World Chronicle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peacekeeping: the Way Ahead?

INSTITUTEFOR NATIONAL STRATEGICSTUDIES PEACEKEEPING: THE WAY AHEAD? Contributors William H. Lewis John Mackinlay John G. Ruggie Sir Brian Urquhart Editor William H. Lewis NATIONAL DEFENSE UNIVERSITY McNair Paper 25 A popular Government, without popular information or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy; or perhaps both. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance; And a people who mean to be their own Go vernors, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives. JAMES MADISON to W. T. BARRY August 4, 1822 PEACEKEEPING: THE WAY AHEAD? Report of a Special Conference Contributors William H. Lewis John Mackinlay John G. Ruggie Sir Brian Urquhart Editor William H. Lewis McNair Paper 25 November 1993 INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL STRATEGIC STUDIES NATIONAL DEFENSE UNIVERSITY Washington, D.C. NATIONAL DEFENSE UNIVERSITY [] President: Lieutenant General Paul G. Cerjan [] Vice President: Ambassador Howard K. Walker INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL STRATEGIC STUDIES rn Acting Director: Stuart E. Johnson Publications Directorate [] Fort Le, ley J. McNair [] Washington, D.C. 20319--6000 [] Phone: (202) 475-1913 [] Fax: (202) 475-1012 [] Director: Frederick T. Kiley [] Deputy Director: Lieutenant Colonel Barry McQueen [] Chief, Publications Branch: George C. Maerz [] Editor: Mary A. SommerviUe 12 Secretary: Laura Hall [] Circulation Manager: Myma Morgan [] Editing: George C. Maerz [] Cover Design: Barry McQueen From time to time, INSS publishes short papers to provoke thought and inform discussion on issues of U.S. national security in the post-Cold War era. These monographs present current topics related to national security strategy and policy, defense resource man- agement, international affairs, civil-military relations, military technology, and joint, com- bined, and coalition operations. -

Black History Month Activity

Black History Month How to do it: In advance, prepare a set of facts about Black History Month so that you have one fact for each student. 1 Introduce the activity: “In honor of Black His- tory Month, we’re going to share interesting Black History Month facts about important African Americans in Dr. Charles Drew was an American surgeon whose Jackie Robinson was the first African American to pioneering research in blood transfusions saved play major league baseball in the 20th century. thousands of lives in World War II. He also U.S. history.” invented what are now known as bloodmobiles. Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery. She Toni Morrison is a writer and editor. then led many more slaves to freedom on She was the first African-American woman the Underground Railroad. to win the Nobel Prize in literature. In 2008, Barack Obama became the first African W.E.B. DuBois was a scholar 2 Explain how to do the activity: “Everyone will American president of the United States. who co-founded the NAACP in 1909. Alvin Ailey started a modern dance company Katherine G. Johnson solved hard math get one fact. When I say ‘Go,’ mix and mingle in 1958. It has performed for millions problems at NASA. Her work helped put of people around the world. astronauts into space. until I say ‘Stop.’ Then pair up with someone Mae Jemison is an American astronaut and physician. She was the first African American woman In 1955, Marian Anderson became in NASA’s astronaut training program, and she the first African American to sing with the became the first African American to travel into space New York Metropolitan Opera. -

Operation Market Garden WWII

Operation Market Garden WWII Operation Market Garden (17–25 September 1944) was an Allied military operation, fought in the Netherlands and Germany in the Second World War. It was the largest airborne operation up to that time. The operation plan's strategic context required the seizure of bridges across the Maas (Meuse River) and two arms of the Rhine (the Waal and the Lower Rhine) as well as several smaller canals and tributaries. Crossing the Lower Rhine would allow the Allies to outflank the Siegfried Line and encircle the Ruhr, Germany's industrial heartland. It made large-scale use of airborne forces, whose tactical objectives were to secure a series of bridges over the main rivers of the German- occupied Netherlands and allow a rapid advance by armored units into Northern Germany. Initially, the operation was marginally successful and several bridges between Eindhoven and Nijmegen were captured. However, Gen. Horrocks XXX Corps ground force's advance was delayed by the demolition of a bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal, as well as an extremely overstretched supply line, at Son, delaying the capture of the main road bridge over the Meuse until 20 September. At Arnhem, the British 1st Airborne Division encountered far stronger resistance than anticipated. In the ensuing battle, only a small force managed to hold one end of the Arnhem road bridge and after the ground forces failed to relieve them, they were overrun on 21 September. The rest of the division, trapped in a small pocket west of the bridge, had to be evacuated on 25 September. The Allies had failed to cross the Rhine in sufficient force and the river remained a barrier to their advance until the offensives at Remagen, Oppenheim, Rees and Wesel in March 1945. -

