We Are Makers End of Project Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sheffield Street Tree Strategy Development Group

Sheffield Street Tree Strategy Development Group i-Tree Eco Stratified Inventory Report November 2019 The Authors James Watson - Treeconomics Reviewed By: Danielle Hill - Treeconomics This assessment was carried out by Treeconomics 1 Executive Summary In this report, the street trees in Sheffield have been assessed based on the benefits that they provide to society. These trees, which form part of Sheffield’s natural capital, are generally recognised and appreciated for their amenity, presence and stature in the cityscape and surroundings. However, society is often unaware of the many other benefits (or ecosystem services) that trees provide to those living in our towns and cities. The trees in and around our urban areas (together with woodlands, shrubs, hedges, open grass, green space and wetland) are collectively known as the ‘urban forest’. This urban forest improves our air, protects watercourses, saves energy, and improves economic sustainability1. There are also many health and well-being benefits associated with being in close proximity to trees and there is a growing research base to support this2. Sheffield’s street trees are a crucial part of the city’s urban forest, rural areas and woodlands. Many of the benefits that Sheffield’s urban forest provides are offered through its street trees. Economic valuation of the benefits provided by our natural capital3 (including the urban forest) can help to mitigate for development impacts, inform land use changes and reduce any potential impact through planned intervention to avoid a net loss of natural capital. Such information can be used to help make better management decisions. Yet, as the benefits provided by such natural capital are often poorly understood, they are often undervalued in the decision making process. -

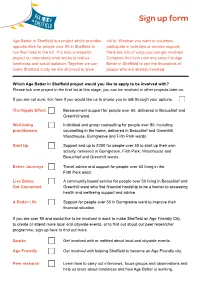

Sign up Form

Sign up form Age Better in Sheffield is a project which provides old in. Whether you want to volunteer, opportunities for people over 50 in Sheffield to participate in activities or receive support, live their lives to the full. It is also a research there are lots of ways you can get involved. project to understand what works to reduce Complete this form now and send it to Age loneliness and social isolation. Together we can Better in Sheffield to join the thousands of make Sheffield a city we are all proud to grow people who are already involved. Which Age Better in Sheffield project would you like to apply to be involved with? Please tick one project in the first list at this stage, you can be involved in other projects later on. If you are not sure, tick here if you would like us to phone you to talk through your options. The Ripple Effect Bereavement support for people over 50, delivered in Beauchief and Greenhill ward. Well-being Individual and group counselling for people over 50, including practitioners counselling in the home, delivered in Beauchief and Greenhill, Woodhouse, Burngreave and Firth Park wards. Start Up Support and up to £200 for people over 50 to start up their own activity, delivered in Burngreave, Firth Park, Woodhouse and Beauchief and Greenhill wards. Better Journeys Travel advice and support for people over 50 living in the Firth Park ward. Live Better, A community based service for people over 50 living in Beauchief and Get Connected Greenhill ward who find financial hardship to be a barrier to accessing health and wellbeing support and advice. -

Agenda Item 3

Agenda Item 3 Minutes of the Meeting of the Council of the City of Sheffield held in the Council Chamber, Town Hall, Pinstone Street, Sheffield S1 2HH, on Wednesday 5 December 2012, at 2.00 pm, pursuant to notice duly given and Summonses duly served. PRESENT THE LORD MAYOR (Councillor John Campbell) THE DEPUTY LORD MAYOR (Councillor Vickie Priestley) 1 Arbourthorne Ward 10 Dore & Totley Ward 19 Mosborough Ward Julie Dore Keith Hill David Barker John Robson Joe Otten Isobel Bowler Jack Scott Colin Ross Tony Downing 2 Beauchiefl Greenhill Ward 11 East Ecclesfield Ward 20 Nether Edge Ward Simon Clement-Jones Garry Weatherall Anders Hanson Clive Skelton Steve Wilson Nikki Bond Roy Munn Joyce Wright 3 Beighton Ward 12 Ecclesall Ward 21 Richmond Ward Chris Rosling-Josephs Roger Davison John Campbell Ian Saunders Diana Stimely Martin Lawton Penny Baker Lynn Rooney 4 Birley Ward 13 Firth Park Ward 22 Shiregreen & Brightside Ward Denise Fox Alan Law Sioned-Mair Richards Bryan Lodge Chris Weldon Peter Price Karen McGowan Shelia Constance Peter Rippon 5 Broomhill Ward 14 Fulwood Ward 23 Southey Ward Shaffaq Mohammed Andrew Sangar Leigh Bramall Stuart Wattam Janice Sidebottom Tony Damms Jayne Dunn Sue Alston Gill Furniss 6 Burngreave Ward 15 Gleadless Valley Ward 24 Stannington Ward Jackie Drayton Cate McDonald David Baker Ibrar Hussain Tim Rippon Vickie Priestley Talib Hussain Steve Jones Katie Condliffe 7 Central Ward 16 Graves Park Ward 25 Stockbridge & Upper Don Ward Jillian Creasy Ian Auckland Alison Brelsford Mohammad Maroof Bob McCann Philip Wood Robert Murphy Richard Crowther 8 Crookes Ward 17 Hillsborough Ward 26 Walkey Ward Sylvia Anginotti Janet Bragg Ben Curran Geoff Smith Bob Johnson Nikki Sharpe Rob Frost George Lindars-Hammond Neale Gibson 9 Darnall Ward 18 Manor Castle Ward 27 West Ecclesfield Ward Harry Harpham Jenny Armstrong Trevor Bagshaw Mazher Iqbal Terry Fox Alf Meade Mary Lea Pat Midgley Adam Hurst 28 Woodhouse Ward Mick Rooney Jackie Satur Page 5 Page 6 Council 5.12.2012 1. -

