Mafb Lineage Tracing to Distinguish Macrophages from Other Immune

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loss of Mafb and Maf Distorts Myeloid Cell Ratios and Disrupts Fetal Mouse Testis Vascularization and Organogenesisǂ

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.26.441488; this version posted April 26, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Loss of Mafb and Maf distorts myeloid cell ratios and disrupts fetal mouse testis vascularization and organogenesisǂ 5 Shu-Yun Li1,5, Xiaowei Gu1,5, Anna Heinrich1, Emily G. Hurley1,2,3, Blanche Capel4, and Tony DeFalco1,2* 1Division of Reproductive Sciences, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, 10 OH 45229, USA 2Department of Pediatrics, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH 45267 USA 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH 45267 USA 15 4Department of Cell Biology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710 USA 5These authors contributed equally to this work. ǂThis work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R37HD039963 to BC, R35GM119458 to TD, R01HD094698 to TD, F32HD058433 to TD); March of Dimes (1-FY10- 355 to BC, Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Award 5-FY14-32 to TD); Lalor Foundation 20 (postdoctoral fellowship to SL); and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (Research Innovation and Pilot funding, Trustee Award, and developmental funds to TD). *Corresponding Author: Tony DeFalco E-mail: [email protected] 25 Address: Division of Reproductive Sciences Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center 3333 Burnet Avenue, MLC 7045 Cincinnati, OH 45229 USA Phone: +1-513-803-3988 30 Fax: +1-513-803-1160 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.26.441488; this version posted April 26, 2021. -

RBP-J Signaling − Cells Through Notch Novel IRF8-Controlled

Sca-1+Lin−CD117− Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells Induce the Generation of Novel IRF8-Controlled Regulatory Dendritic Cells through Notch −RBP-J Signaling This information is current as of September 25, 2021. Xingxia Liu, Shaoda Ren, Chaozhuo Ge, Kai Cheng, Martin Zenke, Armand Keating and Robert C. H. Zhao J Immunol 2015; 194:4298-4308; Prepublished online 30 March 2015; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402641 Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/content/194/9/4298 Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2015/03/28/jimmunol.140264 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Material 1.DCSupplemental References This article cites 59 articles, 19 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/194/9/4298.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision by guest on September 25, 2021 • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2015 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology Sca-1+Lin2CD1172 Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells Induce the Generation of Novel IRF8-Controlled Regulatory Dendritic Cells through Notch–RBP-J Signaling Xingxia Liu,*,1 Shaoda Ren,*,1 Chaozhuo Ge,* Kai Cheng,* Martin Zenke,† Armand Keating,‡,x and Robert C. -

Prox1regulates the Subtype-Specific Development of Caudal Ganglionic

The Journal of Neuroscience, September 16, 2015 • 35(37):12869–12889 • 12869 Development/Plasticity/Repair Prox1 Regulates the Subtype-Specific Development of Caudal Ganglionic Eminence-Derived GABAergic Cortical Interneurons X Goichi Miyoshi,1 Allison Young,1 Timothy Petros,1 Theofanis Karayannis,1 Melissa McKenzie Chang,1 Alfonso Lavado,2 Tomohiko Iwano,3 Miho Nakajima,4 Hiroki Taniguchi,5 Z. Josh Huang,5 XNathaniel Heintz,4 Guillermo Oliver,2 Fumio Matsuzaki,3 Robert P. Machold,1 and Gord Fishell1 1Department of Neuroscience and Physiology, NYU Neuroscience Institute, Smilow Research Center, New York University School of Medicine, New York, New York 10016, 2Department of Genetics & Tumor Cell Biology, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee 38105, 3Laboratory for Cell Asymmetry, RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, Kobe 650-0047, Japan, 4Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, GENSAT Project, The Rockefeller University, New York, New York 10065, and 5Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, New York 11724 Neurogliaform (RELNϩ) and bipolar (VIPϩ) GABAergic interneurons of the mammalian cerebral cortex provide critical inhibition locally within the superficial layers. While these subtypes are known to originate from the embryonic caudal ganglionic eminence (CGE), the specific genetic programs that direct their positioning, maturation, and integration into the cortical network have not been eluci- dated. Here, we report that in mice expression of the transcription factor Prox1 is selectively maintained in postmitotic CGE-derived cortical interneuron precursors and that loss of Prox1 impairs the integration of these cells into superficial layers. Moreover, Prox1 differentially regulates the postnatal maturation of each specific subtype originating from the CGE (RELN, Calb2/VIP, and VIP). -

