The Health of Canada's Children: a CICH Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

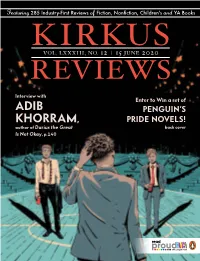

Kirkus Reviews

Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS Interview with Enter to Win a set of ADIB PENGUIN’S KHORRAM, PRIDE NOVELS! author of Darius the Great back cover Is Not Okay, p.140 with penguin critically acclaimed lgbtq+ reads! 9780142425763; $10.99 9780142422939; $10.99 9780803741072; $17.99 “An empowering, timely “A narrative H“An empowering, timely story with the power to experience readers won’t story with the power to help readers.” soon forget.” help readers.” —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews, starred review A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION WINNER OF THE STONEWALL A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION BOOK AWARD WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL 9780147511478; $9.99 9780425287200; $22.99 9780525517511; $8.99 H“Enlightening, inspiring, “Read to remember, “A realistic tale of coming and moving.” remember to fight, fight to terms and coming- —Kirkus Reviews, starred review together.” of-age… with a touch of —Kirkus Reviews magic and humor” A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION —Kirkus Reviews Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s,and YA Books. KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS THE PRIDEISSUE Books that explore the LGBTQ+ experience Interviews with Meryl Wilsner, Meredith Talusan, Lexie Bean, MariNaomi, L.C. Rosen, and more from the editor’s desk: Our Books, Ourselves Chairman HERBERT SIMON BY TOM BEER President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # As a teenager, I stumbled across a paperback copy of A Boy’s Own Story Chief Executive Officer on a bookstore shelf. Edmund White’s 1982 novel, based loosely on his MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] coming-of-age, was already on its way to becoming a gay classic—but I Editor-in-Chief didn’t know it at the time. -

Adolescent Female Embodiment As a Transformational Experience in the Lives of Women: an Empirical Existential- Phenomenological Investigation Allyson Havill

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 2006 Adolescent Female Embodiment As A Transformational Experience In The Lives of Women: An Empirical Existential- Phenomenological Investigation Allyson Havill Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Havill, A. (2006). Adolescent Female Embodiment As A Transformational Experience In The Lives of Women: An Empirical Existential-Phenomenological Investigation (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/ 639 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adolescent Female Embodiment as Transformational Experience in the Lives of Women: An Empirical Existential-Phenomenological Investigation A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Psychology Department McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Allyson Havill March 31, 2006 Paul Richer, Ph.D. Anthony Barton, Ph.D. Eva Simms, Ph.D. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE 9 Phenomenological Theories of the Body 9 The Body and Adolescent Development 19 Contemporary Theories -

ARIA Charts, 1992-01-03 to 1992-03-08

AUSTRALIAN TOP 50 A A TRADE MARK REGD. THE AUSTRALIAN RECORD INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION LTD. SINGLES CHART PROUDLY BROUGHT TO YOU BY YOUR BOTTLER OF 'COCA—COLA' 1991 TITLE/ARTIST Co. Cat. No. STATE CHARTS 1 (EVERYTHING I DO) I DO IT FOR YOU Bryan Adams A2 PDR/POL 390 639-4 New South Wales 2 TINGLES (EP) Ratcat A roo/POL 878 165-4 1 (Everything I Do) I Do It For You 3 GREASE MEGAMIX Olivia Newton-John & John Travolta A PDR/POL 879 410-4 2 Tingles (EP) 4 THE HORSES Daryl Braithwaite A COLUMBIA 656617 4 3 The Horses GEF/BMG GEFCS 19039 4 More Than Words 5 YOU COULD BE MINE Guns n' Roses A 5 Grease Megamix 6 READ MY LIPS Melissa A PHON/POL 868 424-4 6 Read My Lips 7 MORE THAN WORDS Extreme A PDR/POL 390 634-4 7 You Could Be Mine 8 I'VE BEEN THINKING ABOUT YOU Londonbeat A ANX/BMG CSANX 0014 8 I've Been Thinking About You 9 JOYRIDE Roxette A EMI 2547-4 9 Better 101'm Too Sexy 10 THE SHOOP SHOOP SONG (IT'S IN HIS KISS) Cher A EPIC 656666 4 11 DO THE BARTMAN The Simpsons • GEF/BMG 543919665-4 Victoria & Tasmania 12 UNFORGETTABLE Natalie Cole With Nat "King" Cole • WARNER 755964875-4 1 (Everything I Do) I Do It For You 13 I'M TOO SEXY R.S.F. (Right Said Fred) A LIB/FES C 10503 2 Grease Megamix 14 LOVE ... WILL BE DONE Martika A COLUMBIA 656975 4 3 Tingles (EP) VIR/EMI VOZC 094 4 Read My Lips 15 I TOUCH MYSELF Divinyls A 5 I've Been Thinking About You 16 RUSH Big Audio Dynamite II • COLUMBIA 656978 4 6 More Than Words 17 FANTASY Black Box • BMG CS 3895 1 You Could Be Mine 18 RHYTHM OF MY HEART Rod Stewart • WARNER 543919374-4 8 The Horses 19 RUSH RUSH Paula Abdul • VIR/EMI VUSC 38 9 Joyride 10 Fantasy 20 BETTER The Screaming Jets • roo/POL 878 814-4 21 I WANNA SEX YOU UP Color Me Badd • WARNER 543919382-4 Queensland 22 ICE ICE BABY Vanilla Ice A EMI 2504-4 1 (Everything I Do) I Do It For You 23 SADNESS PART 1 Enigma • VIR/EMI DINSC 101 2 The Horses 24 HERE I AM (COME AND TAKE ME) UB40 • VIR/EMI TCDEPC 34 3 The Shoop Shoop Song (It's In His Kiss) LIB/FES C 10380 4 You Could Be Mine 25 3 A.M. -

