Anzsog Case Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

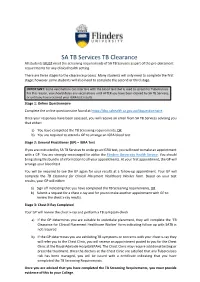

SA TB Services TB Clearance

SA TB Services TB Clearance All students MUST meet the screening requirements of SA TB Services as part of the pre-placement requirements for any clinical health setting. There are three stages to the clearance process. Many students will only need to complete the first stage; however some students will also need to complete the second or third stage. IMPORTANT: Some vaccinations can interfere with the blood test that is used to screen for Tuberculosis. For this reason, you should delay any vaccinations until AFTER you have been cleared by SA TB Services, or until you have received your IGRA test results. Stage 1: Online Questionnaire Complete the online questionnaire found at https://tbq.sahealth.sa.gov.au/tbquestionnaire. Once your responses have been assessed, you will receive an email from SA TB Services advising you that either: a) You have completed the TB Screening requirements, OR b) You are required to attend a GP to arrange an IGRA blood test Stage 2: General Practitioner (GP) – IGRA Test If you are instructed by SA TB Services to undergo an IGRA test, you will need to make an appointment with a GP. You are strongly encouraged to utilise the Flinders University Health Service. You should bring along this bundle of information to all your appointments. At your first appointment, the GP will arrange your blood test. You will be required to see the GP again for your results at a follow-up appointment. Your GP will complete the TB Clearance for Clinical Placement Healthcare Worker form. Based on your test results, your GP will either: a) Sign off indicating that you have completed the TB Screening requirements, OR b) Submit a request for a chest x-ray and for you to make another appointment with GP to review the chest x-ray results. -

Our Cultural Collections a Guide to the Treasures Held by South Australia’S Collecting Institutions Art Gallery of South Australia

Our Cultural Collections A guide to the treasures held by South Australia’s collecting institutions Art Gallery of South Australia. South Australian Museum. State Library of South Australia. Car- rick Hill. History SA. Art Gallery of South Aus- tralia. South Australian Museum. State Library of South Australia. Carrick Hill. History SA. Art Gallery of South Australia. South Australian Museum. State Library of South Australia. Car- rick Hill. History SA. Art Gallery of South Aus- Published by Contents Arts South Australia Street Address: Our Cultural Collections: 30 Wakefield Street, A guide to the treasures held by Adelaide South Australia’s collecting institutions 3 Postal address: GPO Box 2308, South Australia’s Cultural Institutions 5 Adelaide SA 5001, AUSTRALIA Art Gallery of South Australia 6 Tel: +61 8 8463 5444 Fax: +61 8 8463 5420 South Australian Museum 11 [email protected] www.arts.sa.gov.au State Library of South Australia 17 Carrick Hill 23 History SA 27 Artlab Australia 43 Our Cultural Collections A guide to the treasures held by South Australia’s collecting institutions The South Australian Government, through Arts South Our Cultural Collections aims to Australia, oversees internationally significant cultural heritage ignite curiosity and awe about these collections comprising millions of items. The scope of these collections is substantial – spanning geological collections, which have been maintained, samples, locally significant artefacts, internationally interpreted and documented for the important art objects and much more. interest, enjoyment and education of These highly valuable collections are owned by the people all South Australians. of South Australia and held in trust for them by the State’s public institutions. -

