Berkeley Apartheid: Unfair Housing in a University Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

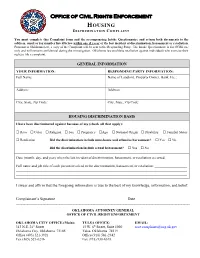

Housing Discrimination Complaint Form

Office of Civil Rights Enforcement HOUSING DISCRIMINATION COMPLAINT You must complete this Complaint form and the accompanying Intake Questionnaire and return both documents to the address, email or fax number listed below within one (1) year of the last incident of discrimination, harassment or retaliation. Pursuant to Oklahoma law, a copy of the Complaint will be sent to the Responding Party. The Intake Questionnaire is for OCRE use only and will remain confidential during the investigation. Oklahoma law prohibits retaliation against individuals who exercise their right to file a complaint. GENERAL INFORMATION YOUR INFORMATION: RESPONDING PARTY INFORMATION: Full Name: Name of Landlord, Property Owner, Bank, Etc.: Address: Address: City, State, Zip Code: City, State, Zip Code: HOUSING DISCRIMINATION BASIS I have been discriminated against because of my (check all that apply): Race Color Religion Sex Pregnancy Age National Origin Disability Familial Status Retaliation Did the discrimination include unwelcome and offensive harassment? Yes No Did the discrimination include sexual harassment? Yes No Date (month, day, and year) when the last incident of discrimination, harassment, or retaliation occurred: ____________ Full name and job title of each person involved in the discrimination, harassment, or retaliation: __________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________ I -

Read the Transcript

>> I just moved to a new city. I just moved to a new city. And finding a decent place to live was a real challenge. I mean, there are so many hoops to jump through. But just a couple of generations ago, there were even more barriers for someone who looks like me. I didn't see any "whites only" signs at the open house. When I went to sign the contract, the landlord didn't lie to me and tell me the apartment was already rented to someone else. Before President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fair Housing Bill in 1968, that kind of craziness was totally legal. Landlords could refuse to sell or rent housing because of someone's race, color, religion, sex, family status, national origin, or pretty much any reason. But the Fair Housing Act changed all of that, right? It eliminated housing discrimination, fostered integration, pretty much solved all of our problems. Eh, not so much. So what does that mean for us? What is the impact of housing discrimination today? Let's take a step back. Near the end of the Civil War, General William T. Sherman wanted to set aside land for formerly enslaved families so they weren't starting from scratch. The rallying cry was "40 acres and a mule." But it never happened. Lincoln was assassinated. And Sherman's order was revoked. In spite of this, black communities started to advance. There were black newspapers, black-owned businesses, even black senators within a decade of the end of the Civil War. -

Housing-Related Hate Activity

Housing-Related Hate Activity National Fair Housing Alliance Agenda • Fair Housing Act’s prohibition against housing-related hate activity • Responding to housing-related hate activity – Forming a response network – Rapid response protocols Fair Housing Act • Title VIII of Civil Rights Act of 1968 • Prohibits discrimination in housing-related transactions because of: –Race – Color – Religion – National origin –Sex – Disability – Familial status (children under age 18 in household) Housing Discrimination • Any attempt to prohibit or limit free and fair housing choice because of a protected class • Applies to all housing-related transactions – Rentals – Real estate sales – Mortgage lending – Appraisals – Homeowners insurance – Zoning Housing-Related Hate Activity • Unlawful to coerce, intimidate, threaten, or interfere with any person in the exercise or enjoyment of fair housing rights, such as: – Renting or buying a house – Reasonable accommodations/modifications – Filing a fair housing complaint • Unlawful to retaliate against someone for exercising fair housing rights – Or for helping another person exercise fair housing rights • 42 U.S.C. § 3617 HUD Regulation • 24 C.F.R. § 100.400 • Unlawful to: – Threaten, intimidate, or interfere with persons in their enjoyment of a dwelling because of their protected class or the protected class of visitors/associates – Intimidate or threaten any person because that person is engaging in activities designed to make other persons aware of, or encouraging such other persons to exercise, fair housing -

