Print ED376490.TIF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beginnings of English Protestantism

THE BEGINNINGS OF ENGLISH PROTESTANTISM PETER MARSHALL ALEC RYRIE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge ,UK West th Street, New York, -, USA Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, , Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on , Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town , South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Baskerville Monotype /. pt. System LATEX ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library hardback paperback Contents List of illustrations page ix Notes on contributors x List of abbreviations xi Introduction: Protestantisms and their beginnings Peter Marshall and Alec Ryrie Evangelical conversion in the reign of Henry VIII Peter Marshall The friars in the English Reformation Richard Rex Clement Armstrong and the godly commonwealth: radical religion in early Tudor England Ethan H. Shagan Counting sheep, counting shepherds: the problem of allegiance in the English Reformation Alec Ryrie Sanctified by the believing spouse: women, men and the marital yoke in the early Reformation Susan Wabuda Dissenters from a dissenting Church: the challenge of the Freewillers – Thomas Freeman Printing and the Reformation: the English exception Andrew Pettegree vii viii Contents John Day: master printer of the English Reformation John N. King Night schools, conventicles and churches: continuities and discontinuities in early Protestant ecclesiology Patrick Collinson Index Illustrations Coat of arms of Catherine Brandon, duchess of Suffolk. -

Building the Foundation for Close Reading with Developing Readers

BUILDING THE FOUNDATION FOR CLOSE READING WITH DEVELOPING READERS SHEILA F. BAKER AND LILLIAN MCENERY ABSTRACT Close Reading utilizes several strategies to help readers think more critically about a text. Close reading can be performed within the context of shared readings, read-alouds by the teacher, literature discussion groups, and guided reading groups. Students attempting to more closely read difficult texts may benefit from technologies and platforms that support their diverse reading levels, abilities, and special needs during close reading activities. The authors identify technologies which enable teachers to embed multimedia, interactive activities, and questions and activities that promote critical thinking and which guide readers to take a closer look at the content of their texts. Close reading is a term that has been with us for some time. As early as 1838, Horace Mann wrote, I have devoted especial pains to learn, with some degree of numerical accuracy, how far the reading, in our schools, is an exercise of the mind in thinking and feeling and how far it is a barren action of the organs of speech upon the atmosphere (p, 531).....The result is, that more than eleven-twelfths of all the children in the reading classes, in our schools, do not understand the meaning of the words they read; that they do not master the sense of the reading-lessons, and that the ideas and feelings intended by the author to be conveyed to, and excited in, the reader’s mind, still rest in the author’s intention, never having yet reached the place of their destination (p. -

Designing Fiction-Based Close Reading Experiences for the High School English Language Arts Classroom

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects January 2015 Designing Fiction-Based Close Reading Experiences For The iH gh School English Language Arts Classroom Aubrey Jean Mcnary Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Mcnary, Aubrey Jean, "Designing Fiction-Based Close Reading Experiences For The iH gh School English Language Arts Classroom" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1811. https://commons.und.edu/theses/1811 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright 2015 Aubrey McNary ii PERMISSION Title Designing Fiction-Based Close Reading Experiences for the High School English Language Arts Classroom Department Teaching and Learning Degree Master of Science In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the library of this University shall make if freely available for inspection. I further agree that the permission for extensive copying for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my thesis work or, in her absence, by the chairperson of the department or the dean of the School of Graduate Studies. It is understood that any copying or publication or other use of this thesis or part thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

