Edited by Caroline Sweetman Oxfam Focus on Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019/20 Annual Report and Accounts

The Women’s Budget Group (A Company Limited by Guarantee) Report and Financial Statements For the Year Ended 31 March 2020 Company Registration Number: 04743741 The Women’s Budget Group Contents Contents Legal and administrative information ............................................................................................................. 3 Report of the Management Committee ......................................................................................................... 4 Independent Examiner’s Report to the Management Committee for the year ended 31 March 2020 ....... 11 Statement of Financial Activities for the year ended 31 March 2020............................................................12 Balance Sheet as at 31 March 2020 .............................................................................................................. 13 Notes forming part of the Financial Statements for the year ended 31 March 2020 .............................. 14-18 2 Prepared by ExcluServ Ltd The Women’s Budget Group Report of the Management Committee Directors: Janet Veitch (Chair from September 2019) Scarlet Harris Jerome De Henau Susan Felicity Himmelweit Angela Rose O'Hagan Ruth Eleanor Pearson Polly Trenow Annalise Verity Johns Patricia Anne Simons (Treasurer) Sarah Marie Hall Charlotte Woodworth (appointed 19 September 2019) Elizabeth Law (appointed 19 September 2019) Jules Allen (appointed 19 September 2019) Kimberly McIntosh (appointed 19 September 2019) Karissa Singh (appointed 19 September 2019) Rachael Revesz (appointed -

11 — 27 August 2018 See P91—137 — See Children’S Programme Gifford Baillie Thanks to All Our Sponsors and Supporters

FREEDOM. 11 — 27 August 2018 Baillie Gifford Programme Children’s — See p91—137 Thanks to all our Sponsors and Supporters Funders Benefactors James & Morag Anderson Jane Attias Geoff & Mary Ball The BEST Trust Binks Trust Lel & Robin Blair Sir Ewan & Lady Brown Lead Sponsor Major Supporter Richard & Catherine Burns Gavin & Kate Gemmell Murray & Carol Grigor Eimear Keenan Richard & Sara Kimberlin Archie McBroom Aitken Professor Alexander & Dr Elizabeth McCall Smith Anne McFarlane Investment managers Ian Rankin & Miranda Harvey Lady Susan Rice Lord Ross Fiona & Ian Russell Major Sponsors The Thomas Family Claire & Mark Urquhart William Zachs & Martin Adam And all those who wish to remain anonymous SINCE Scottish Mortgage Investment Folio Patrons 909 1 Trust PLC Jane & Bernard Nelson Brenda Rennie And all those who wish to remain anonymous Trusts The AEB Charitable Trust Barcapel Foundation Binks Trust The Booker Prize Foundation Sponsors The Castansa Trust John S Cohen Foundation The Crerar Hotels Trust Cruden Foundation The Educational Institute of Scotland The Ettrick Charitable Trust The Hugh Fraser Foundation The Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund Margaret Murdoch Charitable Trust New Park Educational Trust Russell Trust The Ryvoan Trust The Turtleton Charitable Trust With thanks The Edinburgh International Book Festival is sited in Charlotte Square Gardens by the kind permission of the Charlotte Square Proprietors. Media Sponsors We would like to thank the publishers who help to make the Festival possible, Essential Edinburgh for their help with our George Street venues, the Friends and Patrons of the Edinburgh International Book Festival and all the Supporters other individuals who have donated to the Book Festival this year. -

