Applying the Correct Standard of Review for Rape-Shield Evidentiary Rulings Robert E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core Principles of the Legal Profession

CORE PRINCIPLES OF THE LEGAL PROFESSION Resolution ratified on Tuesday October 30, 2018, during the General Assembly in Porto Preamble The lawyer’s role is to counsel, conciliate, represent and defend. In a society founded on respect for the law and for justice, the lawyer advises the client on legal matters, examines the possibility and the appropriateness of finding amicable solutions or of choosing an alternative dispute resolution method, assists the client and represents the client in legal proceedings. The lawyer fulfils the lawyer’s engagement in the interest of the client while respecting the rights of the parties and the rules of the profession, and within the boundaries of the law. Over the years, each bar association has adopted its own rules of conduct, which take into account national or local traditions, procedures and laws. The lawyer should respect these rules, which, notwithstanding their details, are based on the same basic values set forth below. 1 - Independence of the lawyer and of the Bar In order to fulfil fully the lawyer’s role as the counsel and representative of the client, the lawyer must be independent and preserve his lawyer’s professional and intellectual independence with regard to the courts, public authorities, economic powers, professional colleagues and the client, as well as regarding the lawyer’s own interests. The lawyer’s independence is guaranteed by both the courts and the Bar, according to domestic or international rules. Except for instances where the law requires otherwise to ensure due process or to ensure the defense of persons of limited means, the client is free to choose the client’s lawyer and the lawyer is free to choose whether to accept a case. -

National Domestic Violence Prosecution Best Practices Guide Is a Living Document Highlighting Current Best Practices in the Prosecution of Domestic Violence

The National Domestic Violence Prosecution Best Practices Guide is a living document highlighting current best practices in the prosecution of domestic violence. It was inspired by the Women Prosecutors Section of the National District Attorneys Association (NDAA) and a National Symposium on the Prosecution of Domestic Violence Cases, hosted by the NDAA and Alliance for HOPE International in San Diego in October 2015. The two-day national symposium included 100 of our nation’s leading prosecutors re- envisioning the prosecution of domestic violence cases in the United States. Prosecutors and allied professionals are encouraged to continue developing this guide by contributing information on emerging best practices. NDAA recognizes that funding, local rules, or other state laws or local restrictions may prevent an office from adopting the various approaches suggested. This guide is not intended to replace practices and procedures already in operation, but to simply inform and recommend practices that are effective and consistent throughout the nation. For additional suggested edits to this document, contact [email protected], Chair, Domestic Violence Subcommittee, NDAA Women’s Section. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 4 Definitions ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Victim Recantation, Minimization, and -

The Competency Framework a Guide for IAEA Managers and Staff CONTENT

@ The Competency Framework A guide for IAEA managers and staff CONTENT INTRODUCTION. .3 1. CORE VALUES . .8 2. CORE COMPETENCIES . 10 COMMUNICATION . 11 TEAMWORK . 12 PLANNING AND ORGANIZING . 13 ACHIEVING RESULTS . 14 3. FUNCTIONAL COMPETENCIES. 15 LEADING AND SUPERVISING . 16 ANALYTICAL THINKING . 17 KNOWLEDGE SHARING AND LEARNING . 18 JUDGEMENT/DECISION MAKING . 19 TECHNICAL/SCIENTIFIC CREDIBILITY . 20 CHANGE MANAGEMENT . 21 COMMITMENT TO CONTINUOUS PROCESS IMPROVEMENT . 22 PARTNERSHIP BUILDING . 23 CLIENT ORIENTATION . 24 PERSUASION AND INFLUENCING . 25 RESILIENCE . 26 1 INTRODUCTION What is a competency framework? What are the components of the framework? A competency framework is a model that broadly describes The Agency’s competency framework includes core values, performance excellence within an organization. Such a and core and functional competencies. The defi nitions of framework usually includes a number of competencies these components are as follows: that are applied to multiple occupational roles within the organization. Each competency defi nes, in generic Core values are principles that infl uence people’s actions terms, excellence in working behaviour; this defi nition and the choices they make. They are ethical standards that then establishes the benchmark against which staff are are based on the standards of conduct for the international assessed. A competency framework is a means by which civil service and are to be upheld by all staff. organizations communicate which behaviours are required, valued, recognized and rewarded with respect to specifi c Core competencies provide the foundation of the occupational roles. It ensures that staff, in general, have a framework, describing behaviours to be displayed by all staff common understanding of the organization’s values and members. -

