Evaluation of Community Resilience in Teso, Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uganda Floods – 2 October 2007

SITUATION REPORT Nº 5 – UGANDA FLOODS – 2 OCTOBER 2007 HIGHLIGHTS FLOODS SPREAD TO ADDITIONAL DISTRICTS IN CENTRAL UGANDA BLOODY DIARRHOEA IN KATAKWI DISTRICT INCREASES CONCERN OVER HEALTH AND WATER AND SANITATION SITUATION IN FLOOD-AFFECTED AREAS The information contained in this report has been gathered by the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) from sources including the Government of Uganda, UN agencies, non-governmental organizations and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). 4. On 19 September, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni declared a state of emergency in the areas flood-affected areas of Eastern Uganda, which was endorsed by Parliament on 25 September. 5. Planning for the humanitarian response to the disaster is based on some 50,000 households, or approximately 300,000 people, being affected by the rainfall and associated flooding. This planning figure may be expected to change as additional assessments come in and/or depending on whether the intensified rainfall continues. 6. The Uganda Department of Meteorology, in its seasonal rainfall forecast for September to December, predicts high chances for normal to above normal rains to continue over most parts of the eastern region of Uganda. 7. The flooding has had a severe impact on water and sanitation in the affected areas, which damage increases the risk of outbreak of waterborne diseases such as cholera as the floodwaters recede. Concerns have been elevated in recent days as reports of Situation Overview several cases of bloody diarrhoea have been received from Katakwi district. Cholera response contingency planning is being conducted in regional 1. -

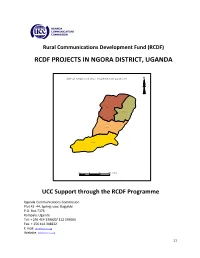

Rcdf Projects in Ngora District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN NGORA DISTRICT, UGANDA MA P O F N G O R A D IS T R IC T S H O W IN G S U B C O U N TIE S N Kap ir M ukur a Ngor a Kob w in 20 0 20 40 Km s UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 11 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....….…3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……..….…4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….……….…..4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Ngora district……………….……….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Ngora district………..………………….……………...…….14 10- Map of Ngora district showing sub counties………..……………………..……….15 11- Table showing the population of Ngora district by sub counties……..…...15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Ngora district…………………………………….……..….…16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 12 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development. It is therefore vital that ICTs are made accessible to all people so as to make those people have an opportunity to contribute and benefit from the socio-economic development that ICTs create. -

Bukedea District

National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles Bukedea District April 2017 National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles – Bukedea District This report presents findings of National Population and Housing Census (NPHC) 2014 undertaken by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). Additional information about the Census may be obtained from the UBOS Head Office, Statistics House. Plot 9 Colville Street, P. O. Box 7186, Kampala, Uganda; Telephone: +256-414 706000 Fax: +256-414 237553; E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.ubos.org Cover Photos: Uganda Bureau of Statistics Recommended Citation Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2017, The National Population and Housing Census 2014 – Area Specific Profile Series, Kampala, Uganda National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles – Bukedea District FOREWORD Demographic and socio-economic data are useful for planning and evidence-based decision making in any country. Such data are collected through Population Censuses, Demographic and Socio-economic Surveys, Civil Registration Systems and other Administrative sources. In Uganda, however, the Population and Housing Census remains the main source of demographic data, especially at the sub-national level. Population Census taking in Uganda dates back to 1911 and since then the country has undertaken five such Censuses. The most recent, the National Population and Housing Census 2014, was undertaken under the theme ‘Counting for Planning and Improved Service Delivery’. The enumeration for the 2014 Census was conducted in August/September 2014. The Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) worked closely with different Government Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) as well as Local Governments (LGs) to undertake the census exercise. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

A Case Study of the Teso Sub-Region, Eastern Uganda

Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge Vol. 11 (2), April 2012, pp. 217-224 Role of Indigenous Knowledge in Climate Change Adaptation: A case study of the Teso Sub-Region, Eastern Uganda Anthony Egeru School of Forestry, Environment and Geographical Sciences, Department of Environmental Management, Makerere University, PO Box 7062 Kampala, Uganda Emails: [email protected]/[email protected] Received 20.10.2011, revised 21.12.2011 This study examined the role of indigenous knowledge in climate change adaptation in Uganda with specific focus on the Teso sub-region. Specifically, the study identified indigenous knowledge practices used in climate change adaptation, documented indigenous knowledge in climate observation, and identified constraints to indigenous knowledge use for climate change adaptation. Data was collected using semi-structured questionnaires, individual interviews, focused group discussions and observation of local traditional rites. Local observations confirmed altered climate patterns noticeable from the changes in the planting, weeding and harvesting periods in agriculture, in tree growth, and in wind directions. Farmers still observe the intensity of East-West blowing winds, colour of the clouds in the East, and plant traits for rainfall prediction. In addition, they also rely on the meteorological information disseminated through the local radio stations. Low mastery of indigenous knowledge practices by younger community members and persistently changing weather patterns have challenged community reliance on indigenous knowledge for climate change adaptation. There is need to strengthen dissemination of indigenous knowledge and to integrate modern approaches that strengthen indigenous knowledge in climate change adaptation and resilience. Keywords: Adaptation, Climate change, Indigenous knowledge, Teso Uganda IPC Int. -

