5 Indeterminate Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Statically Indeterminate Trusses for Progressive Collapse

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses 2017 Analysis of Statically Indeterminate Trusses for Progressive Collapse Using Graphic Statics and Complexity Metrics Maximilian Edward Ororbia Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Recommended Citation Ororbia, Maximilian Edward, "Analysis of Statically Indeterminate Trusses for Progressive Collapse Using Graphic Statics and Complexity Metrics" (2017). Honors Theses. 412. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/412 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor Professor Stephen G. Buonopane for being an incredible mentor, an amazing teacher, and for providing me the opportunity to work on this research. Without his assistance and dedicated support, this thesis would not have been possible. I would also like to thank Professor Ronald D. Ziemian, who co-advised my honors thesis, and my committee member, Professor Dabrina Dutcher, for their valuable feedback, support, and guidance. Many thanks go to Professor Jeffrey C. Evans and Professor Kelly Salyards for encouraging and inspiring me to pursue research. I would also like to express my gratitude to the civil engineering faculty and staff at Bucknell University for facilitating an excellent education and outstanding research opportunities. Most importantly, none of this could have happened without my family. I am grateful for my mom and dad standing by my side and providing me with an infinite amount of love and support. -

Structural Analysis

Module 1 Energy Methods in Structural Analysis Version 2 CE IIT, Kharagpur Lesson 1 General Introduction Version 2 CE IIT, Kharagpur Instructional Objectives After reading this chapter the student will be able to 1. Differentiate between various structural forms such as beams, plane truss, space truss, plane frame, space frame, arches, cables, plates and shells. 2. State and use conditions of static equilibrium. 3. Calculate the degree of static and kinematic indeterminacy of a given structure such as beams, truss and frames. 4. Differentiate between stable and unstable structure. 5. Define flexibility and stiffness coefficients. 6. Write force-displacement relations for simple structure. 1.1 Introduction Structural analysis and design is a very old art and is known to human beings since early civilizations. The Pyramids constructed by Egyptians around 2000 B.C. stands today as the testimony to the skills of master builders of that civilization. Many early civilizations produced great builders, skilled craftsmen who constructed magnificent buildings such as the Parthenon at Athens (2500 years old), the great Stupa at Sanchi (2000 years old), Taj Mahal (350 years old), Eiffel Tower (120 years old) and many more buildings around the world. These monuments tell us about the great feats accomplished by these craftsmen in analysis, design and construction of large structures. Today we see around us countless houses, bridges, fly-overs, high-rise buildings and spacious shopping malls. Planning, analysis and construction of these buildings is a science by itself. The main purpose of any structure is to support the loads coming on it by properly transferring them to the foundation. -

Approximate Analysis of Statically Indeterminate Structures

Approximate Analysis of Statically Indeterminate Structures Every successful structure must be capable of reaching stable equilibrium under its applied loads, regardless of structural behavior. Exact analysis of indeterminate structures involves computation of deflections and solution of simultaneous equations. Thus, computer programs are typically used. 1 To eliminate the difficulties associated with exact analysis, preliminary designs of indeter- minate structures are often based on the results of approximate analysis. Approximate analysis is based on introducing deformation and/or force distribution assumptions into a statically indeterminate structure, equal in number to degree of indeter- minacy, which maintains stable equilibrium of the structure. 2 No assumptions inconsistent with stable equilibrium are admissible in any approximate analysis. Uses of approximate analysis include: (1) planning phase of projects, when several alternative designs of the structure are usually evaluated for relative economy; (2) estimating the various member sizes needed to initiate an exact analysis; 3 (3) check on exact analysis results; (4) upgrades for older structure designs initially based on approximate analysis; and (5) provide the engineer with a sense of how the forces distribute through the structure. 4 In order to determine the reac- tions and internal forces for indeterminate structures using approximate equilibrium me- thods, the equilibrium equations must be supplemented by enough equations of conditions or assumptions such that the resulting structure is stable and statically determinate. 5 The required number of such additional equations equals the degree of static indeter- minacy for the structure, with each assumption providing an independent relationship between the unknown reactions and/or internal forces. In approximate analysis, these additional equations are based on engineering judgment of appropriate simplifying assump- tions on the response of the structure. -

