To Regulate Or Not to Regulate:Current Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

IN the COURT of CRIMINAL APPEALS of TENNESSEE at KNOXVILLE October 25, 2005 Session

IN THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS OF TENNESSEE AT KNOXVILLE October 25, 2005 Session STATE OF TENNESSEE v. JANIS SUE WATSON AND ALBERT EUGENE BROOKS Direct Appeal from the Criminal Court for Hamblen County No. 03CR297 James E. Beckner, Judge No. E2004-02145-CCA-R3-CD - Filed March 20, 2006 Janis Sue Watson and Albert Eugene Brooks, the co-defendants, were convicted of first degree premeditated murder and conspiracy to commit first degree murder, a Class A felony. Each co- defendant received concurrent sentences of life in prison and twenty years, respectively. The co- defendants’ consolidated appeals address both the convictions and sentences. Having found no reversible error, the convictions and sentences of both co-defendants are affirmed. Tenn. R. App. P. 3 Appeal as of Right; Judgments of the Criminal Court Affirmed JOHN EVERETT WILLIAMS, J., delivered the opinion of the court, in which GARY R. WADE, P.J., and JOSEPH M. TIPTON, J., joined. Greg Eichelman, District Public Defender, and Clifton Barnes, Assistant Public Defender, for the appellant, Janis Sue Watson. Douglas L. Payne and Lewis Ricker, Greeneville, Tennessee, for the appellant, Albert Eugene Brooks. Paul G. Summers, Attorney General and Reporter; Renee W. Turner, Assistant Attorney General; William Paul Phillips, District Attorney General; and Jared Effler, Assistant District Attorney General, for the appellee, State of Tennessee. OPINION The history of this case began with the co-defendants, Janis Sue Watson and Albert Eugene Brooks, becoming acquainted through an internet co-dependency support group. The co-defendants’ relationship deepened, and they eventually met and became intimate. Their relationship came under scrutiny when defendant Watson’s husband, Larry Watson, was murdered in the Watsons’ Morristown home on October 30, 2002. -

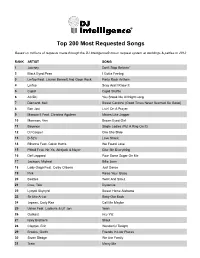

Most Requested Songs of 2012

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2012 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 3 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 8 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 9 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 10 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 11 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 B-52's Love Shack 14 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 15 Pitbull Feat. Ne-Yo, Afrojack & Nayer Give Me Everything 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 18 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 19 Pink Raise Your Glass 20 Beatles Twist And Shout 21 Cruz, Taio Dynamite 22 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 23 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 24 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 25 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 26 Outkast Hey Ya! 27 Isley Brothers Shout 28 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 29 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 30 Sister Sledge We Are Family 31 Train Marry Me 32 Kool & The Gang Celebration 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Temptations My Girl 35 ABBA Dancing Queen 36 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 37 Flo Rida Good Feeling 38 Perry, Katy Firework 39 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 40 Jackson, Michael Thriller 41 James, Etta At Last 42 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 43 Lopez, Jennifer Feat. -

Memorandum Waiving Prohibition on United States Military Assistance to Parties to the Rome Statute Establishing the Internationa

1522 Nov. 1 / Administration of George W. Bush, 2003 never forget the lessons of September the Memorandum Waiving Prohibition 11th, 2001. We must understand we have a on United States Military Assistance duty and responsibility to provide security for to Parties to the Rome Statute the people of this country. Therapy is not Establishing the International going to work with that bunch. [Laughter] Criminal Court We must be smart. We must be tough. We November 1, 2003 will not tire. We will not rest until this danger to civilization is removed. Presidential Determination No. 2004–07 When I came into office, morale in the Memorandum for the Secretary of State U.S. military was beginning to suffer, so we Subject: Waiving Prohibition on United increased the defense budget. Ernie Fletcher States Military Assistance to Parties to the stood right by my side, making sure our Rome Statute Establishing the International troops, our brave troops, got the best train- Criminal Court ing, the best pay, and the best possible equip- ment. Consistent with the authority vested in me by section 2007 of the American But I want you to know, the best way to Servicemembers’ Protection Act of 2002 (the safeguard America is to work to spread free- ‘‘Act’’), title II of Public Law 107–206 (22 dom, is to make sure that freedom can take U.S.C. 7421 et seq.), I hereby determine that: hold around the world. See, free societies Antigua and Barbuda, Botswana, East don’t attack their neighbors. Free societies Timor, Ghana, Malawi, Nigeria, and Uganda do not develop weapons of mass terror to have each entered into an agreement with blackmail or threaten the world. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Student Dropout from the Perspectives of Junior High Counselors in Northeast Mississippi

