Mabel Fairbanks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coaches... RENEW for the NOW

USPS #017-078 POSTMASTER: Send address changes or undeliverables to ISI EDGE, 6000 Custer Road, Bldg. 9, Plano, TX 75023 Coaches... RENEW for the NOW PERIODICALS SKATEISI.ORG/PROFESSIONAL It’s renewal time for ISI Professional memberships and liability insurance! Renew your 2019-20 membership at the same time as your insurance and... GET BOTH for one LOW ISI’s insurance benefits are the best in the industry — more coverage at a lower price — plus, ISI policies continue to meet all other association requirements. SKATEISI.ORG/PROFESSIONAL The Professional Journal for the Ice Sports Industry FALL 2019 ISI State of the Union OUR FUTURE IS BRIGHTER THAN EVER! Facility Security Tips Desiccant th Dehumidification 60 Overview CONFERENCE & TRADE SHOW COVERAGE Put the ‘WOW’ in Birthday Parties! SAVE the DATES! The 2020 ISI Conference & Trade Show will take place in two parts of the country. We believe that this new, condensed conference format will be more ISI Spring Conference & Trade Show DFFHVVLEOHWRDQGDRUGDEOH MARCH 23-24 | PASADENA, CA for our members. Hilton Pasadena 168 S Los Robles Ave., Pasadena, CA Group Rate: $179/night WATCH FOR MORE Name: ISI Spring Conference DETAILS COMING SOON! Code: ISI Deadline: March 6 skateisi.org/conference Hotel Amenities: +HDWHGRXWGRRUSRROȴWQHVVFHQWHUDQGFRPSOLPHQWDU\ VKXWWOHVHUYLFHZLWKLQDPLOHUDGLXV On-Ice Education at Pasadena Ice Skating Center 300 E. Green St., Pasadena, CA (Located within walking distance of the hotel.) Conference Attendee Registration Fee Early Bird: Ζ6ΖPHPEHUWKURXJK-DQ QRQPHPEHU ISI Fall Conference & Trade Show NOV. 2-3 | BOSTON, MA Wyndham Boston Beacon Hill %ORVVRP6WUHHW%RVWRQ0$ Group Rate:QLJKW IRUGDWHV2FW1RY Name: ISI Fall Conference Code: C05 Deadline: Oct. -

The Toreador 02 16 1961 (12.66Mb)

Council Arranges Von Braun Talk by Jamie1'UERS by the Student Council, and by Congressman George satellite was orbited only 84 days after von Braun Neil Mc Toreador Stuff \Vrlter Mahon of Lubbock. Mahon had been trying to obtain was given the go-ahead by Defense Secretry von Braun for Tech for some t ime. Elroy on the night ot the Russian launching o! Sput Dr. We von Braun, top U.S. scientist, will The 40-minute convocation will be for Tech stu nik I . speak at an All-CoUege Convocation March 22. dents, faculty members and college representatives Von Brann, according t o the Reader's Digest.. ha.a Von Braun, often proclaimed as the free worl d's only. never yet been \Vrong In any major space predJctloo. ls ector or the George C. l\larshall AuthOr of the book, "First Men to the Moon," a fic lop practical rocket expert and its boldest thinker on Von Braun dir Spnce Agency, center of the U.S. ~lded mJsslle de titious narrathre of the tirst lunar round trip, h e says space travel, will speak at 10 a.m. at the Lubbock ,·etopment a t the U.S. Army's Red.stone Arsenal in that the U.S. should be able to send men to the moon Municipal Auditorium. Huntsville, Aln. and back within 25 year s. "Von Braun's 8pcerh will be o ne of the hlghllr;bts At the age of 20 he was made head of the rocket When asked why men should want to go to the or the year here at Tl"c h, bocause he is the THE man development for the German Army. -