Tuesday, 20Th November 2018 – Time of Commencement 2:00 P.M

7TH SITTING OF THE 2ND MEETING OF THE 3RD SESSION OF THE 10TH PARLIAMENT OF UGANDA: TUESDAY, 20TH NOVEMBER 2018 – TIME OF COMMENCEMENT 2:00 P.M. 1. PRAYERS 2. COMMUNICATION FROM THE CHAIR 3. PRESENTATION OF PAPERS: (20 MINUTES) A) EDUCATION SERVICE COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT FOR FINANCIAL YEAR 2017/18 (Parliamentary Commissioner) B) ANNUAL REPORT ON THE STATE OF EQUAL OPPORTUNITIES IN UGANDA FOR FY 2017/2018 (Parliamentary Commissioner) C) PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT, FY 2017/2018 (Parliamentary Commissioner) D) REPORTS OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE FOLLOWING LOCAL GOVERNMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2017: Parliamentary Commissioner) I) KIRUHURA TOWN COUNCIL II) KANUNGU TOWN COUNCIL III) WOBULENZI TOWN COUNCIL IV) MUKONO MUNICIPAL COUNCIL V) KAKIRI TOWN COUNCIL VI) ENTEBBE DIVISION B COUNCIL VII) NKOKONJERU TOWN COUNCIL VIII) BUGONGI TOWN COUNCIL IX) NAKASEKE DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT X) NAKASONGOLA TOWN COUNCIL XI) KIRA MUNICIPAL COUNCIL XII) BUIKWE TOWN COUNCIL XIII) KABALE DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT XIV) KITWE TOWN COUNCIL XV) KANUNGU DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT XVI) BUVUMA DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT 1 XVII) MPIGI DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT XVIII) KAKINDO TOWN COUNCIL XIX) KAMBUGA TOWN COUNCIL XX) BUTAMBALA DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT XXI) WAKISO DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT XXII) MITOOMA TOWN COUNCIL XXIII) RYAKARIMIRA TOWN COUNCIL XXIV) BUVUMA TOWN COUNCIL XXV) KIRA DIVISION COUNCIL XXVI) SEMUTO TOWN COUNCIL XXVII) RWASHAMAIRE TOWN COUNCIL XXVIII) ENDIINZI TOWN COUNCIL XXIX) GOMBE TOWN COUNCIL XXX) -

Funding Going To

% Funding going to Funding Country Name KP‐led Timeline Partner Name Sub‐awardees SNU1 PSNU MER Structural Interventions Allocated Organizations HTS_TST Quarterly stigma & discrimination HTS_TST_NEG meetings; free mental services to HTS_TST_POS KP clients; access to legal services PrEP_CURR for KP PLHIV PrEP_ELIGIBLE Centro de Orientacion e PrEP_NEW Dominican Republic $ 1,000,000.00 88.4% MOSCTHA, Esperanza y Caridad, MODEMU Region 0 Distrito Nacional Investigacion Integral (COIN) PrEP_SCREEN TX_CURR TX_NEW TX_PVLS (D) TX_PVLS (N) TX_RTT Gonaives HTS_TST KP sensitization focusing on Artibonite Saint‐Marc HTS_TST_NEG stigma & discrimination, Nord Cap‐Haitien HTS_TST_POS understanding sexual orientation Croix‐des‐Bouquets KP_PREV & gender identity, and building Leogane PrEP_CURR clinical providers' competency to PrEP_CURR_VERIFY serve KP FY19Q4‐ KOURAJ, ACESH, AJCCDS, ANAPFEH, APLCH, CHAAPES, PrEP_ELIGIBLE Haiti $ 1,000,000.00 83.2% FOSREF FY21Q2 HERITAGE, ORAH, UPLCDS PrEP_NEW Ouest PrEP_NEW_VERIFY Port‐au‐Prince PrEP_SCREEN TX_CURR TX_CURR_VERIFY TX_NEW TX_NEW_VERIFY Bomu Hospital Affiliated Sites Mombasa County Mombasa County not specified HTS_TST Kitui County Kitui County HTS_TST_NEG CHS Naishi Machakos County Machakos County HTS_TST_POS Makueni County Makueni County KP_PREV CHS Tegemeza Plus Muranga County Muranga County PrEP_CURR EGPAF Timiza Homa Bay County Homa Bay County PrEP_CURR_VERIFY Embu County Embu County PrEP_ELIGIBLE Kirinyaga County Kirinyaga County HWWK Nairobi Eastern PrEP_NEW Tharaka Nithi County Tharaka Nithi County -