Burngreave & Fir Vale

Burngreave & Fir Vale Summary of Evaluation Work SECTION ONE - BACKGROUND Burngreave and Firvale Sure Start programme was agreed December 2000. Staff were in post April 2001 services were delivered May/June 2001. AREA DESCRIPTION The Burngreave and Firvale Sure Start area is diverse and encompasses a range of different languages, cultures and religions. There is a transient population within the area which includes two Mother and Baby Units that take parents from outside of Sheffield and two Women’s Refuges. The area also houses the largest asylum seeking population in Sheffield. The area is a ‘New Deal For Communities’ area and is therefore seeing much regeneration. There are many new projects and schemes springing up, all seeking to recruit new workers and involve local people. The area suffers from poor media coverage due to gun crime and a drugs culture. The area has a negative image and services are struggling to recruit to the area. Since 2002 Burngreave and Firvale Sure Start programme has never been fully staffed and we have had to have agency staff for a number of services. Other services such as health services and New Deal are struggling to recruit to the area. The area is seen as a difficult area to work.. Burngreave and Firvale Sure Start programme is the largest in Sheffield being approved with 1049 under 4’s at the time - numbers are presently 1150. Although it is the largest programme in the city, Burngreave and Firvale Sure Start does not have the largest revenue budget or get the same amount of funding per child as other Sure Start programmes in the city. -

Fxstandardukpublictimetables.Rpt

Stagecoach in Yorkshire Days of Operation MONDAY TO FRIDAY Commencing 7th March 2021 Service Number 088 Service Description Smithy Wood - Bents Green Service No. 88 88 88 88 88 88 788 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 Sch S Ecclesfield, Green Lane 0445 0534 0604 0634 0654 0714 - 0733 0752 0807 0820 0835 0846 0857 0909 0921 0932 0944 0956 1007 Firth Park, Sicey Avenue 0455 0544 0614 0644 0704 0724 - 0743 0802 0817 0831 0846 0857 0908 0920 0932 0943 0955 1007 1018 Burngreave Rd, Arnold Clark 0503 0552 0622 0652 0712 0732 - 0752 0811 0826 0840 0855 0906 0917 0929 0941 0952 1004 1016 1027 Sheffield, Snig Hill (In) CG9 0513 0602 0632 0702 0722 0742 0752 0802 0821 0836 0850 0905 0916 0927 0939 0951 1002 1014 1026 1037 Hunters Bar/Neill Road 0522 0611 0641 0711 0731 0751 0811 0811 0831 0846 0901 0916 0927 0939 0951 1003 1015 1027 1039 1051 Brincliffe, Lay-by 0525 0614 0644 0714 0734 0754 0815 0814 0834 0849 0904 0919 0931 0943 0955 1007 1019 1031 1043 1055 Opp High Storrs School - - - - - - 0817 - - - - - - - - - - - - - Service No. 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 88 Ecclesfield, Green Lane 1016 1028 1040 1052 1103 1114 1126 1138 1150 1202 1214 1226 1238 1250 1302 1315 1327 1339 1351 1403 Firth Park, Sicey Avenue 1027 1039 1051 1103 1114 1125 1137 1149 1201 1213 1225 1237 1249 1301 1313 1326 1338 1350 1402 1414 Burngreave Rd, Arnold Clark 1036 1048 1100 1112 1123 1134 1146 1158 1210 1222 1234 1246 1258 1310 1322 1335 1347 1359 1411 1423 Sheffield, Snig Hill (In) CG9 1046 1058 1110 1122 1133 1144 1156 1208 1220 1232 1244 1256 1308 1320 1332 1345 1357 1409 1421 1433 Hunters Bar/Neill Road 1102 1114 1126 1138 1150 1202 1214 1226 1238 1250 1302 1314 1326 1338 1350 1403 1415 1427 1439 1451 Brincliffe, Lay-by 1107 1119 1131 1143 1155 1207 1219 1231 1243 1255 1307 1319 1331 1343 1355 1407 1419 1431 1443 1455 Opp High Storrs School - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Service No. -

