Governance in Local Government

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Property Crime Drop: a Regional Analysis

NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research Bureau Brief Issue paper no. 88 July 2013 The Great Property Crime Drop: A regional analysis Don Weatherburn and Jessie Holmes Aim: To describe and discuss regional variation between parts of NSW in the rate at which theft and robbery offences have fallen. Method: Percentage changes in rates of offending in robbery and various categories of theft were calculated for the period 2000 to 2012. Changes in the extent to which rates of crime across areas have become more similar were quantified by comparing the standard deviation in crime rates across areas in 2000 to the standard deviation in crime rates in 2012. Product moment calculations were used to measure (a) the extent to which areas with high crime rates in 2000 also had high crime rates in 2012 and (b) the extent to which areas with the highest crime rates in 2000 had the largest falls in crime in 2012. Results: The fall in property crime and robbery across NSW between 2000 and 2012 has been very uneven; being much larger in Sydney and other urban areas than in rural areas. The fall in theft offence rates ranges from 62 per cent in the Sydney Statistical Division (SD) to 5.9 per cent in the Northern SD. Similarly, the fall in robbery rates ranges from 70.8 per cent in the Sydney SD to 21.9 per cent in the Northern SD. In some areas some offences actually increased. The Murray, Northern, Murrumbidgee, North Western, Hunter and Central West SDs, for example, all experienced an increase in steal from a retail store. -

NEEDHELP ATHOME? Lane Cove, Mosman

Live in the Northern Sydney Region? NEED HELP AT HOME? Are you ... There are Commonwealth Home and Community • Aged 65+ (50+ for Aboriginal persons) Care (HACC) services and NSW Community Care • A person with a disability, or Supports Programs (CCSP) in your local area that may • A carer be able to help. Interpreting Service Deaf and hearing impaired Translating & Interpreting Service Telephone Typewriter Service (TTY) �����������1300 555 727 TIS ������������������������������������������������������������������������������13 14 50 Lane Cove, Mosman, North Sydney or Willoughby Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People Greek Welfare Centre ................................................................ 9516 2188 Aboriginal Access & Assessment Team ......................... 1300 797 606 CALD/Dementia Aboriginal HACC Development Officer .............................. 9847 6061 HammondCare ........................................................................... 9903 8326 Frail Aged/Dementia Community Care Northern Beaches Ltd ............................ 9979 7677 LNS Multicultural Aged Day Care Program ....................... 9777 7992 Aged Care Assessment Team (ACAT) CALD Assessment for community aged care services and residential care St. Catherine’s Aged Care Services ....................................... 8875 0919 Royal North Shore Hospital .................................................... 9462 9333 Dementia UnitingCare Ageing ������������������������������������������������������������� 1800 486 484 Allied Health Frail Aged/Dementia -

Northern Sydney District Data Profile Sydney, South Eastern Sydney, Northern Sydney Contents

Northern Sydney District Data Profile Sydney, South Eastern Sydney, Northern Sydney Contents Introduction 4 Demographic Data 7 Population – Northern Sydney 7 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population 10 Country of birth 12 Languages spoken at home 14 Migration Stream 17 Children and Young People 18 Government schools 18 Early childhood development 28 Vulnerable children and young people 34 Contact with child protection services 37 Economic Environment 38 Education 38 Employment 40 Income 41 Socio-economic advantage and disadvantage 43 Social Environment 45 Community safety and crime 45 2 Contents Maternal Health 50 Teenage pregnancy 50 Smoking during pregnancy 51 Australian Mothers Index 52 Disability 54 Need for assistance with core activities 54 Housing 55 Households 55 Tenure types 56 Housing affordability 57 Social housing 59 3 Contents Introduction This document presents a brief data profile for the Northern Sydney district. It contains a series of tables and graphs that show the characteristics of persons, families and communities. It includes demographic, housing, child development, community safety and child protection information. Where possible, we present this information at the local government area (LGA) level. In the Northern Sydney district there are nine LGAS: • Hornsby • Hunters Hill • Ku-ring-gai • Lane Cove • Mosman • North Sydney • Northern Beaches • Ryde • Willoughby The data presented in this document is from a number of different sources, including: • Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) • Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) • NSW Health Stats • Australian Early Developmental Census (AEDC) • NSW Government administrative data. 4 Northern Sydney District Data Profile The majority of these sources are publicly available. We have provided source statements for each table and graph. -