Clinical Utility of Recently Identified Diagnostic, Prognostic, And

Modern Pathology (2017) 30, 1338–1366 1338 © 2017 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/17 $32.00 Clinical utility of recently identified diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive molecular biomarkers in mature B-cell neoplasms Arantza Onaindia1, L Jeffrey Medeiros2 and Keyur P Patel2 1Instituto de Investigacion Marques de Valdecilla (IDIVAL)/Hospital Universitario Marques de Valdecilla, Santander, Spain and 2Department of Hematopathology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA Genomic profiling studies have provided new insights into the pathogenesis of mature B-cell neoplasms and have identified markers with prognostic impact. Recurrent mutations in tumor-suppressor genes (TP53, BIRC3, ATM), and common signaling pathways, such as the B-cell receptor (CD79A, CD79B, CARD11, TCF3, ID3), Toll- like receptor (MYD88), NOTCH (NOTCH1/2), nuclear factor-κB, and mitogen activated kinase signaling, have been identified in B-cell neoplasms. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, hairy cell leukemia, and marginal zone lymphomas of splenic, nodal, and extranodal types represent examples of B-cell neoplasms in which novel molecular biomarkers have been discovered in recent years. In addition, ongoing retrospective correlative and prospective outcome studies have resulted in an enhanced understanding of the clinical utility of novel biomarkers. This progress is reflected in the 2016 update of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms, which lists as many as 41 mature B-cell neoplasms (including provisional categories). Consequently, molecular genetic studies are increasingly being applied for the clinical workup of many of these neoplasms. In this review, we focus on the diagnostic, prognostic, and/or therapeutic utility of molecular biomarkers in mature B-cell neoplasms. -

Targeting Iron Homeostasis Induces Cellular Differentiation and Synergizes with Differentiating Agents in Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Article Targeting iron homeostasis induces cellular differentiation and synergizes with differentiating agents in acute myeloid leukemia Celine Callens,1,2 Séverine Coulon,1,2 Jerome Naudin,1,2,3,4 Isabelle Radford-Weiss,2,5 Nicolas Boissel,4,9 Emmanuel Raffoux,4,9 Pamella Huey Mei Wang,3,4 Saurabh Agarwal,3,4 Houda Tamouza,3,4 Etienne Paubelle,1,2 Vahid Asnafi,1,2,6 Jean-Antoine Ribeil,1,2 Philippe Dessen,10 Danielle Canioni,2,7 Olivia Chandesris,2,8 Marie Therese Rubio,2,8 Carole Beaumont,4,11 Marc Benhamou,3,4 Hervé Dombret,4,9 Elizabeth Macintyre,1,2,6 Renato C. Monteiro,3,4 Ivan C. Moura,3,4 and Olivier Hermine1,2,8 1Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique UMR 8147, Paris 75015, France 2Faculté de Médecine, Université René Descartes Paris V, Institut Fédératif Necker, Paris 75015, France 3Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), U699, Paris 75018, France 4Faculté de Médecine, Université Denis Diderot Paris VII, Paris 75018, France 5Laboratoire de cytogénétique, 6Laboratoire d’Hématologie, 7Service d’Anatomo-Pathologie, and 8Service d’Hématologie, Hôpital Necker-Enfants Malades, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), Paris 75015, France 9Service d’Hématologie, Hôpital Saint-Louis, AP-HP, Paris 75010, France 10Unité de Génomique Fonctionnelle, Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif 94800, France 11INSERM U773, Centre de Recherche Biomédicale Bichat Beaujon CRB3, Paris 75018, France Differentiating agents have been proposed to overcome the impaired cellular differentia- tion in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, only the combinations of all-trans retinoic acid or arsenic trioxide with chemotherapy have been successful, and only in treating acute promyelocytic leukemia (also called AML3). -

