The Story of Subspace Zhichun Pu STS 145 Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELECTRONIC ARTS INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Speciñed in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ≤ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15 (d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Ñscal year ended March 31, 2003 OR n TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15 (d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File No. 0-17948 ELECTRONIC ARTS INC. (Exact name of Registrant as speciÑed in its charter) Delaware 94-2838567 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) IdentiÑcation No.) 209 Redwood Shores Parkway Redwood City, California 94065 (Address of principal executive oÇces) (Zip Code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: (650) 628-1500 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: None Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Class A Common Stock, $.01 par value (Title of class) Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has Ñled all reports required to be Ñled by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to Ñle such reports), and (2) has been subject to such Ñling requirements for the past 90 days. YES ≤ NO n Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent Ñlers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of registrant's knowledge, in deÑnitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. -

Disruptive Innovation and Internationalization Strategies: the Case of the Videogame Industry Par Shoma Patnaik

HEC MONTRÉAL Disruptive Innovation and Internationalization Strategies: The Case of the Videogame Industry par Shoma Patnaik Sciences de la gestion (Option International Business) Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de maîtrise ès sciences en gestion (M. Sc.) Décembre 2017 © Shoma Patnaik, 2017 Résumé Ce mémoire a pour objectif une analyse des deux tendances très pertinentes dans le milieu du commerce d'aujourd'hui – l'innovation de rupture et l'internationalisation. L'innovation de rupture (en anglais, « disruptive innovation ») est particulièrement devenue un mot à la mode. Cependant, cela n'est pas assez étudié dans la recherche académique, surtout dans le contexte des affaires internationales. De plus, la théorie de l'innovation de rupture est fréquemment incomprise et mal-appliquée. Ce mémoire vise donc à combler ces lacunes, non seulement en examinant en détail la théorie de l'innovation de rupture, ses antécédents théoriques et ses liens avec l'internationalisation, mais en outre, en situant l'étude dans l'industrie des jeux vidéo, il découvre de nouvelles tendances industrielles et pratiques en examinant le mouvement ascendant des jeux mobiles et jeux en lignes. Le mémoire commence par un dessein des liens entre l'innovation de rupture et l'internationalisation, sur le fondement que la recherche de nouveaux débouchés est un élément critique dans la théorie de l'innovation de rupture. En formulant des propositions tirées de la littérature académique, je postule que les entreprises « disruptives » auront une vitesse d'internationalisation plus élevée que celle des entreprises traditionnelles. De plus, elles auront plus de facilité à franchir l'obstacle de la distance entre des marchés et pénétreront dans des domaines inconnus et inexploités. -

What the Games Industry Can Teach Hollywood About DRM

Consumers, Fans, and Control: What the Games Industry can teach Hollywood about DRM Susan Landau, Renee Stratulate, and Doug Twilleager Sun Microsystems email: susan.landau, renee.stratulate, doug.twilleager @sun.com March 14, 2006 Abstract Digitization and the Internet bring the movie industry essentially free distribution for home viewing but also an increased capability to copy. Through legislation and technology the industry has been seeking to fully control usage of the bits it creates; their model is “restrictive” digital-rights management (rDRM) that only allows the user to view the film rather than copy, edit, or create new content. From a business perspective, this type of digital-rights management (DRM) may be the wrong model. Recent analyses show a drop in movie attendance and an increase in participatory leisure-time activities fueled by the Internet[25]. One specific such is MMORPGs, massive multi-player online role-playing games. In MMORPGs, players exercise design technologies and tools that further their roles and play. While MMORPGs are relatively new, the role-playing games follow a long tradition of participatory fandom[16]. The wide-spread participatory behavior of MMORPG players is unlikely to be a transient phenomenon. The experience that the Internet generation has of interacting with, rather than consum- ing, content, could be the basis for a new business for Hollywood: films that enable users to interact directly by putting themselves (and others) into the movie. Increased quality of rendering makes such creations a real possibility in the very near future. In this paper we argue distribution using non-restrictive, or flexible, digital-rights 1 management could create new business for Hollywood and is in the industry’s economic interest. -

