BILINGUALISM in PUBLIC SERVICE of CANADA Report of the Standing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Precinct Lighting Protocol (2019)

Federal Land Use, Design, and Transaction Public Approval Submission No. 2020-P45 To Board of Directors For DECISION Date 2020-04-23 Subject/Title Parliamentary Precinct Exterior Lighting Master Plan Purpose of the Submission To obtain approval of the Board of Directors for the Parliamentary Precinct Exterior Lighting Master Plan. Recommendation • THAT the Parliamentary Precinct Exterior Lighting Master Plan (ELMP) be approved subject to the following condition: o That the subsequent implementation projects for architectural and landscape lighting planned for in the ELMP be submitted to the NCC for review and approval; and • THAT the preparation and signature of the federal approval document for the Parliamentary Precinct Exterior Lighting Master Plan be delegated to the Vice President, Capital Planning Branch. Submitted by: Pierre Vaillancourt, A/Vice President, Capital Planning Branch______ Name _______________________________________________________ Signature Submission: 2020-P45 Page 1 of 5 Federal Land Use, Design, and Transaction Public Approval Submission 1. Authority National Capital Act, sections 11 and 12 2. Project Description • The Parliamentary Precinct is the home of Canada’s parliamentary system and the physical expression of our commitment to democracy and the principle of freedom. The picturesque landscape and architectural style of the Precinct are enduring visual symbols of our country, while the openness, accessibility and security of the public spaces are representative of the values treasured and celebrated by all Canadians. The Precinct provides the setting for the work of Parliamentarians and staff in a secure and efficient manner, but it is also the preeminent gathering place for public expression and celebration, as well as a place of quiet reflection. -

The Evolution of Modelling Practices on Canada's

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-2/W11, 2019 GEORES 2019 – 2nd International Conference of Geomatics and Restoration, 8–10 May 2019, Milan, Italy THE EVOLUTION OF MODELLING PRACTICES O N CANADA’S PARLIAMENT HILL:AN ANALYSIS OF THREE SIGNIFICANT HERITAGE BUILDING INFORMATION MODELS (HBIM) L. Chow 1, K. Graham 1, T. Grunt 1, M.Gallant1, J. Rafeiro,1 S. Fai 1 * 1 Carleton Immersive Media Studio (CIMS), Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada - (lchow, kgraham, tgrunt, mgallant, jraferio, sfai)@cims.carleton.ca KEY WORDS: Heritage Building Information Model, Level of Detail, Model Tolerance, Level of Accuracy, Data management ABSTRACT: In this paper, we explore the evolution of modelling practices used to develop three significant Heritage Building Information Models (HBIM) on Canada’s Parliament Hill National Historic Site — West Block, Centre Block, and The Library of Parliament. The unique scope, objective, and timeline for each model required an in-depth analysis to select the appropriate classification for Level of Detail (LOD) and Level of Accuracy (LOA). With each project, the refinement of modelling practices and workflows evolved, culminating in one of our most complex and challenging projects — the Library of Parliament BIM. The purpose of this paper is to share ideas and lessons learned for the intricate challenges that emerge when using LOD and LOA classifications including trade-offs between model performance, tolerances, and anticipated BIM use. In addition, we will evaluate how these decisions effected managing the digitization, data processing, data synthesis, and visualisation of the models. 1. OVERVIEW monument. As both the political and symbolic locus of Canada’s parliamentary democracy, the site is in every sense a stage where In 2012, Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) and Canada’s nationhood is played out for national and international the Carleton Immersive Media Studio (CIMS) began a research audiences. -

E-Democracy and E-Government: How Will These Affect Libraries?

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 472 848 IR 058 555 AUTHOR Pare, Richard TITLE E-Democracy and E-Government: How Will These Affect Libraries? PUB DATE 2002-08-00 NOTE 7p.; In: Libraries for Life: Democracy, Diversity, Delivery. IFLA Council and General Conference: Conference Programme and Proceedings (68th, Glasgow, Scotland, August 18-24, 2002); see IR 058 549. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.ifla.org. PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Access to Information; Electronic Libraries; Federal Government; *Federal Programs; Foreign Countries; *Government Libraries; Information Sources; *Internet; *Library Role; *Online Systems IDENTIFIERS *Canada; *Parliamentary Libraries ABSTRACT In the late 1980s, when few Canadian citizens had Internet access, federal departments and agencies in Canada were already preparing for the future by putting information and documentation online. This paper outlines several government-sponsored programs--SchoolNet, the Canadian Investment. Fund, Community Access Program, Canada Foundation for Innovation, VolNet, and the Smart Communities Program--that have ensured that Canadians, their communities, their libraries and their schools have quick access to the Internet. Discussion then moves to efforts to promote e-democracy, including Internet sites that feature a wide variety of material to keep voters informed, email addresses for voters to contact elected officials, campaigning over the Internet, and electronic voting. The paper then focuses on the impact of e-government and e-democracy on libraries, and specifically on how e-government and e-democracy are affecting the Canadian Library of Parliament. The Intraparl internal web, site, online catalogs, electronic news monitoring service (PARLMedia), the LEGISinfo research tool, and the electronic document series known as TIPS are each described briefly, followed by projections for the future. -