A Guide to a Career with the United Nations

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs A Guide to a Career with the United Nations United Nations / New York Table of Contents Acknowledgements Forward Part One: The United Nations Chapter 1: An Overview 1.1-Background Information 1.2-The United Nations System -Official Languages -General Assembly -International Court of Justice -Economic and Social Council -Security Council -Trusteeship Council -Secretariat 1.3-Recent Trends -Co-ordination -Social and Economic Development -Peace and International Security -Human Rights and Humanitarian Assistance -Reorganisation of the Secretariat -UN Budget -UN Competencies for the Future Part Two: Job Opportunities in the United Nations Chapter 2: Opportunities in the Secretariat 2.1-Introduction -Organisational Structure -Staff Regulations -Salary System 2.2-Job Opportunities -Internship Programme -Associate Expert Programme -Consultants and Expert Contracts 2.3 Language-Related Positions -Translators and Interpreters -Language Instructors 2.4 National Recruitment Examination 2.5 Recruitment for Higher Level Positions 2.6 Recruitment for Peacekeeping Missions 2 Chapter 3: Opportunities in Affiliated Agencies 3.1-Introduction 3.2-Opportunities in the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) - Introduction - Internship Programme - Junior Professional Officers (JPO) - Management Training Programme (MTP) 3.3- Opportunities in the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) - Introduction - Internship Programme - Junior Professional Officers (JPO) 3.4- United Nations Volunteers (UNV) -Introduction -

Ralph Bunche House Designation Report

Landmarks Preservation Commission May 17, 2005, Designation List 363 LP-2175 RALPH BUNCHE HOUSE, 115-24 Grosvenor Road, Kew Gardens, Queens. Built, 1927; Architects, Koch & Wagner. Landmark Site: Borough of Queens Tax Map Block 3319, Lot 18. On May 17, 2005, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Ralph Bunche House and its related Landmark Site (Item No. 1). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. There were five speakers in favor of designation, including Dr. Benjamin Rivlin, Chairman Emeritus of the Ralph Bunche Institute, Marjorie Tivin representing the New York City Commission to the United Nations, the Chair of the Community Board 9, and representatives of the Landmarks Conservancy and the Historic Districts Council. Three representatives of the Kew Gardens Civic Association spoke in opposition to designation because they wanted the entire Kew Gardens area designated as an historic district rather than just one building. The owner of the building said he was “ambivalent” about designation, because it was already a National Historic Landmark. Summary Dr. Ralph Bunche and his family lived for more than thirty years in a neo-Tudor style residence constructed in 1927 and designed by the prominent Brooklyn architects Koch & Wagner, located in Kew Gardens, Queens. Bunche had an illustrious career in academia, international service and diplomacy, which included the award of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1950 for his role in negotiating armistice settlements between Israel and its Arab neighbors. He helped found, and then worked for the United Nations, first as head of its Trusteeship Division, later as advisor to three different Sectretaries-General. -

Grade 2 Group Activity: Black History Month

e Le rad ve G l 2 Black History Month Group Activity Jackie Robinson was the first African American Charles Drew was a doctor. He created the first to play major league baseball in the 20th century. large blood bank during World War II. Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery. Toni Morrison is a writer and editor. She then led many more slaves to freedom She was the first African-American woman on the Underground Railroad. to win the Nobel Prize in literature. In 2008, Barack Obama became the first W.E.B. DuBois was a scholar African American president of the United States. who co-founded the NAACP in 1909. Alvin Ailey started a modern dance company Katherine G. Johnson solved hard math in 1958. It has performed for millions problems at NASA. Her work helped of people around the world. put astronauts into space. George Washington Carver was a scientist. In 1955, Marian Anderson became He is most famous for creating over 100 the first African American to sing with the inventions based on the peanut. New York Metropolitan Opera. Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus. Thurgood Marshall was the first African This led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott American justice on the U.S. Supreme Court. and helped stop segregation. Jesse Owens was a record-breaking athlete. Ralph Bunche helped form the United Nations He won four gold medals in track and field in the 1940s. He was the first African American in the 1936 Olympics. to win the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1951, Althea Gibson was the first African Frederick Douglass was an author and American tennis player to compete at Wimbledon. -