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Student Dropout From The Perspectives Of Junior High Counselors In Northeast Mississippi Kelly Ann Bennett University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Elementary Education Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Kelly Ann, "Student Dropout From The Perspectives Of Junior High Counselors In Northeast Mississippi" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 475. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/475 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT DROPOUT FROM THE PERSPECTIVES OF JUNIOR HIGH COUNSELORS IN NORTHEAST MISSISSIPPI A Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in the Department of Teacher Education The University of Mississippi by KELLY ANN BENNETT December 2013 Copyright Kelly Ann Bennett 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT I investigated fifteen junior high counselors’ understandings about student dropout, particularly about identification of and interventions for students at risk for dropping out of school. As an educator, I desired to research the phenomenon of student dropout to understand how to better reach these types of students. Research is available concerning student dropout from the perspectives of teachers, principals, and student dropouts; however, little research on student dropout from the viewpoint of counselors exists. I utilized a qualitative design, in particular a descriptive case study, to develop understanding of the counselors’ perspectives of student dropout. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Right by My Side ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Right by My Side ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS THE AUTHOR THANKS the following for their assistance in the creation of this book: Mary P. Clemons, Leonard Lang, Laura Littleford, Cindy Filipek Johnson, Daniel T. Max, Alice Martell, Paul J. Hintz, Bill Truesdale, Katie Maehr, and David Cline. Special thanks to the Cummington Community of the Arts, where most of this novel was written, and to the Ragdale Foundation and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, which have provided nurturing environments for my work to grow. Also to my friends and family—this is what you get for putting up with me. (Extra special thanks to Brian and Jim who water the plants when I’m gone.) Chapter One appeared in a slightly different form in Other Voices. Lines from “Sweet Dancer” are reprinted with the permission of Macmillan Publishing Company from The Poems of W. B. Yeats: A New Edition, edited by Richard J. Finneran. © 1940 by George Yeats, renewed 1968 by Bertha Georgie Yeats, Michael Butler Yeats, and Anne Yeats. New Rivers Press wishes to extend its heartfelt thanks, in memoriam, to Garth Tate and the Dayton Hudson Foundation. I I’M A VERY dangerous boy. I’ve been known to say almost anything. Sam and Rose—two people who are supposed to be my parents—have washed out my so-called fresh mouth with soap more than once, but not since I turned fifteen and turned into an overgrown moose. Just maybe it was my big mouth got us into this mess. I don’t think anyone knows or cares. -

Most Requested Songs of 2012

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2012 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 3 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 8 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 9 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 10 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 11 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 B-52's Love Shack 14 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 15 Pitbull Feat. Ne-Yo, Afrojack & Nayer Give Me Everything 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 18 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 19 Pink Raise Your Glass 20 Beatles Twist And Shout 21 Cruz, Taio Dynamite 22 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 23 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 24 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 25 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 26 Outkast Hey Ya! 27 Isley Brothers Shout 28 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 29 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 30 Sister Sledge We Are Family 31 Train Marry Me 32 Kool & The Gang Celebration 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Temptations My Girl 35 ABBA Dancing Queen 36 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 37 Flo Rida Good Feeling 38 Perry, Katy Firework 39 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 40 Jackson, Michael Thriller 41 James, Etta At Last 42 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 43 Lopez, Jennifer Feat. -

2020-2021 Mock Trial Competition

2020-2021 MOCK TRIAL COMPETITION Val Orr, Personal Representative of the Estate of Doane Orr, Deceased vs. Dis-Chord, Inc. 1 Thank you The State Bar of Nevada Mock Trial Committee sincerely thanks the Indiana Bar Foundation and Susan Roberts, case author, for permission to use this mock trial case. The case and materials have been edited for use in the 2020-2021 State Bar of Nevada Mock Trial Program. We extend our thanks to the Washoe County Bar Association for their continued support of the Mock Trial Program including logistics and funding. Many thanks to the Nevada Bar Foundation. The state bar’s Mock Trial Program is sustained through a Foundation grant funded by the Charles Deaner Living Trust. Chuck Deaner was a Nevada attorney and ardent supporter of law-related education. The state championship round is named in his honor. Mock Trial Committee Members Andrew Chiu, Chair, Staff Counsel for AIG Lisa Bruce, Bruce Law Group Sandra DiGiacomo, Clark County District Attorney’s Office Neal Falk, Minden Lawyers, LLC John Giordani, Clark County District Attorney’s Office Edmund “Joe” Gorman, Second Judicial District Court Kimberley Hyson, Kravitz, Schnitzer & Johnson Gale Kotlikova, Heshmati & Associates Erica Roth, Second Judicial District Court John Shook, Shook and Stone Emily Strand, Pitaro & Fumo Andrew Wong, Federal Public Defender’s Office 2 INTRODUCTION This year’s mock trial case involves the death of a concert attendee from a lightning strike during an outdoor concert. The Plaintiff is the spouse of the Decedent and the Personal Representative of the estate. Plaintiff is pursuing a wrongful death claim against the rock band, claiming the Defendant failed to cancel the concert due to the bad weather and failed to communicate weather conditions to concert goers. -

The Derailment of Feminism: a Qualitative Study of Girl Empowerment and the Popular Music Artist

THE DERAILMENT OF FEMINISM: A QUALITATIVE STUDY OF GIRL EMPOWERMENT AND THE POPULAR MUSIC ARTIST A Thesis by Jodie Christine Simon Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2010 Bachelor of Arts. Wichita State University, 2006 Submitted to the Department of Liberal Studies and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts July 2012 @ Copyright 2012 by Jodie Christine Simon All Rights Reserved THE DERAILMENT OF FEMINISM: A QUALITATIVE STUDY OF GIRL EMPOWERMENT AND THE POPULAR MUSIC ARTIST The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts with a major in Liberal Studies. __________________________________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Chair __________________________________________________________ Jeff Jarman, Committee Member __________________________________________________________ Chuck Koeber, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To my husband, my mother, and my children iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my adviser, Dr. Jodie Hertzog, for her patient and insightful advice and support. A mentor in every sense of the word, Jodie Hertzog embodies the very nature of adviser; her council was very much appreciated through the course of my study. v ABSTRACT “Girl Power!” is a message that parents raising young women in today’s media- saturated society should be able to turn to with a modicum of relief from the relentlessly harmful messages normally found within popular music. But what happens when we turn a critical eye toward the messages cloaked within this supposedly feminist missive? A close examination of popular music associated with girl empowerment reveals that many of the messages found within these lyrics are frighteningly just as damaging as the misogynistic, violent, and explicitly sexual ones found in the usual fare of top 100 Hits.