Burngreave New Deal for Communities and Line Managed by Activity Sheffield

active BURNGREAVE Sport & Physical Activity for Adults Intro The Active Burngreave Taskforce aims to encourage and support the people of Burngreave to be more physically active. The aim of this directory is to provide local information on sport and physical activity clubs, groups and activities in the Burngreave area. Did you know? On a local level, physical inactivity is estimated to be causing 41 premature deaths per year in the Burngreave area! But the good news is: You can significantly reduce this risk by doing the recommended minimum amount of physical activity to benefit health. That is: • 30 minutes of moderate exercise, 5 times a week for adults and • 60 minutes of moderate exercise, 7 times a week for children A wide range of activities can make up this activity including walking to school or the shops, gardening, sport, housework, dancing and cycling. Please note: All information is correct at the time of going to print. It is the responsibility of the parent / guardian to ensure that coaches are suitably qualified and police checked, prior to participating. Sheffield City Council cannot be held responsible for any accidents, injuries or loss that may occur whilst undertaking an activity. 2 Contents Aerobics 6 Gardening & Conservation 9 Badminton 6 Health Basketball 6 & Fitness 9 Bowls 6 Martial Arts 10 Chairobics 7 Running 10 Cricket 7 Social Groups 10 Dance 8 Walking 11 Disability Yoga 11 Groups 8 Football 8 3 Useful Local Contacts Michala Spacey Courtney Stirling Burngreave Sports Development Project Co-ordinator Centre -

Council Minutes

Minutes of the Meeting of the Council of the City of Sheffield held on Wednesday 12 August 2020, at 2.00 pm, as a remote meeting in accordance with the provisions of The Local Authorities and Police and Crime Panels (Coronavirus) (Flexibility of Local Authority and Police and Crime Panel Meetings) (England and Wales) Regulations 2020, and pursuant to notice duly given and Summonses duly served. PRESENT THE LORD MAYOR (Councillor Tony Downing) THE DEPUTY LORD MAYOR (Councillor Gail Smith) 1 Beauchief & Greenhill Ward 10 East Ecclesfield Ward 19 Nether Edge & Sharrow Ward Simon Clement-Jones Vic Bowden Peter Garbutt Bob Pullin Moya O'Rourke Jim Steinke Richard Shaw Alison Teal 2 Beighton Ward 11 Ecclesall Ward 20 Park & Arbourthorne Bob McCann Roger Davison Julie Dore Chris Rosling-Josephs Barbara Masters Jack Scott Sophie Wilson Shaffaq Mohammed 3 Birley Ward 12 Firth Park Ward 21 Richmond Ward Denise Fox Abdul Khayum Mike Drabble Bryan Lodge Alan Law Dianne Hurst Karen McGowan Abtisam Mohamed 4 Broomhill & Sharrow Vale Ward 13 Fulwood Ward 22 Shiregreen & Brightside Ward Angela Argenzio Andrew Sangar Dawn Dale Kaltum Rivers Cliff Woodcraft Peter Price Garry Weatherall 5 Burngreave Ward 14 Gleadless Valley Ward 23 Southey Ward Jackie Drayton Cate McDonald Mike Chaplin Talib Hussain Paul Turpin Tony Damms Mark Jones Jayne Dunn 6 City Ward 15 Graves Park Ward 24 Stannington Ward Douglas Johnson Ian Auckland David Baker Ruth Mersereau Sue Auckland Penny Baker Martin Phipps Steve Ayris Vickie Priestley 7 Crookes & Crosspool Ward 16 Hillsborough Ward 25 Stocksbridge & Upper Don Ward Tim Huggan Bob Johnson Jack Clarkson Mohammed Mahroof George Lindars-Hammond Julie Grocutt Anne Murphy Josie Paszek 8 Darnall Ward 17 Manor Castle Ward 26 Walkley Ward Mazher Iqbal Terry Fox Ben Curran Mary Lea Sioned-Mair Richards Zahira Naz 9 Dore & Totley Ward 18 Mosborough Ward 27 West Ecclesfield Ward Joe Otten Tony Downing Alan Hooper Colin Ross Kevin Oxley Adam Hurst Martin Smith Gail Smith Mike Levery 28 Woodhouse Ward Mick Rooney Paul Wood Page 137 Council 12.08.2020 1. -

