Postcards from the Edge David Chandler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anne Karpf/The Sound of Home? Some Thoughts on How the Radio Voice Anchors, Contains and Sometimes Pierces (Pre-Print Version; Published in The

1 Anne Karpf/The sound of home? Some thoughts on how the radio voice anchors, contains and sometimes pierces (pre-print version; published in The Radio Journal, vol.11, no.1, April 2013, pp.59-73) Abstract This article argues that while psychoanalytic theory has been valuably employed by television, film and cultural studies, there has been no comparable 'psychoanalytic turn' in radio studies. It suggests that the concept of 'containment', as developed variously by Wilfred Bion and Esther Bick, might go some way to explain the powerful role that the voice of the radio presenter can play in the regular listener's internal world, with the capacity both to 'hold' the listener together, and to transform overwhelming fears into more manageable feelings. It argues that the disembodied radio voice does this partly because it recalls the prenatal power of the maternal voice, and partly through the temporal order that regular radio voices impose on the internal and external world. Both Second World War British radio catchphrases and Roosevelt's Fireside Chats are discussed in relation to their containment function. The article also explores the radio as a transitional space, as defined by Donald Winnicott, through which it can constitute listeners into an 'imagined community'. It ends by reflecting on the impact of the angry voice of 2 the 'shock-jock' which, it suggests, amplifies rather than contains overwhelming feelings.1 Contributor's details Anne Karpf is Reader in Professional Writing and Cultural Inquiry at London Metropolitan University. A journalist, broadcaster and radio critic of The Guardian for seven years, her books include 'The Human Voice' (Bloomsbury, 2006; Ehrenwirth, 2007; Autrement, 2008; Soshisha, 2008). -

Simonelli on Hendy, 'Life on Air: a History of Radio Four'

H-Albion Simonelli on Hendy, 'Life on Air: A History of Radio Four' Review published on Friday, January 28, 2011 David Hendy. Life on Air: A History of Radio Four. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. Illustrations. ix + 518 pp. $55.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-19-924881-0. Reviewed by David Simonelli (Youngstown State University) Published on H-Albion (January, 2011) Commissioned by Thomas Hajkowski David Hendy’s introduction opens with a pair of extreme vignettes that aptly capture the nature of the Radio Four audience. In May 1988, an elderly woman strode into Broadcasting House and opened fire with a pistol full of blanks when she could not receive Radio Four in Blackpool; more tragically, a vicar in Surrey beat his wife to death with his radio when he objected to someone’s musical tastes as broadcast on the program Desert Island Discs. As a loyal National Public Radio (NPR) listener, one sniffs at the idea that NPR could elicit the same response, no matter how demented the listener might be. To my knowledge, there is no true equivalent in any other Western nation-state’s culture to match the role that Radio Four plays in Britain. The founder of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), Sir John Reith, declared that the entire service had a mission “to inform, to educate, and to entertain” (p. 400). In post-Victorian terms, Reith’s idea was to improve people through listening and get them to like the effort. While other branches of BBC radio and television have drifted off to serve each single aspect of that mandate, only Radio Four has kept a true balance between information, education, and entertainment. -

Radio 4 Listings for 21 – 27 August 2021 Page 1 of 16 SATURDAY 21 AUGUST 2021 SAT 06:07 Open Country (M000ytzz) Jay Rayner Hosts the Culinary Panel Show

Radio 4 Listings for 21 – 27 August 2021 Page 1 of 16 SATURDAY 21 AUGUST 2021 SAT 06:07 Open Country (m000ytzz) Jay Rayner hosts the culinary panel show. Sophie Wright, Tim A Fabric Landscape Anderson, Asma Khan and Dr Annie Gray share delectable SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000yvbc) ideas and answer questions from the audience. The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. Fashion designer and judge of The Great British Sewing Bee, Patrick Grant, has a dream: he wants to create a line of jeans This week, the panellists tell us their favourite recipes for that made in Blackburn. It sounds simple, but Patrick wants to go classic savoury nibble, the cheese straw. They also delve into SAT 00:30 Hello, Stranger by Will Buckingham (m000yvbf) the whole hog - growing the crop to make the fabric in the world of fresh peas and, when it comes to cooking with this Episode 5 Blackburn, growing the woad to dye it blue in Blackburn and small green vegetable, our panellists are not quite peas in a pod! finally processing the flax into linen and sewing it all When Will Buckingham's partner died, he coped with his grief together...in Blackburn. Nigerian food writer Yemisi Aribisala explains the significance by throwing his doors open to new people, and travelling alone of soup in Nigerian cuisine, and tells us what goes into the to far-flung places among strangers. 'Strangers are unentangled In this programme, the writer and broadcaster Ian Marchant perfect jollof rice. in our worlds and lives,' he writes, 'and this lack can lighten our travels to a tiny field of flax on the side of the Leeds and own burdens.' Starting from that experience of personal grief, Liverpool Canal, where Patrick and a group of passionate local Producer: Hannah Newton he draws on his knowledge as a philosopher and anthropologist, people are trying to make this dream a reality, and bring the Assistant Producer: Aniya Das as well as a keen and wide-roaming traveller, to explore the textile industry back to Blackburn. -

