Routes and Roots FINAL TEXT.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Bands of the 60S & 70S | Sample Answer

Irish Bands of the 60s & 70s | Sample answer Ceoltóiri Cualann was an Irish group formed by Sean O’Riada in 1961. O’Riada had the idea of forming Ceoltóiri Cualann following the success of a group he had put together to perform music for the play “The Song of the Anvil” in 1960. Ceoltóiri Cualann would be a group to play Irish traditional songs with accompaniment and traditional dance tunes and slow airs. All folk music recorded before that time had been highly orchestrated and done in a classical way. Another aim of O’Riada’s was to revitalise the work of harpist and composer Turlough O’Carolan. Ceoltóiri Cualann was launched during a festival in Dublin in 1960 at an event called Recaireacht an Riadaigh and was an immediate success in Dublin. The group mainly played the music of O’Carolan, sean nós style songs and Irish traditional tunes, and O’Riada introduced the bodhrán as a percussion instrument. Ceoltóiri Cualann had ceased playing with any regularity by 1969 but reunited to record “O’Riada” and “O’Riada Sa Gaiety” that year. “O’Riada Sa Gaiety” was not released until after O’Riada’s death in 1971. The members of Ceoltóiri Cualann, some of whom went on to form “The Chieftains” in 1963 were O’Riada (harpsichord and bodhrán), Martin Fay, John Kelly (both fiddle), Paddy Moloney (uilleann pipes), Michael Turbidy (flute), Sonny Brogan, Éamon de Buitléir (both accordian), Ronnie Mc Shane (bones), Peadar Mercer (bodhrán), Seán Ó Sé (tenor voice) and Darach Ó Cathain (sean nós singer. Some examples of their tunes are “O’ Carolan’s Concerto” and “Planxty Irwin”. -

Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 3-1995 Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music Matthew S. Emmick Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Emmick, Matthew S., "Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music" (1995). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 21. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/21 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM Honors Thesis Certification Matthew S. Emmick Applicant (Name as It Is to appear on dtplomo) Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle M'-Isic Thesis title _ May, 1995 lnter'lded date of commencemenf _ Read and approved by: ' -4~, <~ /~.~~ Thesis adviser(s)/ /,J _ 3-,;13- [.> Date / / - ( /'--/----- --",,-..- Commltte~ ;'h~"'h=j.R C~.16b Honors t-,\- t'- ~/ Flrst~ ~ Date Second Reader Date Accepied and certified: JU).adr/tJ, _ 2111c<vt) Director DiJe For Honors Program use: Level of Honors conferred: University Magna Cum Laude Departmental Honors in Music and High Honors in Spanish Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music A Thesis Presented to the Departmt!nt of Music Jordan College of Fine Arts and The Committee on Honors Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Matthew S. Emmick March, 24, 1995 -l _ -- -"-".,---. -

Jordi Savall and Carlos Núñez and Friends Thursday, May 10, 2018 at 8:00Pm This Is the 834Thconcert in Koerner Hall

Jordi Savall and Carlos Núñez and Friends Thursday, May 10, 2018 at 8:00pm This is the 834thconcert in Koerner Hall Carlos Núñez, Galician bagpipes, pastoral pipes (Baroque ancestor of the Irish Uilleann pipes) & whistles Pancho Álvarez, Viola Caipira (Brazilian guitar of Baroque origin) Xurxo Núñez, percussions, tambourins & Galician pandeiros Andrew Lawrence-King, Irish harp & psalterium Frank McGuire, bodhran Jordi Savall, treble viol (by Nicholas Chapuis, Paris c. 1750) lyra-viol (bass viol by Pelegrino Zanetti, Venice 1553) & direction PROGRAM – CELTIC UNIVERSE Introduction: Air for the Bagpipes The Caledonia Set Traditional Irish: Archibald MacDonald of Keppoch Traditional Irish: The Musical Priest / Scotch Mary Captain Simon Fraser (1816 Collection): Caledonia's Wail for Niel Gow Traditional Irish: Sackow's Jig Celtic Universe in Galicia Alalá En Querer Maruxiña Diferencias sobre la Gayta The Lord Moira Set Dan R. MacDonald: Abergeldie Castle Strathspey Traditional Scottish: Regents Rant - Lord Moira Ryan’s Mammoth Collection (Boston, 1883): Lord Moira's Hornpipe Flowers of Edinburg Charlie Hunter: The Hills of Lorne Reel: The Flowers of Edinburg Niel Gow: Lament for the Death of his Second Wife Fisher’s Hornpipe Tomas Anderson: Peter’s Peerie Boat INTERMISSION The Donegal Set Traditional Irish: The Tuttle’s Reel Traditional Scottish: Lady Mary Hay’s Scots Measure Turlough O’Carolan: Carolan’s Farewell Donegal tradition: Gusty’s Frolics Jimmy Holme’s Favorite Carolan’s Harp Anonymous Irish: Try if it is in Tune: Feeghan Geleash -