In the Archives Here As .PDF File

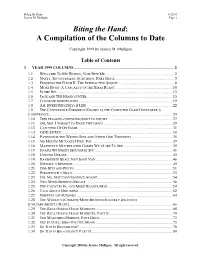

Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 1 Biting the Hand: A Compilation of the Columns to Date Copyright 1999 by Jessica M. Mulligan Table of Contents 1 YEAR 1999 COLUMNS ...................................................................................................2 1.1 WELCOME TO MY WORLD; NOW BITE ME....................................................................2 1.2 NASTY, INCONVENIENT QUESTIONS, PART DEUX...........................................................5 1.3 PRESSING THE FLESH II: THE INTERACTIVE SEQUEL.......................................................8 1.4 MORE BUGS: A CASUALTY OF THE XMAS RUSH?.........................................................10 1.5 IN THE BIZ..................................................................................................................13 1.6 JACK AND THE BEANCOUNTER....................................................................................15 1.7 COLOR ME BONEHEADED ............................................................................................19 1.8 AH, SWEET MYSTERY OF LIFE ................................................................................22 1.9 THE CONFERENCE FORMERLY KNOWN AS THE COMPUTER GAME DEVELOPER’S CONFERENCE .........................................................................................................................24 1.10 THIS FRAGGED CORPSE BROUGHT TO YOU BY ...........................................................27 1.11 OH, NO! I FORGOT TO HAVE CHILDREN!....................................................................29 -

IGDA Online Games White Paper Full Version

IGDA Online Games White Paper Full Version Presented at the Game Developers Conference 2002 Created by the IGDA Online Games Committee Alex Jarett, President, Broadband Entertainment Group, Chairman Jon Estanislao, Manager, Media & Entertainment Strategy, Accenture, Vice-Chairman FOREWORD With the rising use of the Internet, the commercial success of certain massively multiplayer games (e.g., Asheron’s Call, EverQuest, and Ultima Online), the ubiquitous availability of parlor and arcade games on “free” game sites, the widespread use of matching services for multiplayer games, and the constant positioning by the console makers for future online play, it is apparent that online games are here to stay and there is a long term opportunity for the industry. What is not so obvious is how the independent developer can take advantage of this opportunity. For the two years prior to starting this project, I had the opportunity to host several roundtables at the GDC discussing the opportunities and future of online games. While the excitement was there, it was hard not to notice an obvious trend. It seemed like four out of five independent developers I met were working on the next great “massively multiplayer” game that they hoped to sell to some lucky publisher. I couldn’t help but see the problem with this trend. I knew from talking with folks that these games cost a LOT of money to make, and the reality is that only a few publishers and developers will work on these projects. So where was the opportunity for the rest of the developers? As I spoke to people at the roundtables, it became apparent that there was a void of baseline information in this segment. -

Annotated Worlds for Animate Characters

ANNOTATED WORLDS FOR ANIMATE CHARACTERS a dissertation submitted to the department of computer science and the committee on graduate studies of stanford university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy Patrick Owen Doyle March 2004 c Copyright by Patrick Owen Doyle 2004 All Rights Reserved ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Richard Fikes (Principal Adviser) I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Barbara Hayes-Roth I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Terry Winograd Approved for the University Committee on Graduate Studies. iii Abstract Autonomous intelligent agents designed to appear as convincing “animate” characters are presently quite limited. How useful and how believable they are depends on the extent to which they are integrated into a specific environment for a particular set of tasks. This tight integration of character and context is an inadequate approach in the rapidly-expanding realm of large, diverse, structurally homogeneous but dis- parate virtual environments, of which the Web is only the most obvious example. By separating a character’s core features, which are invariable, from its knowledge of and abilities in any specific environment, and embedding this latter information in the environment itself, we can significantly improve the character’s believability, its utility, and its reusability across a variety of domains. -

Modelos De Negocios En La Industria Del Videojuego : Análisis De Caso De

Universidad de San Andrés Escuela de Negocios Maestría en Gestión de Servicios Tecnológicos y Telecomunicaciones Modelos de negocios en la industria del videojuego : análisis de caso de Electronics Arts Autor: Weller, Alejandro Legajo : 26116804 Director/Mentor de Tesis: Neumann, Javier Junio 2017 Maestría en Servicios Tecnológicos y Telecomunicaciones Trabajo de Graduación Modelos de negocios en la industria del videojuego Análisis de caso de Electronics Arts Alumno: Alejandro Weller Mentor: Javier Neumann Firma del mentor: Victoria, Provincia de Buenos Aires, 30 de Junio de 2017 Modelos de negocios en la Industria del videojuego Abstracto Con perfil bajo, tímida y sin apariencia de llegar a destacarse algún día, la industria del videojuego ha revolucionado a muchos de los grandes participantes del mercado de medios instalados cómodamente y sin preocupaciones durante muchos años. Los mismos nunca se imaginaron que en tan poco tiempo iban a tener que complementarse, acompañar y hasta temer en muchísimos aspectos a este nuevo actor. Este nuevo partícipe ha generado en solamente unas décadas de vida, una profunda revolución con implicancias sociales, culturales y económicas, creando nuevos e interesantes modelos de negocio los cuales van cambiando en períodos cada vez más cortos. A diferencia del crecimiento lento y progresivo de la radio, el cine y luego la televisión, el videojuego ha alcanzado en apenas medio siglo de vida ser objeto de gran interés e inversión de diferentes rubros, y semejante logro ha ido creciendo a través de transformaciones, aceptación general y evoluciones constantes del concepto mismo de videojuego. Los videojuegos, como indica Provenzo, E. (1991), son algo más que un producto informático, son además un negocio para quienes los manufacturan y los venden, y una empresa comercial sujeta, como todas, a las fluctuaciones del mercado. -