Quality Assurance Workbook for Radiographers & Radiological Technologists

(/ J . ' WHO/DIUOU DISTRIBUTION: GENERAL ORIGINAL: ENGLISH Quality assurance workbook for radiographers & radiological technologists by Peter J Lloyd MIR, OCR, ARMI~ Grad Dip FEd Lecturer (retired), School of Medical Radiation, University of South Australia Diagnostic Imaging and Laboratory Technology Blood Safety and Clinical Technology Health Technology' and Pharmaceuticals WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Geneva © World Health Organization, 2001 This document is not a formal publication of the World Health Organization (WHO), and all rights are reserved by the Organization. The document may, however, be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced and translated, in part or in whole, but not for sale for use in conjunction with commercial purposes. The views expressed in documents by named authors are solely the responsibility of those authors. Designed in New Zealand Typeset in Hong l<ong Printed in Malta 2001/13663- minimum graphics/Best Set/Interprint- 3000 Ill Contents Introductory remarks vii Acknowledgements viii Introduction 1 Purpose of this workbook 1 Who this workbook is aimed at 2 What this workbook aims to achieve 2 Summary of this workbook 2 How to use this workbook 2 Roles and responsibilities 3 Questionnaire-student's own department 5 Pretest 7 Teaching techniques 10 Overview of teaching methods in common use 10 Assessment 10 Teacher performance 12 Suggested method of teaching with this workbook 12 Conclusions 12 Health and safety 15 Machinery 15 Electrical 15 Fire 15 Hazardous chemicals 16 Radiation 16 Working with the patient 17 Disaster 17 Module 1. Reject film analysis 19 Setting up a reject film analysis program 19 Method 20 Analysis 20 Action 20 Tasks to be carried out by the student 24 Module 2. -

Adelaide, South Australia... Now Is the Time! Now Is the Time!

ADELAIDE, SOUTH AUSTRALIA... NOW IS THE TIME! NOW IS THE TIME! Adelaide, South Australia is positioning itself on a global scale for major conventions. The destination is currently undergoing an unprecedented level of infrastructure development and investment, which will further enhance the city’s already renowned ‘ease of use’ functionality and services to the Business Events sector. A vital component is the re-development of Adelaide’s ‘Riverbank Precinct’ - home to Adelaide Convention Centre, Adelaide Oval, Adelaide Festival Centre, Adelaide Casino, InterContinental Adelaide and surrounding plazas. This area is developing as a world-class convention and entertainment precinct creating a lively and connected promenade including a footbridge linking the Adelaide Oval and northern side of the River Torrens. Complementing these developments is a world leading Health and Medical Research Institute, and other key health and medical developments, cementing Adelaide’s reputation as a hub for related conventions. Adelaide Convention Bureau CEO Damien Kitto underlines the importance of this commitment; “As we all know, to be successful in the global convention market, a destination must have the right mix, standard and location of core convention infrastructure. By enhancing and growing the Riverbank precinct Adelaide is not only able to service major conventions of 3000+ delegates, but is also creating unique synergies with institutions that will drive and support convention content. Our city has great ambition and intention in this area.” MERCURE -

A New Masterplan for Adelaide's Riverbank Precinct

Sourceable Industry News & Analysis http://sourceable.net A New Masterplan for Adelaide’s Riverbank Precinct Author : kristen-avis The South Australian government has begun consultations on what should be done in four integral areas including Bonython Park, the old Royal Adelaide Hospital (RAH) site, the core entertainment area, and the biomedical precinct in order to link the CBD and North Adelaide to attract more activity and investment. Premier Jay Weatherill is confident of the potential of Adelaide’s Riverbank precinct, saying it “will be better than anything other major Australian cities have to offer,” offering Sydney’s Darling Harbour and Melbourne’s Docklands as comparisons. The precinct will include entertainment, retail, arts and sport facilities with work ranging from redevelopment of the Festival Centre to a $40 million footbridge across the Torrens, upgrades to the Adelaide Casino, and the redeveloped Adelaide Oval. Weatherill admits Adelaide has never fully used the river to its advantage but says the new plan will create a new identity for the city with a busy park in the middle of Adelaide. “The River Torrens winding through the heart of Adelaide is one of our city’s best assets,” he says. Adelaide Footbridge Construction Weatherill is inviting South Australians to voice their opinions on how to best revamp the area. Deputy Premier and Planning Minister John Rau says the implementation plan for the Riverbank precinct will be displayed at the Adelaide Convention Centre on June 30. 1 / 3 Sourceable Industry News & Analysis http://sourceable.net Developers hope to finalise a blueprint for the area by August. -

