Private Exercise of Governmental Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effective Thermal Fire-Extinguishing Agents

NIST Technical Note 1440 Characteristics and Identification of Super- Effective Thermal Fire-Extinguishing Agents: Final Report, NGP Project 4C/1/890 William M. Pitts Jiann C. Yang Rodney A. Bryant Linda G. Blevins Marcia L. Huber NIST Technical Note 1440 Characteristics and Identification of Super- Effective Thermal Fire-Extinguishing Agents: Final Report, NGP Project 4C/1/890 William M. Pitts Jiann C. Yang Rodney A. Bryant Linda G. Blevins Building and Fire Research Laboratory Marcia L. Huber Chemical Science and Technology Laboratory June 2001 Issued July 2006 U.S. Department of Commerce Donald L. Evans, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Dr. Karen H. Brown, Acting Director Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose. National Institute of Standards and Technology Technical Note 1440 Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Tech. Note 1440, 138 pages (July 2006) CODEN: NSPUE2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................................................................ iii LISTS OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................ -

Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses | a National Survey | Shook, Hardy & Bacon

2020 — Force Majeure SHOOK SHB.COM and Common Law Defenses A National Survey APRIL 2020 — Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses A National Survey Contractual force majeure provisions allocate risk of nonperformance due to events beyond the parties’ control. The occurrence of a force majeure event is akin to an affirmative defense to one’s obligations. This survey identifies issues to consider in light of controlling state law. Then we summarize the relevant law of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. 2020 — Shook Force Majeure Amy Cho Thomas J. Partner Dammrich, II 312.704.7744 Partner Task Force [email protected] 312.704.7721 [email protected] Bill Martucci Lynn Murray Dave Schoenfeld Tom Sullivan Norma Bennett Partner Partner Partner Partner Of Counsel 202.639.5640 312.704.7766 312.704.7723 215.575.3130 713.546.5649 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SHOOK SHB.COM Melissa Sonali Jeanne Janchar Kali Backer Erin Bolden Nott Davis Gunawardhana Of Counsel Associate Associate Of Counsel Of Counsel 816.559.2170 303.285.5303 312.704.7716 617.531.1673 202.639.5643 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] John Constance Bria Davis Erika Dirk Emily Pedersen Lischen Reeves Associate Associate Associate Associate Associate 816.559.2017 816.559.0397 312.704.7768 816.559.2662 816.559.2056 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Katelyn Romeo Jon Studer Ever Tápia Matt Williams Associate Associate Vergara Associate 215.575.3114 312.704.7736 Associate 415.544.1932 [email protected] [email protected] 816.559.2946 [email protected] [email protected] ATLANTA | BOSTON | CHICAGO | DENVER | HOUSTON | KANSAS CITY | LONDON | LOS ANGELES MIAMI | ORANGE COUNTY | PHILADELPHIA | SAN FRANCISCO | SEATTLE | TAMPA | WASHINGTON, D.C. -

'Capacitas': Contract Law and the Institutional

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics ‘CAPACITAS’: CONTRACT LAW AND THE INSTITUTIONAL PRECONDITIONS OF A MARKET ECONOMY Centre for Business Research, University Of Cambridge Working Paper No. 325 by Simon Deakin University of Cambridge Centre for Business Research Judge Business School Building Trumpington Street Cambridge CB2 1AG Email: [email protected] June 2006 This working paper forms part of the CBR Research Programme on Corporate Governance. Abstract Capacity may be defined as a status conferred by law for the purpose of empowering persons to participate in the operations of a market economy. This paper argues that because of the confining influence of the classical private law of the nineteenth century, we currently lack a convincing theory of the role of law in enhancing and protecting the substantive contractual capacity of market agents, a notion which resembles the economic concept of ‘capability’ as developed by Amartya Sen. Re-examining the legal notion of capacity from the perspective of Sen’s ‘capability approach’ is part of a process of understanding the preconditions for a sustainable market order under modern conditions. JEL Classification : K12, K31 Keywords : contract law, capacity, capability approach Acknowledgements This paper is based on the work of the ‘Capacitas’ project which was funded by the European Union’s Fifth Framework Programme, as part of a wider research network examining the politics of capabilities in Europe (‘Eurocap’). I am grateful to fellow project-members who took part in meetings in Nantes and Cambridge in 2003 and 2005 respectively and whose work I draw on here, in particular Wiebke Brose, Sandrine Godelain, Jean Hauser, Martin Hesselink, Alain Supiot and Aurora Vimercati. -

