Grayson M Draft 6Apr21rbmcommentsupto36.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title Author Gr Elementary Approved Literature List by Grade

Elementary Approved Literature List by Grade Title Author Gr Alison’s Wings, 1996 Bauer, Marion Dane K All About Seeds Kuchalla, Susan K Alpha Kids Series Sundance Publishers K Amphibians Are Animals Holloway, Judith K An Extraordinary Egg Lionni, Leo K Animal Strike at the Zoo Wilson, Karma K Animals Carle, Eric K Animals At Night Peters, Ralph K Anno's Journey (BOE approved Nov 2015) Anno, Mitsumasa K Ant and the Grasshopper, The: An Aesop's Fable Paxton, Tom K (BOE approved Nov 2015) Autumn Leaves are Falling Fleming, Maria K Baby Animals Kuchalla, Susan K Baby Whales Drink Milk Esbensen, Barbara Juster K Bad Case of Stripes, A Shannon, David K Barn Cat Saul, Carol P. K Bear and the Fly, The Winter, Paula K Bear Ate Your Sandwich, The (BOE Approved Apr 2016) Sarcone-Roach, Julia K Bear Shadow Asch, Frank K Bear’s Busy Year, 1990 Leonard, Marcia K Bear’s New Friend Wilson, Karma K Bears Kuchalla, Susan K Bedtime For Frances Hoban, Russell K Berenstain Bear’s New Pup, The Berenstain, Stan K Big Red Apple Johnston, Tony K updated April 15, 2016 *previously approved at higher grade level 1 Elementary Approved Literature List by Grade Title Author Gr Big Shark’s Lost Tooth Metzger, Steve K Big Snow, The Hader, Berta K Bird Watch Jennings, Terry K Birds Kuchalla, Susan K Birds Nests Curran, Eileen K Boom Town, 1998 Levitin, Sonia K Buildings Chessen, Betsy K Button Soup Disney, Walt K Buzz Said the Bee Lewison, Wendy K Case of the Two Masked Robbers, The Hoban, Lillian K Celebrating Martin Luther King Jr. -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films Through Grotesque Aesthetics

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-10-2015 12:00 AM Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics Leah Persaud The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Angela Borchert The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Leah Persaud 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Persaud, Leah, "Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3244. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3244 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO’S THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL? DEFINING AND SUBVERTING THE FEMALE BEAUTY IDEAL IN FAIRY TALE NARRATIVES AND FILMS THROUGH GROTESQUE AESTHETICS (Thesis format: Monograph) by Leah Persaud Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Leah Persaud 2015 Abstract This thesis seeks to explore the ways in which women and beauty are depicted in the fairy tales of Giambattista Basile, the Grimm Brothers, and 21st century fairy tale films. -