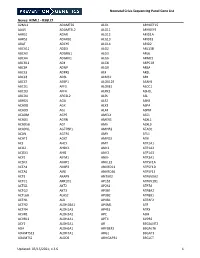

NICU Gene List Generator.Xlsx

Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: A2ML1 - B3GLCT A2ML1 ADAMTS9 ALG1 ARHGEF15 AAAS ADAMTSL2 ALG11 ARHGEF9 AARS1 ADAR ALG12 ARID1A AARS2 ADARB1 ALG13 ARID1B ABAT ADCY6 ALG14 ARID2 ABCA12 ADD3 ALG2 ARL13B ABCA3 ADGRG1 ALG3 ARL6 ABCA4 ADGRV1 ALG6 ARMC9 ABCB11 ADK ALG8 ARPC1B ABCB4 ADNP ALG9 ARSA ABCC6 ADPRS ALK ARSL ABCC8 ADSL ALMS1 ARX ABCC9 AEBP1 ALOX12B ASAH1 ABCD1 AFF3 ALOXE3 ASCC1 ABCD3 AFF4 ALPK3 ASH1L ABCD4 AFG3L2 ALPL ASL ABHD5 AGA ALS2 ASNS ACAD8 AGK ALX3 ASPA ACAD9 AGL ALX4 ASPM ACADM AGPS AMELX ASS1 ACADS AGRN AMER1 ASXL1 ACADSB AGT AMH ASXL3 ACADVL AGTPBP1 AMHR2 ATAD1 ACAN AGTR1 AMN ATL1 ACAT1 AGXT AMPD2 ATM ACE AHCY AMT ATP1A1 ACO2 AHDC1 ANK1 ATP1A2 ACOX1 AHI1 ANK2 ATP1A3 ACP5 AIFM1 ANKH ATP2A1 ACSF3 AIMP1 ANKLE2 ATP5F1A ACTA1 AIMP2 ANKRD11 ATP5F1D ACTA2 AIRE ANKRD26 ATP5F1E ACTB AKAP9 ANTXR2 ATP6V0A2 ACTC1 AKR1D1 AP1S2 ATP6V1B1 ACTG1 AKT2 AP2S1 ATP7A ACTG2 AKT3 AP3B1 ATP8A2 ACTL6B ALAS2 AP3B2 ATP8B1 ACTN1 ALB AP4B1 ATPAF2 ACTN2 ALDH18A1 AP4M1 ATR ACTN4 ALDH1A3 AP4S1 ATRX ACVR1 ALDH3A2 APC AUH ACVRL1 ALDH4A1 APTX AVPR2 ACY1 ALDH5A1 AR B3GALNT2 ADA ALDH6A1 ARFGEF2 B3GALT6 ADAMTS13 ALDH7A1 ARG1 B3GAT3 ADAMTS2 ALDOB ARHGAP31 B3GLCT Updated: 03/15/2021; v.3.6 1 Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: B4GALT1 - COL11A2 B4GALT1 C1QBP CD3G CHKB B4GALT7 C3 CD40LG CHMP1A B4GAT1 CA2 CD59 CHRNA1 B9D1 CA5A CD70 CHRNB1 B9D2 CACNA1A CD96 CHRND BAAT CACNA1C CDAN1 CHRNE BBIP1 CACNA1D CDC42 CHRNG BBS1 CACNA1E CDH1 CHST14 BBS10 CACNA1F CDH2 CHST3 BBS12 CACNA1G CDK10 CHUK BBS2 CACNA2D2 CDK13 CILK1 BBS4 CACNB2 CDK5RAP2 -

Vitamin D Regulates Myeloid Cells Via the Mertk Pathway

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.06.937482; this version posted February 7, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Vitamin D regulates MerTK-dependent phagocytosis in human myeloid cells Running Title: Vitamin D regulates myeloid cells via the MerTK pathway Jelani Clarke1, Moein Yaqubi1, Naomi C. Futhey1, Sara Sedaghat1, Caroline Baufeld3, Manon Blain1, Sergio Baranzini2, Oleg Butovsky3, John H. White4, 5, Jack Antel1, Luke M. Healy1 1Neuroimmunology Unit, Montreal Neurological Institute, Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada 2Department of Neurology, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California-San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA 3Ann Romney Center for Neurologic Diseases, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women′s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA 4Departments of Physiology and Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada 5Evergrande Center for Immunologic Diseases, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA Email address: [email protected] Phone number: (+1) 514-815-1916 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.06.937482; this version posted February 7, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Abstract 1 Vitamin D deficiency is a major environmental risk factor for the development of multiple 2 sclerosis (MS). -