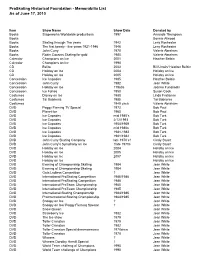

Memorabilia List As of 6-17-10

ProSkating Historical Foundation - Memorabilia List As of June 17, 2010 Item Show Name Show Date Donated by Books Stageworks Worldwide productions 1997 Amanda Thompson Books Bonnie Atwood Books Skating through The years 1942 Leny Rochester Books The first twenty - five years 1921-1946 1946 Leny Rochester Books John Curry 1978 Valerie Abraham Books Robin Cousins Skating for gold 1980 Valerie Abraham Calendar Champions on Ice 2001 Heather Belbin Calendar Champions on Ice 1998 CD Belita 2003 Bill Unwin/ Heather Belbin CD Holiday on Ice 2004 Holiday on Ice CD Holiday on Ice 2005 Holiday on Ice Concession Ice Capades 1985 Heather Belbin Concession John Curry 1982 Jean White Concession Holiday on Ice ?1960s Joanne Funakoshi Concession Ice Follies 1950 Susan Cook Costumes Disney on Ice 1980 Linda Fratianne Costumes Tai Babilonia 1985 Tai Babilonia Costumes 1949 circa Valerie Abraham DVD Peggy Fleming TV Special 1972 Bob Paul DVD Planet Ice 1960 Bob Paul DVD Ice Capades mid 1980’s Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 2/12/1993 Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 1958/1959 Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades mid 1980s Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 1981-1982 Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 1981/1982 Bob Turk DVD John Curry Skating Company late 1970’s? Cindy Stuart DVD John Curry’s Symphony on Ice ?late 1970s Cindy Stuart DVD Holiday on Ice 2004 Holiday on Ice DVD Holiday on Ice 2005 Holiday on Ice DVD Holiday on Ice 2007 Holiday on Ice DVD Holiday on Ice Holiday on Ice DVD Evening of Championship Skating 1984 Jean White DVD Evening of Championship Skating 1984 Jean White DVD Gala Ladiess Competition -

See What's on ¶O – Lelo This Week, This Hour, This Second

FOR THE WEEK OF MAY 28 - JUNE 3, 2017 THE GREAT INDEX TO FUN DINING • ARTS • MUSIC • NIGHTLIFE Look for it every Friday in the HIGHLIGHTS THIS WEEK on Fox. Jamie Foxx hosts this new game show, which TODAY TUESDAY features Shazam, the world’s most popular song identi- The Leftovers World of Dance fication app. HBO 6:00 p.m. KHNL 9:00 p.m. FRIDAY Kevin (Justin Theroux) assumes an alternate identity Extraordinary dancers from all ages and walks of life Shark Tank when he embarks on a mission of mercy in a new epi- kick off the qualifier round for the chance to win a life- sode of “The Leftovers,” airing today on HBO. altering $1-million prize in the premiere of “World of KITV 7:00 p.m. The post-apocalyptic drama follows a family of survi- Dance,” airing Tuesday on NBC. Jenna Dewan Tatum vors a few years after the mysterious simultaneous dis- serves as mentor and host, while Jennifer Lopez, Business moguls decide whether or not to invest appearance of 140 million people. Derek Hough and Ne-Yo serve as judges. their own money in new products and companies in back-to-back episodes of the critically acclaimed reali- ty TV series “Shark Tank,” airing Friday on ABC. MONDAY WEDNESDAY Hopeful entrepreneurs pitch their ideas in the hopes of Lucifer The F Word snagging a deal with a Shark. KHON 8:00 p.m. KHON 8:00 p.m. SATURDAY Charlotte (Tricia Helfer) acciden- Celebrity chef and TV personality Gordon Ram- To Tell the Truth tally charbroils a man to death say hosts as foodie families and friends compete in self-defence, and Lucifer in high-stakes cook-offs in “The F Word,” pre- KITV 7:00 p.m. -

2010-2020 Judgment Updated 10-28-20.Xlsx

Certified Judgment Demand Year Parcel Number Amount Fee Owner Updated 10/28/2020 Address City/State/Zip Reason Date 2020 79-104-55608-20 $315.18 $5.00 10 THOUSAND PERCENT CO COMPLETE NUTRITION 100 S CREASY LN #1220 LAFAYETTE IN 47905 2017 79-130-55608-52 $45.58 $5.00 3 DEZ DESIGNS STEPHANIE FERNANDEZ 4663 E COMMODORES LN LAFAYETTE IN 47909 2010 79-022-70760-13 $65.23 $8.00 4 SONS CUSTOM BUILDERS PO BOX 2736 WEST LAFAYETTE IN 47906 2010 79-022-99643-60 $314.96 $8.00 4 SONS LAWN CARE INC PO BOX 2736 WEST LAFAYETTE IN 47996-2736 2010 79-104-79495-00 $35.28 $8.00 42ND ROYAL HIGHLANDERS INC 2043 S 9TH ST LAFAYETTE IN 47909 2010 79-105-32818-00 $6,647.75 $8.00 A & B DEVELOPMENT LLC EASTSIDE MAGIC SPRAY 98 BOX 5723 LAFAYETTE IN 47903 2012 79-105-32818-00 $15,570.39 $8.00 A & B DEVELOPMENT LLC EASTSIDE MAGIC SPRAY 98 BOX 5723 LAFAYETTE IN 47903 2010 79-127-10978-00 $61.60 $8.00 A & J SIGNS ANDREW CORBIN 5306 N COUNTY LINE RD E LAFAYETTE IN 47905 PAID IN FULL 7/11/2011 2010 79-104-28604-00 $67,640.46 $8.00 A & K CONSTRUCTION INC 540 MORLAND DR LAFAYETTE IN 47905 2012 79-104-28604-00 $57,729.43 $8.00 A & K CONSTRUCTION INC 540 MORLAND DR LAFAYETTE IN 47905 2012 79-004-67386-45 $107.86 $8.00 A 1 REAL ESTATE INSPECTION UNIT A 659 N 36TH ST LAFAYETTE IN 47905 2013 79-004-67386-45 $32.00 $8.00 A 1 REAL ESTATE INSPECTION A1 REAL ESTATE INSPECTION 2616 SOUTH RIVER RD WEST LAFAYETTE IN 47906 2014 79-004-67386-45 $32.00 $5.00 A 1 REAL ESTATE INSPECTION A1 REAL ESTATE INSPECTION 2616 SOUTH RIVER RD WEST LAFAYETTE IN 47906 2010 79-007-59378-54 $27.22 $8.00 -