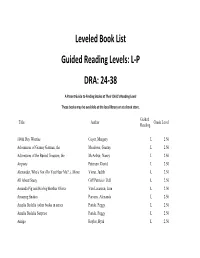

Leveled Book List Guided Reading Levels: L-P DRA: 24-38

Leveled Book List Guided Reading Levels: L‐P DRA: 24‐38 A Parent Guide to Finding Books at Their Child’s Reading Level These books may be available at the local library or at a book store. Guided Title Author Grade Level Reading 100th Day Worries Cuyer, Margery L 2.50 Adventures of Granny Gatman, the Meadows, Granny L 2.50 Adventures of the Buried Treasure, the McArthur, Nancy L 2.50 Airports Petersen, David L 2.50 Alexander, Who's Not (Do You Hear Me?..)..Move Viorst, Judith L 2.50 All About Stacy Giff Patricia / Dell L 2.50 Amanda Pig and Her big Brother Oliver Van Leeuwen, Jean L 2.50 Amazing Snakes Parsons, Alexanda L 2.50 Amelia Bedelia (other books in series Parish, Peggy L 2.50 Amelia Bedelia Surprise Parish, Peggy L 2.50 Amigo Baylor, Byrd L 2.50 Anansi the Spider McDermott, Gerald L 2.50 Animal Tracks Dorros, Arthur L 2.50 Annabel the Actress Starring in Gorilla My Dream Conford, Ellen L 2.50 Anna's Garden Songs Steele, Mary Q. L 2.50 Annie and the Old One Miles, Miska L 2.50 Annie Bananie Mover to Barry Avenue Komaiko, Leah L 2.50 Arthur Meets the President Brown, Marc L 2.50 Artic Son George, Jean Craighead L 2.50 Bad Luck Penny, the O'Connor Jane L 2.50 Bad, Bad Bunnies Delton, Judy L 2.50 Beans on the Roof Byare, Betsy L 2.50 Bear's Dream Slingsby, Janet L 2.50 Ben's Trumpet Isadora, Rachel L 2.50 B-E-S-T Friends Giff Patricia / Dell L 2.50 Best Loved doll, the Caudill, Rebecca L 2.50 Best Older Sister, the Choi, Sook Nyul L 2.50 Best Worst Day, the Graves, Bonnie L 2.50 Big Al Yoshi, Andrew L 2.50 Big Box of Memories Delton, -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Nosferatu. Revista De Cine (Donostia Kultura)

Nosferatu. Revista de cine (Donostia Kultura) Título: La ciencia-ficción en el cine de Jack ArnoId. El espacio ambiguo de la monstruosidad Autor/es: Heredero, Carlos F. Citar como: Heredero, CF. (1994). La ciencia-ficción en el cine de Jack ArnoId. El espacio ambiguo de la monstruosidad. Nosferatu. Revista de cine. (14):100-115. Documento descargado de: http://hdl.handle.net/10251/40894 Copyright: Reserva de todos los derechos (NO CC) La digitalización de este artículo se enmarca dentro del proyecto "Estudio y análisis para el desarrollo de una red de conocimiento sobre estudios fílmicos a través de plataformas web 2.0", financiado por el Plan Nacional de I+D+i del Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad del Gobierno de España (código HAR2010-18648), con el apoyo de Biblioteca y Documentación Científica y del Área de Sistemas de Información y Comunicaciones (ASIC) del Vicerrectorado de las Tecnologías de la Información y de las Comunicaciones de la Universitat Politècnica de València. Entidades colaboradoras: Revenge of the Creature (1 955), de Jack Arnold La ciencia-ficción en el cine de JackArnold El espacio ambiguo de la monstruosidad Carlos E Heredero asta comienzos de los rar en su actividad. Tampoco amanuense contratado ocasio años setenta, la figura y la desde las páginas antagonistas nalmente por diferentes estudios Hfilmografia de un cineas de Positif, y ni siquiera desde la de un Hollywood en crisis. ta llamado Jack Amold habían perspectiva militante de Ber pasado completamente desaper trand Tavemier (un apasionado Será necesario esperar, por tan cibidos para los ojos de la crítica "apóstol de la serie B", con el ol to, a las llamadas de atención del y de la historiografía. -