Shipping Forecast Task Sheet V2

Royal Meteorological Society Shipping Forecast Workshop Marine Forecast Glossary Marine forecasts contain a number of terms which are used to convey specific meanings. Gale warnings Gale Winds of at least Beaufort force 8 (34–40 knots) or gusts reaching 43–51 knots Severe gale Winds of force 9 (41–47 knots) or gusts reaching 52–60 knots Storm Winds of force 10 (48–55 knots) or gusts reaching 61–68 knots Violent storm Winds of force 11 (56–63 knots) or gusts of 69 knots or more Hurricane force Winds of force 12 (64 knots or more) Note: The term used is ‘hurricane force’; the term ‘hurricane’ on its own means a true tropical cyclone, not experienced in British waters. Imminent Expected within six hours of time of issue Soon Expected within six to 12 hours of time of issue Later Expected more than 12 hours from time of issue Visibility Very poor Visibility less than 1,000 metres Poor Visibility between 1,000 metres and 2 nautical miles Moderate Visibility between 2 and 5 nautical miles Good Visibility more than 5 nautical miles Movement of pressure systems Slowly Moving at less than 15 knots Steadily Moving at 15 to 25 knots Rather quickly Moving at 25 to 35 knots Rapidly Moving at 35 to 45 knots Very rapidly Moving at more than 45 knots PAGE 1 Pressure tendency in station reports Rising (or falling) more slowly Pressure rising (or falling) at a progressively slower rate through the preceding three hours Rising (or falling) slowly Pressure change of 0.1 to 1.5 hPa in the preceding three hours Rising (or falling) Pressure change of 1.6 to 3.5 hPa in the preceding three hours Rising (or falling) quickly Pressure change of 3.6 to 6.0 hPa in the preceding three hours Rising (or falling) v. -

Saturday, July 7, 2018 | 15 | WATCH Monday, July 9

6$785'$<-8/< 7+,6,6123,&1,& _ )22' ,16,'( 7+,6 :((. 6+233,1* :,1(6 1$',<$ %5($.6 &KHFNRXW WKH EHVW LQ ERWWOH 683(50$5.(7 %(67 %8<6 *UDE WKH ODWHVW GHDOV 75,(' $1' 7(67(' $// 7+( 58/(6 :H FKHFN RXW WRS WUDYHO 1$',<$ +XVVDLQ LV D KDLUGU\HUV WR ORRN ZDQWDQGWKDW©VZK\,IHHOVR \RXGRQ©WHDWZKDW\RX©UHJLYHQ WRWDO UXOHEUHDNHU OXFN\§ WKHQ \RX JR WR EHG KXQJU\§ JRRG RQ WKH PRYH WKHVH GD\V ¦,©P D 6KH©V ZRQ 7KLV UHFLSH FROOHFWLRQ DOVR VHHV /XFNLO\ VKH DQG KXVEDQG $EGDO SDUW RI WZR YHU\ %DNH 2II SXW KHU IOLS D EDNHG FKHHVHFDNH KDYH PDQDJHG WR SURGXFH RXW D VOHZ RI XSVLGH GRZQ PDNH D VLQJOH FKLOGUHQ WKDW DUHQ©W IXVV\HDWHUV GLIIHUHQW ZRUOGV ¤ ,©P %ULWLVK HFODLU LQWR D FRORVVDO FDNH\UROO VR PXFK VR WKDW WKH ZHHN EHIRUH 5(/$; DQG ,©P %DQJODGHVKL§ WKH FRRNERRNV DQG LV DOZD\V LQYHQW D ILVK ILQJHU ODVDJQH ZH FKDW VKH KDG DOO WKUHH *$0(6 $336 \HDUROG H[SODLQV ¦DQG UHDOO\ VZDS WKH SUDZQ LQ EHJJLQJ KHU WR GROH RXW IUDJUDQW &RQMXUH XS RQ WKH WHOO\ ¤ SUDZQ WRDVW IRU FKLFNHQ DQG ERZOIXOV RI ILVK KHDG FXUU\ EHFDXVH ,©P SDUW RI WKHVH 1DGL\D +XVVDLQ PDJLFDO DWPRVSKHUH WZR DPD]LQJ ZRUOGV , KDYH ¦VSLNH§ D GLVK RI PDFDURQL ¦7KH\ ZHUH DOO RYHU LW OLNH WHOOV (//$ FKHHVH ZLWK SLFFDOLOOL ¤ WKH ¨0XPP\ 3OHDVH FDQ ZH KDYH 086,& QR UXOHV DQG QR UHVWULFWLRQV§ :$/.(5 WKDW 5(/($6(6 ZRPDQ©V D PDYHULFN WKDW ULJKW QRZ"© , ZDV OLNH ¨1R +HQFH ZK\ WKUHH \HDUV RQ IURP IRRG LV PHDQW +RZHYHU KHU DSSURDFK WR WKDW©V WRPRUURZ©V GLQQHU ,©YH :H OLVWHQ WR WKH ZLQQLQJ *UHDW %ULWLVK %DNH 2II WR EH IXQ FODVKLQJDQG PL[LQJ IODYRXUVDQG MXVW FRRNHG LW HDUO\ \RX©YH JRW ODWHVW DOEXPV WKH /XWRQERUQ -