Champions of the United States

U.S. FIGURE SKATING DIRECTORY CHAMPIONS OF THE UNITED STATES LADIES 1960 Carol Heiss, The SC of New York 2018 Nathan Chen, Salt Lake Figure Skating 1959 Carol Heiss, The SC of New York 2017 Nathan Chen, Salt Lake Figure Skating 2021 Bradie Tennell, Skokie Valley SC 1958 Carol Heiss, The SC of New York 2016 Adam Rippon, The SC of New York 2020 Alysa Liu, St. Moritz ISC 1957 Carol Heiss, The SC of New York 2015 Jason Brown, Skokie Valley SC 2019 Alysa Liu, St. Moritz ISC 1956 Tenley Albright, The SC of Boston 2014 Jeremy Abbott, Detroit SC 2018 Bradie Tennell, Skokie Valley SC 2013 Max Aaron, Broadmoor SC 2017 Karen Chen, Peninsula SC 1955 Tenley Albright, The SC of Boston 1954 Tenley Albright, The SC of Boston 2012 Jeremy Abbott, Detroit SC 2016 Gracie Gold, Wagon Wheel FSC 2011 Ryan Bradley, Broadmoor SC 1953 Tenley Albright, The SC of Boston 2015 Ashley Wagner, SC of Wilmington 2010 Jeremy Abbott, Detroit SC 1952 Tenley Albright, The SC of Boston 2014 Gracie Gold, Wagon Wheel FSC 2009 Jeremy Abbott, Broadmoor SC 1951 Sonya Klopfer, Junior SC of New York 2013 Ashley Wagner, SC of Wilmington 2008 Evan Lysacek, DuPage FSC 1950 Yvonne Sherman, The SC of New York 2012 Ashley Wagner, SC of Wilmington 2007 Evan Lysacek, DuPage FSC 1949 Yvonne Sherman, The SC of New York 2011 Alissa Czisny, Detroit SC 2006 Johnny Weir, The SC of New York 1948 Gretchen Merrill, The SC of Boston 2010 Rachael Flatt, Broadmoor SC 2005 Johnny Weir, The SC of New York 2009 Alissa Czisny, Detroit SC 1947 Gretchen Merrill, The SC of Boston 2004 Johnny Weir, The SC of New York 2008 Mirai Nagasu, Pasadena FSC 1946 Gretchen Merrill, The SC of Boston 2003 Michael Weiss, Washington FSC 2007 Kimmie Meissner, Univ. -

December 2017 Sad News Gerry Willis – November 2017

REUNION EDITION NEWS FROM ICE CAPADES ALUMNI December 2017 Sad News Gerry Willis – November 2017 For those who knew Gerry Willis I see on his wife Helga's page that Gerry has recently passed away in England. I worked with him and Helga in Ice Capades West Co., 1976 tour. He was always nice to everyone and was a lot of fun. Sashi, Gerry, Helga & Ann-Margreth at Halloween Party. Our Alumni in the News Skating champion Karen Magnussen warns about ammonia gas leaks at ice arenas Magnussen, 65, said the deaths of three men in Fernie, British Columbia, after an ammonia leak at the local arena is a horrible tragedy and she urged communities across Canada to ensure arena cooling systems are regularly maintained and inspected. Dirk Meissner, The Canadian Press Published Saturday, October 21, 2017 7:39AM EDT Last Updated Saturday, October 21, 2017 11:57AM EDT Canadian Olympic silver medallist and former world champion figure skater Karen Magnussen can still feel the spot deep in her chest where an ammonia leak burned her lungs six years ago, leaving her disabled and unable to go back to an ice rink to teach the sport she loves. Magnussen, 65, said the deaths of three men this week in Fernie, British Columbia, after an ammonia leak at the local arena is a horrible tragedy and she urged communities across Canada to ensure arena cooling systems are regularly maintained and inspected. "We're talking about children," she said in a telephone interview from her home in Langley, B.C. "Not to mention all the people who are there watching. -