CA Activities Update - January 18, 2014

CA Activities Update - January 18, 2014 Lifestyle Department January 18, 2014 Click here to access the CA Activities Calendar Onsite • The Studebakers, January 22, 6 - 8 p.m., SCB, $11 • Red Alert – Rock N Roll Dance, January 24, 7 - 10 p.m., $11 pp • Mars Curiosity: Amazing Mission, January 28, 1 p.m., SCB, $5 pp Outings • 3 Laps in a Lamborghini, February 21, $172 pp • "Spurs Nation" Basketball, February 26, $100 pp • Celtic Music - The Chieftains at The Riverbend Centre, February 26, $92 pp • The Olympics of the Violin & Dinner at BRIO, Saturday, March 1, $110 pp Extended Travel • The Gardens of London • New York City • Canadian Rockies by Train • Royal Caribbean Alaska Cruise Tour • Scenic Switzerland by Train • Trains of the Colorado Rockies • Colorado Springs Getaway • Fall Foliage Cruise Onsite The Studebakers – Performance Wednesday, January 22, 6 - 8 p.m., SCB, $11 Open Seating Cabaret Style Harmonizing since 1993, The Studebakers are influenced by The Andrews Sisters, The Boswell Sister, The Chenille Sister, Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey and The Manhattan Transfer. Jill Montgomery started the group, wanting to bring back the marvelous melodies and lyrics of the songs from the ’20s, ’30s and ’40s and deliver them with the clarity and close harmony that made them such big favorites. The band consists of five members: Jill Montgomery, Becky Cavanaugh and Sharon Maner are the core trio, singing tunes made famous by the Andrews Sisters and Boswell Sisters among others; Randy Seybold plays virtuoso bass and guitar and sings baritone; and Marilyn Rucker joins in on keyboards and vocals. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 119, 1999-2000

O Z A W A Dl R ECTOR BOSTON ^SYMPHONY # E S T R A M 1 i! kff^^f y-^fflfe 1 ^WVIi 19 9 9-2000 SEASON Bring your Steinway: With floor plans from acre gated community atop 2,100 to 5,000 square feet, prestigious Fisher Hill. you can bring your Concert Jointly marketed by Sotheby's Grand to Longyear. International Realty and You'll be enjoying full-service, Hammond Residential Real Estate. single-floor condominium living at Priced from $1,200,000. its absolutefinest, all harmoniously Call Hammond Real Estate at located on an extraordinary eight- (617) 731-4644, ext 410. LONGYEAR, a/ Lr/sner Jiili BROOKLINE pssf^te. "-J ' jjmgr^^8PL'ti n-^a >/:i LlEii'••*' ^^ ^^^v SSi^Ty^f-vg^^i^fe jSP&^j : HE^Sg^^ • .^^^^.*y£^\&?* .TV ,.->< VH) 11. |1»W mm DBD CORTLAND Hammond SOTHEBYSI PROPERTIES INC. RESIDENTIAL International Realty Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Nineteenth Season, 1999-2000 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson Deborah B. Davis George Krupp Robert P. O'Block Diane M. Austin, Nina L. Doggett Ed Linde ex-ojficio ex-ojficio Nancy J. Fitzpatrick R. Willis Leith, Jr. Peter C. Read Gabriella Beranek Charles K. Gifford Mrs. August R. Meyer Hannah H. Schneider Jan Brett Avram J. Goldberg Richard P. Morse Thomas G. Sternberg James F. Cleary Thelma E. -