A Teacher's Introduction to Composition in the Rhetorical Tradition

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 373 330 CS 214 452 AUTHOR Winterowd, W. Ross; Blum, Jack TITLE A Teacher's Introduction to Composition in the Rhetorical Tradition. NCTE Teacher's Introduction Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-5024-1; ISSN-1059-0331 PUB DATE 94 NOTE _42p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 50241-3050: $8.95 members, $11.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Books (010) Historical Materials (060) Guides Non- Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational History; English Curriculum; English Instruction; Higher Education; *Intellectual History; *Rhetorical Theory; *Writing (Composition); *Writing Instruction IDENTIFIERS *Classical Rhetoric; *Composition Theory; Historical Background; Poststructuralism ABSTRACT Based on the idea that an individual cannot understand literature, philosophy, or rhetoric without knowing the field's historical content, this book traces the evolution of the growing and ever-changing field of composition/rhetoric through numerous schools of thought, including Platonism, Aristoteleanism, New Criticism, and the current poststructuralism. After a discussion of the main themes of classical rhetoric, the book offers a historical analysis of the rhetoric of 18th and 19th centuries, focusing briefly on the works of George Campbell, Hugh Blair, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. The book divides the current field of composition/rhetoric into five categories: current-traditio:. 1 rhetoric, romantic rhetoric, neo-classical rhetoric, new rhetoric, and new stylistics. An entire chapter in the book is devoted to the work of I. A. Richards and Kenneth Burke. The final chapter of the book offers an analysis of poststructuralism influence on composition--discussing New Criticism, deconstruction, feminist criticism, and postmodernism. -

Close Reading As an Intervention for Struggling Middle School Readers

FEATURE ARTICLE Close Reading as an Intervention for Struggling Middle School Readers D o u g l a s F i s h e r & N a n c y F r e y An after- school reading intervention made a difference for struggling middle school students. But what made the difference? Close reading, peer collaboration, and wide reading of young adult literature. ized intensive reading interventions in groups of two housands of adolescents across the world are to four students. According to the researchers’ find- participating in a wide range of intervention ings, participants “demonstrated significantly higher efforts designed to improve their literacy scores than comparison students on standardized mea- Tachievement (Calhoon, Scarborough, & Miller, 2013 ). sures of comprehension (effect size = 1.20) and word These efforts include additional classes during the identification (effect size = 0.49), although most con- regular school day, after school, and in summer pro- tinued to lack grade- level proficiency in reading de- grams, as well as computerized interventions (Hartry, spite three years of intervention” (p. 515). Cantrell Fitzgerald, Porter, 2008 ; Soper & Marquis- Cox, 2012 ). and colleagues ( 2010 ) reported on a reading interven- Given that millions of dollars are spent each year fo- tion effort focused on comprehension strategy instruc- cused on students who have fallen behind their peers tion, the Learning Strategies Curriculum, which is in literacy development, the effectiveness of these part of the Strategies Intervention Model (Tralli, intervention efforts is an important consideration. Colombo, Deshler, & Schumaker, 1996 ). This study Thankfully, evidence suggests that reading focused on word identification, vocabulary, visualiz- interventions with adolescents can be effective. -

The Picture of Nobody: Shakespeare's Anti-Authorship

The Picture of Nobody: Shakespeare’s anti-authorship RICHARD WILSON Contributor: Richard Wilson is the Sir Peter Hall Professor of Shakespeare Studies at Kingston University, London. His books include Will Power, Secret Shakespeare, and Shakespeare in French Theory. He is the author of numerous articles in academic journals, and is on the editorial board of the journal Shakespeare. 1. Bare life At the end, ‘his nose was as sharp as a pen’ as he ‘babbled of green fields’ (Henry V, 2,3,15). In September 1615, a few weeks before Shakespeare began to make his will and a little over six months before his death, Thomas Greene, town clerk of Stratford, wrote a memorandum of an exchange biographers treasure as the last of the precious few records of the dramatist’s spoken words: ‘W Shakespeares tellyng J Greene that I was not able to beare the enclosinge of Welcombe’.1 John Greene was the clerk’s brother, and Shakespeare, according to previous papers, was their ‘cousin’, who had lodged Thomas at New Place, his Stratford house. So the Greenes had appealed to their sharp-nosed kinsman for help in a battle that pitted the council against a consortium of speculators who were, in their own eyes, if ‘not the greatest… almost the greatest men of England’.2 The plan to enclose the fields of Welcombe north of the town was indeed promoted by the steward to the Lord Chancellor, no less. But the predicament for Shakespeare was that it was led by his friends the Combes, rich money-lenders from whom he had himself bought 107 acres adjacent to the scheme. -