Department of Veterans Affairs VA Directive 0000 Washington, DC 20420 Transmittal Sheet November 14, 2018

Department of Veterans Affairs VA Directive 0000 Washington, DC 20420 Transmittal Sheet November 14, 2018 DELEGATIONS OF AUTHORITY 1. REASON FOR ISSUE: Directive 0000 is being reissued to update policy regarding VA Delegations Of Authority (DOA). 2. SUMMARY OF CONTENTS/MAJOR CHANGES: This revised directive announces changes in the responsible office from the Office of Information and Technology (OIT) to the Office of Enterprise Integration (OEI), establishes an Enterprise Delegation Control Officer within OEI, and clarifies roles and responsibilities of officials managing the Delegation of Authority program for the enterprise. 3. RESPONSIBLE OFFICE(S): The Office of Policy and Interagency Collaboration (008D3) within the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Enterprise integration (008). 4. RELATED HANDBOOK: None. 5. RESCISSION: VA Directive 0000, Delegations of Authority, dated September 9, 2009. CERTIFIED BY: BY THE DIRECTION OF THE SECRETARY OF VETERANS AFFAIRS: /s/ /s/ Melissa S. Glynn, Ph.D. Melissa S. Glynn, Ph.D. Assistant Secretary Assistant Secretary for Enterprise Integration for Enterprise Integration DISTRIBUTION: Electronic Only VA Directive 0000 November 14, 2018 This page is intentionally left blank. 2 November 14, 2018 VA Directive 0000 DELEGATIONS OF AUTHORITY 1. PURPOSE AND SCOPE. This directive sets forth policies for issuing delegations of authority from the Secretary of Veterans Affairs, Deputy Secretary of Veterans Affairs, Chief of Staff, Assistant Secretaries, Under Secretaries, and Other Key Officials. Section 512(a) of title 38 of the United States Code (U.S.C.), allows the Secretary to delegate, except as otherwise provided by law, the authority to act or render decisions with respect to all laws administered by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). -

Lesser Known Breach of Contract Defenses

LESSER KNOWN BREACH OF CONTRACT DEFENSES Jack A. Walters, III Cooper & Scully, P.C. Founders Square 900 Jackson Street, Suite 100 Dallas, Texas 75202 (214) 712-9500 (214) 712-9540 fax www.cooperscully.com [email protected] 3rd Annual Construction Symposium January 25, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND ON CONSTRUCTION CONTRACTS..................................................1 A. Contract Documents...............................................................................................1 B. Checklist of Issues Covered in a Contract..............................................................1 C. Definitions..............................................................................................................2 III. CONTRACT DEFENSES...................................................................................................3 A. Limitations (Statute of Limitations & Statute of Repose)......................................3 B. Standing/Privity......................................................................................................5 C. Failure of consideration / Lack of consideration....................................................6 D. Mistake 7 E. Ratification.............................................................................................................8 F. Waiver 9 G. Plaintiff's Prior Material Breach.............................................................................9 -

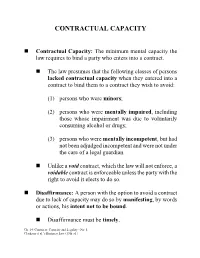

Contractual Capacity

CONTRACTUAL CAPACITY Contractual Capacity: The minimum mental capacity the law requires to bind a party who enters into a contract. The law presumes that the following classes of persons lacked contractual capacity when they entered into a contract to bind them to a contract they wish to avoid: (1) persons who were minors; (2) persons who were mentally impaired, including those whose impairment was due to voluntarily consuming alcohol or drugs; (3) persons who were mentally incompetent, but had not been adjudged incompetent and were not under the care of a legal guardian. Unlike a void contract, which the law will not enforce, a voidable contract is enforceable unless the party with the right to avoid it elects to do so. Disaffirmance: A person with the option to avoid a contract due to lack of capacity may do so by manifesting, by words or actions, his intent not to be bound. Disaffirmance must be timely. Ch. 14: Contracts: Capacity and Legality - No. 1 Clarkson et al.’s Business Law (13th ed.) MINORITY Subject to certain exceptions, an unmarried legal minor (in most states, someone less than 18 years old) may avoid a contract that would bind him if he were an adult. Contracts entered into by young children and contracts for something the law permits only for adults (e.g., a contract to purchase cigarettes or alcohol) are generally void, rather than voidable. Right to Disaffirm: Generally speaking, a minor may disaffirm a contract at any time during minority or for a reasonable time after he comes of age. When a minor disaffirms a contract, he can recover all property that he has transferred as consideration – even if it was subsequently transferred to a third party. -

