Read: the Legacy of Joseph W. Penfold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness Act and Howard Zahniser

WILDERNESS ACT AND HOWARD ZAHNISER In: The Fully Managed, Multiple-Use Forest Era, 1960-1970 Passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964 involved decades of work on the part of many people both inside the Forest Service and from a variety of interest groups. As early as the 1910’s and 1920’s, there were several important proponents of wilderness designation in the national forests. Three men are considered pivotal in these early years and all were Forest Service employees: Aldo Leopold, Arthur H. Carhart, and Robert Marshall. Their efforts were successful at the local level in creating administratively designated wilderness protection for several areas across the country. At the national policy level, there was a series of policy decisions (L-20 and U Regulations) in the 1920’s and 1930’s that made wilderness and primitive area designation relatively easy, but what was lacking was a common standard of management across the country for these areas. Also, since these wilderness and primitive areas were administratively designated, the next Chief or Regional Forester could “undesignate” any of the areas with the stroke of a pen. Howard C. Zahniser, executive secretary of the Wilderness Society (founded by Bob Marshall), became the leader in a movement for congressionally designated wilderness areas. In 1949, Zahniser detailed his proposal for Federal wilderness legislation in which Congress would establish a national wilderness system, identify appropriate areas, prohibit incompatible uses, list potential new areas, and authorize a commission to recommend changes to the program. Nothing much happened to the proposal, but it did raise the awareness for the need to protect wilderness and primitive areas from all forms of development. -

Wilderness, Recreation, and Motors in the Boundary Waters, 1945-1964

Sound Po lit ics SouWildernessn, RecdreatioPn, ano d Mlotoris itn theics Boundary Waters, 1945–1964 Mark Harvey During the midtwentieth century, wilderness Benton MacKaye, executive director Olaus Murie and his preservationists looked with growing concern at the wife Margaret, executive secretary and Living Wilderness boundary waters of northeast Minnesota and northwest editor Howard Zahniser, University of Wisconsin ecolo - Ontario. Led by the Friends of the Wilderness in Minne - gist Aldo Leopold, and Forest Service hydrologist Ber- sota and the Wilderness Society in the nation’s capital, nard Frank. 1 preservationists identified the boundary waters as a pre - MacKaye’s invitation to the council had identified the mier wilderness and sought to enhance protection of its boundary waters in richly symbolic terms: magnificent wild lands and waterways. Minnesota’s con - servation leaders, Ernest C. Oberholtzer and Sigurd F. Here is the place of places to emulate, in reverse, the Olson among them, played key roles in this effort along pioneering spirit of Joliet and Marquette. They came to with Senator Hubert H. Humphrey. Their work laid the quell the wilderness for the sake of civilization. We come foundation for the federal Wilderness Act of 1964, but it to restore the wilderness for the sake of civilization. also revived the protracted struggles about motorized re c - Here is the central strategic point from which to reation in the boundary waters, revealing a deep and per - relaunch our gentle campaign to put back the wilderness sistent fault line among Minnesota’s outdoor enthusiasts. on the map of North America. 2 The boundary waters had been at the center of numer - ous disputes since the 1920s but did not emerge into the Putting wilderness back on the continent’s map national spotlight of wilderness protection until World promised to be a daunting task, particularly when the War II ended. -

The Wilderness Act of 1964

The Wilderness Act of 1964 Expanding Settlement Growing Mechanization “Wilderness protection is paper thin, and the paper should be the best we can get — that Versus upon which Congress prints its Acts.” David Brower, 1956 “Let’s be done with a wilderness preservation program made up of a sequence of threats and defense campaigns! Let’s make a concerted effort for a positive program … where we can be at peace and not forever feel that the wilderness is a battleground.” Howard Zahniser 1951 “If future generations are to remember us with gratitude rather than contempt, we must leave them more than the miracles of technology. We must leave them with a glimpse of the world as it was in the beginning, not just after we got through with it”. Lyndon B. Johnson Wilderness Act of 1964 Statement of Policy “ …to assure that an increasing population, accompanied by expanding settlement and growing mechanization, does not occupy and modify all areas within the United States and its possessions, leaving no lands designated for preservation and protection in their natural condition…” Sec 2(a) Wilderness Act of 1964 Statement of Policy “…it is hereby declared to be the policy of the Congress to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness.” Sec 2(a) The Wilderness Act….. 1. Created a NWPS and established a process for adding new areas NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM 1964 9.1 Mil Acres 54 Wilderness Areas 2014 109.8 Mil Acres 762 Wilderness Areas The Wilderness Act….. 2. -