Housing Discrimination Against Victims of Domestic Violence

Housing Discrimination Against Victims of Domestic Violence By Wendy R. Weiser and Geoff Boehm In their government-subsidized two-bed- The notice referred to the August 2 incident room apartment on the morning of August in which Ms. Alvera was injured.1 2, 1999, Tiffanie Ann Alvera’s husband Ms. Alvera’s story is not an aberra- physically assaulted her. The police arrest- tion. Women across the country are ed him, placed him in jail, and charged denied housing opportunities or evicted him with assault. He was eventually con- from their housing simply because they victed. That same day, after receiving med- are victims of domestic violence.2 Land- ical treatment for the injuries her husband lords who deny housing to victims of inflicted, Ms. Alvera went to Clatsop domestic violence not only heap further County Circuit Court and obtained a punishment on innocent victims but also restraining order prohibiting him from help cement the cycle of violence. By coming near her or into the apartment forcing victims to make the terrible choice complex where they lived. When she gave between suffering in silence and losing the resident manager of the apartment their housing, those landlords effectively complex a copy of the restraining order, discourage victims from reporting their she was told that the management com- abuse or otherwise taking steps to pro- pany had decided to evict her as a result tect themselves. Those victims who do of the incident of domestic violence. Two undertake to protect themselves find it days later Ms. Alvera’s landlord served her much more difficult to achieve indepen- with a twenty-four-hour notice terminat- dence from their abusers when they are ing her tenancy. -

Understanding the Fair Housing

THE FAIR HOUSING ACT: HOUSING RELATED HATE ACTS VANESSA A. BULLOCK, ESQ. [email protected] 731-426-1332 Disclaimer The work that provided the basis for this presentation was supported by funding under a grant with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The substance and findings of the work are dedicated to the public. The author and presenter are solely responsible for the accuracy of the statements and interpretations contained in this presentation. Such interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Government. THE FAIR HOUSING ACT Protected Classes The Fair Housing Act prohibits discrimination in housing- related transactions because of: ▪ Race ▪ Color ▪ Religion ▪ National Origin ▪ Sex (including gender identity and sexual orientation) ▪ Familial Status (children under the age of 18 in household) ▪ Disability Status The Fair Housing Act: Covered Markets Rental Sales Lending Insurance Zoning Advertisements All other areas connected with residential housing The Fair Housing Act: Covered Dwellings Private and Subsidized Units Single Family Homes Multi-Family Units Shelters Group Homes Assisted Living College Dormitories All Other Residential Housing: “Where I live” The Fair Housing Act: Covered Entities Owners Managers/Management Companies Homeowner’s Associations/Condo Boards Lenders Real Estate Agents Governments Insurers All persons/entities involved with residential housing Prohibited Activities ▪ Refusing to sell or rent after the making of a bona fide offer, or otherwise making unavailable -

Removing Housing Barriers to Women's Workforce Participation

Removing Housing Barriers to Women’s Workforce Participation YWCA believes that safe, decent, affordable housing is vital for women’s successful participation in the workforce. Housing stability supports women’s ability to find and retain employment, attend education classes, and participate in job training programs. Moreover, securing affordable housing enhances women’s economic security because more resources are available for child care, health care, education, nutrition, and other necessities. Access to safe and affordable housing also plays a critical role in empowering survivors of domestic violence to recover from their experiences with violence.i Despite the critical role that housing plays in women’s workforce participation and overall economic stability, high costs, affordable housing shortages, discrimination, and other factors place safe, decent, affordable housing out of reach for many women – particularly women of color, lower income women, working mothers, and survivors of domestic violence. This briefing paper explores the connections between housing and employment; factors that reduce access to safe, quality housing for lower income households; and policy solutions that would address housing barriers to successful workplace participation for women, particularly women of color. Since 1858, YWCA housing programs have provided women with a firm foundation to further their educations and to more fully participate in the workforce. YWCA currently provides housing and specialized services for more than 35,000 women and family -