The Application of the Hardy Cross Method of Moment Distribution

AER-56-9 The Application of the Hardy Cross Method of Moment Distribution By H. A. WILLIAMS,1 STANFORD UNIVERSITY P. O., CALIF. This paper presents the basic principles of the Hardy criticisms and suggestions that he has given. Numerous features Cross method of analyzing continuous frames by dis of the paper have been instigated by him. tributing fixed-end moments and illustrates the appli cation of the method to various types of structures, in D e f i n i t i o n s cluding an elevator spar with supports on a line, the same In order to clarify the immediate discussion of the Hardy spar with deflected supports, and an airplane fuselage Cross method, the sign conventions and four terms will be de truss with loads between panel points. fined as follows: (1) Fixed-end moment is the moment which would exist at the OR years, structural engineers have ends of a loaded member if those ends were held rigidly against been searching for a simple method rotation. This is in accord with the ordinary usage for beams Fof determining stresses in statically ending in heavy walls.3 indeterminate structures. The Maxwell- (2) Unbalanced moment is numerically equal to the algebraic Mohr, least-work, and slope-deflection sum of all moments at a joint. The joint is balanced when the methods have been employed to a large sum of the moments equals zero. extent, but the laborious computations (3) Stiffness as herein used “is the moment at one end of a involved, together with the tendency for member (which is on unyielding supports at both ends) necessary small errors to accumulate, have dis to produce unit rotation of that end when the other end is fixed.” 4 couraged their use. -

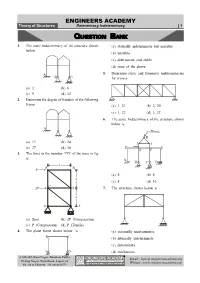

ENGINEERS ACADEMY Theory of Structures Determinacy Indeterminacy | 1

ENGINEERS ACADEMY Theory of Structures Determinacy Indeterminacy | 1 QUESTION BANK 1. The static indeterminacy of the structure shown (a) statically indeterminate but unstable below (b) unstable (c) determinate and stable (d) none of the above A 5. Determine static and kinematic indeterminacies B C for trusses (a) 3 (b) 6 (c) 9 (d) 12 2. Determine the degree of freedom of the following frame (a) 1, 21 (b) 2, 20 (c) 1, 22 (d) 2, 22 6. The static Indeterminacy of the structure shown below is. A Hinge K (a) 13 (b) 24 I J (c) 27 (d) 18 H G F E 3. The force in the member ‘CD’ of the truss in fig is A B C D a A B P (a) 4 (b) 6 a (c) 8 (d) 10 C 2P D 7. The structure shown below is a E F (a) Zero (b) 2P (Compression) (c) P (Compression) (d) P (Tensile) 4. The plane frame shown below is : (a) externally indeterminate B C (b) internally indeterminate (c) determinate A D (d) mechanism # 100-102, Ram Nagar, Bambala Puliya Email : info @ engineersacademy.org Pratap Nagar, Tonk Road, Jaipur-33 Website : www.engineersacademy.org Ph.: 0141-6540911, +91-8094441777 ENGINEERS ACADEMY 2 | Determinacy Indeterminacy Civil Engineering 8. The static Indeterminacy of the structure shown B D E F below is C G F hinge A C E H G D A B (a) 4 (b) 3 (c) 2 (d) 1 (a) unstable 12. The plane figure shown below is (b) stable, determinate th (c) stable, indeterminate to 5 degree B C (d) stable, indeterminate to 3rd degree 9. -