Close Reading & Text Complexity

Close Reading & Text Complexity Selecting the best texts and strategies to engage and challenge our students. First Impressions Lisa Jones-Farkas Handouts Reading Coach @ Brandon Blue: Note-taking sheet High School; Hillsborough Cream: Text Complexity County Schools Email: Goldenrod: Word [email protected] Questioning Agenda: Green: Charting the Text Text Complexity Overview & White: PowerPoint Tools and Close-Reading Yellow: Doug Fisher Overview & Strategies for the classroom article Please read Order of Importance: through the • Ask text-dependent characteristics of questions close reading and • Establish a purpose for place them in reading order of importance. Most • Encourage text marking important at the • Select text of appropriate top and least at size & complexity the bottom. • Check for understanding • Provide discussion time • Engaging text for students Order will • Select text of appropriate vary… size • Establish a purpose for Just be sure to reading remember these • Provide discussion time key factors when • Encourage text marking choosing texts and strategies • Check for understanding for close reading. • Engaging text for students • Asking text-dependent questions Today’s Focus: Power Standards Text Complexity is: “The inherent difficulty of reading and comprehending a text combined with consideration of reader and task variables; in the Standards, a three-part assessment of text difficulty that pairs qualitative and quantitative measures with reader-task considerations.” CCSS Appendix A Measuring Text Complexity • Quantitative measures look at factors impacting “readability” as measured by particular computer programs. • Qualitative measures examine levels of meaning, knowledge demands, language features, text structure, and use of graphics as measured by an attentive reader. • Reader and Task considers additional “outside” factors that might impact the difficulty of reading the text. -

Close Reading and Far-Reaching Classroom Discussion: Fostering a Vital Connection

Close Reading and Far-Reaching Classroom Discussion: Fostering a Vital Connection by Catherine Snow Graduate School of Education, Harvard University Catherine O’Connor School of Education, Boston University September 13, 2013 A Policy Brief from the Literacy Research Panel of the International Reading Association Close Reading and Far-Reaching Classroom Discussion: Fostering a Vital Connection by Catherine Snow Graduate School of Education, Harvard University Catherine O’Connor School of Education, Boston University One of the widespread anticipatory reactions to the texts (Pearson, 2013). Those practices include, in the Common Core State Standards is a new emphasis in elementary grades, considerable anticipatory work before guidance to practitioners on “close reading” (Brown & the texts are broached. Kappes, 2012). Close reading is an approach to teaching For example, a familiar approach to illustrated narrative comprehension that insists students extract meaning from texts is to start with a ‘picture walk’ (Clay, 1991; Fountas & text by examining carefully how language is used in the Pinell, 1996), constructing the story from the pictures passage itself. It stems from the observation that many before considering the text. This practice is assumed to students emerging from the K-12 world are not ready to pique students’ interest and to build their abilities to predict engage with complex text of the kind they must work with and interpret—useful capacities, but no reason to limit in college. Its ultimate goal is to help students strengthen access to the text itself as a basis for predicting and their ability to learn from complex text independently, and interpreting. thus to enhance college and career readiness. -

Close Reading.Pdf

Ed Camp 2015 Hope Scherlin “A significant body of research links the close reading of complex text- whether the student is a struggling reader or advanced- to significant gains in reading proficiency and finds close reading to be a key component of college and career readiness.”(Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers, 2011, p7) CCSS expects students to be able to: read complex text write to the text examine meaning A thoughtful, critical analysis of text that focuses on significant details or patterns to develop a deep, precise understanding of the text. Most reading grazes the surface of a text; Close Reading digs deeper to uncover the meaning of the text. Short, complex text Limited pre-reading activities- Allows students to discover the meaning on their own Deliberately read and REREAD Discuss with others Respond to text-dependent questions Questions rooted in the text- no personal or text to self connections Consider Text Complexity Text and sentence structure, vocabulary, knowledge demands of the reader Readability Level Reader and Task Measures Prior knowledge, topic, interests, reading skills, etc. You know your students! Text Dependent Questions- cannot be answered with out using the text encourage a deep consideration of the text Requires students to be thoughtful readers Teaches students to think as they read- What is the author telling me here? Are there any hard or important words? What does the author want me to understand? How does the author play with language to add meaning? There is no specific sequence to Close Reading. This is a guide to help you scaffold the lesson focusing on increasing complexity. -