Errata Sheet Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice February 11

Errata Sheet Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice February 11, 2020 Marin County Board of Supervisors The following changes will be made to the 2020 Marin County of Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice, subject to the approval of the Marin County Board of Supervisors: 1. Page 28 – Marin Transit Authority should be changed to Marin Transit 2017 data on ridership should be as follows: 29% of riders were White; 52% were Latinx; 7% were African American; 5% were Asian and 7% were other. 2. Page 37, Paragraph 4 should read: In the 2017-2018 school year, 127 students were enrolled in Bayside MLK of which 3.9% were White, 27.6% were Latinx, 7.1% were Asian, 9.4% identified as two or more races and 50.4% were African American 3. Page 55, Section 5.3, Changes in Homeownership, Second sentence should read: In 2017, 64.2% of Marin households owned their homes County of Marin Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice February 2020 Prepared by the Marin County Community Development Agency 0 Table of Contents Executive Summary 4 1 Introduction and General Summary of the Analysis 7 1.1 Purpose of the Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing 7 1.2 Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing 7 1.3 Definition of Impediments 8 1.4 Protected Classes 8 1.4.1 Race and Ethnicity 8 1.5 Methodology and Data Collection 9 2 Jurisdictional Background Information 12 2.1 County Demographics 12 2.2 Consolidated Metropolitan Statistical Area 12 2.3 Geography 12 2.4 Available Land for Development 12 2.5 Zoning Codes 13 2.6 Marin County -

San Diego History Center Is One of the Largest and Oldest Historical Organizations on the West Coast

The Journal of San Diego Volume 61 Spring 2015 Number 2 • The Journal of San Diego History Diego San of Journal 2 • The Number 2015 Spring 61 Volume History Publication of The Journal of San Diego History is underwritten by major grants from the Robert D. L. Gardiner Foundation and the Quest for Truth Foundation, established by the late James G. Scripps. Additional support is provided by “The Journal of San Diego History Fund” of the San Diego Foundation and private donors. Founded in 1928 as the San Diego Historical Society, today’s San Diego History Center is one of the largest and oldest historical organizations on the West Coast. It houses vast regionally significant collections of objects, photographs, documents, films, oral histories, historic clothing, paintings, and other works of art. The San Diego History Center operates two major facilities in national historic landmark districts: The Research Library and History Museum in Balboa Park and the Serra Museum in Presidio Park. The San Diego History Center presents dynamic changing exhibitions that tell the diverse stories of San Diego’s past, present, and future, and it provides educational programs for K-12 schoolchildren as well as adults and families. www.sandiegohistory.org Front Cover: Colorized postcards from the 1915 Panama-California Exhibition. (Clockwise) California Tower, Botanical Building, Cabrillo Bridge, and Commerce and Industries Building. Back Cover: USO Headquarters at Horton Plaza, World War II, supported by the Wax Family of San Diego. Design and Layout: Allen Wynar Printing: Crest Offset Printing Editorial Assistants: Travis Degheri Cynthia van Stralen Joey Seymour Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. -

State Government Oral History Program

California State Archives State Government Oral History Program Oral History Interview with PAUL J. LUNARDI California State Assemblyman, 1958 - 1963 California State Senator, 1963 - 1966 Legislative Representative, California Wine Institute, 1966 - 1988 March 10, 11, 24, 30, and April 7, 1989 Roseville and Sacramento, California By Donald B. Seney Oral History Program Center for California Studies California State University, Sacramento RESTRICTIONS ON THIS INTERVIEW None. LITERARY RIGHTS AND QUOTATION This manuscript is hereby made available for research purposes only. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the California State Archivist or Oral History Program, Center for California Studies, California State University, Sacramento. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to: California State Archives 1020 O Street, Room 130 Sacramento, CA 95814 or Oral History Program Center for California Studies California State University, Sacramento 6000 J Street Sacramento, CA 95819 The request should include identification of the specific passages and identification of the user. It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows: Paul J. Lunardi, Oral History Interview, Conducted 1989 by Donald B. Seney, Oral History Program, California State University, Sacramento, for the California State Archives State Government Oral History Program. Information (91(i) -145-4293 California Stale Archives March Fong Eu Dncunu'iil Restoration (9](i) 445-4293 1020 O Street, Room ISO Exliil)it Hall (916) 445-0748 Secretary of State Legislative Bill Service (910)445-2832 Sacramento, CA 95814 (prior )ears) PREFACE On September 25, 1985, Governor George Deukmejian signed into law A.B. -