Chapter 16 / Analysis of Statically Indeterminate Structures

chap-16 17/1/2005 16: 29 page 467 Chapter 16 / Analysis of Statically Indeterminate Structures Statically indeterminate structures occur more frequently in practice than those that are statically determinate and are generally more economical in that they are stiffer and stronger. For example, a fixed beam carrying a concentrated load at mid-span has a central displacement that is one-quarter of that of a simply supported beam of the same span and carrying the same load, while the maximum bending moment is reduced by half. It follows that a smaller beam section would be required in the fixed beam case, resulting in savings in material. There are, however, disadvantages in the use of this type of beam for, as we saw in Section 13.6, the settling of a support in a fixed beam causes bending moments that are additional to those produced by the loads, a serious problem in areas prone to subsidence. Another disadvantage of statically indeterminate structures is that their analysis requires the calculation of displacements so that their cross-sectional dimensions are required at the outset. The design of such structures therefore becomes a matter of trial and error, whereas the forces in the members of a statically determinate structure are independent of member size. On the other hand, failure of, say, a member in a statically indeterminate frame would not necessarily be catastrophic since alternative load paths would be available, at least temporarily. However, the failure of a member in, say, a statically determinate truss would lead, almost certainly, to a rapid collapse. -

Teaching of Structural Analysis Into the Future

Civil Engineering Research in Ireland 2020 Teaching of Structural Analysis into the Future Dermot O’Dwyer, Department of Civil, Structural and Environmental Engineering, Museum Building, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The curricula of modern engineering programmes achieve a greater number of learning outcomes and cover a broader range of subject areas than ever before. This has resulted in a reduction in the hours that are available to teach structural engineering. At the same time the work of graduate structural engineers has changed and is likely to change further in the future. This paper considers what the kernel of essential knowledge for structural engineering should contain. More specifically it explores what elements of this kernel must be taught in university. The paper does not result in a definitive list of topics but makes some initial suggestions and promotes a rationale by which such a list might be arrived at. The paper argues that it is import to acknowledge that much of structural engineering analysis is pragmatic. Many of the basic theories are simplifications that are useful only in certain circumstances with certain materials. This complicates identifying a small set of structural engineering rules, Newton’s Laws excepted. While structural engineers should have knowledge of mechanics of solids, elasticity and methods of analysing statically indeterminate structures the level of complexity that needs to be achieved is not immediately clear. Modern structural engineering practice suggests that some areas of structural engineering analysis, such as the flexibility method, are obsolete; however, some of these methods are useful for exploring important concepts and developing qualitative analysis skills. -

Analysis of Statically Indeterminate Structures

CHAPTER 16 Analysis of Statically Indeterminate Structures Statically indeterminate structures occur more frequently in practice than those that are statically determinate and are generally more economical in that they are stiffer and stronger. For example, a fixed beam carrying a concentrated load at mid-span has a central displacement that is one quarter of that of a simply supported beam of the same span and carrying the same load, while the maximum bending moment is reduced by half. It follows that a smaller beam section would be required in the fixed beam case, resulting in savings in material. There are, however, disadvantages in the use of this type of beam for, as we saw in Section 13.7, the settling of a support in a fixed beam causes bending moments that are additional to those produced by the loads, a serious problem in areas prone to subsidence. Another disadvantage of statically indeterminate structures is that their analysis requires the calculation of displacements so that their cross-sectional dimensions are required at the outset. The design of such structures therefore becomes a matter of trial and error, whereas the forces in the members of a statically determinate structure are independent of member size. On the other hand, failure of, say, a member in a statically indeterminate frame would not necessarily be catastrophic since alternative load paths would be available, at least temporarily. However, the failure of a member in, say, a statically determinate truss would lead, almost certainly, to a rapid collapse. The choice between statically determinate and statically indeterminate structures depends to a large extent upon the purpose for which a particular structure is required. -