Unit 6 – Contracts

Unit 6 – Contracts I. Definition A contract is a voluntary agreement between two or more parties that a court will enforce. The rights and obligations created by a contract apply only to the parties to the contract (i.e., those who agreed to them) and not to anyone else. II. Elements In order for a contract to be valid, certain elements must exist: (A) Competent parties. In order for a contract to be enforceable, the parties must have legal capacity. Even though most people can enter into binding agreements, there are some who must be protected from deception. The parties must be over the age of majority (18 under most state laws) and have sufficient mental capacity to understand the significance of the contract. Regarding the age requirement, if a minor enters a contract, that agreement can be voided by the minor but is binding on the other party, with some exceptions. (Contracts that a minor makes for necessaries such as food, clothing, shelter or transportation are generally enforceable.) This is called a voidable contract, which means that it will be valid (if all other elements are present) unless the minor wants to terminate it. The consequences of a minor avoiding a contract may be harsh to the other party. The minor need only return the subject matter of the contract to avoid the contract. if the subject matter of the contract is damaged the loss belongs to the nonavoiding party, not the minor. Regarding the mental capacity requirement, if the mental capacity of a party is so diminished that he cannot understand the nature and the consequences of the transaction, then that contract is also voidable (he can void it but the other party can not). -

GEORGIA STATUTORY FINANCIAL POWER of ATTORNEY Instructions and Form

GEORGIA STATUTORY FINANCIAL POWER OF ATTORNEY Instructions and Form INTRODUCTION The General Assembly enacted the Uniform Power of Attorney Act during the 2017 legislative session. Within this Act is a revised form for a power of attorney. While this new Act does not require that the new form be used, it does replace the former Statutory Financial Power of Attorney form previously in the law. The narrative that precedes the form, provides some guidance to understanding and instruction for executing the new form. However, this guidance and instruction is not meant to replace any needed legal advice on the purpose, intent and use of this or any other legal document. Any power of attorney validly executed before July 1, 2017, remains effective unless and until the principal chooses to revoke it, it terminates automatically according to the language of the power of attorney document or until a court of competent jurisdiction orders it terminated. A FINANCIAL POWER OF ATTORNEY This document contains information about the "Statutory Financial Power of Attorney." It allows you to name one or more persons to help you handle your financial affairs. Depending on your individual circumstances, you can give this person complete or limited power to act on your behalf. This document does not give someone the power to make medical decisions or personal health decisions for you. EFFECT OF GIVING POWERS AWAY Even with this document, you may still legally make decisions about your own financial affairs as long as you choose to or are able to. Talk to your Agent often about what you want and what he or she is doing for you using the document. -

Contracts Outline

Contracts Outline NYU Fall 2004, Professor Barry Friedman Chapter 1 What Promise Ought We Enforce.............................................................. 8 1. Why we enforce promise......................................................................................... 8 1.1. Moral claim (Foundational) ........................................................................ 8 1.2. Efficiency / Mutual exchange: we can not exchange things simultaneously.............................................................................................. 8 1.3. Reliance: somebody relies on the promise and changes his plan............. 8 1.4. Will theory: somebody makes the promise means he wants the promise to be enforced. .............................................................................................. 8 1.5. Benefits unjustly retained............................................................................ 8 2. Promise with good consideration........................................................................... 8 2.1. Bargain for exchange is the test of good consideration ............................ 8 2.2. Past consideration is no good consideration.............................................. 9 2.3. Moral promise could be enforced under material benefit rule................ 9 2.4. Illusory promise is no good consideration ................................................. 9 2.5. Conditional promise could be good consideration.................................. 10 2.6. Good consideration could be implied...................................................... -