Preservation of Man ” 1851 • Philosopher • Emerson Transcendentalism

What are NR’s? • Tangible substance • Function or use What is an environment? • A collection of NR’s in a defined area What is a Ecosystem • All of the ecological processes in a n environment What is wilderness? • Theoretically an undisturbed environment • Big “W” • Little “w” U. S. History and the Environment • Growth of the U.S. • Traditional view of NRs • 1890 closing of the frontier • CidliConservation and population Modern View of the Environment • Technology • Wilderness • Product of civilization • 3rd world European View of Wilderness • European landscape of the 1600s • Perception of wilderness • Basis of bias - RliiReligion - Superstition and folklore Settlers View of the NA Wilderness • Paradise Myth • Reality • Not prepared to live “with” the env. Settlers’ Bias on the Frontier • Safety • Effect of wilderness • Doing God’s work – Manifest Destiny • Wilderness = waste Romanticism • Late 1700s – mid 1800s • Urban, educated , wealthy • Writers and artists • CiCoincid es wi ihhth the growth of sci ences • Enthusiasm for wild places Romanticism • Sublimity • Awe •Deism • GhkhGreat watchmaker theory • Primitivism • The noble savage Start of the American Environmental Movement • Europe = history, cities, culture • USU.S. = Wilderness, NRs • American wilderness = American character • MifDManifest Dest iny Hudson River School • American wild landscape as inspiration • Thomas Cole • First American art form • View o f Amer ican art ist, wri ter, etc Henry David Thoreau • 1817 – 1862 •“In wilderness is the preservation of man ” 1851 • Philosopher -

David Brower: the Making of the Environmental Movement by Tom Turner

Review: David Brower: The Making of the Environmental Movement By Tom Turner Reviewed by Byron Anderson DeKalb, Illinois, USA Turner, Tom. David Brower: The Making of the Environmental Movement. University of California Press, 2015; x, 308 pp. ISBN: 978-0-520-27836-3 US $29.95 cloth; 978-1- 520-96245-3 US$29.95 ebook . Printed on 30 percent post-consumer waste paper. In the Foreword, Bill McKibben equates Bower to John Muir and regards Brower as the most important conservationist in twentieth century America. David Bower had an “indomitable spirit” that “drew you in” (p. x). Yet, for those who personally knew him, Brower was a complicated person who, depending on the circumstances, could be labeled as charismatic, imaginative, aggressive, or reckless, among other descriptors. Among his more notable flaws, he had difficultly falling in line with authority, such as, bylaws and board directives. Brower was a long-time member of the Sierra Club and was its one and only executive director. Brower moved the Sierra Club from an outings club to a conservation club, a move that greatly increased the membership. He led campaigns to create parks, block dams, and in working with Howard Zahniser, win passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964. Brower also had failures, for example, supporting Glen Canyon Dam in trade for blocking two dams in the Dinosaur National Monument. In later years he realized that Glen Canyon would have been well worth saving as well. Brower pioneered in the effective use of mass media, including films, Exhibit Format books, and full newspaper ads. -

November 2004 Court Rules Park Service Violates Wilderness Act End of Motorized Vehicle Tours in Georgia’S Cumberland Island Wilderness