Challenge Quiz

Name Date BLACK HISTORY MONTH CHALLENGE QUIZ Directions Circle the letter next to the answer that completes the sentence. 1 Phillis Wheatley published a collection of poetry in . a. 1773 b. 1837 c. 1861 2 was an inventor who helped design Washington, D.C. a. Benjamin Banneker b. George Washington Carver c. Frederick Douglass 3 Jean Baptiste Pointe DuSable is considered the father of . a. jazz b. blues c. Chicago 4 In 1909, , along with Robert Peary and a group of Inuit guides, was the first to reach the North Pole. a. Matthew Henson b. Nat Love c. James Beckwourth 5 W. E. B. Du Bois was one of the founders of . a. the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) b. Morehouse College c. the Congressional Black Caucus 6 Garrett Morgan invented gas masks and . a. the automatic trafc light b. the typewriter c. nylon 7 When the Daughters of the American Revolution wouldn’t let her sing in Constitution Hall in 1939, gave a concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. a. Jessye Norman b. Marian Anderson c. Leontyne Price © Houghton Mifin Harcourt BLACK HISTORY MONTH CHALLENGE QUIZ CONTINUED 8 was the first African American to win the Nobel Peace Prize. a. Ralph Bunche b. Martin Luther King Jr. c. Colin Powell 9 was the first African American Supreme Court Justice. a. Booker T. Washington b. Thurgood Marshall c. Clarence Thomas 10 In 1993, won the Nobel Prize for Literature. a. Maya Angelou b. Alex Haley c. Toni Morrison © Houghton Mifin Harcourt Answer Key BLACK HISTORY MONTH CHALLENGE QUIZ Directions Circle the letter next to the answer that completes the sentence. -

Conceptions and Ideologies of the Negro Problem Ralph J

Contributions in Black Studies A Journal of African and Afro-American Studies Volume 9 Special Double Issue: African American Article 6 Double Consciousness 1992 Conceptions and Ideologies of the Negro Problem Ralph J. Bunche Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs Recommended Citation Bunche, Ralph J. (1992) "Conceptions and Ideologies of the Negro Problem," Contributions in Black Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs/vol9/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Afro-American Studies at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Contributions in Black Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bunche: Conceptions and Ideologies of the Negro Problem Ralph J. Bunche CONCEPTIONS AND IDEOLOGIES OF THE NEGRO PROBLEM NOWLEDGEOF RALPH BUNCHE' S PIONEERING workonAfricanAmerican conceptions ofthe world has been largelyconfinedto specialistsin political scienceand K history? Writing in 1940, Bunche and his staff prepared four, detailed memoranda' on black American organizations and ideologies for the monumental Carnegie-Myrdal study, An American Dilemma.' True to design, this larger work succeededinframing discussions on "racerelations" withinandwithoutacademiafor thesubsequenttwodecades. (Andis stilloccasionally employedtodayas aprimarytext by professorswho haveread little else since that time!) In comparing these original memoranda -

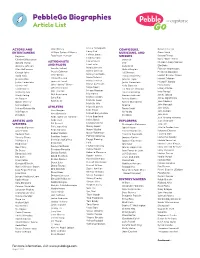

Pebblego Biographies Article List

PebbleGo Biographies Article List Kristie Yamaguchi ACTORS AND Walt Disney COMPOSERS, Delores Huerta Larry Bird ENTERTAINERS William Carlos Williams MUSICIANS, AND Diane Nash LeBron James Beyoncé Zora Neale Hurston SINGERS Donald Trump Lindsey Vonn Chadwick Boseman Beyoncé Doris “Dorie” Miller Lionel Messi Donald Trump ASTRONAUTS BTS Elizabeth Cady Stanton Lisa Leslie Dwayne Johnson AND PILOTS Celia Cruz Ella Baker Magic Johnson Ellen DeGeneres Amelia Earhart Duke Ellington Florence Nightingale Mamie Johnson George Takei Bessie Coleman Ed Sheeran Frederick Douglass Manny Machado Hoda Kotb Ellen Ochoa Francis Scott Key Harriet Beecher Stowe Maria Tallchief Jessica Alba Ellison Onizuka Jennifer Lopez Harriet Tubman Mario Lemieux Justin Timberlake James A. Lovell Justin Timberlake Hector P. Garcia Mary Lou Retton Kristen Bell John “Danny” Olivas Kelly Clarkson Helen Keller Maya Moore Lynda Carter John Herrington Lin-Manuel Miranda Hillary Clinton Megan Rapinoe Michael J. Fox Mae Jemison Louis Armstrong Irma Rangel Mia Hamm Mindy Kaling Neil Armstrong Marian Anderson James Jabara Michael Jordan Mr. Rogers Sally Ride Selena Gomez James Oglethorpe Michelle Kwan Oprah Winfrey Scott Kelly Selena Quintanilla Jane Addams Michelle Wie Selena Gomez Shakira John Hancock Miguel Cabrera Selena Quintanilla ATHLETES Taylor Swift John Lewis Alex Morgan Mike Trout Will Rogers Yo-Yo Ma John McCain Alex Ovechkin Mikhail Baryshnikov Zendaya Zendaya John Muir Babe Didrikson Zaharias Misty Copeland Jose Antonio Navarro ARTISTS AND Babe Ruth Mo’ne Davis EXPLORERS Juan de Onate Muhammad Ali WRITERS Bill Russell Christopher Columbus Julia Hill Nancy Lopez Amanda Gorman Billie Jean King Daniel Boone Juliette Gordon Low Naomi Osaka Anne Frank Brian Boitano Ernest Shackleton Kalpana Chawla Oscar Robertson Barbara Park Bubba Wallace Franciso Coronado Lucretia Mott Patrick Mahomes Beverly Cleary Candace Parker Jacques Cartier Mahatma Gandhi Peggy Fleming Bill Martin Jr. -

