Becoming a Non-Executive Chair Boards Around the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Home Staging Catalog

2015 HOME STAGING CATALOG 888.AFR.RENT | WWW.RENTFURNITURE.COM | SINCE 1975 SOFAS 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1 ANEW ARMLESS SOFA 7 JACKSON SOFA 76”L x 32”D x 35”H 92”W x 40”D x 36”H 2 BURNISH SOFA 8 LUCKY STAR SOFA 90”L x 40”D x 40”H 91”L x 40”D x 41”H 3 COLE SOFA 9 LUMINOUS SOFA 76”L x 34”D x 33.5”H 83”L x 35”D x 33”H 4 EMMANUEL COBBLESTONE SOFA 10 MARSELLE SOFA 83”L X 35”D X 33”H 85”L x 34”D x 30”H 5 GRACELAND SOFA 11 OMEGA SOFA 80”L x 35”D x 33”H 75”L x 35”D x 34”H 6 HATHAWAY SOFA 12 OATFIELD SECTIONAL 74.5”L x 33.5”D x 34”H Armless Loveseat - 50”L x 35”D x 38”H Armless Chair - 25”L x 35”D x 38”H LAF Chair - 30”L x 35”D x 38”H RAF Chair - 30”L x 35”D x 38”H Corner - 30”L x 35”D x 38”H 2 TO PLACE AN ORDER, VISIT RENTFURNITURE.COM OR CALL 888.AFR.RENT SOFAS 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 POLO GREY SOFA 7 TORREY SOFA 77”L x 37”D x 34”H 83”L x 34”D x 30.5”H 2 POLO TAN SOFA 8 WHISPER SOFA 77”L x 37”D x 34”H 87”L x 37”D x 35”H 3 ROCKFORD SOFA WITH CHAISE 9 ZARINE SOFA 107”L x 67”D x 35”H 79”L x 36”D x 33”H 4 SAVANNA SOFA 76”L x 35”D x 38”H 5 SAVANNA SOFA WITH CHAISE 80”L x 37”D/61”D x 38”H 6 SEVILLE SOFA 75”L x 35”D x 34”H TO PLACE AN ORDER, VISIT RENTFURNITURE.COM OR CALL 888.AFR.RENT 3 1 SEVILLE SOFA (pg 3) 5 RIVER LOFT END TABLE (pg 33) 2 SEVILLE CHAIR (pg 10) 6 RIVER LOFT SOFA TABLE (pg 33) 3 SEVILLE ACCENT CHAIR (pg 10) 4 RIVER LOFT COCKTAIL TABLE (pg 33) 3 1 5 4 2 1 ZARINE SOFA (pg 3) 2 ZARINE LOVESEAT (pg 5) 3 ZARINE ACCENT CHAIR (pg 11) 4 WALDEN COCKTAIL TABLE (pg 34) 5 WALDEN END TABLE (pg 34) 1 5 4 2 3 LOVESEATS 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 EMMANUEL -

The Dining Room

the Dining Room Celebrate being together in the room that is the heart of what home is about. Create a space that welcomes you and your guest and makes each moment a special occasion. HOOKER® FURNITURE contents 4 47 the 2 Adagio 4 Affinity New! dining room 7 American Life - Roslyn County New! Celebrate being together with dining room furniture from Hooker. Whether it’s a routine meal for two “on the go” 12 American Life - Urban Elevation New! between activities and appointments, or a lingering holiday 15 Arabella feast for a houseful of guests, our dining room collections will 19 Archivist enrich every occasion. 23 Auberose From expandable refectory tables to fliptop tables, we have 28 Bohéme New! a dining solution to meet your needs. From 18th Century European to French Country to Contemporary, our style 32 Chatelet selection is vast and varied. Design details like exquisite 35 Corsica veneer work, shaped fronts, turned legs and planked tops will 39 Curata lift your spirits and impress your guests. 42 Elixir Just as we give careful attention to our design details, we 44 Hill Country also give thought to added function in our dining pieces. Your meal preparation and serving will be easier as you take 50 Leesburg advantage of our wine bottle racks, flatware storage drawers 52 Live Edge and expandable tops. 54 Mélange With our functional and stylish dining room selections, we’ll 56 Pacifica New! help you elevate meal times to memorable experiences. 58 Palisade 64 Sanctuary 61 Rhapsody 72 Sandcastle 76 Skyline 28 79 Solana 82 Sorella 7 83 Studio 7H 86 Sunset Point 90 Transcend 92 Treviso 95 True Vintage 98 Tynecastle 101 Vintage West 104 Wakefield 106 Waverly Place 107 Dining Tables 109 Dining Tables with Added Function 112 Bars & Entertaining 116 Dining Chairs 124 Barstools & Counter Stools 7 132 Index & Additional Information 12 1 ADAGIO For more information on Adagio items, please see index on page 132. -