NESS W R A E T WILDERNESS D C L I H W • WATCHER • K E D E IL P W IN G SS WILDERNE A Voice for Wilderness Since 1989 The Quarterly Newsletter of Wilderness Watch Volume 15 Number 3 November 2004 Court Rules Park Service Violates Wilderness Act End of motorized vehicle tours in Georgia’s Cumberland Island Wilderness — By George Nickas he U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit recently slammed the door on the National Park TService’s motorized sight-seeing tours through the Cumberland Island Wilderness. In one of the most detailed and powerful court opinions for Wilderness preservation, the three judge panel ruled that the motorized tours violate both the Wilderness Act and the National Environmental Policy Act. The ruling puts a stop to the sight-seeing tours the park service initiated in 1999 as a part of an “agreement” be- tween anti-wilderness factions on the island, Clinton administration officials, a local Congressman and some conservation groups. Wilderness Watch opposed the agreement arguing that motorized tours in Wilderness were illegal and damaging to the area’s wilderness character. The Celebrate 40 Cumberland hiker. WW file photo. years Wilderness court agreed, writing that “The language of the …Wilder- ness Act demonstrate[s] that Congress has unambiguously prohibited the Park Service from offering motorized trans- portation to park visitors through the wilderness area.” No increase in motorboat permits for Boundary Waters Wilderness, by Kevin Proescholdt. Page 3 Cumberland Island contains historic structures dating from the late 1800s to mid-1900s. Most of the popular tour Celebrating Wilderness in 2004, by Roderick sites lie outside the Wilderness boundary on the south end Frazier Nash. -

Untrammeled WILDERNESS

Untrammeled WILDERNESS KEVIN PROESCHOLDT ?hkfZgrFbgg^lhmZglZg]hma^klZ\khllma^\hngmkr%Zoblbmmhhg^h_hnkgZmbhgÍl]^lb`& gZm^]pbe]^kg^llZk^ZlblZab`aeb`amh_ma^r^Zk'Ma^;hng]ZkrPZm^kl<Zgh^:k^ZPbe]^kg^ll !;P<:P"bgghkma^Zlm^kgFbgg^lhmZaZl[^^gma^gZmbhgÍlfhlmihineZkZg]fhlmoblbm^] ik^l^ko^_hk]^\Z]^l'Fbgg^lhmZZelhaZlmphe^ll^k&dghpg_^]^kZepbe]^kg^llZk^Zl3ma^:`Zl& lbsPbe]^kg^llg^ZkMab^_Kbo^k?Zeel%Zg]ma^MZfZkZ\Pbe]^kg^ll[r=^mkhbmEZd^l'Pabe^ ^__hkmlmh]^lb`gZm^Zk^Zlebd^ma^;P<:PZlpbe]^kg^llaZo^k^\^bo^]fn\ain[eb\Zmm^gmbhg% ma^lmhkrh_hg`hbg`lm^pZk]labiZg]ikhm^\mbhgblh_m^gg^`e^\m^]'* Ma^phk]ngmkZff^e^]blma^d^r]^l\kbimhkbgma^Pbe& fhk^maZg0))Zk^ZlZg]*)0fbeebhgZ\k^l':eeh_ma^l^ ]^kg^ll:\mh_*2/-maZm]^lb`gZm^]Zg]ikhm^\mlpbe]^k& Zk^ZlZk^`ho^kg^][rma^*2/-eZpZg]bmlfZg]Zm^mh g^llZk^ZlZ\khllma^\hngmkr%bg\en]bg`paZmblghpdghpg ikhm^\mma^\aZkZ\m^kh_ngmkZff^e^]pbe]^kg^ll' Zlma^;P<:P'Bgi^kaZilma^fhlmih^mb\iZllZ`^bgZgr _^]^kZelmZmnm^%mableZp^ehjn^gmer]^Ög^]Zpbe]^kg^ll ZlÊZgZk^Zpa^k^ma^^ZkmaZg]bml\hffngbmrh_eb_^Zk^ AhpZk]SZagbl^k%pahl^ko^]Zl^q^\nmbo^l^\k^mZkr ngmkZff^e^][rfZg%pa^k^fZgabfl^e_blZoblbmhkpah h_ma^Pbe]^kg^llLh\b^mr_khf*2-.mh*2/-%eZk`^er ]h^lghmk^fZbg'Ë=^libm^k^\^gmablmhkb\Zek^l^Zk\a%ma^ pkhm^ma^Pbe]^kg^ll:\mZg]inkihl^er\ahl^ma^phk] _neef^Zgbg`Zg]lhf^h_ma^bglibkZmbhg_hk\ahhlbg`mabl ngmkZff^e^]'Ma^l\aheZkerÊSZagb^%ËZlabl_kb^g]l mhn\almhg^phk]k^fZbgebmme^dghpghkng]^klmhh]'+ \Zee^]abf%eho^][hhdlZg]ebm^kZmnk^%mahn`am]^^ier Ma^*2/-Z\m%bgZ]]bmbhgmh]^Ögbg`pbe]^kg^ll Z[hnmpbe]^kg^lloZen^l%Zg]pZlZd^^gphk]lfbmabg Zk^ZlZg]fZg]Zmbg`ma^bkikhm^\mbhg%Zelh^lmZ[ebla^] ablhpgkb`am'A^^]bm^]ma^hk`ZgbsZmbhgÍlfZ`Zsbg^%Ma^ -