Map 4 from NSW ASGC.Pdf

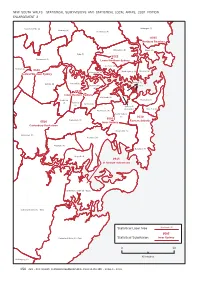

NEW SOUTH WALES—STATISTICAL SUBDIVISIONS AND STATISTICAL LOCAL AREAS, 2001 EDITION ENLARGEMENT 2 Baulkham Hills (A) Warringah (A) Hornsby (A) Ku-ring-gai (A) 05650565 NorthernNorthern BeachesBeaches Willoughby (C) Manly (A) Ryde (C) 05550555 Parramatta (C) LowerLower NorthernNorthern SydneySydney Lane Cove (A) Holroyd (C) 05400540 05400540 North Sydney (A) Mosman (A) Hunter'sHunter's HillHill (A)(A) CentralCentral WesternWestern SydneySydney SydneySydney (C)(C) -- Auburn (A) Concord (A) Drummoyne InnerInnerInnerInner (A) 05350535 InnerInnerInner WesternWesternWestern SydneySydneySydney LeichhardtLeichhardtLeichhardt (A)(A)(A) Strathfield Woollahra (A) Burwood (A) Ashfield (A) (A) Sydney (C) - Remainder Waverley (A) Marrickville (A) South Sydney (C) 05100510 05050505 Canterbury (C) EasternEastern SuburbsSuburbs 05200520 InnerInnerInner SydneySydneySydney Canterbury-BankstownCanterbury-Bankstown Botany Bay (C) Bankstown (C) Rockdale (C) Hurstville (C) Randwick (C) Kogarah (A) 05150515 StSt George-SutherlandGeorge-Sutherland (Sutherland Shire (A) - East) Sutherland Shire (A) - West Statistical Local Area Leichhardt (A) 05050505 Sutherland Shire (A) - East Statistical Subdivision InnerInnerInner SydneySydneySydney 0 10 Kilometres Wollongong (C) 156 ABS • AUSTRALIAN STANDARD GEOGRAPHICAL CLASSIFICATION • 1216.0 • 2001 NEW SOUTH WALES—STATISTICAL SUBDIVISIONS AND STATISTICAL LOCAL AREAS, 2001 EDITION ENLARGEMENTS Uralla (A) Gilgandra (A) Manilla (A) 35053505 CentralCentral MacquarieMacquarie (excl.(excl. Dubbo)Dubbo) Narromine (A) Dubbo (C) -

Local Government Responses to Urban Consolidation Policy: Meeting Housing Targets in Northern Sydney

Local Government Responses to Urban Consolidation Policy: Meeting Housing Targets in Northern Sydney THESIS PROJECT Planning and Urban Development Program The Faculty of the Built Environment University of New South Wales Lauren Baroukh 3158821 - i - ABSTRACT Urban consolidation is the central housing policy guiding future residential development in the existing urban areas of Sydney. In accordance with the Sydney Metropolitan Strategy and subsequently elaborated in various Subregional Strategies, councils are required to achieve housing targets and accommodate higher density housing within their Local Government Areas. This thesis examines how councils are implementing these targets and achieving the urban consolidation objectives defined within strategic planning documents. It provides an analysis of council responses, primarily through the rezoning of land within revised Local Environmental Plans and local housing strategies. The thesis examines the factors which councils consider when selecting sites for higher density housing, such as proximity to town centres and public transport, the capacity of existing infrastructure and services, preserving the character of low density areas and determining appropriate building heights. The research indicates that councils are beginning to implement the housing targets and achieving many of the objectives suggested within the Sydney Metropolitan Strategy. In particular, the thesis identifies the issue of infrastructure provision as requiring further consideration by councils and state agencies. Higher density housing within existing urban areas needs to be appropriately located and planned in a way that responds to the unique characteristics of the locality. - ii - ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks go to Christine Steinmetz for her valuable advice, guidance and support which is much appreciated. I would also like to thank the interviewees for their time and insights which have made a valuable contribution to this project. -