RAH Researcher Spring Raising Funds for Life-Saving Medical Research at the 2020 Royal Adelaide Hospital

RAH Researcher Spring Raising funds for life-saving medical research at the 2020 Royal Adelaide Hospital Nursing Scholarships. Help our nurses improve patient experiences and care. See page 4 Amanda Fleming, Accredited Nurse in General Medicine (left) and Bernadette (Bernie) Fernandez, Nurse Unit Manager for General Medicine (right) providing patient care at the Royal Adelaide Hospital. Researcher Profile Dr Stuart Callary “Personally, I would like to say a sincere Dr Stuart Callary is Senior Medical thank you to all Scientist for the Department of donors to the RAH Orthopaedics and Trauma, Royal Research Fund.” Adelaide Hospital and a Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Dr Stuart Callary Orthopaedic and Trauma Research, University of Adelaide. His research Welcome and a warm ‘thank you’ to our wonderful donors and supporters. focusses on improving outcomes for patients undergoing total hip Despite the many challenges we have all faced this year, your commitment replacement (THR) and surgery has not wavered. We all feel so very fortunate to have your continued to treat lower limb fractures. support for the Royal Adelaide Hospital (RAH) Research Fund. He has just received the Royal Adelaide Hospital (RAH) In this issue of RAH Researcher, This is a time in history when we have Many of you, as former nurses yourselves, Research Fund’s three-year the team has carefully collated a relied heavily on the combined efforts of will particularly enjoy our journey ‘back in range of entertaining and informative our frontline workers and ‘behind the time’ on pages 8 and 9 as we explore how Mary Overton Fellowship. -

Mental Health and Alcohol and Other Drug Services for Salisbury & Playford

2014 DIRECTORY MENTAL HEALTH AND ALCOHOL AND OTHER DRUG SERVICES FOR SALISBURY & PLAYFORD Types of services listed Aboriginal Goverment Non-Government Community Controlled Self-Help Groups Problem Gambling Services Acknowledgements The Comorbidity Action in the North (CAN) Research Team and its Partners. University of Adelaide With special thanks to Imelda Cairney, Sarah Lowes, Sarah Scott and Morgan Glazbrook. Produced by Comorbidity Action in the North (CAN) Research Project ISBN 978-0-9872126-5-8 ©The University of Adelaide, School of Nursing blogs.adelaide.edu.au/nursing/ 3 Important Phone Numbers 24 hours, 7 days/week Free Help, Advice, Information, Referral Emergency 000 SA Police – non urgent 13 14 44 SA Ambulance – enquiries 1300 13 6272 Poison Information Centre Australia 13 11 26 Alcohol and Drug Information Service 1300 13 1340 Mental Health Triage 13 14 65 Crisis Care 13 16 11 Kids Helpline 1800 55 1800 Reliable Websites www.ahcsa.org.au www.dassa.sa.gov.au www.sandas.org.au www.beyondblue.org.au www.mind.org.au www.orygen.org.au http://au.reachout.com/ www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/ 4 Table of contents MENTAL HEALTH AND ALCOHOL AND OTHER DRUG SERVICES FOR SALISBURY & PLAYFORD 1 2014 DIRECTORY 1 Important Phone Numbers 4 Reliable Websites 4 ABORIGINAL SERVICES – ADULT 8 Services in Salisbury & Playford Areas 8 Aboriginal Sobriety Group Inc 8 Northern Adelaide Medicare Local (formerly Adelaide Northern Division of General Practice) 8 Muna Paiendi 8 Nunkuwarrin Yunti of South Australia Inc 8 Metropolitan Services with in-reach -