Chair / Sofa 3

1 Trace Side Table 2 Fiji Chair 3 Fiji 2 Seat Sofa 4 Trace Side Table 5 Trace Coffee Table Fiji Seating designed by naughtone 2017 6 Fiji 3 Seat Sofa About Fiji As naughtone’s most luxuriously upholstered lounge chair and sofa, the Fiji range offers a significantly different aesthetic to other naughtone lounge chairs, fiji as the plush upholstery provides a welcoming 6 cocoon-esque retreat. The hidden swivel on Fiji chair makes it ideal for a multitude of situations. Chair / Sofa 3 4 5 Compliance • SCS Indoor Advantage™ Gold Certificate • FSC®certified products available upon request • naughtone is FISP and ISO14001 certified • Our seating is designed to meet or exceed all EN performance requirements per BS EN 16139:2013 1 2 Sizes All dimensions quoted are rounded to the nearest 5mm or nearest 1/2 inch Other Options FIJICH FIJICHBSW Fiji Chair Fiji Chair with Swivel Two Tone mm W 850 D 865 H 885 Seat 470 mm W 850 D 865 H 885 Seat 470 Outer / Inner and Seat Cushion inch W 33.5 D 34 H 35 Seat 18.5 inch W 33.5 D 34 H 35 Seat 18.5 FIJI2SF FIJI3SF Fiji 2 seat sofa Fiji 3 seat sofa mm W 1650 D 865 H 885 Seat 470 mm W 2250 D 865 H 885 Seat 470 inch W 65 D 34 H 35 Seat 18.5 inch W 88.5 D 34 H 35 Seat 18.5 Images Resources All images shown here and many others can be downloaded from the website 3D visualisation models, 2D DWG and Revit files are available for all naughtone products www.naughtone.com or please request a link to our Dropbox account Download the files from our website www.naughtone.com 1 Fiji Chair Fiji Seating designed by naughtone -

White Oak Adirondack Chair & Ottoman (OW-3006/DC) Assembly

White Oak Adirondack Chair & Ottoman (OW-3006/DC) Assembly Instructions PARTS: A1 Left arm support 1 PC F 1 3/4” Bolt 8 PCS A2 Right arm support 1 PC B Backrest 1 PC G Allen wrench 1 PC C Seat 1 PC NOTE : 1. Please read this instruction sheet carefully before assembly. 2. Please do not tighten the bolts until all bolts are in the correct position as shown in the diagram. 3. Please unpack, lay parts and assemble on clean flat soft surface to avoid marring wood. G 1 2 A2 A1 F G C F C 3 G 4 F C B F 1/3 White Oak Adirondack Chair & Ottoman (OW-3006/DC) Assembly Instructions PARTS: D Ottoman 1 PC F 1 3/4” Bolt 4 PCS E1 Right leg frame 1 PC Left leg frame G E2 1 PC Allen wrench 1 PC NOTE : 1. Please read this instruction sheet carefully before assembly. 2. Please do not tighten the bolts until all bolts are in the correct position as shown in the diagram. 3. Please unpack, lay parts and assemble on clean flat soft surface to avoid marring wood. 1 2 E1 D G F E2 F G 2/3 White Oak Adirondack Chair & Ottoman (OW-3006/DC) Dear Customer: Please carefully check the parts. If you find a defective part, please contact us at Tel: 1-866-782-6688 or email us at [email protected]. Care Instructions Care Suggestions & Recommendations: Oak wood is a living material that continues to respond to climate condition even after being made into a piece of furniture. -