Daphne Maxwell Reid and Other Creators Whose Work Lifts Us

May 2020 | soulvisionmagazine.com EDITORS NOTE BK Fulton Photo by Queon “Q” Martin “. explore the little things in life and the big ones too.” Our May issue is dedicated to those who inspire. We feature Tai Babilonia, Kelcey Mawema, Rolonda Wright, Daphne Maxwell Reid and other creators whose work lifts us. We also were fortunate to spend this month with the amazing Adriana Trigiani – author, director, historian . and renaissance woman! Adriana graces our May cover because she is an example of the best of us and yet she remains as humble as her origins. Big Stone Gap, also the name of her first movie, is Adriana’s hometown where she grew up with grace and the support of her family. It was there that she explored the little things in life and the big ones too. Reading and learning were the driving forces behind her creativity. She thought she was going to be a poet until telling stories as an author became her passion. I was so moved by our interview with Adriana, that I wrote a poem in her honor (see below). Thank you, Adriana and all of our guests for this issue of SoulVision Magazine. You get a new look when you have SoulVision. 2 May 2020 | soulvisionmagazine.com BK Fulton - May 2020 (contiuned) A Light of the World Raised right and beautiful too . the world is better because of you! Keep on doing the things that you do; don’t let the naysayers say when you’re through. Make them learn as much as you teach . you are changing our nation and the world is in reach! Remember the babies; it’s about them not us. -

February 15, 1961 (Wednesday)

February 13, 1961 (Monday) The Congo government announces the death of Patrice Lumumba, without taking responsibility for his execution. February 14, 1961 (Tuesday) Discovery of the chemical elements: Element 103, Lawrencium, is first synthesized in Berkeley, California. February 15, 1961 (Wednesday) A total solar eclipse is visible in parts of the Northern Hemisphere. President John F. Kennedy warns the Soviet Union to avoid interfering with the United Nations pacification of the Congo. Sabena Flight 548 crashes near Brussels, Belgium, killing 73 people, including all 18 members of the United States figure skating team and several coaches. Died in the crash of Sabena Flight 548: Maribel Vinson, 49, nine-time US national figure skating champion, and her two daughters: Laurence Owen, 16, US national ladies' singles champion, and Maribel Owen, 20, US national pairs champion; Dudley Richards, 29 Maribel Owen's pairs partner; Dona Lee Carrier, 20, and her ice dance partner Roger Campbell, 19; Patricia Dineen, 25, and her husband and ice dance partner Robert Dineen, 25; Ray Hadley, Jr., 17, and his sister Ila Ray Hadley, 18, ice dance competitors; Harold Hartshorne, 69, skating judge and former ice dancer; Laurie Hickox, 15, and her brother and pairs partner William Hickox, 19; Gregory Kelley, 16, US junior men's singles champion; Edward LeMaire, skating judge, and his 14-year-old son; Bradley Lord, 21, US men's singles champion; Rhode Lee Michelson, 17, ladies' singles competitor; Douglas Ramsay, 16, men's singles competitor; Edi Scholdan, Austrian figure skater and coach, and his 13-year-old son; Diane Sherbloom, 18, and her ice dance partner Larry Pierce, 24; Stephanie Westerfeld, 17, ladies' singles competitor; February 16, 1961 (Thursday) Cyprus's first nationality law is enacted. -

Be Square Caller’S Handbook

TAble of Contents Introduction p. 3 Caller’s Workshops and Weekends p. 4 Resources: Articles, Videos, etc p. 5 Bill Martin’s Teaching Tips p. 6 How to Start a Scene p. 8 American Set Dance Timeline of Trends p. 10 What to Call It p. 12 Where People Dance(d) p. 12 A Way to Begin an Evening p. 13 How to Choreograph an Evening (Programming) p. 14 Politics of Square Dance p. 15 Non-White Past, Present, Future p. 17 Squeer Danz p. 19 Patriarchy p. 20 Debby’s Downers p. 21 City Dance p. 22 Traveling, Money, & Venues p. 23 Old Time Music and Working with Bands p. 25 Square Dance Types and Terminology p. 26 Small Sets p. 27 Break Figures p. 42 Introduction Welcome to the Dare To Be Square Caller’s handbook. You may be curious about starting or resuscitating social music and dance culture in your area. Read this to gain some context about different types of square dancing, bits of history, and some ideas for it’s future. The main purpose of the book is to show basic figures, calling techniques, and dance event organizing tips to begin or further your journey as a caller. You may not be particularly interested in calling, you might just want to play dance music or dance more regularly. The hard truth is that if you want trad squares in your area, with few ex- ceptions, someone will have to learn to call. There are few active callers and even fewer surviving or revival square dances out there. -