SA Health Job Pack

SA Health Job Pack Job Title Ward Attendant - Hampstead Dialysis Job Number 620433 Applications Closing Date 28/4/17 Region / Division Central Adelaide Local Health Network Health Service The Royal Adelaide Hospital Location Adelaide Classification WHA-2 Job Status Permanent part-time working 24 hours per week Salary $910.40/$921.10 per week Criminal History Assessment Applicants will be required to demonstrate that they have undergone an appropriate criminal and relevant history screening assessment/ criminal history check. Depending on the role, this may be a Department of Communities and Social Inclusion (DCSI) Criminal History Check and/or a South Australian Police (SAPOL) National Police Check (NPC). The following checks will be required for this role: Child Related Employment Screening - DCSI Vulnerable Person-Related Employment Screening - NPC Aged Care Sector Employment Screening - NPC General Employment Probity Check - NPC Further information is available on the SA Health careers website at www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/careers - see Career Information, or by referring to the nominated contact person below. Contact Details Full name Dylan Carter Phone number 0457 863 685 Email address [email protected] Public – I1 – A1 Guide to submitting an application Thank you for considering applying for a position within SA Health. Recruitment and Selection processes across SA Health are based on best practice and a commitment to a selection based on merit. This means treating all applications in a fair and equitable manner that aims to choose the best person for the position. A well presented, easy to read application will allow the panel to assess the information they need from your application. -

The Right Remedy

The $345M Calvary Adelaide Hospital is a state-of-the-art healthcare facility comprising 344 beds, THE RIGHT REMEDY 16 operating theatres, a 24 hour emergency department, rehabilitation wing with hydrotherapy pool and mobility garden, a custom designed Hybrid Theatre. The new hospital offers the most comprehensive CLIENT : Calvary Health Care DEVELOPER : Commercial & General range of services ever delivered by a private healthcare facility in Adelaide including orthopedic, MAIN CONSTRUCTION COMPANY : John Holland cardiac, neurosurgical, and rehabilitation specialties. ARCHITECT : Silver Thomas Hanley STRUCTURAL ENGINEER : Mott MacDonald CONSTRUCTION VALUE : $345 million The new $345 million Calvary Adelaide 6 to 12 have a unitised curtain wall with John Holland are a Tier One infrastructure, Hospital is the largest private hospital in distinctive blue glass. The podium has a property and building company that South Australia and will provide services rectangular footprint with an impressive distinguishes themselves from their previously supplied by Calvary Wakefield 2-storey entrance, a 24 hour emergency competitors by having a vast network and Calvary Rehabilitation hospitals department, 16 operating theatres and of resources that includes the skills and including orthopaedic, cardiac and four procedure rooms. There is also a knowledge of their people, and support is neurosurgical specialities. medical imaging centre and a pathology always available from its highly experienced laboratory as well as new consulting suites, managers and supervisors. Calvary Adelaide Hospital enhances the staff and administration areas. From Level modern patient experience by providing a 6 upwards are patient rooms, the ICU John Holland’s core construction projects ‘hotel’ feeling. There are 344 beds in single and a rehabilitation wing complete with have been within the infrastructure sector patient rooms with ensuite bathrooms and hydrotherapy pool and mobility garden. -

A Situation Analysis on PACS Prospects for a Developing Nation

Current Practice A Situation Analysis on PACS prospects for a Developing Nation Dr. K. K. Pradeep Sylva BDS Dental Surgeon and Postgraduate Trainee in Biomedical Informatics Postgraduate Institute of Medicine University of Colombo Sri Lanka E-mail: [email protected] Dr. M.K.D.R Buddika Dayaratne MBBS Medical Officer and Postgraduate Trainee in Biomedical Informatics Postgraduate Institute of Medicine University of Colombo Sri Lanka Dr. Udithamala Priyanthi Ratnayake MBBS, MD (Radiology), FRCR (UK) Consultant Radiologist Department of Radiology District General Hospital Nuwaraeliya, Sri Lanka. Dr. K. K. Samanta Sylva MBBS, MD (Radiology) Fellow in Women’s Imaging Royal Adelaide Hospital South Australia Australia Sri Lanka Journal of Bio-Medical Informatics 2010;1(2):112-117 DOI: 10.4038/sljbmi.v1i2.1730 Abstract Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS) provides a digital radiological workflow environment to improve efficacy and efficiency in patient care. The traditional film based system existing in Sri Lanka is fast becoming obsolete with an array of shortcomings and drawbacks such as high turnaround time, film loss and high cost of generation, storage and transport. PACS in combination with the Hospital Information System (HIS) and the Radiological Information System (RIS) provides seamless integration of patient and administrative data to digital images. It also provides remote and multiple accesses to all digital images and image manipulation, thus, providing solutions for current issues in Sri Lanka. Though, with an ocean of benefits around the corner the practical application of such a system is indeed not straight forward for a developing nation with limited resources. The practical implications of the lack of basic technology, network infrastructure, qualified personnel, strategy and legal backing need to be addressed. -