JACK ARNOLD Di Renato Venturelli

JACK ARNOLD di Renato Venturelli Tra gli autori della fantascienza anni ‘50, che rinnovò la tradizione del cinema fantastico e dell’horror, il nome che si impone con più evidenza è quello di Jack Amold. Il motivo di questo rilievo non sta tanto nell’ aver diretto i capolavori assoluti del decennio (La cosa è di Hawks, L’invasione degli ultracorpi è di Siegel...), quanto nell’aver realizzato un corpus di film compatto per stile e notevole nel suo insieme per quantità e qualità. Gli otto film fantastici realizzati fra il 1953 e il 1959 testimoniano cioè un autore riconoscibile, oltre a scandire tappe fondamentali per la mitologia del cinema fantastico, dalla Creatura della Laguna Nera (unico esempio degli anni ‘50 ad essere entrato nel pantheon dei mostri classici) alla gigantesca tarantola, dalla metafora esistenziale di Radiazioni B/X agli scenari desertici in cui l’uomo si trova improvvisamente di fronte ai limiti delle proprie conoscenze razionali. Uno dei motivi di compattezza del lavoro di Amold sta nella notevole autonomia con cui poté lavorare. Il suo primo film di fantascienza, Destinazione… Terra (1953), segnava infatti il primo tentativo in questa direzione (e nelle tre dimensioni) da parte della Universal-International. Il successo che ottenne, e che assieme agli incassi del Mostro della laguna nera risollevò la compagnia da una difficile situazione economica, fu tale da permettere ad Arnold di ritagliarsi una zona di relativa autonomia all’interno dello studio: “Nessuno a quell’epoca era un esperto nel fare film di fantascienza, così io pretesi di esserlo. Non lo ero, naturalmente, ma lo studio non lo sapeva, e così non si misero mai a discutere, qualsiasi cosa facessi”. -

Monster of the Week Monster of the Week

Monster of the Week Monster of The Week By Michael Sands Illustrated by Daniel Gorringe Edited by Steve Hickey First edition, June 2012. ISBN (print edition): 978-0-473-20466-2 ISBN (PDF edition): 978-0-473-20467-9 For Amanda and Zelda with love, for their support and tolerance over the very long time this game was in development. Acknowledgements Thanks go to many people who helped me with this game. Firstly, to Vincent Baker for Apocalypse World, and for not minding that I took his rules and changed them all around to fit my vision. Also, to the many playtesters who indulged me by joining in and hunting monsters over four or five years of development (especially my regular Monday night crew: Scott Kelly, Bruce Norris, Andrew McLeod, Jason Pollock, and Stefan Tyler). Steve Hickey, who edited the game, was one of my first enthusiastic fans, the first Keeper (aside from me), and has provided great feedback throughout the process. Thanks to my other early fans: Jenni Dowsett, Sophie Melchior, Hamish Cameron, and Stefan Tyler. Daniel Gorringe for the art: he was on the same page as me instantly in terms of style, and his work is fantastic. Thanks to Amanda Reilly, Todd Furler, Patrice Hede, Stephanie Pegg, and Peter Aronson for finding typos above and beyond the call of duty. Thanks also to everyone who contributed to the game's fundraising campaign: the game would have been much rougher without you. And, finally, to my wife and daughter. As the dedication says, they put up with a lot while I was writing, and were supportive all along. -

Jack Arnold: La Firma Di Un Artista

www.clubcity.info CITYcircolo d’immaginazione Jack Arnold: la firma di un artista RETROSPETTIVA CITYcircolo d’immaginazione retrospettiva Jack Arnold: la firma di un artista di Roberto Milan da “Interventi” (supplemento a City) a cura del club City Circolo d’Immaginazione, 1983, n°4. Studio grafico e impaginazione by Giorgio Ginelli, 2010. e impaginazione Studio grafico La tecnica cinematografica si è molto raffinata in questi ultimi anni, 1 Robert Wise (1914-2005) è stato uno permettendo effetti speciali e soluzioni sceniche un tempo impen- dei più importanti registi statunitensi, sabili. Il genere più interessato a questo fenomeno è stato, indub- premiato con vari Oscar. Nel campo del biamente, quello fantascientifico che, grazie all’operato di registi cinema fantastico occorre ricordare: come Stanley Kubrick, Steven Spielberg, John Boorman e John “Andromeda”, 1971; “Audrey Rose”, 1977; “Gli invasati”, 1963. Carpenter (per citare alcuni fra gli esempi più attuali) ha assunto Don Siegel (1912-1991) iniziò la carriera un ruolo di avanguardia. Alla base di quest’evoluzione stanno però come regista di cortometraggi che ven- quei registi che, nel periodo compreso fra gli anni Cinquanta e nero premiati con l’Oscar. Molte le regie Sessanta, hanno contribuito con le loro opere al diffondersi delle effettuate (tra cui “Ispettore Callaghan tematiche fantascientifiche nel genere cinematografico. il caso Scorpio è tuo“con Clint Eastwo- Fra i vari Robert Wise, Don Siegel, Val Guest, Richard Fleischer1 od). “L’invasione degli ultracorpi” è il ben si inserisce Jack Arnold, la cui opera si articola in un arco co- suo unico vero grande film di successo stituito da numerose pellicole (ben otto), alcune delle quali con- in campo fantascientifico. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Current Cinema

