group). The cooperation between LEIBINGER and the Moba Group makes it possible to conveniently integrate the continuous inkjet printer into their egg sorting machines. That simplifies the process of marking and coding eggs and egg cartons many times over. The benefit to you from the JET3up EP complete integration 1. Automatic print data transfer from the egg sorting machine to the printer 2. Accurate imprinting of eggs using egg-specific data 3. Positionally accurate printing on the egg shell/carton 4. Central management/modification of the print data 5. Variable data updated automatically (such as “best by” dates) 6. Convenient changing of the marking and coding imprint Continuous inkjet printers (CIJ) in the egg industry LEIBINGER CIJ printers label every possible product, material and surface without making contact, using fixed and variable data while production is in progress. Why use CIJ technology to mark and code egg shells and egg cartons? The continuous inkjet printer printhead can be flexibly installed in all directions and thereby enables full flexibility for positioning the mark/code. Thanks to the non-contact printing, different sized eggs can be marked/coded without readjusting the printhead. -

Sustainable Plastic Packaging

® Thermoforming ® Quarterly A JOURNAL OF THE THERMOFORMING DIVISION OF THE SOCIETY OF PLASTIC ENGINEERS FIRST QUARTER 2013 I VOLUME 32 I NUMBER 1 MANAGE WHAT YOU MEASURE Revisiting Labor-Based Costing pages 8-11 INSIDE … Sustainability: Strengthening the Message pages 20-25 SPE Council Review pages 28-29 WWW.THERMOFORMINGDIVISION.COM Thermoforming FIRST QUARTER 2013 Thermoforming Quarterly® VOLUME 32 I NUMBER 1 Quarterly® A JOURNAL PUBLISHED EACH Contents MANAGE WHAT YOU MEASURE CALENDAR QUARTER BY THE THERMOFORMING DIVISION I Departments OF THE SOCIETY OF Chairman’s Corner R 2 PLASTICS ENGINEERS Thermoforming in the News R 4 Editor Front Cover Conor Carlin University News R 15 (617) 771-3321 Thermoforming & Sustainability R 20-25 [email protected] Sponsorships Laura Pichon (847) 829-8124 +LJKHUSULFHG *URZLQJ DQGRU'HSOHWHG 'HPDQGIRU )RVVLO)XHOV 3ODVWLFV :RUOGZLGH Fax (815) 678-4248 [email protected] 3ODVWLFV 6XVWDLQDELOLW\ (IIRUWV I Features Conference Coordinator &RQVXPHUDQG 5HJXODWRU\ 5HWDLOHU 3UHVVXUHV Lesley Kyle 3UHVVXUHV *+*V HPLVVLRQVHWF The Business of Thermoforming R 8-11 (914) 671-9524 Page 20 The Dangers of Direct Labor-Based Costing in Manufacturing [email protected] Thermoforming Division Industry Practice R 12-13 Executive Assistant Grant to Help Students See Manufacturing as Opportunity Gwen Mathis Cover Artwork courtesy of Dallager Photography (706) 235-9298 All Rights Reserved 2012 Fax (706) 295-4276 [email protected] Thermoforming Quarterly® is pub- lished four times annually as an infor- mational and educational bulletin to Page 12 the members of the Society of Plastics Engineers, Thermoforming Division, and the thermoforming industry. The name, “Thermoforming Quarterly®” and its logotype, are registered trademarks of the Thermoforming Division of the Society I In This Issue of Plastics Engineers, Inc. -

Egg Submission and Testing Guidelines

Egg Submission and Testing Guidelines . Fire Contaminant Testing Due to increase in urban wildfire, there is concern about backyard chickens ingesting contaminants from the ground and transmitting these to their eggs. Various heavy metals (including lead) are found in old paint (before 1978), old plumbing (before 1986), electronics, batteries (including old lead-acid car batteries) and many other things found around the home. Thus we recommend testing eggs for heavy metals (especially lead) so that you can make an informed decision about the safety of your eggs. For guidance, the FDA recommends that children do not consume more than three micrograms of lead per day. Instructions for submitting eggs Packaging eggs: 1. Ship 2-6 eggs (6 eggs max) from your flock. 2. Wrap eggs in tissue to individually cushion eggs, then place eggs inside an egg carton. 3. Wrap the carton with bubble wrap and/or ship in a box with crumpled paper, shredded paper, or packing peanuts. 4. Include this form <see requested egg study info.docx or request egg study info – spanish.docx> or a sheet with the information requested in the section below 5. Seal box securely with tape Click here for free shipping supplies. Please include the following information with your shipment: ● Address where hens reside (Street name, City, Zip -- we do not need the number of the address) ● County where the hens reside ● Number of hens in flock ● Date eggs were collected ● Length of time you have owned the chickens ● Age of chickens ● Year the coop the chickens live in was built ● Year your house was built (Note: our goal with this information is to determine if the chickens may have any contamination from lead paint used before 1978) Ship eggs to: <Insert the lab address here> If you live in or near <insert your county/region here>, you may also choose to drop your eggs off in person directly to <insert local contact info if you want this option> If you would like assistance with shipping costs, please contact <insert contact info if your budget includes support for shipping samples>.