0 Baftelle Pacific Northwest Laboratories

JI PNWD-2129 HEDR uc-000 I Relative to Hanford Production Facilities Operations Originated on the Hanford I. .- Siie Between 1961 and 1972 REPOSITORY vu .L April 1993 I MIA .u\ Prepared for the Texhnical Steering Panel and the Centers for Disease Control under Contract 200-92-0503(CDC)/18620(BNW) 0 Baftelle Pacific Northwest Laboratories I123411 This rrport was pmpared by Battelle as an account of sponsored -arch .- activities. Ncitber Sponsor nor Banelle nor any person aaing on behalf of eitha: .I ............. _-.. _.-.-.-I --. ...... MAKES ANY WARRANTY OR RWIESPCTATION; EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, with rspeato thc accuncy, completeness, or useiulness ofthe information , .. -_. ...... *%... - ......... contained in this repoh or that the use of any information, apparatus, proces, or composition disclosed in this repon may not infringe privately . - -_ ".*I - .,, ~. .- . I., -.. , , - own&d~nghO:or .- _-.- ........ ...--.-.e -any liabilities 4th rr~pcctto the use'of, or damages multing fr~n the use ob, any infomution, m,pmcess, or composition diddin this rrpoh Rhceherein to any specific commercial produu process. or miceby trade name. tmianak manufacrum, or othcrwiset:does not necessarily connitua or imply endorsemcm. mommendation, or favoring by Sponsor or Bandlc List of Currently Classified Documents Relative to Hanford Production Facilities Operatiom Originated on the Hantord Site Beween 1961-1 972 PREFACE The United States Department of Energy (DOE) hat declared that all Hanfordplutonium production- urd opefatione related infomation genere~tedbetween 1944 and 1972 is declassified. Any documents found and deemed useful lor meeting Hanford Environmental Dose Reconstruction (HEDR) objectives may be declatsifiec with or withoul deletions in accordance with DOE guidance by Authorized Derivative Declusifiem. -

Radio 4 Listings for 1 – 7 March 2008 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 01 MARCH 2008 Museum in Bristol

Radio 4 Listings for 1 – 7 March 2008 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 01 MARCH 2008 museum in Bristol. It is the winner of numerous awards and the SAT 17:30 The Bottom Line (b0091tmm) Dockyard Museum charts the history of Brunel's masterpiece. Evan Davis presents the business magazine. Entrepreneurs and SAT 00:00 News and Weather (b0091tlt) business leaders talk about the issues that matter to their The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4, John is joined by Matthew Tanner, Nancy Chambers and companies and their customers. followed by weather. Captain Chris Young from the ss Great Britain Trust; Cruise ship captain Alistair McLundie; Martyn Heighton, Head of National Historic Ships and Alec Lewis, Director of fundraising SAT 17:54 Shipping Forecast (b0091tmn) SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b0090m35) for the Waverley Steam Navigation Company; to hear how this The latest shipping forecast. Sacre Cordon Bleu: What the French Know About Cooking first ever luxury ocean liner transformed the way people travelled, as its speed enabled the development of tourism by Episode 5 sea. SAT 17:57 Weather (b0091tmp) The latest weather forecast. Sacre Cordon Bleu: Alex Lowe reads from Michael Booth's John discovers that although modern passenger sea travel is account of his French culinary education. 5/5: Michael faces the flourishing it is almost entirely in the leisure market, whether Superior Cuisine exam, his toughest test yet. for cruises or day trips. SAT 18:00 Six O'Clock News (b0091tmq) The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4, followed by Weather. -