The Chieftains

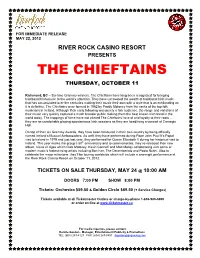

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MAY 22, 2012 RIVER ROCK CASINO RESORT PRESENTS THE CHIEFTAINS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 11 Richmond, BC – Six-time Grammy winners, The Chieftains have long been recognized for bringing traditional Irish music to the world’s attention. They have uncovered the wealth of traditional Irish music that has accumulated over the centuries making their music their own with a style that is as exhilarating as it is definitive. The Chieftains were formed in 1962 by Paddy Moloney from the ranks of the top folk musicians in Ireland. Although their early following was purely a folk audience, the range and variations of their music very quickly captured a much broader public making them the best known Irish band in the world today. The trappings of fame have not altered The Chieftains’ love of and loyalty to their roots … they are as comfortable playing spontaneous Irish sessions as they are headlining a concert at Carnegie Hall. On top of their six Grammy Awards, they have been honoured in their own country by being officially named Ireland’s Musical Ambassadors. As well, they have performed during Pope John Paul II’s Papal visit to Ireland in 1979 and just last year, they performed for Queen Elizabeth II during her historical visit to Ireland. This year marks the group’s 50th anniversary and to commemorate, they’ve released their new album, Voice of Ages which finds Moloney, Kevin Conneff and Matt Molloy collaborating with some of modern music’s fastest rising artists including Bon Iver, The Decemberists and Paolo Nutini. Also to celebrate the major milestone, they’ll be touring worldwide which will include a one-night performance at the River Rock Casino Resort on October 11, 2012. -

October 1982 Crgnsas (Itts Music Ani 'F.Jntertainment ~Wsfafer Issue 22 · Hac · , Chieftains to Th E Irl~ Re Omlng

BULK RATE u.s. POSTAGE PAID Permit No. 2419 K.C.,MO ;~~KC PITCtI FREE October 1982 CRgnsas (itts Music ani 'f.Jntertainment ~wsfafer Issue 22 · hAC · , Chieftains to Th e Irl~ re omlng. View Stockyards? Bijou & Fine Arts Calendars .................. p. 8, 9,10 Beyond the Beaver ...................... p.ll Juvenile Delinquency Film Festival ...................... p.ll Hollywood Hoopla inKC The Chieftains. Seated are Dereck Bell and Paddll;MQlQ~"~~•• will plQY at The Lyric Theater October 20. Blue Riddim Band ,~...... .J __ ~0m,Qjj~~IH.:!la:!JSH~df Westport and through Rockhurst College Ticket Information Center, 926-4127. by DWight Frizzell Stones on more than one occasion during the Chieftains play, an audience that broke A Sunsplash Smash their last tour. At the historic concert at Slain all pr~vious attendance records set by the Castle in Dublin, Kevin Conneff presented Rolling Stones, the Beatles and the Bee Willi Me What Irish group has performed with the Rolling Stones drummer Charley Watts with Gees. Paddy Maloney modestly told the Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney and a a bodhran. What followed was an impromp Pitch, "It wasn't our gig. The Pope was the Chinese tradition music ensemble, has work Montego Bay, Jamaica. Kansas City's tu jam backstage, after which Watts promis headliner." ed with Stanley Kubrick, holds the world own reggae aficionados, The Blue Riddim ed that he would play the bodhran on at least The Chieftains achieved yet another first record for playing before the largest live au Band, did their bit to ensure themselves a when they played with a traditional Chinese dience, performed for Pope John Paul II and page in musical history. -