Conflict Quartfy Urquhart, Brian. a Life in Peace and War. New York: Harper & Row, 1987

Conflict Quartfy Urquhart, Brian. A Life in Peace and War. New York: Harper & Row, 1987. Brian Urquhart's A Life in Peace and War relates the recollections of a former Under Secretary-General of the United Nations. Except for some early chapters on childhood, Oxford and military service, the work is essentially a description of Urquhart's life in the service of the United Nations. As such the work is a chronicle of the trial and error process with which the UN has been involved since its inception following the Se cond World War. It also details Urquhart's continuing optimism about the organization despite the shedding of many of the naive concepts that he held as a young Secretariat official in 1945. Urquhart's work is written in a lively and energetic style that often proves elusive in the memoirs of international statesmen. No longer claiming status as an international civil servant, Urquhart feels con siderable freedom to criticize a variety of individuals, institutions, coun tries and processes that he maintains have hurt the UN's chances to play a more significant role in the struggle for world peace. They range from Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim to an alcoholic general responsible for UN peacekeeping on the Golan Heights. Urquhart wrote the sections on Waldheim prior to the war crimes allegations currently surrounding the former Secretary-General. He refused to change his text in the aftermath of those allegations and so makes his analysis of Waldheim strictly within the context of the latter's UN service. He also reiterates how deep ly some Israelis seem to have disliked Waldheim, also commented upon in Ezer Weizman's 1981 book The Battle for Peace. -

Dag Hammarskjöld´S Approach to the United Nations and International Law

1 Dag Hammarskjöld´s approach to the United Nations and international law By Ove Bring Professor emeritus of Stockholm University and the Swedish National Defense College Dag Hammarskjöld, the second Secretary‐General of the United Nations, had a flexible approach to international law. On the one hand, he strongly relied on the principles of the UN Charter and general international law, on the other, he used a flexible and balanced ad hoc technique, taking into account values and policy factors whenever possible, to resolve concrete problems. Hammarskjöld had a tendency to express basic principles in terms of opposing tendencies, to apply a discourse of polarity or dualism, stressing for example that the observance of human rights was balanced by the concept of non‐intervention, or the concept of intervention by national sovereignty, and recognizing that principles and precepts could not provide automatic answers in concrete cases. Rather, such norms would serve “as criteria which had to be weighed and balanced in order to achieve a rational solution of the particular problem”.1 Very often it worked. Dag Hammarskjöld has gone to history as an inspiring international personality, injecting a dose of moral leadership and personal integrity into a world of power politics. He succeeded Trygve Lie as Secretary‐General in April 1953, in the midst of the Cold War, and in addition to East‐West rivalry he was confronted with Third World problems and the agonizing birth of the new Republic of Congo, a tumultuous crisis through which he lost his life in the Ndola air crash in September 1961. -

Whose Black Politics? Cases in Post-Racial Black Leadership

Whose Black Politics? Cases in Post-Racial Black Leadership Edited by Andra Gillespie Copyrighted material - provided by Taylor & Francis Frasure-Yokley, University of California, 07/05/2014 First published 2010 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 64" Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2010 Taylor & Francis Typeset in Garamond by EvS Communication Networx, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Gillespie, Andra. Whose Black politics?Copyrighted : cases in post-racial material Black- provided leadership by Taylor/ Andra &Gillespie. Francis p. cm. Frasure-Yokley, University of California, 07/05/2014 Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. African American leadership—Case studies. 2. African Americans—Politics and government—Case studies. 3. African American politicians—Case studies. 4. African Americans—Race identity—Case studies. 5. Post-racialism—United States—Case studies. 6.