Job Profiles and Training for Employment Counsellors

The European Commission Mutual Learning Programme for Public Employment Services DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion JOB PROFILES AND TRAINING FOR EMPLOYMENT COUNSELLORS Analytical paper September 2012 This publication is commissioned by the European Community Programme for Employment and Social Solidarity (2007-2013). This programme is implemented by the European Commission. It was established to financially support the implementation of the objectives of the European Union in the employment, social affairs and equal opportunities area, and thereby contribute to the achievement of the EU2020 goals in these fields. The seven-year programme targets all stakeholders who can help shape the development of appropriate and effective employment and social legislation and policies, across the EU-27, EFTA-EEA and EU candidate and pre-candidate countries. For more information see: http://ec.europa.eu/progress For more information on the PES to PES Dialogue programme see: http://ec.europa.eu/social/pes-to-pes Editor: DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Unit C3 - Skills, Mobility and Employment Services. Author: dr Łukasz Sienkiewicz, Warsaw School of Economics In collaboration with ICF GHK and the Budapest Institute Please cite this publication as: European Commission (2012), Job profiles and training for employment counsellors, Brussels, Author: Łukasz Sienkiewicz The information contained in this publication does not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of the European Commission CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... i 1 INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................... 1 1.1 The skills and competences of employment counsellors have been identified as being critical to achieving successful placement outcomes, but little was known about existing profiles, training and career pathways from a comparative perspective .................................................................. -

The West Virginia Rules of Evidence

Revisions to the West Virginia Rules of Evidence Final Version The revisions are effective September 2, 2014. Approved by Order: June 2, 2014 Corrected by Orders: June 25, 2014 and August 28, 2014 The Court’s order and a PDF version of the proposed revisions are available online at: http://www.courtswv.gov/legal-community/court-rules.html West Virginia Rules of Evidence (Revised effective September 2, 2014) Table of Contents Article I. General Provisions Rule 611. Mode and Order of Examining Witnesses and Rule 101. Scope; Definitions 1 Presenting Evidence 20 Rule 102. Purpose 2 Rule 612. Writing Used to Refresh a Witness’s Rule 103. Rulings on Evidence 2 Memory 21 Rule 104. Preliminary Questions 3 Rule 613. Witness’s Prior Statement 22 Rule 105. Limiting Evidence That is not Admissible Rule 614. Court’s Calling or Examining a Witness 22 Against Other Parties or for Other Purposes 3 Rule 615. Excluding Witnesses 22 Rule 106. Remainder of or Related Writings or Recorded Statements 4 Article Vii. Opinion and Expert Testimony Article II. Judicial Notice Rule 701. Opinion Testimony by Lay Witnesses 23 Rule 201. Judicial Notice of Adjudicative Facts 4 Rule 702. Testimony by Expert Witnesses 23 Rule 202. Judicial Notice of Law 5 Rule 703. Bases of an Expert’s Opinion Testimony 24 Rule 704. Opinion on Ultimate Issue 24 Article III. Presumptions Rule 705. Disclosing the Facts or Data Underlying an Rule 301. Presumptions in Civil Cases Generally 5 Expert’s Opinion 24 Rule 706. Court Appointed Expert Witnesses 25 Article IV. Relevancy and its Limits Rule 401. -

Ohio Rules of Evidence

OHIO RULES OF EVIDENCE Article I GENERAL PROVISIONS Rule 101 Scope of rules: applicability; privileges; exceptions 102 Purpose and construction; supplementary principles 103 Rulings on evidence 104 Preliminary questions 105 Limited admissibility 106 Remainder of or related writings or recorded statements Article II JUDICIAL NOTICE 201 Judicial notice of adjudicative facts Article III PRESUMPTIONS 301 Presumptions in general in civil actions and proceedings 302 [Reserved] Article IV RELEVANCY AND ITS LIMITS 401 Definition of “relevant evidence” 402 Relevant evidence generally admissible; irrelevant evidence inadmissible 403 Exclusion of relevant evidence on grounds of prejudice, confusion, or undue delay 404 Character evidence not admissible to prove conduct; exceptions; other crimes 405 Methods of proving character 406 Habit; routine practice 407 Subsequent remedial measures 408 Compromise and offers to compromise 409 Payment of medical and similar expenses 410 Inadmissibility of pleas, offers of pleas, and related statements 411 Liability insurance Article V PRIVILEGES 501 General rule Article VI WITNESS 601 General rule of competency 602 Lack of personal knowledge 603 Oath or affirmation Rule 604 Interpreters 605 Competency of judge as witness 606 Competency of juror as witness 607 Impeachment 608 Evidence of character and conduct of witness 609 Impeachment by evidence of conviction of crime 610 Religious beliefs or opinions 611 Mode and order of interrogation and presentation 612 Writing used to refresh memory 613 Impeachment by self-contradiction -