Playnetwork Business Mixes

PlayNetwork Business Mixes 50s to Early 60s Marketing Strategy: Period themes, burgers and brews and pizza, bars, happy hour Era: Classic Compatible Music Styles: Fun-Time Oldies, Classic Description: All tempos and styles that had hits Rock, 70s Mix during the heyday of the 50s and into the early 60s, including some country as well Representative Artists: Elvis, Fats Domino, Steve 70s Mix Lawrence, Brenda Lee, Dinah Washington, Frankie Era: 70s Valli and the Four Seasons, Chubby Checker, The Impressions Description: An 8-track flashback of great music Appeal: People who can remember and appreciate from the 70s designed to inspire memories for the major musical moments from this era everyone. Featuring hits and historically significant album cuts from the “Far Out!,” Bob Newhart, Sanford Feel: All tempos and Son era Marketing Strategy: Hamburger/soda fountain– Representative Artists: The Eagles, Elton John, themed cafes, period-themed establishments, bars, Stevie Wonder, Jackson Brown, Gerry Rafferty, pizza establishments and clothing stores Chicago, Doobie Brothers, Brothers Johnson, Alan Parsons Project, Jim Croce, Joni Mitchell, Sugarloaf, Compatible Music Styles: Jukebox classics, Donut Steely Dan, Earth Wind & Fire, Paul Simon, Crosby, House Jukebox, Fun-Time Oldies, Innocent 40s, 50s, Stills, and Nash, Creedence Clearwater Revival, 60s Average White Band, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Electric Light Orchestra, Fleetwood Mac, Guess Who, 60s to Early 70s Billy Joel, Jefferson Starship, Steve Miller Band, Carly Simon, KC & the Sunshine Band, Van Morrison Era: Classic Feel: A warm blanket of familiar music that helped Description: Good-time pop and rock legends from define the analog sound of the 70s—including the the mid-60s through the early-to-mid-70s that marked one-hit wonders and the best known singer- the end of an era. -

Press Release

BOSTON’S ERIN OG Website: www.bostonserinog.com Email: [email protected] Facebook: www.facebook.com/erin.og1 Bobby Mullis Dave McGrath Steve Maher Vocal/Whistles Guitar/Vocal Fiddle/Vocal BIOGRAPHY Boston’s Erin Og has united the best of Boston's Irish music scene, mixing fiddle, tin whistle, driving acoustic guitar and powerful vocal harmonies—a verita- ble tour-de-force of Irish Folk music. BEO has covered a lot of ground, traveling the length of the USA. Featured in an episode of the inter- national hit TV show "Ghost Hunter's" in Paddy Reilly's in Manhattan to an eight gig stint in "Ri Ra Mandalay Bay" Las Vegas. BEO continues it's foray into New York City and all over New England. BEO's rollicking performance and soulful ballads should not be missed. They draw the audience in and make everyone a part of the band. Press and Reviews “The three teamed up in Boston where they worked together to hone their passionate ballad singing and master their strong sound that is reminiscent of the days of the great Irish balladeers.” Liz Noonan, Irish Echo—Sept. 4, 2012 “One of the true joys of listening to Celtic music is the opportunity of coming across new tracks... From the very first notes on, we are treated to an earnest and authentic presentation delivered with the kind of authority we'd expect from Irish masters the likes of the Clancy's, and the Chieftains.” Gene Ira Katz.. “You guys were amazing last night at the Bloody Sunday event! Thank you so much for being a part of this special occasion. -

Eileen Ivers Biography

Biography Eileen Ivers Biography Nine Time All-Ireland Fiddle Eileen Ivers & Immigrant Soul Champion Beyond the Bog Road Riverdance An Nollaig - An Irish Christmas The Chieftains Grammy Awarded Musician Sting Boston Pops Hall & Oates London Symphony Orchestra Afrocelts Cleveland Orchestra Patti Smith, Paula Cole, Steve Gadd, National Symphony Orchestra Al Di Meola, Terence Blanchard... Guest Star with over 40 Symphony Founding member of Cherish the Orchestras Ladies Eileen Ivers will change the way you think about the violin. Eileen Ivers & Immigrant Soul, Nine Time All-Ireland Fiddle Champion, London Symphony Orchestra, National Symphony at The Kennedy Center, Boston Pops, original musical star of Riverdance, The Chieftains, Sting, Hall & Oates, Afrocelts, Patti Smith, Paula Cole, Al Di Meola, Steve Gadd, founding member of Cherish the Ladies, Grammy awarded musician, performed for Presidents and Royalty worldwide…this is a short list of accomplishments, headliners, tours, and affiliations. Fiddler Eileen Ivers has established herself as the pre-eminent exponent of the Irish fiddle in the world today. It is a rare and select grade of spectacular artists whose work is so boldly imaginative and clearly virtuosic that it alters the medium. It has been said that the task of respectfully exploring the traditions and progression of the Celtic fiddle is quite literally on Eileen Ivers' shoulders. The Washington Post states, "She suggests the future of the Celtic fiddle." She's been called a "sensation" by Billboard magazine and "the Jimi Hendrix of the violin" by The New York Times. "She electrifies the crowd with a dazzling show of virtuoso playing" says The Irish Times. -