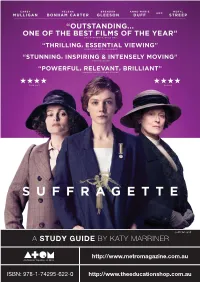

Suffragette Study Guide

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-622-0 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 106 minutes » SUFFRAGETTE Suffragette (2015) is a feature film directed by Sarah Gavron. The film provides a fictional account of a group of East London women who realised that polite, law-abiding protests were not going to get them very far in the battle for voting rights in early 20th century Britain. click on arrow hyperlink CONTENTS click on arrow hyperlink click on arrow hyperlink 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 19 8. Never surrender click on arrow hyperlink 3 STORY 20 9. Dreams 6 THE SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT 21 EXTENDED RESPONSE TOPICS 8 CHARACTERS 21 The Australian Suffragette Movement 10 ANALYSING KEY SEQUENCES 23 Gender justice 10 1. Votes for women 23 Inspiring women 11 2. Under surveillance 23 Social change SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2015 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION 12 3. Giving testimony 23 Suffragette online 14 4. They lied to us 24 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS 15 5. Mrs Pankhurst 25 APPENDIX 1 17 6. ‘I am a suffragette after all.’ 26 APPENDIX 2 18 7. Nothing left to lose 2 » CURRICULUM LINKS Suffragette is suitable viewing for students in Years 9 – 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, Civics and Citizenship, History, Media, Politics and Sociology. Links can also be made to the Australian Curriculum general capabilities: Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability and Ethical Understanding. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ and curriculum outlines relevant to these studies in their state or territory. -

University of Suffolk News

UNIVERSITY OF SUFFOLK NEWS WELCOME Welcome to the first newsletter of 2019. We remain in a This year marks the 25th challenging and changing environment, with the results anniversary of our provision of the Augur Review expected this month, Brexit in Early Childhood looming, recruitment competition ongoing, essay mills, studies—something that unconditional offers and grade inflation all remaining we should all be proud of high on government agendas. and use to demonstrate how we integrate with our It would be easy to be despondent but as a senior team community through using we remain optimistic. We have concluded the Schools our expertise. and Directorates strategic planning round, and are now looking at the shape of our estate and IT along with our In December we ‘installed’ people strategy to enable us to be in the best position our first Chancellor— possible to weather the turbulent times ahead. a fantastic way to round off 2018 as we continue to mature as a young institution. Our students and their education remain our key Dr Helen Pankhurst gave her time freely for staff focus, and the task and finish groups will be reporting through a lecture and with students through a visit back by Easter with changes made ready for the next to the SU. She plans to engage with us through the academic year. Many of you are engaged in these and year, mainly at graduation ceremonies, at University they are already reporting good discussions and ideas Court and with a further lecture; alongside this she will in the key areas under consideration. -

Category: Arts, Culture Or Sport Campaign Company: Fido PR and Pankhurst Trust Entry Title: Deeds Not Words

Category: Arts, Culture or Sport Campaign Company: Fido PR and Pankhurst Trust Entry title: Deeds Not Words Brief and objectives: 2018 represents 100yrs since the first women won the vote. The Pankhurst Centre is the former home of Emmeline Pankhurst, the birthplace of the suffragette movement, a Grade II* listed building, the UK’s only museum dedicated to female suffrage; and yet receives no public funding. #Vote100 would be a key time to raise its profile and try to end its fragile state and uncertain future. In August it will make a Heritage Lottery Fund submission. Profile raising would add strength to this and provide support to the fundraising activity required for the match-funding. Raise awareness of the Pankhurst to highlight its story and place as one of the nation’s most important heritage sites. Rationale behind campaign, including research and planning: Legislation granting the vote was passed 6 February 1819, HLF bid submitted August 2018, 100th anniversary of first women voting 14 December 2018. These milestones would frame our campaign. We needed to bring the story to Manchester; research highlighting high level of London-centred activity. Emmeline Pankhurst is recognised globally, however, relatively low awareness that she was from Manchester. Emmeline’s great-granddaughter, Helen Pankhurst, would speak on behalf of the Pankhurst. The Pankhurst fought against the bulldozers in the 1970s; the women behind it are passionate, bold and fearless. The suffragette story, in depth, had been largely untold. Resources and the Pankhurst opening hours would be limited. Strategy and tactics, including creativity and innovation: We’d place the Pankhurst and its powerful story on the map and align this with the fact that this iconic, hugely historically significant museum, is supported not by public funding, but by the goodwill of volunteers and ad hoc donations. -