Case Study: Northern Sydney Community Recyling Centre

Case Study: Northern Sydney community recyling centre COUNCIL NAME Overview Northern Sydney Regional Organisation Five councils in northern Sydney have partnered to establish a Community Recycling Centre of Councils (NSROC) (CRC) on commercial premises. No council had available operational land suitable to establish WEB ADDRESS a facility, so Northern Sydney Regional Organisation of Councils arranged a lease of a suitable www.nsroc.com.au commercial premises. Working together has allowed resource sharing between councils, increased the efficiency of problem waste collection and helps to reduce the illegal dumping of problem wastes. Background Northern Sydney Regional Waste Strategy aims to manage problem wastes through establishing three CRCs in the region by 2021. Hornsby Shire Council is setting up a CRC at the northern end of the region. Another site was sought to cater for residents on the lower north shore. Artarmon was considered suitable as it is centrally located and the zoning permits waste facilities. Four councils were already supporting Chemical Clean Out events in conjunction with the EPA, and the events were increasing in popularity. The one council which no longer ran such events was regularly asked by residents to restore the service. The key objective of this project was to provide accessible and affordable problem waste disposal facilities for the region. Implementation A governance framework provided a transparent process which enabled the five partner councils and NSROC to work collectively to set the project objectives and oversee implementation. A Deed of Agreement was established to clarify each partner's responsibilities and roles. Signing the deed demonstrated each party's acceptance of its obligations and ensured that each partner could budget for its own resource contributions in the knowledge that the remaining funds were guaranteed. -

Sydney North Primary Health Network Integrated Mental Health Atlas

Disclaimer Inherent Limitations The Menzies Centre for Health Policy, University of Sydney and ConNetica (together the “project team”) have prepared this report at the request of Sydney North Primary Health Network in our capacity as consultants and in accordance with the terms and conditions of the MENTAL HEALTH ATLAS FOR NORTHERN SYDNEY research project agreement. The report is solely for the purpose and use of Sydney North Primary Health Network (ABN 38 605 353 884) trading as Northern Sydney PHN and has been prepared through a consultancy process using specific methods outlined in the Framework section of this report. The project team have relied upon the information obtained through the consultancy as being accurate with every reasonable effort made to obtain information from all mental health service providers across the region. The information, statements, statistics and commentary (together the “information”) contained in this report have been prepared by the project team from publicly available information as well as information provided by the Primary Health Network and service providers across the Northern Sydney catchment area. The project team have not undertaken any auditing or other forms of testing to verify accuracy, completeness or reasonableness of the information provided or obtained. Accordingly, whilst the information presented in this report is provided in good faith, The Menzies Centre for Health Policy, University of Sydney and ConNetica can accept no responsibility for any errors or omissions in the information provided by other parties, nor the effect of any such error on our analysis, discussion or recommendations. The language used in some of the service categories mapped in this report (e.g. -