Lop Collective Agreement

COLLECTIVE AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE LIBRARY OF PARLIAMENT AND THE CANADIAN ASSOCIATION OF PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYEES ANALYSTS AND RESEARCH ASSISTANTS EXPIRY DATE June 16, 2022 LIBRARY OF PARLIAMENT PAGE i CONTENTS Page **ARTICLE 1 – PURPOSE OF AGREEMENT ............................................................................................ 1 ARTICLE 2 – INTERPRETATION AND DEFINITIONS .............................................................................. 1 ARTICLE 3 – APPLICATION ....................................................................................................................... 3 ARTICLE 4 – PRECEDENCE OF LEGISLATION AND THE COLLECTIVE AGREEMENT ...................... 4 ARTICLE 5 – MANAGERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES ..................................................................................... 4 ARTICLE 6 – RECOGNITION ..................................................................................................................... 4 ARTICLE 7 – EMPLOYEE REPRESENTATIVES ....................................................................................... 5 ARTICLE 8 – TECHNICAL CHANGE .......................................................................................................... 5 ARTICLE 9 – CHECK OFF .......................................................................................................................... 5 ARTICLE 10 - INFORMATION .................................................................................................................... 6 ARTICLE 11 – PROVISION OF BULLETIN -

Annualreport 2010-2011-E.Pdf

LIBRARY OF PARLIAMENT | ANNUAL REPORT Library Contact Information Email: [email protected] Phone: 613-995-1166 Fax: 613-992-1269 Public line: 613-992-4793 Toll-free: 1-866-599-4999 Web: www.parl.gc.ca 2010–2011 ANNUAL REPORT i Contents Message from the Parliamentary Librarian 1 Vision, Mission, Strategic Outcome 4 Overview of the Library of Parliament 7 Operating Environment for 2010–2011 10 Strategic Priorities and Key Accomplishments 13 Ongoing Operations 22 Senior Management Team 27 ii LIBRARY OF PARLIAMENT 2010–2011 ANNUAL REPORT 1 Message from the Parliamentary Librarian Being associated with one of the most impressive buildings in the country can be both a blessing and a curse. I love walking into Parliament’s Library and I still marvel at how the recent restoration has returned this 135-year- old building to its former glory. U.S. President Barack Obama described the eff ect best with one word during his February 2009 tour – “Wow.” At the same time, I recognize that this view, shared by the many visitors to Parliament each year, leaves many people with the impression that the Library of Parliament is little more than a very beautiful building , a nice piece of history with little relevance in the information age. In reality, nothing could be farther from the truth. Parliamentarians need independent, authoritative and reliable information in order to represent their constituents eff ectively and hold the Government to account. Employees at the Library are proud of our history in supporting Canadian parliamentary democracy. In the past year alone we received over 71,000 requests for reference and information. -

Building Stones of Canada's Federal Parliament Buildings

Volume 28 Numbu 1 also restored the role of the geologist, with they represent. Their design and construc- the requirement to understand the tion has been the work of formative complex reactions of the building stone to architects and builders. Great pains have the environment and its neighbouring been taken to ensure that these are masonry clcments, and in the quest to significant structures, of unique design find suitable replacement stone. and beauty, using quality materials and built with exacting craftsmanship, worrhy R~UM~ of thc importance of the business that Les pierres de construction utilisk pour transpirs within thcir walls. Canada's les tdifices du Parlement h Omwa Parliament Buildings in Ottawa are no prwienncnt de nombreuses carrikres exception. autant au Canada, aux &ts-Unis que de This is the first of a series of Building Stones plusieurs pays europkns. Ells ont et4 articles about the building stones of till&, pods et sculpt& suivant des Canada's federal and provincial Parlia- of Canada's Federal procedCs precis, en conformite avec 1s ment Buildings. Historians, political Parliament Buildings r&glesde I'an de I'epoque. La rcconstruc- scientists, architects, and engineers have tion de I'Cdifice du centre qui est le sujet written at length about the buildings and D.E. Lawxnce du prCsent article, a ttt une &rc qui tbcir varied histories. Geologists, for the Geological Survey of Cad s'est Ctirk Ctant donnt les prioritCs lors de most part, have been silent. It is expected GO1 Booth Smrt la Grande Guerrc de 1914-1918. Ces that this series will be written by a Ottawa, Ontario KIA OE8 pierres de revetement des edifices du number of geologists, and may cover all [email protected] Parlement ont subi les avanies du climat, provinces and territories to document the du feu, de tremblements de terre et de la stories of the stones themselves. -