JANINE REDMOND : Button Accordion MICHAEL HARRISON

FULLSET PERFORMER BIOS JANINE REDMOND : Button Accordion Janine Redmond, native to Dublin, is one of Ireland’s most dynamic young button accordion players. Under the tuition of Sligo born John Regan and well-known flute player June McCormack, she has achieved numerous solo All-Ireland titles in both accordion and melodeon. Having graduated from St. Patrick’s College of Education in Irish and Music she has attained a rich traditional style influenced by luminaries such as Joe Burke. Janine has also toured extensively throughout America, Latvia, China, Japan, Poland, France and Australia. She has performed with the renowned music and dance group Brú Ború in Cashel, Co. Tipperary and was also a featured artist on RTÉ’s Bloom of Youth programme in 2008. MICHAEL STRIBLING: Uilleann Pipes, Whistles Michael Stribling is an award winning uilleann piper and traditional Irish musician who hails from sunny Florida. He studied under master Irish musicians including Jerry O'Sullivan, Mickey Dunne, Joannie Madden, and Catherine McEvoy. Michael won the title of All Ireland Champion on the uilleann pipes when he competed in the 2010 Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann in Cavan, Ireland. He has toured and performed across the United States, Canada, and Europe with Irish Music groups such as FullSet, Runa and Killavil. His dedication to the tradition shines through on his work with the uilleann pipes, low whistle, flute, and tin whistle. He is a founding member of the Irish group Killavil which he performs with actively across the USA and abroad. MICHAEL HARRISON : Fiddle Tipperary man, Michael Harrison, a grandson of well-known fiddle player Aggie Whyte, is at the forefront of young Irish fiddle players. -

SPECIAL MUSICAL PERFORMANCE SHARON SHANNON Irish Button Accordion Musician ______

SPECIAL MUSICAL PERFORMANCE SHARON SHANNON Irish Button Accordion Musician _________________________________________________ Sharon Shannon the button accordion player from Co Clare, Ireland has recorded and toured with a who's who of the Irish and Global Music Industry, including Bono, Adam Clayton, Sinead O’Connor, Jackson Browne, John Prine, Steve Earle, The RTE Concert Orchestra, The Chieftains, The Waterboys, Willie Nelson, Nigel Kennedy, Alison Krauss and Shane MacGowan. Her 12 studio recorded albums to date have all been very different and groundbreaking mixing traditional Irish with reggae, country, Native American, bluegrass, rap, dance, African, French Canadian. The genre-defying star has had multi-platinum album sales and has had several number one albums, singles and DVDs in her home country. Her album Galway Girl went 4 times platinum in Ireland with the title track winning her the Meteor award two years running for the most downloaded song. However, her career took a massive upward trajectory when in the late 80s she was asked to joined the seminal rock band The Waterboys. Her first show with that band, to an audience of 50,000, was the on main stage at perhaps the most well-known music festival on earth- Glastonbury. Her subsequent debut album was released worldwide and was to become the biggest selling record by a traditional artiste in Ireland. She has entertained US Presidents Clinton at the White House and Obama in Dublin and Irish Presidents Robinson and MacAleese on presidential visits to Poland and Australia respectively. She recently accompanied Irish president Michael D. Higgins on his official tour of China.