State of Sheffield 03–16 Executive Summary / 17–42 Living & Working

State of Sheffield 03–16 Executive Summary / 17–42 Living & Working / 43–62 Growth & Income / 63–82 Attainment & Ambition / 83–104 Health & Wellbeing / 105–115 Looking Forwards 03–16 Executive Summary 17–42 Living & Working 21 Population Growth 24 People & Places 32 Sheffield at Work 36 Working in the Sheffield City Region 43–62 Growth & Income 51 Jobs in Sheffield 56 Income Poverty in Sheffield 63–82 Attainment & Ambition 65 Early Years & Attainment 67 School Population 70 School Attainment 75 Young People & Their Ambitions 83–104 Health & Wellbeing 84 Life Expectancy 87 Health Deprivation 88 Health Inequalities 1 9 Premature Preventable Mortality 5 9 Obesity 6 9 Mental & Emotional Health 100 Fuel Poverty 105–115 Looking Forwards 106 A Growing, Cosmopolitan City 0 11 Strong and Inclusive Economic Growth 111 Fair, Cohesive & Just 113 The Environment 114 Leadership, Governance & Reform 3 – Summary ecutive Ex State of Sheffield State Executive Summary Executive 4 The State of Sheffield 2016 report provides an Previous Page overview of the city, bringing together a detailed Photography by: analysis of economic and social developments Amy Smith alongside some personal reflections from members Sheffield City College of Sheffield Executive Board to tell the story of Sheffield in 2016. Given that this is the fifth State of Sheffield report it takes a look back over the past five years to identify key trends and developments, and in the final section it begins to explore some of the critical issues potentially impacting the city over the next five years. As explored in the previous reports, Sheffield differs from many major cities such as Manchester or Birmingham, in that it is not part of a larger conurbation or metropolitan area. -

SOUTH YORKSHIRE KNIFE CRIME STRATEGY 2018/21 2 South Yorkshire Knife Crime Strategy

South Yorkshire Knife Crime Strategy 1 SOUTH YORKSHIRE KNIFE CRIME STRATEGY 2018/21 2 South Yorkshire Knife Crime Strategy BY WORKING TOGETHER WE CAN CREATE RESILIENT, STRONG COMMUNITIES AND BE MUCH MORE EFFECTIVE THAN EVER BEFORE. South Yorkshire Knife Crime Strategy 3 Contents Foreword 5 Partnerships 32 Operation Fortify 6 Delivery 34 Our beliefs 8 Challenges ............................................ 34 Governance .......................................... 34 Knife crime 11 Our vision ............................................. 35 Performance 12 Our aims ............................................... 35 National overview ................................. 12 Our objectives 36 South Yorkshire overview ..................... 14 Prepare ................................................. 37 Perception 16 Prevent ................................................. 38 Why have we seen a rise? .................... 16 Protect .................................................. 39 Pursue .................................................. 40 Problems 18 Our outcomes 41 What is the relationship between gangs and knife crime? ........................ 18 Prepare ................................................. 41 Youth offending .................................... 20 Prevent ................................................. 41 Night-time economy ............................. 21 Protect .................................................. 42 Habitual knife carriers ........................... 22 Pursue ................................................. -