Morcheeba David & the Citizens Speedy J Masayah Paris Joppe

Nummer 5 • 2002 | Sveriges största musiktidning Morcheeba David & the Citizens Speedy J Masayah Paris Joppe Pihlgren Groove 5 • 2002 Ledare Chefredaktör & ansvarig utgivare Gary Andersson, [email protected] Skivredaktör Vintern är Per Lundberg Gonzalez-Bravo, [email protected] Bokredaktör Dan Andresson, [email protected] Speedy J sid. 5 långt borta Bildredaktör En fråga till Joppe Pihlgren sid. 5 Johannes Giotas, [email protected] Det enda jag är intresserad av just nu är somma- Layout Inget förskräckt våp sid. 5 ren. Dagarna är långa och solstinna, fotbolls- Henrik Strömberg, [email protected] Paris sid. 6 VM är äntligen igång och musikfestivalerna känns extremt lockande. Dessutom har det kom- Redigering Skivlangning i förtid sid. 6 mit en hel del kanonplattor den senaste månaden Gary Andersson, Henrik Strömberg (om du inte hittar recensionerna i pappers-Groove Masayah sid. 7 så finns de på www.groove.st). Annonser Ett subjektivt alfabet sid. 7 Just resorna till festivaler känns sommarlov. Per Lundberg G.B. Bilen/tåget/bussen tar dig ut på äventyr i världen Distribution David & the Citizens sid. 9 vare sig det innebär Småland eller utlandet. Helt Karin Stenmar, [email protected] Morcheeba sid. 11 plötsligt befinner man sig i ett sammanhang utan regler där dina enda åtaganden är att ha roligt Web Primal Scream sid. 12 tre dygn i rad tillsammans med dina vänner. Rätt Ann-Sofie Henricson, Henrik Ragnevi okej förutsättningar. Kanske inmundigas även Bokrecensioner sid. 16 alkoholhaltiga drycker. Som grädde på det moset Groovearbetare Albumrecensioner sid. 19 kan du även se oräkneliga band om du orkar Mats Almegård Björn Magnusson hasa dig från campingområdet. -

Sick As a Dog Aimed at the Creative Crowd

INSIDE: GET THE RIGHT RESULTS WITH OUR CLASSIFIEDS SECTION Yo u r Neighborhood — Yo u r News® BrooklynPaper.com • (718) 260–2500 • Brooklyn, NY • ©2015 Serving Brownstone Brooklyn, Williamsburg & Greenpoint AWP/14 pages • Vol. 38, No. 42 • October 16–22, 2015 • FREE TECH, TECH, BOOM! TO PETWARNING OWNERS! Developers banking on Bushwick as next big startup hub By Allegra Hobbs The Brooklyn Paper The new Silicon Alley will really live up to its name. Bushwick is still in its first trimes- ter of gentrification but developers are already snapping up massive neighbor- hood warehouses to convert into trendy offices for what they hope will become New York’s next big startup scene. “We think it’s the place to go,” said Jim Stein, vice president of developer Lincoln Property Co., which recently bought a six-story former coffee-roast- ing warehouse on Jefferson Street at Cy- press Avenue for $46 million, which it plans on turning into an office complex dubbed the Jefferson. The pitch to potential tenants is that hordes of creative types — known in real-estate jargon as “tech, advertising, media, and information” workers — are already living in the neighborhood, and they can set up shop at cheaper rates than Manhattan or Dumbo, right in the middle of the employment marketplace. Developers are turning a former Jefferson Street coffee-roasting warehouse into an opulent office build- “The Jefferson is a once in a gen- ing for tech types who prefer green cabs over Ubers. eration opportunity for TAMI tenants searching for an exceptional Brook- lyn branding opportunity,” Stein said nowned street art .” you don’t have enough space [to work],” facturing, which took over a chunk of in a promotional release. -