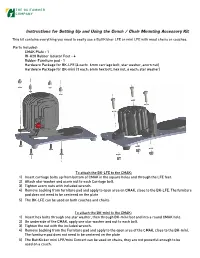

Instructions for Setting up and Using the Couch / Chair Mounting Access Ory Kit

THE GUITAMMER COMPANY Instructions for Setting Up and Using the Couch / Chair Mounting Access ory Kit This kit contains everything you need to easily use a ButtKicker LFE or mini LFE with most chairs or couches. Parts included: CMAK Plate - 1 RI-K28 Rubber Isolator Feet - 4 Rubber Furniture pad - 1 Hardware Package for BK-LFE (4 each: 6mm carriage bolt, star washer, acorn nut) Hardware Package for BK-mini (3 each: 6mm hex bolt, hex nut, 6 each: star washer) To attach the BK-LFE to the CMAK: 1) Insert carriage bolts up from bottom of CMAK in the square holes and through the LFE feet. 2) Attach star washer and acorn nut to each Carriage bolt. 3) Tighten acorn nuts with included wrench. 4) Remove backing from furniture pad and apply to open area on CMAK, close to the BK-LFE. The furniture pad does not need to be centered on the plate 5) The BK-LFE can be used on both couches and chairs. To attach the BK-mini to the CMAK: 1) Insert hex bolts through one star washer, then through BK-mini foot and into a round CMAK hole. 2) On underside of the CMAK, apply one star washer and nut to each bolt. 3) Tighten the nut with the included wrench. 4) Remove backing from the Furniture pad and apply to the open area of the CMAK, close to the BK-mini. The furniture pad does not need to be centered on the plate 5) The ButtKicker mini LFE/mini Concert can be used on chairs, they are not powerful enough to be used on a couch. -

Revolving Windsor Chair

16 Revolving Windsor Chair A few years ago it fell to me to write a story about Thomas Jefferson in a chess match with his slave Jupiter. This venture led to a play on the same subject, as well as research into the physical objects used as metaphorical vehicles for the ideas. In this regard, Jefferson makes it easy for us. One of the more obvious physical items is the revolving Windsor chair used by Jefferson when he was working to draft the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Having seen a picture of the chair in its surviving form and an- other picture of a re-creation of it, I undertook to make a similar one to use on stage. My version differs from the original in the use of a steam-bent arm rail rather than a sawn and carved one, because I could make a bent arm faster than a sawn one. Making this swivel Windsor is in some ways easier than making a normal one, in that the seat is circular rather than a sculpted outline. There are a lot of parts and processes to a Windsor chair, but with the exception of hollowing the seat, you have already seen how to do them all. Windsor chairs, as the name suggests, are of English design. Windsor chair-making in England centered around the town of High Wycombe, but the chairmaking did not begin in town. Out in the woods, workers called chair bodgers felled, split, and turned the beech legs on their springpole lathes, then sold these legs to chairmakers in town. -

Finishes & Options

FINISHES & OPTIONS WOOD STAINS, METAL PAINTS, TABLE TOP OPTIONS & DESIGN DETAILS. WOODS, COLORS AND FINISHES... WOODS Wood is an organic material that undeniably adds warmth to any space. Unlike man made materials, wood is a naturally renewable resource that poses no threat to human health during processing. Each species of wood has a unique and naturally occurring pattern that can vary greatly. Due to the complex structure of wood, small knots, piths, pores, rings, etc. may appear and add decorative appeal. Wood grain - Maple Knots Mirrors WOOD COLOR & SPECIES Each species of wood has an innate base color, ranging from white to pinkish, yellow to brown. This impacts the way that stains and paints appear when applied. We primarily work with Beech for our chairs and Ma- ple for table tops. Each of our standard wood stains have been color matched so that any standard color will appear the same in both species. We have the capabilities to source Ash, American Walnut, Oak, etc. and request that for any custom color match, special finish or non-standard species, a reference sample be provided and approved prior to production. STANDARD WOOD STAINS ( “*” implies that finish is also available on Bentwood Collection) Nautral* Parchment White* Black* Aspen Driftwood Kona* Storm Canyon* Beetroot* Dune* Nutmeg* Acorn Cocoa Honey* Almond Due to the limitations of even the most sophisticated printing process, the colors represented here are only as accurate as photography and printing allows. METAL FINISHES... STEEL & ALUMINUM Designed to be strong and durable, metal chairs can be gorgeous, too. We hand-tailor, cope and braze all joints to add even more stability, exceeding strength and durability standards, and customer expectations. -

SALSA® – Compact and Functional Treatment Chair Likamed Product Portfolio Introduction