PDF Download 2.9MB

WOMEN ACT! THE TRAGEDIAN’S DAUGHTERS FLORA CLICKMANN TWO TENNIS STARS DANGEROUS WOMEN – MAD OR BAD? MRS MAURICE LUBBOCK MARIE CHARLOTTE CARMICHAEL STOPES ANNIE BESANT TWO WOMEN ARTISTS No. 221 SUMMER www.norwoodsociety.co.uk 2018 CONTENTS WOMEN ACT! P 1 THE TRAGEDIAN’S DAUGHTERS P 3 FLORA CLICKMANN P 10 TWO TENNIS STARS P 12 DANGEROUS WOMEN – MAD OR BAD? P 16 MRS MAURICE LUBBOCK P 26 MARIE CHARLOTTE CARMICHAEL STOPES P 29 ANNIE BESANT P 33 TWO WOMEN ARTISTS OF UPPER NORWOOD P 34 PLANNING REPORT P 44 ANNUAL REPORT P 46 LOCAL HISTORY – FORTHCOMING EVENTS P 49 Special thanks to Barbara Thomas for co-ordinating this edition of the Review. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Chairman Committee Stuart Hibberd [email protected] Anna-Katrina Hastie Vice Chairman Planning Matters Jerry Green Marian Girdler Philip Goddard (Acting) Treasurer (Contact through Secretary) Stuart Hibberd [email protected] Secretary Local History/Walks/Talks Stephen Oxford, 9 Grangecliffe Alun and Barbara Thomas Gardens, London, SE25 6SY [email protected] [email protected] 020 84054390 Membership Secretary: Ruth Hibberd membership@norwood EDITOR: Stephen Oxford society.co.uk Website: www.norwoodsociety.co.uk Registered with the Charity Commission 285547 Norwood Review Summer 2018 WOMEN ACT! On 6 February 2018 celebrations took place to commemorate one hundred years since the Representation of the Peoples Act. The Museum of London has put on a free exhibition ‘Votes for Women’ which runs until 6 January 2019. The Museum itself holds items collected from suffragette activity. Also, in 2018 the LSE Library (now home of the Women’s Library) began ‘A Centenary Exploration’ with events and activities, and another free exhibition from 23 April to 27 August. -

Senior -Newsletter- 25 Jan 19.Pdf

S E N I O R N E W S L E T T E R Friday 25 January 2019 DATES FOR YOUR DIARY Tuesday 29 January Year 9 Immunisations from 9.30am Wednesday 30 January Year 11 Parent Teacher Meetings 4.30pm Friday 1 February FOSC Quiz Night 7.00pm Tuesday 5 February House Music and Dance Competition Wednesday 6 February Year 13 MFL Conference Open Evening 6.15pm Tuesday 12 February Year 7 Parent Teacher Meeting 4.30pm FOSC Committee Meeting 7.30pm Wednesday 13 February Year 11-13 Art Trip to London Gallery Outlook Costa Rica Talk 6.30pm Thursday 14 February Siena Society—Nick Pulsford Friday 15 February Year 10 Theatre Trip to Macbeth NEXT NEWSLETTER FRIDAY 15 FEBRUARY FROM THE HEADMISTRESS Good afternoon Happy new year to everyone and welcome to the Spring term. The girls are braving the cold weather and have made a fine start to their lessons and activities. The Sixth Form girls were pleased to return to their common room which was redecorated over the break and plans are underway for further changes and new furniture later in the year. We know that a comfortable, happy space is very important for these girls who, having just received such wonderful university offers, now have a time of important and careful preparation. This first three weeks has included a beautiful Epiphany mass, some very successful cross country running, a talk for Years 11-13 on a volunteer opportunity in the summer, a thoughtful assembly on Holocaust Memorial Day, and an inspiring talk by Helen Pankhurst, the granddaughter of Sylvia Pankhurst, on the history and impact of all those who fought for the vote for women. -