Euler-Bernoulli Beams

Professor Terje Haukaas The University of British Columbia, Vancouver terje.civil.ubc.ca Euler-Bernoulli Beams The Euler-Bernoulli beam theory was established around 1750 with contributions from Leonard Euler and Daniel Bernoulli. Bernoulli provided an expression for the strain energy in beam bending, from which Euler derived and solved the differential equation. That work built on earlier developments by Jacob Bernoulli. However, the beam problem had been addressed even earlier. Galileo attempted one formulation that aimed at determining the capacity of beams in bending, but misplaced the neutral axis. Earlier, Leonardo da Vinci also seems to have addressed the problem of beam bending. The two key assumptions in the Euler-Bernoulli beam theory are: • The material is linear elastic according to Hooke’s law • Plane sections remain plane and perpendicular to the neutral axis The latter is referred to as Navier’s hypothesis. In contrast, Timoshenko beam theory, which is covered in another document, relaxes the assumption that the sections remain perpendicular to the neutral axis, thus including shear deformation. In the following, the governing equations are established, followed by the formulation and solution of the differential equation. Thereafter, a section cross-section analysis describes the computation of stresses and cross-section constants. The starting point is 2D beam bending with the following sign conventions: § The z-axis is increases upwards § Displacement w is positive in the direction of the z-axis § Distributed load qz is positive in the direction of the z-axis § Bending moment that imposes tension at the bottom is positive § Clockwise shear force is positive § Counter-clockwise rotation q is positive, thus it can be interpreted as the slope of the deformed beam element § Tensile stresses and strains are positive, compression is negative Equilibrium The equilibrium equations are obtained by considering equilibrium in the x-direction for the infinitesimal beam element in Figure 1. -

Mala Babagana Gutti

A PRESENTATION ON STATICALLY INDETERMINATE STRUCTURES By Mala Babagana Gutti B.Eng. Student, Department of Civil and Water Resources Engineering, University of Maiduguri, Maiduguri, Nigeria Email: [email protected] January, 2017 CONTENTS • Introduction. • Structure. • Analysis. • Stable and Unstable Structures. • Support Types/Components. • Statically Determinate Structures. • External Determinacy. • Internal Determinacy. • Determinacy of Beams. • Statically Indeterminate Structures. • Externally Indeterminacy. • Internally Indeterminacy. • Difference Between Determinate and Indeterminate Structures. • Methods of Analyzing Indeterminate Structures. • Problems and Their Solutions Involving Indeterminate Structures. • References. Introduction Before beginning to analyze a structure, it is important to know what kind of structure it is. Different types of structures may need to be analyzed using different methods. For example, structures that are determinate may be completely analyzed using only static equilibrium, whereas indeterminate structures require the use of both static equilibrium and compatibility relationships to find the internal forces. In addition, real structures must be stable. This means that the structure can recover static equilibrium after a disturbance. There is no point analyzing a structure that is not stable. Any structure is designed for the stress resultants of bending moment, shear force, deflection, torsional stresses, and axial stresses. If these moments, shears and stresses are evaluated at various critical sections, then based on these, the proportioning can be done. Evaluation of these stresses, moments and forces and plotting them for that structural component is known as analysis. Determination of dimensions for these components of these stresses and proportioning is known as design. What is a structure? Structure is an assemblage of a number of components like slabs, beams, columns, walls, foundations and so on, which remains in equilibrium. -

Sign Conventions Applied and Reaction Force Sign Conventions

Sign Conventions Sign conventions are a standardized set of widely accepted rules that provide a consistent method of setting up, solving, and communicating solutions to engineering mechanics problems--statics, dynamics, and strength of materials problems. There are two types-static and deformation. Static sign conventions govern the directions of applied and reaction forces and moments, for example, upward or downward. Deformation sign conventions govern the directions of internal forces and moments that deform a body, for example, stretch, compress, twist or bend. For statically determinate structures, static sign conventions are used to determine external reactions. Both types are used to determine internal forces and moments. For statically indeterminate structures, both types are needed to find external reactions and internal forces and moments. Applied and Reaction Force Sign Conventions Are Static Sign Conventions Applied and reaction forces that are directed toward a positive axis are assigned positive signs. For example, referring to Figure 1, the signs of the components of the various forces are: 1. Force 1: F1x sign = +, F1y sign = +; 2. Force 2: F2x sign = +, F2y sign = -; 3. Force 3: F3x sign = -, F3y sign = -; 4. Force 4: F4x sign = -, F4y sign = + Figure 1. Note: In some ENGR 2140 worked examples, the + y direction is assumed to be in the direction of the applied force. To illustrate, in worked Ex1-5, the forces PA and PB are assumed to be in the + y-direction. In many beam analysis problems, the + y-direction is in the direction of the applied force. The correctness of the result is ok, but the orientation of the + y-axis is downward, not upward.