Youth Realities, Aspirations, Transitions to Adulthood and Opportunity Structures in Uganda’S Dryland Areas

Youth Realities, Aspirations, Transitions to Adulthood and Opportunity Structures in Uganda’s Dryland Areas Brenda Boonabaana, Peace Musiimenta, Margaret Najjingo Mangheni, and Jasper Bakeiha Ankunda Grain Legumes and Alliance Dryland Cereals Table of contents List of tables ................................................................................................................................................ iv List of figures ............................................................................................................................................... iv List of photos ............................................................................................................................................... iv List of boxes ................................................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................................... v Acronyms .................................................................................................................................................... vi Summary ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Method ................................................................................................................................................... -

Pneumococcal Carriage and Antibiotic Susceptibility

F1000Research 2020, 9:1156 Last updated: 22 JUL 2021 RESEARCH ARTICLE Pneumococcal carriage and antibiotic susceptibility patterns in mother-baby pairs in a rural community in Eastern Uganda: a cross-sectional study [version 1; peer review: 1 approved, 1 not approved] Gabriel Madut Akech1, Mercy Naloli 1, Paul Sebwami1, Patrick Kazibwe1, Maureen Atwikiriize1, Julius Onyait2, Paul Oboth1, Julius Nteziyaremye 3, Rebecca Nekaka1, Jacob Stanley Iramiot 4 1Community and Public Health, Busitema University, Mbale, Uganda 2Ngora Health Center IV, Ngora District Local Government, Ngora, Uganda 3Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Busitema University, Mbale, Uganda 4Microbiology and Immunology, Busitema University, Mbale, Uganda v1 First published: 21 Sep 2020, 9:1156 Open Peer Review https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.22238.1 Latest published: 21 Sep 2020, 9:1156 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.22238.1 Reviewer Status Invited Reviewers Abstract Background: Pneumonia poses a significant threat to the lives of 1 2 children below five years old worldwide, contributing to a high number of hospitalizations and death. Morbidity and morbidity are version 1 especially common in children under five and the elderly, although 21 Sep 2020 report report any age group can be affected. This study aimed to estimate pneumococcal carriage and determine antibiotic susceptibility 1. Wilber Sabiti , University of St Andrews, St patterns of the pneumococci isolated from mother-baby pairs in Ngora district after the rollout of the pneumococcal vaccine. We Andrews, UK hypothesized that high carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in 2. Adnan Al-Lahham, School of Applied Medical mothers leads to carriage in their babies and hence a greater chance of contracting pneumonia. -

Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies

Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies Series Editor: Oliver P. Richmond, Professor, School of International Relations, University of St Andrews Editorial Board: Roland Bleiker, University of Queensland, Australia; Henry F. Carey, Georgia State University, USA; Costas Constantinou, University of Keele, UK; A.J.R. Groom, University of Kent, UK; Vivienne Jabri, King’s College London, UK; Edward Newman, University of Birmingham, UK; Sorpong Peou, Sophia University, Japan; Caroline Kennedy-Pipe, University of Sheffield, UK; Professor Michael Pugh, University of Bradford, UK; Chandra Sriram, University of East London, UK; Ian Taylor, University of St Andrews, UK; Alison Watson, University of St Andrews, UK; R.B.J. Walker, University of Victoria, Canada; Andrew Williams, University of St Andrews, UK. Titles include: Susanne Buckley-Zistel CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN UGANDA Remembering after Violence Jason Franks RETHINKING THE ROOTS OF TERRORISM Vivienne Jabri WAR AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF GLOBAL POLITICS James Ker-Lindsay EU ACCESSION AND UN PEACEKEEPING IN CYPRUS Roger MacGinty NO WAR, NO PEACE The Rejuvenation of Stalled Peace Processes and Peace Accords Carol McQueen HUMANITARIAN INTERVENTION AND SAFETY ZONES Iraq, Bosnia and Rwanda Sorpong Peou INTERNATIONAL DEMOCRACY ASSISTANCE FOR PEACEBUILDING The Cambodian Experience Sergei Prozorov UNDERSTANDING CONFLICT BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE EU The Limits of Integration Oliver P. Richmond THE TRANSFORMATION OF PEACE Bahar Rumelili CONSTRUCTING REGIONAL AND GLOBAL ORDER Europe and Southeast Asia Chandra Lekha Sriram PEACE AS GOVERNANCE Stephan Stetter WORLD SOCIETY AND THE MIDDLE EAST Reconstructions in Regional Politics Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies Series Standing Order ISBN 978--1--4039--9575--9 (hardback) & 978--1--4039--9576--6 (paperback) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. -