On Trial for Patron Killing Story on Paflt I OHIO Statt .MOSSM LIBRABT • 13T8 * BIOS ST

7' ' '"". : '"."• . .- ... .-• yWg4»M>'*^. r'rtffr*** ^^' -.» V-V* «»> On Trial For Patron Killing Story On Paflt I OHIO STATt .MOSSM LIBRABT • 13T8 * BIOS ST. • ,-• . • • •. ; THE QHW C0UU»BU3, 0B10 * . • - - ** , Ifcl CHAMPION - • «. mmmm • * • ,... ,.,1..,..,—..... • • • i • . • •.. -. * yOU 11, No. fcl m SATURDAY, JUNE 4„ 1960 ? 20 CENTS COLUMBUS, OHIO H - - • . Story On Page 3 . • • j • iA fi r • •'''-•- • • ... • •• • ' Story On Page 3 • • . • v af| - ... i.~... •' i • " " " 5!or On P s 2 : NAACP SPIRIT ABROAD • . ' • • • .. •• i r . ?; '. FIRST PICKET LINE o! Wootworth outside the Continental If. S. occurred in Santurce, Puerto Rico, according to Charles S. Zlmmornian, member of the national advisory committee of CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) which has been coordinat ing the picketing, and vice president of the International Ladies ' EX-HEAVYWEIGHT BOXING champ Joe Louis is shown as he arrived in Cuba for the re Garment Workers Union. Local 800 of the anion sponsored the cent New Year*s celebration to which several ne vsmen and public relations persons were invited picket line. Sign says, "Don't Buy In Wool worth Stores" and x^ n»:*ke an inspection of tourists* accommodatio is and life in Cuba. He denies reports he Is tied For Equal Human Rights." xuih I Ucl Ca^o. • , L > I ' > iy ->^-*#-^«V4*iV*»"'_ *»f? 'f SATURDAY, JUNE 4, 1960 THE OHIO SENTINEC PACK % - 51£ SATURDAY. JUNE < 1S60 • | THE OHIO 8ENTINBU._ PAGE 2 Heat Over Cuba Brings Joe Louis Threat To Quit Agency Columbus NAACP Pushes Picketing By TED COLEMAN ley secured a contract to attract agency has a similar contract the daily press which reported beeu defending his position '»a. -

March 01, 1991 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep March 1991 3-1-1991 Daily Eastern News: March 01, 1991 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1991_mar Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: March 01, 1991" (1991). March. 1. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1991_mar/1 This is brought to you for free and open access by the 1991 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in March by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dealing with something everyone faces. Page 7A Iraq accepts conditions of peace plan Kuwaitis, Americans joyous Professors predict peace DHAHRAN, Saudi Arabia (AP) announced a cease-fire in the Gulf - From the Euphrates to the Persian War, Iraq gave in to the coalition's will bolster Bush's popularity Gulf, U.S. and allied troops held ·conditions for suspending military By LAURA DURNELL theirfire along a smoldering battle action after making several previ Features editor • A local group plans front Thursday, weary, muddy but ous peace offers that the allies con victorious in a lightning war that sidered unacceptable. services Friday for war It looks like George Bush might freed Kuwait and humbled Iraq. As a cease-fire dawned on the dead. Page 3A • Kuwait says Iraq still have made his niche in history. Statesmen began what President . 43rd day of the conflict, American holding some civilians, At least, that's what one political • Guns sales on the rise Bush called "the difficult task" of paratrooper David Hochins had a POWs. -

Minority Target Class Detection for Short Text Classification by Fatima Chiroma

Minority Target Class Detection for Short Text Classification by Fatima Chiroma The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth January 2021 To the memory of my father. ii Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Parts of the work presented in this thesis draws from the following publications: • Fatima Chiroma, Han Liu, and Mihaela Cocea. Text classification for suicide re- lated tweets. In 2018 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernet- ics (ICMLC), volume 2, pages 587–592. IEEE, 2018. (Chapter 3) • Fatima Chiroma, Han Liu, and Mihaela Cocea. Suicide related text classification with prism algorithm. In 2018 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics (ICMLC), volume 2, pages 575-580. IEEE, 2018. (Chapter 3) • Fatima Chiroma, Mihaela Cocea, and Han Liu. Detection of suicidal Twitter posts. In UK Workshop on Computational Intelligence, pages 307–318. Springer, 2019. (Chapter 3) • Fatima Chiroma and Ella Haig. Disambiguation of features for improving target class detection from social media text. In Proceedings of the IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence (WCCI) 2020. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2020. (Chapter 4) Fatima Chiroma January 2021 iii Abstract The rise of social media has resulted in large and socially relevant informational con- tents, and unhealthy behaviours such as cyberbullying, suicidal ideation and hate speech. -