Marius, Richard. After The

Boston Globe, May 17, 1992 AFTER THE WAR By Richard Marius Alfred A. Knopf. 637 pp. In 1977, one year before he left Tennessee to head Harvard's expository writing program, history professor/novelist Richard Marius described a novel-in-progress about "an immigrant who arrives in Bourbonville [Tennessee] in the autumn of 1917. He has been wounded fighting in the Belgian army, and now he must make a new existence for himself. His coming unhinges the town." Fifteen years later, opulently enlarged, the plan once entitled The Immigrant emerges as Marius's third novel, After the War. It is not merely good. It is amazingly good. The book does, however, take its time clenching us in its grasp. Rather, we drift in, disoriented and wary, like the novel's protagonist, Paul Alexander. Born Greek and educated in Belgium, Paul has spent almost three years recovering from a shrapnel wound suffered early in World War I. Vaguely hoping to find the father who abandoned him, Paul wanders to east Tennessee where he takes a job as chemist in a Bourbonville railroad iron foundry. Yet Paul is lost at the intersection of now and then. Wherever he turns he sees the specters of Guy and Bernal, his vibrant schoolmates, both killed at the dawn of the war, both everpresent in Tennessee to remind him they've sworn to remain together always. For the first third of the novel, Marius braids the stories of Paul in Belgium and Paul in Tennessee. They yield an achingly engrossing character, a studious boy grown into a pained young man who has recovered neither in body from his wounds nor in spirit from the deaths of his friends. -

A Close Look at Close Reading (PDF)

A Close Look at Close Reading Scaffolding Students with Complex Texts Beth Burke, NBCT [email protected] Table of Contents What Is Close Reading? ....................................................................................................................... 2 Selecting a Text .................................................................................................................................... 3 What Makes Text Complex? ................................................................................................................ 4 Steps in Close Reading ........................................................................................................................ 5 Scaffolding Students in Close Reading .............................................................................................. 6 Close Reading Template ...................................................................................................................... 7 Close Reading Sample Lesson ............................................................................................................ 8 Spelunking (article) .............................................................................................................................. 9 Text Dependent Questions ................................................................................................................ 10 [email protected] 1 What Is Close Reading? Close reading is thoughtful, critical analysis of a text that focuses on significant details or patterns -

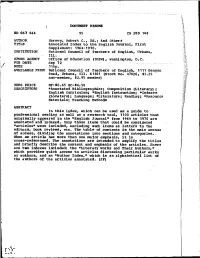

And Others Annotated Index to the English Journal, First

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 067 664 95 CS 200 140 AUTHOR Harvey, Robert C., Ed.; And Others TITLE Annotated Index to the English Journal, First Supplement: 1964-1970. INSTITUTION- National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DUEW), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Sep 72 NOTE 115p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Road, Urbana, III. 61801 (Stock No..47826, $3.25 non-member, $2.95 member) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies; Composition (Literary) ; English Curriculum; *English Instruction; *Indexes (Locaters); Language; *Literature; Reading; *Resource Materials; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT In this index, which can be used as a guide to professional reading as well as a research tool, 1100 articles that originally appeared in the "English Journal" from 1964 to 1970 are annotated and indexed. Only those items that could be considered "articles" were included, excluding such items as letters to the editors, book reviews, etc. The table of contents is the main avenue of access, dividing the annotations into sections and categories. When an article has more than one major emphasis, it is cross-referenced. The annotations are intended to amplify the titles and briefly describe the content and emphasis of the articles. There are two indexes included: the "Literary Works and Their Authors," which provides quick access to articles discussing particular works or authors, and an "Author Index," which is an alphabetical list of the authors of the articles annotated. (JF) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE 7. f EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT VAS BEEN REPRO.