Heifer International Uganda Covid-19 Impact Study Report

HEIFER INTERNATIONAL UGANDA COVID-19 IMPACT STUDY REPORT PREPARED BY: Paul Muliika | Planning, Monitoring, Learning and Evaluation Manager Abby Bwogi | Regional Monitoring, Learning and Evaluation Manager EAYIP John Ssenyonga | Heifer International Senior Programs Manager MAY–JUNE 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 INTRODUCTION 5 SURVEY PURPOSE 5 METHODOLOGY AND TOOLS 6 RESPONDENT DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS 6 QUANTITATIVE FINDINGS 8 1. EFFECT OF COVID-19 ON FARMER INCOMES 8 2. EFFECT OF COVID-19 ON INFORMAL SAVINGS AND LENDING 12 ASSOCIATION (ISLA) ACTIVITIES 3. EFFECT OF COVID-19 ON FARM AND OFF-FARM PRODUCTION 14 4. EFFECT OF COVID-19 ON ACCESS TO FOOD 16 5. EFFECT OF COVID-19 ON FAMILY DECISION-MAKING 17 6. EFFECT OF COVID-19 ON FAMILY RELATIONSHIPS 19 7. EFFECT OF COVID-19 ON NATURAL RESOURCES 20 8. EFFECT OF COVID-19 ON FAMILY HYGIENE, SANITATION AND 21 HEALTH QUALITATIVE RESULTS 23 9. EFFECT OF COVID-19 ON AGRI-HUB OPERATIONS 23 10. EFFECT OF COVID-19 ON PRIVATE SECTOR OPERATIONS 29 11. EFFECT OF COVID-19 ON PUBLIC SECTOR OPERATIONS 32 12. STRATEGIES ADOPTED BY PROJECTS IN RESPONSE TO COVID-19 34 13. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 36 ANNEX 1: List of People Interviewed 39 ANNEX 2: Key Informant Interview Guide for Private and Public Sector Partners 40 ANNEX 3: Key Informant Interview Guide for Agri-Hubs/Producer Organizations 41 ANNEX 4: Questionnaire for Smallholder Farmers 42 2 HEIFER INTERNATIONAL UGANDA COVID-19 IMPACT STUDY REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION On March 25, 2020, Heifer Uganda suspended all office-based work and staff were requested to work from home following the country’s lockdown to combat the spread of COVID-19. -

(4) of the Constitution Providing for Creation of New Counties

AMMENDED MOTTON FOR RESOLUTTON OF PARLTAMENT UNDER ARTTCLE 179 (4) OF THE CONSTITUTION PROVIDING FOR CREATION OF NEW COUNTIES WHEREAS, Ariicle 179 (a) of the Constitution of the Republic of Ugondo (os omended) provides for the criterio for olterotion of boundories oflor creotion of Administrotive Units including new Counties; AND WHEREAS Section 7 (7) of the Locql Governments Act Cop. 243, (os omended) empowers Porlioment to opprove olternotion of Boundories of/or creotion of o new County; Honoroble Colleogues willTHUS, recoll thot on Tuesdoy 30rn June, 2020,1 moved o motion on the floor of Porlioment for creotion of I5 (Fitteen) Counties thot were opproved by Cobinet hoving received requests from the District Councils of; Kiboole, Kotokwi, Agogo, lsingiro, Kisoro, Nokoseke, Kibogo, Buhweju, Lomwo, Kokumiro, Nokopiripirit, Mubende, Kwonio, Tororo ond Jinjo to creote the following Counties: - l) Buyanja Eost County out of Buyanjo County in Kibaale Distric[ 2) Ngoriom Covnty out of Usuk County in Kotakwi; 3) Agago Wesf County out of Agogo County in Agogo District; 4) Bukonga Norfh County out of Bukongo County in lsingiro District; 5) Bukimbiri County out of Bufumbira County in Kisoro District; 6) Nokoseke Centrol County out of Nokoseke Norfh County in Nokoseke Disfricf 7) Kibogo Wesf County out of Kibogo Eost County in Kbogo District; B) Buhweju West County aut of Buhweju County in Buhweju District; 9) Palobek County out of Lamwo County in Lamwo District; lA)BugongoiziSouth County out of BugongoiziWest County in Kokumiro Districf; I l)Chekwi Eosf County out of Chekwi County in Nokopiripirit District; l2)Buweku/o Soufh County out of Buweku/o County in Mubende Disfricf, l3)Kwanio Norfh County out of Kwonio Counfy in Kwonio Dislricf l )West Budomo Central County out of Wesf Budomo County inTororo Districf; l5)Kogomo Norfh County out of Kogomo County in Jinjo Districf.