SALSA® – Compact and functional treatment chair LiKAMED Product Portfolio Introduction LiKAMED LiKAMED shares more than 25 years of successful and services from one single source, thereby partnership and expertise with Fresenius Medical Care strengthening our relationship with our customers, in the field of medical patient chairs and bed chairs providing them with solutions and creating value. and is one of the leading providers of dialysis chairs in Europe and abroad. Both companies share a com- LiKAMED company certifications mon vision of offering innovative products to improve LiKAMED products are manufactured in Germany, the patient’s quality of life. Products from LiKAMED tested according to applicable norms and, additionally, fulfill the highest standards in terms of patient carrying TÜV product test mark. Through years of comfort, ergonomics, functionality and user safety. experience and rigorous quality controls, we stand together for highest quality „Made in Germany“. The medical patient chairs and bed chairs from LiKAMED have a strong international position in our LiKAMED is certified NephroCare and customer clinics and are fully • QM-certification according to ISO 9001 integrated into our Fresenius Medical Care logistics • QM- certification according to EN ISO 13485 and technical service processes. LiKAMED products, • Certified Environmental Management System with the associated technical service, allow Fresenius according to EN ISO 14001 Medical Care to offer a better range of products Our partner: LiKAMED GmbH For the past 40 years, LiKAMED has been highly developed, tested, manufactured and assembled successful in the medical sector. The formula by LiKAMED in-house specialists and are certified for success: design and quality. The idea: Using according to the applicable ISO management this formula and many years of experience to systems. -

Selecting Wood Furniture

Smart Shopping for Home Furnishings Selecting Wood Furniture Dr. Leona Hawks Home Furnishings & Housing Specialist 1987 HI 12 Shopping for wood furniture? Selecting high-quality wood chairs and benches can be baffling. There are many different styles, materials, and construction techniques from which you can select. To make a good selection, obtain as much information as possible. These questions should help you make a good decision. WHAT’S ON THE MARKET? WHAT’S QUALITY CONSTRUCTION? WHAT’S A QUALITY FINISH? WHAT’S ON THE LABEL? WHAT’S ON THE WARRANTY? WHAT’S ON THE MARKET? Wood is one of the most popular materials used to make chairs and benches because of its rich appearance, durability, and ease of construction. Wood furniture can be divided into solid and veneer (see Figure 12.1, Wood Construction). Most chairs are made of solid wood. You may, however, find chair backs and aprons made out of veneer plywood. Plywood is used for strength and to eliminate warpage, splitting, expansion, and contraction. All woods can be divided into deciduous and coniferous. There is some relationship between the hardness of the wood and the type of tree the wood comes from. In most cases deciduous trees consist of harder wood than coniferous trees, but not always. Deciduous simply refers to all leaf bearing trees such as Figure 12.1. Wood Construction teak, walnut, oak, maple, mahogany, cherry, and birch. Coniferous refers to cone-bearing trees such as pine, fir, redwood, and cedar. Most high- quality wooden furniture is made of deciduous trees. Generally, wood from coniferous trees are used for the less expensive furniture. -

2011-2012 Moulding Selection Guide

$5 Inspired People • Innovative Solutions • Beautiful Homes 2011-2012 Moulding Selection Guide www.mouldingandmillwork.com Quality making interiors spectacular At Moulding & Millwork Manufacturing every run of mouldings is tested for compliance with our rigid dimensional specification and quality standards. Using a computer-generated template, we verify that the height, depth and face profile of all manufactured product remains true to the original design. Moulding & Millwork has built a reputation for standards that are the highest in the industry. Outstanding Versatility Moulding & Millwork Manufacturing can instantly ship a wide variety of standard moulding profiles, or draw from our extensive library of over 5000 different shapes. Alternately, we can custom design to the exact specifications, including species, grade, and length structure, packaging, shipping, UPC coding, precision and trimming, priming, and pre-finishing. Manufacturing Technology Moulding & Millwork Manufacturing boasts some of the most advanced manufacturing equipment and processes available today, including full in-house CAD capability. This allows us to design profiles and produce them to extremely tight tolerances. Using superior technology and equipment our well-trained workforce consistently produces high quality mouldings. Optimal Utilization As responsible stewards of the forest resource Moulding & Millwork Manufacturing understands and accepts our obligation to optimize our use of raw material. We use variable width, multiple ripsaws to maximize the yield from each board. Our resaws use ultra thin blades to minimize saw kerf. Material that does not meet our length criteria is manufactured into fingerjoint blocks, glued together into fingerjoint blanks and subsequently manufactured into fingerjoint mouldings. Canadian Divisions U.S. - Rocky Mountains U.S. - Pacific Northwest U.S. -