Legislators of California

The Legislators of California March 2011 Compiled by Alexander C. Vassar Dedicated to Jane Vassar For everything With Special Thanks To: Shane Meyers, Webmaster of JoinCalifornia.com For a friendship, a website, and a decade of trouble-shooting. Senator Robert D. Dutton, Senate Minority Leader Greg Maw, Senate Republican Policy Director For providing gainful employment that I enjoy. Gregory P. Schmidt, Secretary of the Senate Bernadette McNulty, Chief Assistant Secretary of the Senate Holly Hummelt , Senate Amending Clerk Zach Twilla, Senate Reading Clerk For an orderly house and the lists that made this book possible. E. Dotson Wilson, Assembly Chief Clerk Brian S. Ebbert, Assembly Assistant Chief Clerk Timothy Morland, Assembly Reading Clerk For excellent ideas, intriguing questions, and guidance. Jessica Billingsley, Senate Republican Floor Manager For extraordinary patience with research projects that never end. Richard Paul, Senate Republican Policy Consultant For hospitality and good friendship. Wade Teasdale, Senate Republican Policy Consultant For understanding the importance of Bradley and Dilworth. A Note from the Author An important thing to keep in mind as you read this book is that there is information missing. In the first two decades that California’s legislature existed, we had more individuals serve as legislators than we have in the last 90 years.1 Add to the massive turnover the fact that no official biographies were kept during this time and that the state capitol moved seven times during those twenty years, and you have a recipe for missing information. As an example, we only know the birthplace for about 63% of the legislators. In spite of my best efforts, there are still hundreds of legislators about whom we know almost nothing. -

Legislatorfairemp00rumfrich.Pdf

All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the Regents of the University of California and William Byron Rumford , dated October 31, 1972. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. Requests for r>ermission to quote for publication should be addressed to the Regional Oral History Office, ^86 Library, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The legal agreement with William Byron Rumford requires that he be notified of the request and allowed, thirty days in which to respond. The Bancroft Library University of California/Berkeley Regional Oral History Office Earl Warren Oral History Project William Byron Rumford LEGISLATOR FOR PAIR EMPLOYMENT, PAIR HOUSING, AND PUBLIC HEALTH With an Introduction by A. Wayne Amerson An Interview Conducted by Joyce A. Henderson Amelia Fry Edward France Copy No v 1973 by The Regents of the University of California William Byron Rumford June, 1966 TABLE OP CONTENTS William Byron Rumford PREFACE i INTRODUCTION by A. Wayne Amerson ill INTERVIEW HISTORY x BIOGRAPHICAL SUMMARY xi I EARLY YEARS 1 Family Background 1 College Years 5 A Pharmacist at Highland Hospital 8 II BEGINNING PUBLIC SERVICE 13 The Rent Control Board 13 Venereal Disease Investigator 15 Emergency Housing Committee 17 The Berkeley Interracial Committee 18 The Appomattox Club 2b III EARLY YEARS IN THE CALIFORNIA ASSEMBLY 2? First Campaign and. -

William Byron Rumford Papers, 1934-1982

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/k6g15xsg No online items Finding Aid to the William Byron Rumford papers, 1934-1982 Mario H. Ramirez The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the William Byron BANC MSS 73/112 c 1 Rumford papers, 1934-1982 Finding Aid to the William Byron Rumford papers, 1934-1982 Collection number: BANC MSS 73/112 c The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Finding Aid Author(s): Mario H. Ramirez Date Completed: 2013 Finding Aid Encoded By: GenX © 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: William Byron Rumford papers Date (inclusive): 1934-1982 Collection Number: BANC MSS 73/112 c Creator: Rumford, William Byron Extent: 10 cartons, 1 box, 1 oversize box, 1 oversize folder (13.50 linear feet) Repository: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: The William Byron Rumford papers including correspondence, subject files, legislative files and campaign materials. Languages Represented: Collection materials are in English Physical Location: Many of the Bancroft Library collections are stored offsite and advance notice may be required for use.