Understanding the Shipping and Inshore Waters Forecasts

UNDERSTANDING THE SHIPPING AND INSHORE WATERS FORECASTS The Shipping Forecast and Inshore Waters Forecast both use a standard and abbreviated format to pass a lot of information in a short period of time - by knowing what's being said and in what order (always the same) it's possible to gain an understanding of the conditions, even in poor reception areas if listening to the forecast on marine VHF. The terms used are standardised. The Coastguard broadcasts Marine Safety Information (MSI) on marine VHF. As well as marine VHF, weather bulletins for shipping are broadcast daily on BBC Radio 4. The bulletins consist of a gale warning summary, general synopsis, sea-area forecasts and coastal station reports. In addition, gale warnings are broadcast at the first available programme break after receipt. If this does not coincide with a news bulletin, the warning will be repeated after the next news bulletin. Shipping Area Forecast Example Shipping Area Forecast - this is Explanation (See also "Terms used") what you'll actually hear during a radio transmission, or read on a text forecast. THE SHIPPING FORECAST ISSUED BY THE MET Time & date of the forecast. OFFICE, ON BEHALF OF THE MARITIME AND COASTGUARD AGENCY, AT 1725 ON SATURDAY 02 JULY 2005 THERE ARE WARNINGS OF GALES IN SHANNON Any Gale Warnings are issued first, with details ROCKALL MALIN HEBRIDES BAILEY FAIR ISLE of the Sea Areas to which they apply. See the FAEROES AND SOUTHEAST ICELAND Sea Areas chart below. THE GENERAL SYNOPSIS AT 1300 This is a general overview - at 1300 there is a LOW JUST WEST OF ROCKALL 987 EXPECTED low pressure area to the west of Rockall - with a BAILEY 983 BY 1300 TOMORROW barometric pressure of 987. -

Battery Driven/ J I Any Two-Valve Set Becomes at Once a Fine Loud-Speaker 1

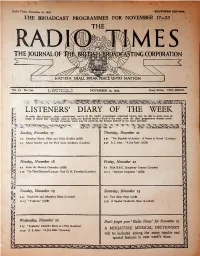

1 ” — ■ f • • * '• . A » Iludio Times, November 15, 1020. • SOUTHERN EDITION. / r‘ THE BROADCAST PROGRAMMES FOR NOVEMBER 17-23 2S ‘ 1 THE ! I IM E S THE JOURNAL OF Tm BRI®SH2BR0ftD©WTING CORPORATION • < m 2 NATION SHALL SPEAKTEACE UNTO NATION f Registered nt tl»c 1 Vol. 25. No. 320. LG.P.O. as a Ncwspnper.J NOVEMBER 15, 1929. Every Friday. TWO PENCE. i 1 LISTENERS’ DIARY OF THE WEEK I < In order that listeners, after a preliminary survey of the week’s programmes contained herein, may be able to make notes of items to which thev specially want to listen, we publish below a diary of the week, with the chief programmes already noted- further favourite items may be noted by the listener himself in the space provided. Sunday, November 17 Thursday, November 21 9.0 Chamber Music: Hans and Frida Kindler (5GB) 9.35 * The Republic of Austria : A Poster in Sound ' (London) I 1 9.5 Albert Sandler and the Park Lane Orchestra (London) 9.40 A. J. Alan : * A Joy Ride ’ (5GB) <1 I 1 < Monday, November 18 Friday, November 22 :> 2 9.0 From the Musical Comedies (5GB) S.o Fifth B.B.C. Symphony Concert (London) A 4 9.20 The Third National Lecture • Prof. G. M. Trevelyan (London) 10.15 f Intimate Snapshots ’ (5GB) ij < Tuesday, November 19 Saturday, November 23 * 9.40 Vaudeville and Alhambra Relay (London) 8.0 Two Short Plays (5GB) s 10.15 ‘ Typhoon ’ (5GB) 9.35 A Special Vaudeville Show (London) &s t < Wednesday, November 20 Don't forget your ‘ Radio Times' for November 22 S.15 * Typhoon,’ Conrad’s Story as a Play (London) < A MINIATURE MUSICAL DICTIONARY f: 10.40 A. -