Former Royal Adelaide Hospital Site Master Plan

Former Royal Adelaide Hospital Site Master Plan January 2018 Design Leader Project Director Alex Hall Thomas Masullo Associate Principal Director Woods Bagot Woods Bagot © Woods Bagot 11 Waymouth Street 11 Waymouth Street Australia: Woods Bagot Pty Ltd Adelaide SA 5001 Adelaide SA 5001 ABN 41 007 762 174 Australia Australia Telephone +61 8 8113 5900 Telephone +61 8 8113 5900 Date of issue: JANUARY 2018 [email protected] [email protected] Revision: A WOODSBAGOT.COM Page 2 Introduction 01 Context 02 Vision 03 Design Principles 04 Master Plan 05 Precinct Objectives 06 Appendix Place Strategy A Urban Trends B Economic Assessment C FORMER ROYAL ADELAIDE HOSPITAL SITE MASTER PLAN Page 3 WOODSBAGOT.COM Page 4 Introduction. FORMER ROYAL ADELAIDE HOSPITAL SITE MASTER PLAN Page 5 Executive Summary Deloitte has concluded that to maximise Combining many of the city’s greatest the economic contribution the site strengths; it’s artistic depth, entrepreneurial Precincts Adelaide’s can make through the development of spirit, natural beauty, heritage architecture The master plan breaks the site down into industries where South Australia has a and most importantly, its energy – this key precincts. We have defined the role of competitive advantage, the economic uses international commercial hub will showcase each precinct and the steps that need to that complement the site are; dramatic new spaces that connect and be taken to achieve the desired character allow global organisations, entrepreneurial and vision. Creation and _Attracting digital and technology and creative talents to take their ideas and businesses connected to the research inventions across global markets. -

Organisation Award Category Year Last

Organisation Award Category Year Last Name First Name Institution Prime Minister's Prize for Excellence in Science 2019 Finney Sarah Stirling East Primary School Prime Minister's Teaching in Primary Australian Government Prizes for Science Schools Prime Minister's Prize for Excellence in Science 2019 Moyle Samantha Brighton Secondary School Prime Minister's Teaching in Secondary Australian Government Prizes for Science Schools Prime Minister's University of South Prize for New Innovators 2016 Hall Colin Australian Government Prizes for Science Australia Prime Minister’s Prize for Excellence in Science 2014 Schiller Brian Seacliff Primary School Prime Minister's Teaching in Primary Australian Government Prizes for Science Schools Prime Minister’s Prize for Excellence in Science 2012 Trenwith Anita Salisbury High School Prime Minister's Teaching in Secondary Australian Government Prizes for Science Schools Australian Institute of Young Tall Poppy South Australia 2019 Cohen-Woods Sarah Flinders University Policy and Science Science Awards Australian Institute of Young Tall Poppy University of South South Australia 2019 Tina Du Jia Policy and Science Science Awards Australia Australian Institute of Young Tall Poppy South Australia 2019 Griffiths Oren Flinders University Policy and Science Science Awards Australian Institute of Young Tall Poppy University of South South Australia 2019 Nguyen Giang Policy and Science Science Awards Australia Australian Institute of Young Tall Poppy University of Adelaide & South Australia 2019 Rogasch Nigel