Electronic Arts 20 01 Ar

ELECTRONIC ARTS ELECTRONIC ARTS 209 REDWOOD SHORES PARKWAY, REDWOOD CITY, CA 94065-1175 www.ea.com AR 01 20 TO OUR S T O C K H O L D E R S Fiscal year 2001 was both a challenging and exciting period for our company and for the industry. The transition fr om the current generation of game consoles to next generation systems continued, marked by the debut of the first entry in the next wave of new technology – the PlayStation®2 computer entertainment system from Sony. Nintendo and Microsoft will launch new platforms later this year, creating unprecedented levels of competition, cr eativity and excitement for consumers. Most importa n t l y , this provides a unique opportunity for Electron i c A rts to drive revenue and profi t growth as we move through the next technology cycle. In conjunction with steady increases in the PC market, plus the significant new opportunity in online gaming, we believe Electron i c Ar ts is poised to achieve new levels of success and leadership in the interactive entertainment category. In FY01, consolidated net revenue decreased 6.9 percent to $1,322 million. As a result of our investment in building the leading Internet gaming website, consolidated net income decreased $128 million to a consoli- dated net loss of $11 million, while consolidated diluted earnings per share decreased $0.96 to a diluted loss per share of $0.08. Pro forma consolidated net income and earnings per share, excluding goodwill, non-cash and one-time charges were $6 million and $0.04, res p e c t i v e l y , for the year. -

View Annual Report

EA 2000 AR 2000 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Fiscal years ended March 31, 2000 1999 % change (In millions, expect per share data) Net Revenues $1,420 $1,222 16 % Operating Income 154 105 47 % Net Income 117 73 60 % Diluted Earnings Per Share 1.76 1.15 53 % Operating Income* 172 155 11 % Pro-Forma Net Income* 130 114 14 % Pro-Forma Diluted EPS* 1.95 1.81 8 % Working Capital 440 333 32 % Total Assets 1,192 902 32 % Total Stockholders’ Equity 923 663 39 % 2000 PRO-FORMA CORE FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Fiscal years ended March 31, 2000 1999 % change (In millions, expect per share data) Net Revenues $ 1,401 $1,206 16 % Operating Income 208 114 82 % Net Income 154 79 95 % Pro-Forma Net Income* 164 120 37 % $ $1,420 1.95 $1,401 $130 $1.81 $1,222 $1,206 $164 $114 $909 $1.19 $898 $120 $73 $74 98 99 00 98 99 00 98 99 00 98 99 00 98 99 00 Consolidated Consolidated Pro-Forma Consolidated Pro-Forma Pro-Forma Core Pro-Forma Core Net Revenues Net Income* Diluted EPS* Net Revenues Net Income* (In millions) (In millions) (In millions) (In millions) FISCAL 2000 OPERATING HIGHLIGHTS • 16 percent increase in EA core net revenues • Signed agreement to be exclusive provider of games • 37 percent increase in EA core net income* on AOL properties • 69 titles released: • Acquired: ™ – 30 PC –DreamWorks Interactive ™ – 30 PlayStation –Kesmai –8 N64 –PlayNation –1 Mac * EXCLUDES GOODWILL AND ONE-TIME ITEMS IN EACH YEAR. AR 2000 EA CHAIRMAN’S LETTER TO OUR STOCKHOLDERS During fiscal year 2000 Electronic Arts (EA) significantly enhanced its strategic position in the interactive entertainment category. -

Crowdfunding Your Game Company Via a Title III/Reg CF Raise (Consumer Equity Crowdfunding)