Chapter 3. STATUTE of FRAUDS CHAPTER 3

MRS Title 33, Chapter 3. STATUTE OF FRAUDS CHAPTER 3 STATUTE OF FRAUDS §51. Writing required; consideration need not be expressed No action shall be maintained in any of the following cases: 1. Executor or administrator. To charge an executor or administrator upon any special promise to answer damages out of his own estate; 2. Debt of another. To charge any person upon any special promise to answer for the debt, default or misdoings of another; 3. Agreement of marriage. To charge any person upon an agreement made in consideration of marriage; 4. Contract for sale of land. Upon any contract for the sale of lands, tenements or hereditaments, or of any interest in or concerning them; 5. Agreement not to be performed within one year. Upon any agreement that is not to be performed within one year from the making thereof; 6. Contract to pay debt discharged in bankruptcy. Upon any contract to pay a debt after a discharge therefrom under the bankrupt laws of the United States, or assignment or insolvent laws of this State; 7. Agreement to give property by will. Upon any agreement to give, bequeath or devise by will to another, any property, real, personal or mixed; 8. Agreement to refrain from carrying on any business. Upon any agreement to refrain from carrying on or engaging in any trade, business, occupation or profession for any term of years or within any defined territory or both; the provisions of this subsection shall not apply to any such agreement made prior to August 13, 1947; unless the promise, contract or agreement on which such action is brought, or some memorandum or note thereof, is in writing and signed by the party to be charged therewith, or by some person thereunto lawfully authorized; but the consideration thereof need not be expressed therein, and may be proved otherwise. -

Public View on Capacity to Contract in Case of Occurrence of Fraud

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-9 Issue-2, December 2019 Public View on Capacity to Contract in Case of Occurrence of Fraud R.Thilagavathy, M.Dhinesh Abstract: This Study is all about Capacity to Contract in Case This means that the individual that lacks legal competence Of Occurrence Of Fraud. The main aim of the study is to create to enter a agreement is capable of void the agreement at any awareness about Mer silence would amount to fraud. A man or time (Christopher 2012). However, the character also has woman is believed to have the potential to go into right into a contract. An intoxicated person, minor, or mentally incapable the option to allow the settlement to move ahead as character has options to be had to them after getting into an deliberate.Most people assume that they can input into a agreement which influences the validity of the agreement into settlement. People who're minors, intoxicated, or mentally which they've entered. The first alternative they have got is to unwell have several alternatives to pick from after they enter disaffirm a agreement. For the purpose of the study, descriptive into an agreement (Dusty and Ray 1887). They can research is used. Descriptive research helps to portray accurately determine to disaffirm the settlement, which is their desire the characteristics of particular individual, situation or group. Convenience sampling method is used in this study to collect the to not be bound by way of the agreement anymore (Dusty samples. When population elements are selected for inclusion in and Ray 1887. -

Contract Basics for Litigators: Illinois by Diane Cafferata and Allison Huebert, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation

STATE Q&A Contract Basics for Litigators: Illinois by Diane Cafferata and Allison Huebert, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation Status: Law stated as of 01 Jun 2020 | Jurisdiction: Illinois, United States This document is published by Practical Law and can be found at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/w-022-7463 Request a free trial and demonstration at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/about/freetrial A Q&A guide to state law on contract principles and breach of contract issues under Illinois common law. This guide addresses contract formation, types of contracts, general contract construction rules, how to alter and terminate contracts, and how courts interpret and enforce dispute resolution clauses. This guide also addresses the basics of a breach of contract action, including the elements of the claim, the statute of limitations, common defenses, and the types of remedies available to the non-breaching party. Contract Formation to enter into a bargain, made in a manner that justifies another party’s understanding that its assent to that 1. What are the elements of a valid contract bargain is invited and will conclude it” (First 38, LLC v. NM Project Co., 2015 IL App (1st) 142680-U, ¶ 51 (unpublished in your jurisdiction? order under Ill. S. Ct. R. 23) (citing Black’s Law Dictionary 1113 (8th ed.2004) and Restatement (Second) of In Illinois, the elements necessary for a valid contract are: Contracts § 24 (1981))). • An offer. • An acceptance. Acceptance • Consideration. Under Illinois law, an acceptance occurs if the party assented to the essential terms contained in the • Ascertainable Material terms.