MARCH PANKHURST.Indd

REPORT ‘The WI has POWER’ IN THESE TURBULENT TIES, SAYS DR HELEN PANKHURST CBE, AUTHOR, ACTIVIST AND DESCENDANT OF SUFFRAGETTES, WE SHOULD ALL BE ASKING ‘WHAT CAN I DO?’ Words ELEANOR WILSON Photography JANE MILES, THE BRENTWOOD BELLES, ESSEX FEDERATION s a women’s rights wouldn’t allow women entry campaigner, writer and in 1913, the movement was Aacademic, the great- also about ‘sisterhood, fun and granddaughter of suffragette coming together’. Remind you icon Emmeline Pankhurst of anything…? and granddaughter of Sylvia Helen has appeared at Pankhurst, Helen (right) several WI events over the was in high demand last years and detailed its early year as Britain celebrated campaign work in her book, the centenary of the Act that Deeds Not Words: The Story granted some UK women of Women’s Rights, Then the right to vote. and Now (Sceptre), Speaking to WI Life at the published in 2018. Essex Federation Autumn ‘I love the WI,’ she says. County Event, Helen, newly ‘It’s quirky. It’s women’s space appointed Commander of the with all the complexity of what Order of the British Empire other women are: political (CBE) in the 2019 New Year engagement, the domestic Honours, for services to space, a lot of arguments about Gender Equality, says: ‘It’s massive. The level of interest has how best to do all of this, and a lot of support.’ been much higher than I think I expected.’ What does she hope to see from the WI in future? ‘I’d like As well as having addressed the WI, Helen has spoken to see them as more confident in their political voice. -

Download SCHG Journal Volume 42 WEB

Social History in Museums Volume 42 SHCG Social History in Museums Volume Social History in Museums Volume 42 Social History in Museums Special issue: The Centenary of the Representation of the People Act (1918) in Museums. Guest edited by Dr Gillian Murphy, Curator for Equality, Rights and Citizenship, LSE Library. Edited by Amy Rowbottom. Volume 42 (2018) Published by the Social History Curators Group 2018 ISSN 1350-9551 © SHCG and contributors Contents Gillian Murphy Guest Editor’s Foreword 5 Guest Introduction Dr Helen The Representation of the People Act 7 Pankhurst and the Pankhurst Centre Collecting and Interpreting Collections Mari Takayanagi Voice and Vote: Women’s Place in Parliament 9 and Melanie Unwin Helen Antrobus First in the Fight: The story of the People’s History 17 and Jenny Museum’s Manchester suffragette banner Mabbott Kitty Ross and Leonora Cohen Suffragette collection: 23 Nicola Pullan Breaking out of the display case Rebecca Odell Dead Women Can’t Vote: How Hackney Museum and 31 the East End Women’s Museum are creating a community curated exhibition exploring women-led activism and social change post 1918 Donna Moore The March of Women: Glasgow Women’s Library’s living 39 and breathing archive out on the streets Kirsty Fife “Any More Picketing and I’ll Leave”: Reflections on 49 Researching Women’s Protest and Politics in the Daily Herald Archive at the National Science and Media Museum Exhibition Reviews Christine Alford Review of Votes for Women Display 57 Claire Madge Exhibition Review of Votes for Women 61 Museum of London, 2 February 2018 – 6 January 2019 and Shades of Suffragette Militancy: Museum of London, 2 February 2018 – 25 April 2018 Gemma Elliott Exhibition Review of Our Red Aunt 63 Glasgow Women’s Library, 2nd February 2018 – 17th March 2018 Book Review Christine Alford Soldiers and Suffragettes: 65 The Photography of Christina Broom 5 Guest Editor’s Foreword Tuesday 6 February 2018 saw an important day of celebrations marking the centenary of an act that granted votes for some women. -