Northern Sydney Region Home Modification & Maintenance Services

HOME MODIFICATION & MAINTENANCE HOMESERVICEHOME MODIFICATION MODIFICATION & & MAINTENANCEMAINTENANCE SERVICE SERVICE NORTHERNNorthernNORTHERN SydneySYDNEY SYDNEY Region REGION REGION NORTHERN SYDNEY REGIONHome Modification & Maintenance Services Manly WarringahManly Pittwater Warringah Pittwater Community AidCommunity Service Inc. Aid Service Inc. HOME MAINTENANCE & MODIFICATION SERVICE LOGO CYMK: LOGO PANTONE: C - 100 PANTONE 273 PC M - 96 Manly Warringah Pittwater Y - 0 K - 8 PANTONE 158 PC C - 0 M - 61 GRADIENT Community Aid Service Inc. Y - 97 K - 0 GRADIENT GRADIENT GRADIENT LOGO FLAT: EQUIVALENT IN PRINT: C - 100 PANTONE 273 PC M - 96 Y - 0 K - 8 PANTONE 158 PC C - 0 M - 61 GRADIENT Y - 97 K - 0 GRADIENT LOGO REVERSED: EQUIVALENT IN PRINT: C - 100 PANTONE 273 PC M - 96 Y - 0 K - 8 PANTONE 158 PC C - 0 M - 61 GRADIENT Y - 97 K - 0 GRADIENT LOGO FLAT BLACK & BLACK REVERSE: BLACK 100% LOGO BLACK: BLACK 95% BLACK 60% GRADIENT GRADIENT CLIENT : LANE COVE & NORTH SIDE COMMUNITY SERVICES PROUDLY DESIGNED BY PRODUCT : LOGO SPECIFICATIONS VERSION : Final FONTS DATE : 03/08/11 Lane Cove : Galatia - SIL Bold COPYRIGHT © 2010 CLEVERLINK. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FILES & : Galatia - SIL Bold 1300 721 837 LOGO FULL & ICON: North Side : Tangerine Bold www.cleverlink.com.au EPS, AI, PDF, JPEG, PNG, TIF COMMUNITY SERVICES : Galatia - SIL Regular [email protected] ALL OTHER VERSIONS: AI, EPS We care for you : Tangerine Bold Level 1 Home Modification & Maintenance Service The Level 1 Home Modification and Maintenance Service is a State and Federal government funded service which provides modifications and maintenance services to the frail aged, people with a disability (including children) or their carers to assist them to live independent- ly and safely in their own homes. -

Needs Assesment for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender (Glbt)

NEEDS ASSESMENT FOR GAY, LESBIAN, BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER (GLBT) COMMUNITIES IN THE MANLY LGA Sue Ladd Community Services Planner Manly Council January 2004 2 Table of Contents Page No. 1.0 Definition 3 2.0 Consultation Method 3 2.1 Focus group 3 2.2 Survey of GLBT and support groups 4 2.3 Service Providers 4 2.4 Literature review 4 3.0 Review of Services for GLBT 4 3.1 Northern Beaches/ Northern Sydney Services 4 3.2 Regional/ NSW-wide Services 5 3.3 Gaps 6 4.0 Consultation Results 6 4.1 Future vision 6 4.2 Summary of Issues 7 4.3 Issues, Needs & Strategies 8 5.0 Summary of Needs for GLBT 14 • Appendix A - Email survey to GL@M Members 16 • Appendix B - Survey of PFLAG members 17 PS: 0533SLTB January 2004 Needs Assessment for GLBT 3 1.0 DEFINITION Sexual and gender diversity in our community relates to gay men, lesbians, bisexuals and transgender people. Following a recommendation from Manly’s Social Plan Implementation Committee, Manly Council resolved to include gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender communities in the planning process for the 2004 Manly Social Plan. This follows an increasing trend by several NSW councils to be inclusive of this group. Gay men and lesbians are also designated as an optional target group by the Department of Local Government for social planning. For Manly Council, it is increasingly relevant to include the needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender, to ensure consistency with the NSW Anti-Discrimination Act (1977) which makes discrimination, harassment or vilification on the grounds of sexuality, transgender and HIV/AIDS status illegal. -