The Story of the Shipping Forecast, from the Man Who Read It Page 10

The newspaper for BBC pensioners - with highlights from Ariel For those in peril on the sea The story of the Shipping Forecast, from the man who read it Page 10 July 2011 • Issue 5 original Harryhausen 40 years of models on 30 years of the local radio display Space Shuttle remembered Page 2 Page 5 Page 6 NEWS • LifE aftEr auNtiE • CLaSSifiEdS • Your LEttErS • obituariES • CroSPEro 02 GENEraL NEWS Ray Harryhausen’s iconic animation models and artwork at the National Media Museum Phil Oates, Acting Senior Press Officer at the National Media Museum in Bradford, writes about an interesting new exhibition in Bradford. Ray Harryhausen, and have been on show in Bradford since May 19. They will be displayed alongside examples of Harryhausen’s artwork for the films. Further objects from the Ray Harryhausen Collection will be exhibited at later dates as part of an ongoing rolling programme. The display is one of the first steps following last year’s agreement with The Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation to deposit the animator’s complete collection with the National Media Museum, which was announced during Harryhausen’s 90th birthday celebrations. Ray Harryhausen commented, ‘Knowing that my Collection is going to be cared for by the Museum, and that my Foundation will continue to be directly involved, is a great comfort and an acknowledgement that my work and art will be preserved for new Jason fights the skeletons, key drawing, Jason and the Argonauts (1963), © Ray Harryhausen. Courtesy of the Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation film makers to study and hopefully continue to appreciate.’ Some of the most famous models from Michael Harvey, the Museum’s Curator Centre of Excellence It aims to be the best museum in the the history of fantasy cinema are on of Cinematography, said, ‘To have agreed ‘This is perhaps one of the most important world for inspiring people to learn about, display at the National Media Museum with Ray and the Foundation to bring this cinematic collections in the world, says Tony engage with and create media. -

Chapter 3 Poetics of the Shipping Forecast

chapter 3 Poetics of the Shipping Forecast Sanna Nyqvist Abstract This essay investigates the intertextual manifestations of radio shipping forecasts in fiction, poetry and non- fiction from the United Kingdom, Ireland, Sweden and Finland. The literary adaptations and appropriations of the functional meteor- ological report often retain its peculiar melodic character that results from the compressed, elliptic listing of observations or warnings. In the listening experience evoked by many authors the relative safety of the radio listener’s everyday surround- ings contrasts with the threat of gales and harsh conditions for seafarers. A compar- ative analysis shows that despite the insularity of the shipping forecast as a cultural phenomenon, the “literature of the shipping forecast” is surprisingly similar in dif- ferent countries, exploring the same themes of nostalgia, loss of signification and definition of borders. The essay also investigates how the shipping forecast inevitably evokes questions of territorial conquest and exclusion of others, and how its literary adaptations tend to bracket the natural phenomena that are the very raison d’être of the shipping forecast. The shipping forecast is a curious radio broadcast. Issuing gale warnings for seafarers and communicating weather information from coastal stations, it is reminiscent of a time when reliable and up- to- date weather reports were avail- able only through radio. Nowadays, professional mariners as well as pleasure boaters get the necessary weather information through modern wireless tech- nologies, and the shipping forecast has become a relic in the radio’s programme schedule. Most of the avid listeners to the radio’s shipping forecast do not need the information it conveys: they are safely situated inland, far away from the rough seas and gushing winds. -

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 January 2021 Page 1 of 16

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 January 2021 Page 1 of 16 SATURDAY 02 JANUARY 2021 inspired by the teacher’s claims, they gave up friends, family SAT 07:00 Today (m000qxc6) and lucrative jobs - and it had all been worth it! They saw the Including Sports Desk, Weather and Thought for the Day. SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000qnkq) sick healed, the hungry fed and the dead raised to life. But just The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. when everything was going so well, Jesus was brutally murdered on trumped-up charges. When life throws you a curve ball, you SAT 09:00 Saturday Live (m000qxc8) begin to imagine them appearing from all directions. The Extraordinary stories, unusual people and a sideways look at the SAT 00:15 In Their Element (m000cn05) disciples did what we might be tempted to do too: stay at home world. Series 4 with your fears and lock the door. Strontium There are not enough bolts in the world that can stop God from SAT 10:30 The Kitchen Cabinet (m000qxcb) entering a room. Jesus had made his way past death, Series 30 Strontium is the 15th most common element in the earth yet we gravestones, and armed guards to get to his beleaguered really only come into contact with it in fireworks. It gives us the disciples, greeting them finally with one word: “Shalom” - Home Economics: Episode 21 deep red colour we admire in a pyrotechnics display. Andrea peace. This peace quelled their anxieties and soon the bunch of Sella, Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at UCL, meets Mike scared young people had turned into fearless world-changers.