A Statue for Sylvia Pankhurst Brochure

Patrons: Maxine Peake, Baroness primarily associated with the fight for a statue for Sylvia Pankhurst Margaret Prosser, Lord Chris Smith votes for women, less well known is Committee: Philippa Clark, Professor her active involvement in other causes Mary Davis, Megan Dobney, Barbara both domestic and international. Switzer Sylvia trained as an artist. Whilst Late Patrons: Rodney Bickerstaffe, painting and thus documenting Baroness Brenda Dean, Richard working women in factories, mills and Pankhurst potteries she wrote: Patron Baroness Brenda Dean It was 20 years ago, April 1998, that the story of A Statue for Sylvia started. Patron Maxine Peake Showing some young friends around the sights of Westminster and stopping in front of the memorial, adjacent to “Mothers came to me with their wasted the House of Lords, to Emmeline and little ones. I saw starvation look at me Christabel Pankhurst and the women from patient eyes. I knew then that I who were imprisoned and force fed should never return to my art.” because of their determination to fight Sylvia was expelled from the Women’s for the right of women to vote, Sylvia Social and Political Union by her sister, Pankhurst was notably absent. Christabel, endorsed by her mother People may know about Sylvia the Emmeline and this is why she is not suffragette but perhaps be unaware represented on the memorial despite that she doesn’t feature on this also being imprisoned and force fed. memorial to the suffragettes. She wrote They were opposed to her the definitive history of the suffragette determination to improve the movement and whilst her name is conditions of the poor and her belief effective campaigning tool. -

Proceedings of the Textile Society of America 17Th Biennial Symposium, October 15-17, 2020--Full Program with Abstracts & Bios

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 10-2020 Hidden Stories/Human Lives: Proceedings of the Textile Society of America 17th Biennial Symposium, October 15-17, 2020--Full Program with Abstracts & Bios Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. WELCOME PAGE Be Part of the Conversation Tag your posts on social media #TSAHiddenStoriesHumanLives #TSA2020 Like us on Facebook: @textilesocietyofamerica Follow us on Instagram: @textilesociety Attendee Directory The attendee directory is available through Crowd Compass If you have any questions, please contact Caroline Hayes Charuk: [email protected]. Please note that the information published in this program and is subject to change. Please check textilesocietyofamerica.org for the most up-to-date infor- mation. TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Symposium . 1 The Theme .......................................................1 Symposium Chairs ................................................1 Symposium Organizers . .2 Welcome from TSA President, Lisa Kriner . 4 Donors & Sponsors . 8 Symposium Schedule at a Glance . 11 Welcome from the Symposium Program Co-Chairs . 12 Keynote & Plenary Sessions . 14 Sanford Biggers..................................................14 Julia Bryan-Wilson................................................15 Jolene K. Rickard.................................................16 Biennial Symposium Program . -

Women in Ethiopia | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History

Women in Ethiopia Meron Zeleke Eresso, Department of Social Anthropology, Addis Ababa University https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.541 Published online: 25 March 2021 Summary There are number of Ethiopian women from different historical epochs known for their military prowess or diplomatic skills, renowned as religious figures, and more. Some played a significant role in fighting against the predominant patriarchal value system, including Ye Kake Yewerdewt in the early 19th century. Born in Gurage Zone, she advocated for women’s rights and condemned many of the common cultural values and practices in her community, such as polygamy, exclusive property inheritance rights for male children and male family members, and the practice of arranged and forced marriage. Among the Arsi Oromo, women have been actively engaged in sociojudicial decision-making processes, as the case of the Sinqee institution, a women-led customary institution for dispute resolution, shows. This reflects the leading role and status women enjoyed in traditional Arsi Oromo society, both within the family and in the wider community. In Harar, a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in eastern Ethiopia, female Muslim scholars have played a significant role in teaching and handing down Islamic learning. One such religious figure was the Harari scholar Ay Amatullāh (1851–1893). Another prominent female religious figure from Arsi area, Sittī Momina (d. 1929), was known for her spiritual practices and healing powers. A shrine in eastern Ethiopia dedicated to Sittī Momina is visited by Muslim and Christian pilgrims from across the country. Despite the significant and multifaceted role played by women in the Ethiopian community, however, there is a paucity of data illustrating the place women had and have in Ethiopia’s cultural and historical milieu.