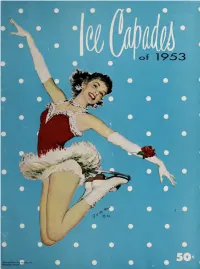

Ice Capades of 1953 Program

Copyright 1952— lc» CopodM, Inc. World Rights Reserved . Entire Production Iced By JOHN H. HARRIS Choreography by CHESTER HALE, JOHN BUTLER, ROSEMARIE STEWART and ROBERT DENCH Costumes designed by BILLY LIVINGSTON Scenery and properties designed by RICHARD N. JACKSON All costumes, scenery and properties built in Ice Capades Prop and Costume Shop 9268 West Third Street, Beverly Hills, California Costumes executed by MADAME CELINE FAUR Props and scenery by FLOYD PARRISH Musical score by JERI MAYHALL Assisted by FRAN FREY Photography by BRADLEY SMITH STAFF Brian McDonald . Company Manager Denise Benoit Public Relations William McLoughlln Business Manager Dan Brown Lighting Director Howard Price .... Company Treasurer Jeyne Brown Secretary Note Walley .... Performance Director Freddie Thibideaux Stage Manager Rosemarie Stewart Production Coordinator Gearge Frey Master Electrician Robert Dench .... Production Coordinator John Connors Master of Properties Jeri Mayhall Musical Director Ray Currel Assistant Electrician Aaron Beiner .... Assistant Director Robert Costello Assistant Carpenter Henry Barnicle . Percussionist Robert Bingham Skate Technician Morgaiet Schriner. .Registered Nurse & Chaperone Robert Skrak Ice Technician Gladys Algiere . Wardrobe Mistress Leo Loeb Baggage & Concession Supervisor Melvin Lyall Wardrobe Master Harry Hasley Advance Technician Lillian Bustin Ass't Wardrobe Mistress Patricia Matthews Captain of Ca"p6*s" William Dougherty Captain of Cadets Elena Brown Captain of Ca"pets" John Gaudreault . Captain of Cadets Barbara Lange Dyke Captain of Ca"pets" CALIFORNIA OFFICE Walter Good Prop. & Costume Shop General Manager Floyd Parrish Prop. Shop Manager Cliff Lewis Advertising Director William Delany Prop. & Costume Shop Buyer Celine Four Costume Shop Henry Weiss Costume Shop Manager CHICAGO OFFICE Marshall Alderson Transportation Manager ICE CAPADES, INC., 6121 Santa Monica Blvd., Hollywood, California NORMAN FRESCOTT, General Manager JOHN H. -

Las Vegas, Nevada

2021 Toyota U.S. Figure Skating Championships January 11-21, 2021 Las Vegas | The Orleans Arena Media Information and Story Ideas The U.S. Figure Skating Championships, held annually since 1914, is the nation’s most prestigious figure skating event. The competition crowns U.S. champions in ladies, men’s, pairs and ice dance at the senior and junior levels. The 2021 U.S. Championships will serve as the final qualifying event prior to selecting and announcing the U.S. World Figure Skating Team that will represent Team USA at the ISU World Figure Skating Championships in Stockholm. The marquee event was relocated from San Jose, California, to Las Vegas late in the fall due to COVID-19 considerations. San Jose meanwhile was awarded the 2023 Toyota U.S. Championships, marking the fourth time that the city will host the event. Competition and practice for the junior and Championship competitions will be held at The Orleans Arena in Las Vegas. The event will take place in a bubble format with no spectators. Las Vegas, Nevada This is the first time the U.S. Championships will be held in Las Vegas. The entertainment capital of the world most recently hosted 2020 Guaranteed Rate Skate America and 2019 Skate America presented by American Cruise Lines. The Orleans Arena The Orleans Arena is one of the nation’s leading mid-size arenas. It is located at The Orleans Hotel and Casino and is operated by Coast Casinos, a subsidiary of Boyd Gaming Corporation. The arena is the home to the Vegas Rollers of World Team Tennis since 2019, and plays host to concerts, sporting events and NCAA Tournaments.