Temporal Mapping of CEBPA and CEBPB Binding

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 26, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Temporal mapping of CEBPA and CEBPB binding during liver regeneration reveals dynamic occupancy and specific regulatory codes for homeostatic and cell cycle gene batteries Janus Schou Jakobsen1,2,3,*, Johannes Waage1,2,3,4, Nicolas Rapin1,2,3,4, Hanne Cathrine Bisgaard5, Fin Stolze Larsen6, Bo Torben Porse1,2,3,* 1 The Finsen Laboratory, Rigshospitalet, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, DK2200 Copenhagen, Denmark; 2 Biotech Research and Innovation Centre (BRIC), University of Copenhagen, DK-2200 Copenhagen, Denmark; 3 The Danish Stem Cell Centre (DanStem) Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, DK2200 Copenhagen Denmark; 4 The Bioinformatics Centre, University of Copenhagen, DK2200, Copenhagen, Denmark; 5 Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, DK- 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark; 6 Department of Hepatology, Rigshospitalet, DK2200 Copenhagen, Denmark. JW: [email protected]; NR: [email protected]; HCB: [email protected]; FSL: [email protected] * Corresponding authors: BTP: [email protected]; JSJ: [email protected], The Finsen Laboratory, Ole Maaløesvej 5, Copenhagen Biocenter, University of Copenhagen, DK2200 Copenhagen, Denmark. Telephone: +45 3545 6023 Running title: Regulation of liver regeneration Keywords: Temporal ChIP-seq, dynamic binding, liver regeneration, C/EBPalpha, C/EBPbeta, transcriptional networks 1 Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 26, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Abstract Dynamic shifts in transcription factor binding are central to the regulation of biological processes by allowing rapid changes in gene transcription. -

The Global Gene Expression Profile of the Secondary Transition During Pancreatic Development

ÔØ ÅÒÙ×Ö ÔØ The global gene expression profile of the secondary transition during pancre- atic development Stefanie J. Willmann, Nikola S. Mueller, Silvia Engert, Michael Sterr, Ingo Burtscher, Aurelia Raducanu, Martin Irmler, Johannes Beckers, Steffen Sass, Fabian J. Theis, Heiko Lickert PII: S0925-4773(15)30037-X DOI: doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2015.11.004 Reference: MOD 3386 To appear in: Received date: 19 June 2015 Revised date: 26 November 2015 Accepted date: 27 November 2015 Please cite this article as: Willmann, Stefanie J., Mueller, Nikola S., Engert, Sil- via, Sterr, Michael, Burtscher, Ingo, Raducanu, Aurelia, Irmler, Martin, Beckers, Johannes, Sass, Steffen, Theis, Fabian J., Lickert, Heiko, The global gene expres- sion profile of the secondary transition during pancreatic development, (2015), doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2015.11.004 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT The global gene expression profile of the secondary transition during pancreatic development Stefanie J. Willmann*1,5, Nikola S. Mueller*2, Silvia Engert1, Michael Sterr1, Ingo Burtscher1, Aurelia Raducanu1, Martin Irmler3, Johannes Beckers3,4,5, -

Identification of Shared and Unique Gene Families Associated with Oral

International Journal of Oral Science (2017) 9, 104–109 OPEN www.nature.com/ijos ORIGINAL ARTICLE Identification of shared and unique gene families associated with oral clefts Noriko Funato and Masataka Nakamura Oral clefts, the most frequent congenital birth defects in humans, are multifactorial disorders caused by genetic and environmental factors. Epidemiological studies point to different etiologies underlying the oral cleft phenotypes, cleft lip (CL), CL and/or palate (CL/P) and cleft palate (CP). More than 350 genes have syndromic and/or nonsyndromic oral cleft associations in humans. Although genes related to genetic disorders associated with oral cleft phenotypes are known, a gap between detecting these associations and interpretation of their biological importance has remained. Here, using a gene ontology analysis approach, we grouped these candidate genes on the basis of different functional categories to gain insight into the genetic etiology of oral clefts. We identified different genetic profiles and found correlations between the functions of gene products and oral cleft phenotypes. Our results indicate inherent differences in the genetic etiologies that underlie oral cleft phenotypes and support epidemiological evidence that genes associated with CL/P are both developmentally and genetically different from CP only, incomplete CP, and submucous CP. The epidemiological differences among cleft phenotypes may reflect differences in the underlying genetic causes. Understanding the different causative etiologies of oral clefts is -