Birley/Beighton/Broomhill and Sharrow Vale

State of Sheffield Sheffield of State State of Sheffield2018 —Sheffield City Partnership Board Beauchief and Greenhill/ 2018 Birley/Beighton/Broomhill and Sharrow Vale/Burngreave/ City/Crookes and Crosspool/ Darnall/Dore and Totley /East Ecclesfield/Firth Park/ Ecclesall/Fulwood/ Gleadless Valley/Graves Park/ Sheffield City Partnership Board Hillsborough/Manor Castle/ Mosborough/ Nether Edge and Sharrow/ Park and Arbourthorne/ Richmond/Shiregreen and Brightside/Southey/ Stannington/Stocksbridge and Upper Don/Walkley/ West Ecclesfield/Woodhouse State of Sheffield2018 —Sheffield City Partnership Board 03 Foreword Chapter 03 04 (#05–06) —Safety & Security (#49–64) Sheffield: Becoming an inclusive Chapter 04 Contents Contents & sustainable city —Social & Community (#07–08) Infrastructure (#65–78) Introduction (#09–12) Chapter 05 —Health & Wellbeing: Chapter 01 An economic perspective —Inclusive & (#79–90) Sustainable Economy (#13–28) Chapter 06 —Looking Forwards: Chapter 02 State of Sheffield 2018 The sustainability & —Involvement & inclusivity challenge Participation (#91–100) 2018 State of Sheffield (#29–48) 05 The Partnership Board have drawn down on both national 06 Foreword and international evidence, the engagement of those organisations and institutions who have the capacity to make a difference, and the role of both private and social enterprise. A very warm welcome to both new readers and to all those who have previously read the State of Sheffield report which From encouraging the further development of the ‘smart city’, is now entering -

'People Keeping Well in Their Community' (PKW)

Briefing Note What is ‘People Keeping Well’? ‘People Keeping Well in their Community’ is community-based prevention activity that can help to prevent and delay people needing to access health and social care services. It is one of Sheffield’s approaches to Social Prescribing. It’s about resolving social issues and connecting people to ‘things that matter to them’ locally which will reduce the risk and/or decline of poor health and wellbeing, so that people: • are more connected – they have made friends and have a peer network for support • are more resilient – they have coping mechanisms to deal with ‘life issues/crisis’ better • know where to go to get timely help – for example to manage long term conditions People Keeping Well The PKW Team 1. PKW Community Partnerships • voluntary community organisations Emma Dickinson • Health Trainers and community wellbeing activities Sign up Commissioning Manager • Make a referral: www.sheffielddirectory.org.uk/pkw to our Zania Stevens PKW Commissioning Officer 2. Community Support Workers Weekly (Prevention) Email • approx 19 Council staff Lee Teasdale-Smith Update • co-located in GP practices Commissioning Officer • Make a referral: www.sheffield.gov.uk/csw (Carers) Zahira Begum Making Every Contact Count (MECC) Assistant Commissioning Officer People Keeping Well follows the principles of MECC – using the David Price thousands of day-to-day interactions that organisations and Assistant Commissioning individuals have with other people every day to: Officer • Hold opportunistic healthy lifestyle conversations • Support people in making positive changes to their physical Contact us: and mental health and wellbeing [email protected] Page 79 1 PKW Community Partnerships groups, libraries, local forums, Councillors, neighbourhood Police Officers, transport People Keeping Well is sometimes known as services, housing associations, TARAS, faith Social Prescribing or community referral. -

Sheffield Development Framework Core Strategy Adopted March 2009

6088 Core Strategy Cover:A4 Cover & Back Spread 6/3/09 16:04 Page 1 Sheffield Development Framework Core Strategy Adopted March 2009 Sheffield Core Strategy Sheffield Development Framework Core Strategy Adopted by the City Council on 4th March 2009 Development Services Sheffield City Council Howden House 1 Union Street Sheffield S1 2SH Sheffield City Council Sheffield Core Strategy Core Strategy Availability of this document This document is available on the Council’s website at www.sheffield.gov.uk/sdf If you would like a copy of this document in large print, audio format ,Braille, on computer disk, or in a language other than English,please contact us for this to be arranged: l telephone (0114) 205 3075, or l e-mail [email protected], or l write to: SDF Team Development Services Sheffield City Council Howden House 1 Union Street Sheffield S1 2SH Sheffield Core Strategy INTRODUCTION Chapter 1 Introduction to the Core Strategy 1 What is the Sheffield Development Framework about? 1 What is the Core Strategy? 1 PART 1: CONTEXT, VISION, OBJECTIVES AND SPATIAL STRATEGY Chapter 2 Context and Challenges 5 Sheffield: the story so far 5 Challenges for the Future 6 Other Strategies 9 Chapter 3 Vision and Objectives 13 The Spatial Vision 13 SDF Objectives 14 Chapter 4 Spatial Strategy 23 Introduction 23 Spatial Strategy 23 Overall Settlement Pattern 24 The City Centre 24 The Lower and Upper Don Valley 25 Other Employment Areas in the Main Urban Area 26 Housing Areas 26 Outer Areas 27 Green Corridors and Countryside 27 Transport Routes 28 PART