Can You Introduce Yourself and Tell Us How You Are Working with Wilderness?

INTERVIEW WITH EDWARD ZAHNISER BY LAURA BUCHHEIT and MARK MADISON AUGUST 11, 2004, NCTC, SHEPHERDSTOWN, WV MS. BUCHHEIT: Can you introduce yourself and tell us how you are working with wilderness? MR. ZAHNISER: I got into working with wilderness by accident of birth. My father Howard Zahniser worked for the Wilderness Society in Washington, D.C. from a few months before my birth in 1945 until his death in 1964. I grew up among the people of the early Wilderness Society and the early wilderness movement. And just as any young kid growing up would, I merely thought of these people as my father’s associates and people who showed up in Washington occasionally. We lived in the Washington, D.C. suburbs, in Maryland. But we spent many summers in the wilderness of the Adirondacks, and later in other wild areas throughout the country. At age 15 I was able to go to the Sheenjek country in Alaska—in what is now part of the Artic National Wildlife Refuge—with Olaus and Mardy Murie. From there we went down to what is now Denali National Park and Preserve with Adolph and Louise Murie. It was then Mount McKinley National Park, Adolph was in Denali working on his book on Alaska bears then, so we had a couple of weeks there in Mount McKinley National Park. That was probably the most influential summer of my life. From that trip, when I got back to the Washington area, I just went up to the Adirondacks with my mother and one of my siblings for the rest of the summer. -

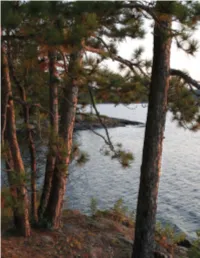

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug 2002) (Expires: 1-31-2009) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places -2007 Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to CompleWiri^^tionA[-Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Listening Point other names/site number 2. Location street & number 3128 Listening Point Road D not for publication N/A city or town Morse Township Ely vicinity state Minnesota code MN county St. Louis code 137 zip code 55731 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property Exl meets D does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant ^nationally Qstatewide D locally. -