The Gamut Archives Publications

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU The Gamut Archives Publications Fall 1986 The Gamut: A Journal of Ideas and Information, No. 19, Fall 1986 Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/gamut_archives Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Cleveland State University, "The Gamut: A Journal of Ideas and Information, No. 19, Fall 1986" (1986). The Gamut Archives. 17. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/gamut_archives/17 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Gamut Archives by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .-.- .-. A Journal of Ideas Number 19 Fall, 1986 $5.00 and Information ~I AND ~"A CLEV :Y UNIV NOV 7 '986 • remlum To show our appreciation of your long-term commitment to The Gamut, we have reprinted seven of our articles about Cleveland in a paperback called The Gamut Looks at Cleveland. It is yours, free, if you renew at the Lifetime ($100) or three-year rate ($25). Don't miss this excellent opportunity The Gamut Looks at Cleveland: • Cemeteries in Cleveland, 1797-1984 • Severance Hall • Geoffrion's Landmark Complex • Movable Bridges Over the Cuyahoga • Livable Cleveland Houses • The New Mayfield • Cleveland's Terminal Tower THE GAMUT RT 1216 • Cleveland State University Cleveland, Ohio 44115 -- . Number 19 Fall 1986 EDITORIAL Louis T. Milic 3 Gnothi Seauton David M. Larson 5 Science Fiction-Not the Future Despite the claims of some writers, S-F is not prophetic. -

Basic Conduct

WORLD WIDE MINISTRIES Basic Conduct PEOPLE REACHING PEOPLE Don Krider, Director World Wide Ministries "...SPEAKING THE TRUTH IN LOVE…” EPH.4:11-16 BASIC CONDUCT 1 DK BASIC CONDUCT FOREWORD As we begin this study, we need to learn to be disciplined. One thing that God's people haven't been is disciplined and yet the word discipleship means a disciplined one. We set patterns in our lives that make us late to classes, and you will find that carries over into every area in our life, not only our spiritual life, but also our physical life. We are going to begin with the Introduction. It took me awhile to learn that God meant that we could live in the Kingdom of God NOW. We have a problem with the NOW. We can all live in tomorrow land or in yesterday's world, but it is hard for us to get into a relationship with a NOW GOD. We are always saying, "Well, someday, or tomorrow, or this or that," but God wants you to be the people of God today, representing Jesus Christ in your everyday living. The Kingdom of God in Romans 14:17 simply states this: "It is not meat nor drink, but it is righteousness and peace and joy in the Holy Ghost." Two things are here: the Lord tells us what the Kingdom of God is and where it is. The Holy Ghost is not something to come; the Holy Ghost is HERE. He was sent two thousand years ago, and now what we have to learn to do is how to press into the Spirit. -

The Pursuit of Happiness Love Junk Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Pursuit Of Happiness Love Junk mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Love Junk Country: US Released: 1988 Style: Alternative Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1615 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1421 mb WMA version RAR size: 1189 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 771 Other Formats: TTA AU VOX AA MP4 XM DXD Tracklist A1 Hard To Laugh 2:39 A2 Ten Fingers 2:52 A3 I'm An Adult Now 4:30 A4 She's So Young 3:36 A5 Consciousness Raising As A Social Tool 2:33 A6 Walking In The Woods 3:52 B1 Beautiful White 3:29 B2 When The Sky Comes Falling Down 3:29 B3 Looking For Girls 2:51 B4 Man's Best Friend 2:38 B5 Tree Of Knowledge 3:55 B6 Killed By Love 4:04 Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Chrysalis Records, Inc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Chrysalis Records, Inc. Lacquer Cut At – Sterling Sound Credits Bass – Johnny Sinclair Drums – Dave Gilby Engineer – Todd Rundgren Guitar, Vocals – Kris Abbott, Moe Berg Mastered By – Greg Calbi Mixed By – Todd Rundgren Producer – Todd Rundgren Vocals – Leslie Stanwyck Written-By – Moe Berg Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 044114167518 Matrix / Runout (Side 1 runout, etched/stamped): FV41675 A - RE1 C21 : G1 A24 STERLING ☒☒☒☒☒☒☒☒☒☒☒☒☒☒ Matrix / Runout (Side 2 runout, etched/stamped): FV41675 - B - RE1 C1 : G1 C4 STERLING Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Pursuit Of CHR 1675 Love Junk (LP, Album) Chrysalis CHR 1675 Canada 1988 Happiness The Pursuit Of 64 3216751 Love Junk (LP, Album) Chrysalis 64 3216751 Italy 1988 Happiness The Pursuit Of Love Junk (Cass, CHSC-41675