Annual Report 2 0 0 9 – 2 0 1 0

LIBRARY OF PARLIAMENT | ANNUAL REPORT 2 0 0 9 – 2 0 1 0 ANNUAL REPORT 2009–2010 i TABle OF ContentS MESSAGE FROM THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARIAN 1 Section 1: RAISON D’ÊTRE 3 SECTION 2: OVERVIEW OF THE ORGANIZATION 5 SECTION 3: OPERATING ENVIRONMENT 7 SECTION 4: STRATEGIC PRIORITIES AND KEY ACCOMPLISHMENTS FOR 2009–2010 9 SECTION 5: YEAR IN REVIEW 13 SECTION 6: SUMMARY OF RESOURCE INFORMATION 19 SENIOR Management TEAM 21 In 2009–2010, the Library remained guided by its defining vision: to be Parliament’s preferred and trusted source of information and knowledge. ANNUAL REPORT 2009–2010 1 MESSage From the Parliamentary LIBrarian The Library of Parliament’s This year also saw the negotiation of an important roots reach back to the agreement with Library and Archives Canada to digitize 1700s, in the collections historical debates of both the Senate and House of created for the legislative Commons. This will significantly increase access to libraries of Upper and parliamentary records and provide a treasure trove of Lower Canada. Since information to parliamentary clients, historians and the Confederation in 1867, research community, as well as the public. the Library has grown and These modernized Library services flow from the evolved with the nation it systematic organizational renewal project that I initiated serves and today is a modern after my appointment as Parliamentary Librarian. While organization responding to this undertaking has been challenging, it has enabled us the needs of a 21st century to focus on rebuilding our corporate infrastructure and William R. Young Parliament. restructure our research services to more effectively In 2009–2010, the Library remained guided by its defining fulfill our responsibilities to Parliament. -

Fire Infrographic

The P��������� P�������� GREAT FIRE of 1916 CANADA on Parliament Hill #SenCA February 3, 1916 The House of Commons is filled with Members of Parliament attending an evening session of Parliament. 8:55 p.m. Parliament Hill before the fire of February 3, 1916 Credit: Topley Studio Fonds / Library and Archives Canada / PA-008336 Fire starts on one of the lower shelves of a desk in the Reading Room. 8:59 p.m. First fire engine arrives on the Hill. Fire is already engulfing the roof of Centre Block. 9:00 p.m. Chief Doorkeeper of the HoC, runs into the House of Commons chamber, yelling, 9:01 p.m. “There is a big fire in the Reading Librarian Michael Connolly MacCormac Room; everybody get out quickly!” dispatches a messenger to close the Library’s iron doors, protecting the Library from fire. 9:02 p.m. Fire bursts through the doors of the Reading Room and into 9:07 p.m. the hallways surrounding the HoC. HoC Speaker Albert Sévigny runs upstairs to help his wife and young children, who are asleep in their nursery, escape to safety. 9:20 p.m. Albert Sévigny Members of the 77th Battalion, who were dining at Credit: Library and Archives Canada / PA-005103 the nearby Château Laurier, rush to Parliament to provide rescue assistance and crowd-control. 10:15 p.m. Fire spreads to the roof of the Library and sweeps towards the centre of the building. 11:30 p.m. Prime Minister Borden meets with members of his Cabinet at a suite in the Château Laurier to discuss a plan of action on how to continue parliamentary functions. -

Celebrating the 200Th Anniversary of the Ontario Legislative Library

Feature Celebrating the 200th Anniversary of the Ontario Legislative Library In its 200-year history Ontario’s Legislative Library has operated in numerous locations, survived many fires, and is currently embracing the digital age. In celebration of this significant milestone, the author briefly traces the library’s development, examines the challenges it and other legislative libraries have encountered as they fulfill their non-partisan role to support the work of parliament, and finally notes recent trends in their operations Monica Cop 2016 CanLIIDocs 247 n 2016, the Ontario Legislative Library is legal practice, and even become Mayor of Toronto. The celebrating its 200th anniversary. This occasion subsequent pioneering Librarians included William Ioffers an opportunity to reflect on the Library’s rich Winder, a medical practitioner and a member of the history and to examine the evolution of how it and “Bully Boys” guerrilla group that fought in the Niagara other legislative libraries across Canada deliver their Peninsula during the War of 1812, and Alpheus Todd, services. a man who had started working at the Library as a 15-year-old indexing prodigy. During these early The earliest incarnation of the Ontario Legislative days, the Library struggled to maintain its collection Library dates to the late 1700s in the Province of Upper numbers reportedly due to the failure of members to Canada. It began with a small book collection to assist return books, the frequent moves of the Legislature to elected officials in their jobs as legislators. However, it makeshift accommodation as a result of several fires, was on April 1, 1816 that the Library of the Province of and the resulting poor conditions in which the books Upper Canada was formally established. -