Wilderness Imperatives and Untrammeled Nature Sandra Zellmer University of Nebraska College of Law, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln College of Law, Faculty Publications Law, College of 2014 Wilderness Imperatives and Untrammeled Nature Sandra Zellmer University of Nebraska College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/lawfacpub Part of the Environmental Law Commons Zellmer, Sandra, "Wilderness Imperatives and Untrammeled Nature" (2014). College of Law, Faculty Publications. 193. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/lawfacpub/193 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Law, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. C:/ITOOLS/WMS/CUP-NEW/4664335/WORKINGFOLDER/HIRO/9781107033474C09.3D 179 [179–199] 7.1.2014 9:32AM 9 Wilderness Imperatives and Untrammeled Nature 1 Sandra Zellmer introduction Wilderness is often considered the epitome of naturalness – what nature ought to be. Indeed, in many ways, society, through its environmental laws, has prioritized the protection of wilderness over other areas of nature and other aspects of naturalness. We give our wilderness areas iconic names, like Delirium, Desolation, Devil’s Backbone, River of No Return, and Superstition, and we idealize them and treat them as something utterly unique and apart from our technology-ridden daily lives. The nation’s preeminent wilderness statute, the Wilderness Act of 1964, is credited with significant preservation achievements. Over the years, the Act has remained remarkably robust, with few legislative revisions. The Act is so well loved that, as Professor Rodgers notes, it is “virtually 2 repeal-proof.” During almost every congressional session since 1964,new wilderness areas have been added to the system or existing areas have been expanded. -

Mountain Biking in Wilderness Some History

Mountain Biking in Wilderness Some History by Douglas W. Scott u from WILD EARTH Wild Time Wilderness System Under Siege The Language of Loons Mountain Bikes in Wilderness? Vol. 13, No. 1 Spring 2003 pp. 23–25 Published by the Wildlands Project 802-434-4077 u P.O. Box 455, Richmond, VT 05477 [email protected] u www.wildlandsproject.org Wild Earth ©2003 by the Wildlands Project “Mountain Biking in Wilderness: Some History” ©2003 Douglas W. Scott illustrations ©Suzanne DeJohn MacKaye, Marshall, Leopold, and the others who found- Mountain Biking in Wilderness ed the Wilderness Society in 1935 saw wilderness as “a seri- ous human need rather than a luxury and plaything,” con- Some History cluding that “…this need is being sacrificed to the mechanical invasion in its various killing forms.” Expressing their concern by Douglas W. Scott about human intrusions that bring “into the wilderness a fea- ture of the mechanical Twentieth Century world,” the society’s founders identified wilderness areas as “regions which possess In December 1933, the director of the National Park no means of mechanical conveyance.”7 Service floated the idea that construction of the Skyline Drive parkway along the wild ridgetops of Shenandoah National The words of the Wilderness Act Park would be a terrific opportunity for that section of the As historian Paul Sutter notes, “for Leopold the essential qual- Appalachian Trail to “be made wide and smooth enough that ity of wilderness was how one traveled and lived within its it could serve as a bicycle path.”1 confines,” a view shared by the other founders of the Benton MacKaye, father of the Appalachian Trail, was Wilderness Society.8 As he drafted the Wilderness Act in apoplectic. -

December 2006

NESS W R A E T D C L I H W WILDERNESS • • K E D E IL WATCHER P W IN S G S WILDERNE The Quarterly Newsletter of Wilderness Watch Volume 17 • Number 4 • December 2006 j2006j Reflecting Back, Looking Ahead 2 006 was a wild ride for wilderness, as a Whew! number of local and national challenges worked their way to showdowns. With major threats pending simultaneously on several fronts, the year found Wilderness Watch working intensively with other conservation groups and citizen advocates around the country. It is with relief and pride that we can report that 2006 is ending on a positive and very hopeful note for wilderness, with many serious harms dodged or defeated, with strides made in wilderness protec- tions, and with promising new opportunities on the horizon. A very heartening trend picked up steam in 2006 as real wilderness gained increasing support from members of Con- gress, the federal courts, and some policy-makers. Wilderness Watch’s efforts played a significant role in generating greater concern among key leaders about the condition of our National Wilderness Preservation System. For example, during last year’s winter holidays Wilderness Central Idaho wildlands. Watch worked feverishly to convince the Forest Service to deny helicopter landings in the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness in Idaho for darting and collaring wolves. Through by the Regional Forester into a public debate that ultimately led our leadership, a coalition of wilderness advocates came together to canceling the proposal. quickly and turned what was anticipated to be routine approval Later in the year we raised the alarm over proposed new poli- cies that would permit aerial gunning and poisoning of preda- tors in national forest wilderness.