Xo PANEL DNA GENE LIST

xO PANEL DNA GENE LIST ~1700 gene comprehensive cancer panel enriched for clinically actionable genes with additional biologically relevant genes (at 400 -500x average coverage on tumor) Genes A-C Genes D-F Genes G-I Genes J-L AATK ATAD2B BTG1 CDH7 CREM DACH1 EPHA1 FES G6PC3 HGF IL18RAP JADE1 LMO1 ABCA1 ATF1 BTG2 CDK1 CRHR1 DACH2 EPHA2 FEV G6PD HIF1A IL1R1 JAK1 LMO2 ABCB1 ATM BTG3 CDK10 CRK DAXX EPHA3 FGF1 GAB1 HIF1AN IL1R2 JAK2 LMO7 ABCB11 ATR BTK CDK11A CRKL DBH EPHA4 FGF10 GAB2 HIST1H1E IL1RAP JAK3 LMTK2 ABCB4 ATRX BTRC CDK11B CRLF2 DCC EPHA5 FGF11 GABPA HIST1H3B IL20RA JARID2 LMTK3 ABCC1 AURKA BUB1 CDK12 CRTC1 DCUN1D1 EPHA6 FGF12 GALNT12 HIST1H4E IL20RB JAZF1 LPHN2 ABCC2 AURKB BUB1B CDK13 CRTC2 DCUN1D2 EPHA7 FGF13 GATA1 HLA-A IL21R JMJD1C LPHN3 ABCG1 AURKC BUB3 CDK14 CRTC3 DDB2 EPHA8 FGF14 GATA2 HLA-B IL22RA1 JMJD4 LPP ABCG2 AXIN1 C11orf30 CDK15 CSF1 DDIT3 EPHB1 FGF16 GATA3 HLF IL22RA2 JMJD6 LRP1B ABI1 AXIN2 CACNA1C CDK16 CSF1R DDR1 EPHB2 FGF17 GATA5 HLTF IL23R JMJD7 LRP5 ABL1 AXL CACNA1S CDK17 CSF2RA DDR2 EPHB3 FGF18 GATA6 HMGA1 IL2RA JMJD8 LRP6 ABL2 B2M CACNB2 CDK18 CSF2RB DDX3X EPHB4 FGF19 GDNF HMGA2 IL2RB JUN LRRK2 ACE BABAM1 CADM2 CDK19 CSF3R DDX5 EPHB6 FGF2 GFI1 HMGCR IL2RG JUNB LSM1 ACSL6 BACH1 CALR CDK2 CSK DDX6 EPOR FGF20 GFI1B HNF1A IL3 JUND LTK ACTA2 BACH2 CAMTA1 CDK20 CSNK1D DEK ERBB2 FGF21 GFRA4 HNF1B IL3RA JUP LYL1 ACTC1 BAG4 CAPRIN2 CDK3 CSNK1E DHFR ERBB3 FGF22 GGCX HNRNPA3 IL4R KAT2A LYN ACVR1 BAI3 CARD10 CDK4 CTCF DHH ERBB4 FGF23 GHR HOXA10 IL5RA KAT2B LZTR1 ACVR1B BAP1 CARD11 CDK5 CTCFL DIAPH1 ERCC1 FGF3 GID4 HOXA11 -

MAFB Promotes Cancer Stemness and Tumorigenesis in Osteosarcoma Through a Sox9-Mediated Positive Feedback Loop

Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on March 31, 2020; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-1764 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. MAFB promotes cancer stemness and tumorigenesis in osteosarcoma through a Sox9-mediated positive feedback loop Yanyan Chen1,†, Bin Wang2, †, Mengxi Huang1, †, Tao Wang 2, †, Chao Hu 3,†, Qin Liu 2, Dong Han 4, Cheng Chen1, Junliang Zhang5, Zhiping Li4, Chao Liu 6, Wenbin Lei 7,Yue Chang1, Meijuan Wu1,Dan Xiang1, Yitian Chen1, Rui Wang1, Weiqian Huang5, Zengjie Lei1 ,* and Xiaoyuan Chu1, * 1 Department of Medical Oncology, Affiliated Jinling Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, People’s Republic of China 2 Department of Gastroenterology, Daping Hospital, Third Military Medical University (Ar- my Medical University), Chongqing, People’s Republic of China 3 Department of Orthopedics, 904 Hospital of PLA, North Xingyuan Road, Beitang Dis- trict, Wuxi, Jiangsu, People’s Republic of China 4 Department of Medical Oncology, Jinling Hospital, Nanjing Clinical School of Southern Medical University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, People’s Republic of China 5 Department of Orthopedics, Affiliated Jinling Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing Univer- sity, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, People’s Republic of China 6 Department of Medical Oncology, Jinling Hospital, Nanjing Clinical School of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, People’s Republic of China 7Department of Orthopedics, Tianshui Cooperation of Chinese and Western Medicine Hospi- tal, Tianshui, Gansu Province, People’s Republic of China * To whom correspondence should be addressed. Xiaoyuan Chu, Tel: +86-25-80860131, Fax: +86-25-80860131, Email: [email protected]; Zengjie Lei, Email: leiz- [email protected] ; †The authors wish it to be known that, in their opinion, the first five authors should be regard- ed as joint First Authors.