Create a Virtual Tour with the Google Tour Creator

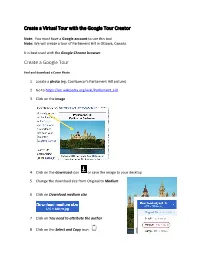

Create a Virtual Tour with the Google Tour Creator Note: You must have a Google account to use this tool. Note: We will create a tour of Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Canada. It is best used with the Google Chrome browser. Create a Google Tour Find and download a Cover Photo 1. Locate a photo (eg: Coollcaesar’s Parliament Hill picture) 2. Go to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parliament_Hill 3. Click on the image 4. Click on the download icon or save the image to your desktop 5. Change the download size from Original to Medium 6. Click on Download medium size 7. Click on You need to attribute the author 8. Click on the Select and Copy icon Create the Tour 1. Sign on to your Google Account 2. Go to the site https://vr.google.com/tourcreator 3. Click on the Get Started button 4. Click on the New Tour button 5. The editing screen appears 6. In the Title text box type Parliament Hill 7. Click in the Description text box 8. Paste the following text into this text box Parliament Hill is an area of land on the Ottawa River in Ottawa, Canada. Its Gothic revival buildings are the home of the Parliament of Canada. Parliament Hill attracts approximately 3 million visitors each year. Originally the site of a military base in the 18th century, development of the area into a governmental zone began in 1859, after Queen Victoria chose Ottawa as the capital of the Province of Canada. Following a number of extensions to the parliament and departmental buildings and a fire in 1916 that destroyed the Centre Block, Parliament Hill took on its present form with the completion of the Peace Tower in 1927. -

What the Parliament Buildings Mean to Me

What the Parliament Buildings Mean to Me by Audrey Moore Despite the cynicism many people have about politics and politicians, the buildings 2007 CanLIIDocs 311 that house our parliamentary institutions are still held with great affection in the hearts of many Canadians. This article demonstrates the fondness with which people look upon these buildings. ew people who have come to Ottawa have not seen than any other place in Canada for the permanent Seat of them. They stand in a breathtaking setting, atop the future Government of the Province and is selected by F Her Majesty accordingly.2 limestone cliffs overlooking the junction of the Rideau Canal and the Ottawa River. They are captivating By Imperial Command, this small lumber town was in every season: in the rich golds, oranges and reds of the destined for greatness. The handsome sum of $480,000 fall; when the earth is softly blanketed by winter’s snow; was made available to construct a legislative building amongst the young green leaves of spring and when the and two departmental structures to house the govern- weather is hot and hazy in our all too brief Canadian ment. From a prestigious nation wide competition, two summer. They are Gothic revival in style, they are etched groups of architects were selected – one group to design in our consciousness, they are the seat of democracy. the Centre Block (the legislative building) and the other They are Canada’s Parliament Buildings. the East and West Block (the two departmental struc- They are on my list of favourite architecture, and I rel- tures). -

Annual Report: 2018-2019

LIBRARY OF PARLIAMENT ANNUAL REPORT 2018–2019 CONTENTS Message from the Parliamentary Librarian ................................................ 1 The Library by the Numbers ........................................................................ 2 A Strategy for Keeping Clients at the Forefront .......................................... 3 Services ......................................................................................................... 7 About the Library ........................................................................................ 21 Financial Information ................................................................................. 24 Library of Parliament i Annual Report 2018–2019 MESSAGE FROM THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARIAN Since I arrived in this office in June 2018, I have had the privilege and honour of presiding over an extraordinary time of transition at the Library. And what a ride it has been. Early in 2019, Centre Block closed for renovations, which meant that the Library’s iconic Main Branch also had to close. It will be many years before these spaces reopen. The Library’s focus All of our work in 2018–2019 was rooted in the Library’s throughout 2018–2019 strategic priorities of ensuring that we remain relevant to was to manage a our clients, demonstrate agility in the face of rapid change, massive change while we and nurture a healthy workplace. continued serving clients to the highest possible As the new Parliamentary Librarian, I focused this year on standards. Did the closure getting to know