The Craftsmanship of Philadelphia Windsor Chairmaker Joseph Henzey

The Craftsmanship of Philadelphia Windsor Chairmaker Joseph Henzey Herb Lapp Philadelphia became the Windsor chair capital of the I believe a principal motivation may have been the Colonies and took the British design to new heights making craftsmanship of this elegant 18th century chair and it a truly American furniture form. The very best of those Rose’s pride in owning it. In all likelihood, the artist Windsor chairmakers includes Joseph Henzey who helped and his subject would have discussed these objects define the American Windsor style. Many examples of his and what they meant to Rose. work can fortunately be seen and studied today. This article Rose certainly recognized quality artifacts as he looks at several of his early chairs and describes a data was an excellent craftsman himself. The valued analysis model used as an aid in determining craftsmanship, possessions surrounding Rose include musical attempts to identify specific chairmakers based upon study instruments he himself made. Rose became known and measurements, and identifies what made Henzey’s work for his beautiful tall clocks, several of which are in unique and his craftsmanship a signature of the Philadelphia the collection of the Historical Society of Berks Windsor style. County, PA (HSBC). Of financial means and a patron of the arts, Rose would have sought out aintings can sometimes provide more than and been able to afford a master chairmaker from just aesthetic enjoyment. They also serve Philadelphia, just 50 miles southeast of his native Pas windows into history, allowing us to Reading. Can we determine who that chairmaker see the past before the advent of photography. -

Complimentary Woodworking Plan

COMPLIMENTARY WOODWORKING PLAN CLASSIC ADIRONDACK CHAIR PLAN This downloadable plan is copyrighted. Please do not share or redistribute this plan in any way. It has been paid for on your behalf by JET Tools, a division of WMH Tool Group. Classic Adirondack D. Roy Woodcraftidea s in wo od Chair Plans Denis Roy 2003 Features: Supreme Comfort Elegant Appearance Contoured Seat & Back Rigid Construction Folds to 10" height Simple Construction Tools Needed: -Jig Saw -Drill -Belt Sander (recommended) -Table Saw (recommended) -Basic Hand Tools Included in Plan: Grid Diagram detailing contoured parts Parts List Cutting Diagrams 3D Assembly Diagrams Step by Step Instructions Footrest Plan Included . Classic Adirondack Chair D. Roy Woodcraft ideas in wood Denis Roy 2003 Materials List QTY Length Material Description 2 10' 2 X 4 Cedar 1 7' 2 x 6 Cedar 4 6' 1 X 6 Cedar fence boards 1 5' 1 X 8 Cedar 50 1 1/2" brass Deck screws 32 3" brass Deck screws Parts List All measurements in inches Part # Dimensions QTY Description Notes #1 38 1/2 x 5 1/4 x 1 1/2 2 Sides Cut to shape per template #2 20 x 3 1/2 x 1 1/2 1 bottom back brace Cut from 2 X 4 #3 2 1/2 x 20 7 Seat slats rip from 1 X 6 #4 18 3/8 x 3 1/2 x 1 1/2 1 top back brace Cut to shape per template #5 24 1/4 x 2 x 4 2 back legs Cut from 2 X 4 #6 21 1/2 x 2 x 4 2 front legs Cut from 2 X 4 per template #7 3 1/2 x 3 1/2 x 1 1/2 2 front angle blocks Cut from 2 X 4 #8 3 1/2 x 1 1/2 x 1 1/2 2 rear angle blocks Cut from 2 X 4 #9 31 1/2 x 7 1/4 x 3/4 2 arms Cut from 1 x 8 #10 tapered as per step 7 1 centre slat Cut pairs from 32 x 4 x 3/4 #11 2 2nd slat #12 2 3rd slat #13 2 4th slat #14 3 x 20 x 3/4 1 rear seat slat cut to shape per template cut from leftover 2 x 4 or 2 #15 14 1/4 x 2 x 4 2 footstool side x 6 #16 12 3/4 x 2 x 4 4 footstool legs cut from leftover 2 x 4 #17 2 1/2 x 20 x 3/4 7 footstool slats rip from 1 x 6 Classic Adirondack Chair D.