Sport and Recreation in North Sydney

Recreation Facilities and Programs Sports Fields Community Centres North Sydney Council maintains and manages a wide The local Community Centres offer a range of range of local sports fields. Many have timed lights to recreational activities. Pick up the Community Centres allow for their use at night. The fields operate on a user- Sport and in North Sydney brochure in Customer Service or pays system, levying fees on local schools, organisations Stanton Library or see the website for further details: and sporting groups who wish to hire sports fields www.northsydney.nsw.gov.au/communitycentres exclusively for the purpose of organised sport. Recreation in Parks and Playgrounds Sports Fields available for Hire There are a wide range of parks and playgrounds in the ANDERSON PARK, Clark Rd, Neutral Bay - Football and cricket North Sydney area ranging from children’s playgrounds CAMMERAY PARK, Between Ernest St, Park Ave & North Sydney to preserved bush land. For further details visit: Cammeray Rd, Cammeray - Golf Course, football & cricket www.northsydney.nsw.gov.au/parks field, tennis courts Recreation Programs & Events FORSYTH PARK, Montpellier St, Neutral Bay - Hockey, Council and Community groups hold a number cricket, Scout Hall programs and events throughout the year. Go to PRIMROSE PARK, Young St, Cammeray - tennis courts, ‘What’s On’ on the home page of Council’s website: football, hockey, cricket fields www.northsydney.nsw.gov.au or for Arts and Culture ST LEONARDS PARK & NORTH SYDNEY OVAL 1 & 2, events: www.northsydney.nsw.gov.au/artsandcultureevents Cnr Miller St & Ridge St, North Sydney - No.1 Oval has been Walking in North Sydney used as a cricket and football grounds for over 100 yrs. -

Northern Beaches LGA Fact Sheet

NORTHERN BEACHES LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA HEALTH PROFILE Northern Beaches Local Government Area (LGA) is one of 9 LGAs in the Sydney North Health Network (SNHN) region. Northern Beaches LGA was formed in May 2016 through the merger of Manly, Pittwater and Warringah LGAs. Key Areas: Childhood immunisation rates, obesity and risky alcohol consumption Northern Beaches LGA is an affluent area ranking in the least disadvantaged quintile (20%) on the index HEALTH DRIVERS of relative socio-economic disadvantage. There is a small area of comparatively high socio-economic disadvantage in the suburbs of Narraweena, Narrabeen, Brookvale and Allambie Heights. 1.3% of people 34.1% of people aged 23.1% of low-income aged 16-64 years receive 17 years participating in families experience financial unemployment benefits tertiary education stress from mortgage or rent SNHN: 1.3%; NSW: 4.5% SNHN: 41.3%; NSW: 28.9% SNHN: 28.8%; NSW: 29.3% VULNERABLE GROUPS Older People Disability Children 16.6% (44,947) of the total population aged 65+ years 3.7% of 5.3% SNHN: 15.8%; NSW: 16.1% the population (2,925) have severe Between 2021-2041, there of children in or profound low-income, welfare- will be an increase of 51.1% disability recipient families in the 65+ years population SNHN: 3.7%; SNHN: 5.3%; NSW: 20.6% SNHN: 53.7%; NSW: 58.9% NSW: 5.4% HEALTH RISK FACTORS Alcohol Smoking Obesity 21.2 per 100 8.9 per 100 21.7 per 100 (18+ years) engaging in (18+ years) current (18+ years) obese high risk drinking smokers SNHN: 20.1; NSW: 30.9 SNHN: 16.6; NSW: 15.5 SNHN: 7.9; NSW: 14.4 CHILDHOOD IMMUNISATION CANCER SCREENING IMMUNISATION RATES LOWER THAN THE Bowel cancer screening participation rates NATIONAL ASPIRATIONAL TARGET OF 95% among people aged 50-74 years in Manly (45.0%), Pittwater (44.8%) and Warringah (43.5%) are higher than both SNHN (42.1%) and NSW (39.5%) rates. -

Report on Northern Beaches Suicide Postvention/Prevention Protocol Pilot

Dr. Grenville Rose Centre for Social Research in Health Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences John Goodsell Building UNSW Sydney NSW 2052 Tel: 9385 6776 Email: [email protected] Report on Northern Beaches Suicide Postvention/Prevention Protocol Pilot. Table of Contents Prologue ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Executive Summary-Community Care Northern Beaches .............................................................. 2 Overall Summary ........................................................................................................................... 3 Summary of interview and data results: .......................................................................................... 3 Summary of Positives ................................................................................................................. 3 Areas of improvement................................................................................................................. 4 Background .................................................................................................................................... 5 Quantitative findings: ...................................................................................................................... 8 Methods ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Results. ..................................................................................................................................