Touch Each Picture to Read the Story INK TALES Star Wars: Captain Phasma The brilliant Kelly Thompson brings Issue 30 Cover: the famed First Order leader to life Illustration by in a Marvel miniseries that leads up Michael Koelsch to the events of The Last Jedi. By Danny Munso Letter from the Publisher BLOODLIST TALES Contributors Killing Time Jose Prendes combines horror, comedy Masthead and time travel into a script that landed him on the 2017 compendium Art and of the best dark scripts in Hollywood. Photo Credits By Danny Munso RETRO Reservoir Dogs: 25th-Anniversary Q&A Writer-director Quentin Tarantino, actor Michael Madsen and producer Lawrence Bender reminisce about the iconic heist flick, which emerged from a Sundance filmmakers lab. By Jeremy Smith q TV DVR’D Drunk History Derek Waters talks about the progression and process behind his hit Comedy Central series. By Danny Munso TV STREAMED Godless Writer-director Scott Frank on wrangling his beloved film script into an epic Netflix miniseries. By Jeremy Smith TV STREAMED The Punisher Steve Lightfoot on capturing the returning-vet experience and writing the tortured character at the heart of Netflix’s latest Marvel series. By Danny Munso INSIDE THE ACADEMY’S 2017 NICHOLL COMPETITION Goodfellows Meet this year’s Nicholl Fellowship recipients, rewarded for writing their labors of love by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. By Claude Chung q COVER STORY Star Wars: The Last Jedi The Writer/Director Rian Johnson discusses his film’s biggest moments and what it took to fly the space opera saga into uncharted territory. -

90Th Annual Academy Awards® Oscar® Nominations Fact Sheet

90TH ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS® OSCAR® NOMINATIONS FACT SHEET Best Motion Picture of the Year: Call Me by Your Name (Sony Pictures Classics) - Peter Spears, Luca Guadagnino, Emilie Georges and Marco Morabito, producers - This is the first nomination for all four. Darkest Hour (Focus Features) - Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Lisa Bruce, Anthony McCarten and Douglas Urbanski, producers - This is the fifth nomination for Tim Bevan. His previous Best Picture nominations were for Elizabeth (1998), Atonement (2007), Les Misérables (2012) and The Theory of Everything (2014). This is the sixth nomination for Eric Fellner. His previous Best Picture nominations were for Elizabeth (1998), Atonement (2007), Frost/Nixon (2008), Les Misérables (2012) and The Theory of Everything (2014). This is the second Best Picture nomination for both Lisa Bruce and Anthony McCarten, who were previously nominated for The Theory of Everything (2014). This is the first nomination for Douglas Urbanski. Dunkirk (Warner Bros.) - Emma Thomas and Christopher Nolan, producers - This is the second Best Picture nomination for both. They were previously nominated for Inception (2010). Get Out (Universal) - Sean McKittrick, Jason Blum, Edward H. Hamm Jr. and Jordan Peele, producers - This is the second Best Picture nomination for Jason Blum, who was previously nominated for Whiplash (2014). This is the first Best Picture nomination for Sean McKittrick, Edward H. Hamm Jr. and Jordan Peele. Lady Bird (A24) - Scott Rudin, Eli Bush and Evelyn O'Neill, producers - This is the ninth nomination for Scott Rudin, who won for No Country for Old Men (2007). His other Best Picture nominations were for The Hours (2002), The Social Network (2010), True Grit (2010), Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2011), Captain Phillips (2013), The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) and Fences (2016).