Crowdfunding Your Game Company via a Title III/Reg CF Raise (Consumer Equity Crowdfunding) Gordon Walton President, ArtCraft Entertainment, Inc. What We’ll Cover Today ● Who am I? ● Equity Crowdfunding Overview ● Statistics on Title III Raises ● Preparing your Raise ● Executing your Raise ● Closing your Raise ● Ongoing Shareholder Communication ● Summary ● Q&A Gordon Walton ● First commercial computer game in 1977 (Trek-X for the Pet 2001) ● First indie company 1984-89 building 20 games (Shard of Spring, Gato, Sub Battle Simulator, PT-109, Reader Rabbit, The Playroom, NFL Challenge, Harpoon, more…) ● Went “corporate” in 1989, working for Three-Sixty Pacific, Konami, GameTek, Alliance Interactive, Kesmai, Electronic Arts (Origin and Maxis), Sony Online Entertainment, Electronic Arts (BioWare) ● Currently an “Indie” building the MMO Crowfall® Equity Crowdfunding Overview ● Rewards Crowdfunding .vs. Equity Crowdfunding ● What is a Title III/Reg CF offering? ● How is this different than a Reg D (VC or Angel Investor) offering? ● Working with a portal ● Communication restrictions Statistics on Title III Raises Close day stats ● $669,497 and over 1,200 investors ● 9th largest Title III/Reg CF investment out of ~142 starts and 74 reaching minimum funding ● Our raise was ~3.6% of all Title III money to date ● We raised 70% of all Title III money in our last week of the raise ● We raised more than the other 3 Indiegogo launch titles combined (games are hot!) Preparing Your Raise ● Picking an Attorney ● Picking a Portal to Work With ● Preparing -

Game Developer

T H E L E A D I N G G A M E I N D U S T R Y MAGAZINE vo L 1 8 N o 8 se p tem b er 2 0 1 1 I N S I D E : intelligent c ameras S w o rd & S w o R c ery p o STM o RTEM The best ideas evolve. Great ideas don’t just happen. They evolve. Your own development teams think and work fast. Don’t miss a breakthrough. Version everything with Perforce. Software and firmware. Digital assets and games. Websites and documents. More than 5,000 organizations and 350,000 users trust Perforce SCM to version work enterprise-wide. Try it now. Download the free 2-user, non-expiring Perforce Server from perforce.com Or request an evaluation license for any number of users. Perforce Video Game Game Developer page ad.indd 1 06/07/2011 19:14 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE VOL18 NO5 CONTENTS.0911 VOLUME 18 NUMBER 08 MAYM A Y 20112 0 1 1 INSIDE: BROWSER TECH MEGA-ROUNDUP DEPARTMENTS 2 GAME PLAN By Brandon Sheffield [EDITORIAL] The Portable Future 4 HEADS UP DISPLAY [NEWS] The Difference Initiative, HALO 2600 Source Code Released, and Flashback, Recipes, and Zombies POSTMORTEM 31 TOOL BOX By Bradley Meyer [REVIEW] Soundminer HD 14 SECTION 8: PREJUDICE With SECTION 8: PREJUDICE, TimeGate took what was planned as a 35 THE INNER PRODUCT By Nick Darnell [PROGRAMMING] console game and presented it as a $15 downloadable title. Not only Automated Occluders for GPU Culling did the team have to change its way of thinking about pricing and presentation, it also had to work out how to shrink assets and scale 42 THE BUSINESS By David Edery [BUSINESS] the design appropriately to fit within the download limit. -

Download 860K

Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 1 Biting the Hand: A Compilation of the Columns to Date Copyright 2001 by Jessica M. Mulligan Copyright 2000 by Jessica Mulligan. All right reserved. Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 2 Table of Contents 1 THE 1997 COLUMNS......................................................................................................6 1.1 ISSUE 1: APRIL 1997.....................................................................................................6 1.1.1 ACTIVISION??? WHO DA THUNK IT? .............................................................7 1.1.2 AMERICA ONLINE: WILL YOU BE PAYING MORE FOR GAMES?..................8 1.1.3 LATENCY: NO LONGER AN ISSUE .................................................................12 1.1.4 PORTAL UPDATE: December, 1997.................................................................13 1.2 ISSUE 2: APRIL-JUNE, 1997 ........................................................................................15 1.2.1 SSI: The Little Company That Could..................................................................15 1.2.2 CompuServe: The Big Company That Couldn t..................................................17 1.2.3 And Speaking Of Arrogance ...........................................................................20 1.3 ISSUE 3 ......................................................................................................................23 1.3.1 December, 1997.................................................................................................23