THE CURRENT STATE of DNA EVIDENCE Christopher J

Capital Defense Journal Volume 4 | Issue 2 Article 7 Spring 4-1-1991 THE CURRENT STATE OF DNA EVIDENCE Christopher J. Lonsbury Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlucdj Part of the Criminal Procedure Commons, and the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Recommended Citation Christopher J. Lonsbury, THE CURRENT STATE OF DNA EVIDENCE, 4 Cap. Def. Dig. 11 (1992). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlucdj/vol4/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capital Defense Journal by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CapitalDefense Digest - Page 11 THE CURRENT STATE OF DNA EVIDENCE BY: CHRISTOPHER J. LONSBURY I. INTRODUCTION A General Description of DNA A new form of forensic testing harkens the day when science can Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) holds the chemically encoded say with near certainty whether a suspect was present at a crime scene. genetic information present in all living organisms. It exists in the Promising as this new technology is, a scientific method of itself cannot nucleus of every major type of cell except mature red blood cells. Each guarantee justice. Indeed, as presently received, the current identifica- DNA molecule is structured as a "double-helix," a long threadlike tion method carries with it the potential to impart a significant prejudicial molecule consisting of two threads that intertwine and coil. -

Expert Witnesses

Law 101: Legal Guide for the Forensic Expert This course is provided free of charge and is designed to give a comprehensive discussion of recommended practices for the forensic expert to follow when preparing for and testifying in court. Find this course live, online at: https://law101.training.nij.gov Updated: September 8, 2011 DNA I N I T I A T I V E www.DNA.gov About this Course This PDF file has been created from the free, self-paced online course “Law 101: Legal Guide for the Forensic Expert.” To take this course online, visit https://law101.training. nij.gov. If you already are registered for any course on DNA.gov, you may logon directly at http://law101.dna.gov. Questions? If you have any questions about this file or any of the courses or content on DNA.gov, visit us online at http://www.dna.gov/more/contactus/. Links in this File Most courses from DNA.Gov contain animations, videos, downloadable documents and/ or links to other userful Web sites. If you are using a printed, paper version of this course, you will not have access to those features. If you are viewing the course as a PDF file online, you may be able to use these features if you are connected to the Internet. Animations, Audio and Video. Throughout this course, there may be links to animation, audio or video files. To listen to or view these files, you need to be connected to the Internet and have the requisite plug-in applications installed on your computer. -

The Hearsay Rule As a Rule of Admission Revisited

THE HEARSAY RULE AS A RULE OF ADMISSION REVISITED Ronald J. Allen* Twenty-four years ago I noted that the transmutation of the rule of hearsay from a rule of exclusion into a rule of admission presaged its death, and I did not mourn its passing: [I]t is only a marginal overstatement to say that today, at least in civil cases, the hearsay rule applies in any robust fashion only to available nonparty witnesses within the subpoena power of the court. And it does not apply to them very rigorously. There are numerous exclusions from the definition of hearsay, twenty-seven formal exceptions, and two provisions explicitly encouraging the ad hoc creation of exceptions, an encouragement, it should be noted, of which much has been made. Moreover, hearsay exceptions, once formed, remain. To my knowledge, there are virtually no examples of hearsay exceptions being eliminated; the dynamic is one of ever-increasing scope for the exceptions . The Federal Rules, in concert with modern discovery principles, are quite clearly the harbinger of [the rule’s] demise. My instinct is that it is a death well-deserved, and after a burial suitable to its station, the hearsay rule should be allowed to lie quietly, undisturbed, for eternity.1 Like the report of Mark Twain’s death, my announcement of the passing of hearsay was exaggerated. It (and I refer here to the federal hearsay rule) remains more or less as it was twenty-four years ago, having undergone only slight expansion.2 * John Henry Wigmore Professor of Law, Northwestern School of Law; Fellow, Procedural Law Research Center, and President, Board of Foreign Advisors, Evidence Law and Forensic Science Institute, China University of Political Science and Law, Beijing. -

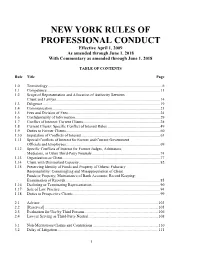

RULES of PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT Effective April 1, 2009 As Amended Through June 1, 2018 with Commentary As Amended Through June 1, 2018

NEW YORK RULES OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT Effective April 1, 2009 As amended through June 1, 2018 With Commentary as amended through June 1, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Rule Title Page 1.0 Terminology ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Competence .................................................................................................................... 11 1.2 Scope of Representation and Allocation of Authority Between Client and Lawyer .......................................................................................................... 14 1.3 Diligence ........................................................................................................................ 19 1.4 Communication .............................................................................................................. 21 1.5 Fees and Division of Fees .............................................................................................. 24 1.6 Confidentiality of Information ....................................................................................... 29 1.7 Conflict of Interest: Current Clients............................................................................... 38 1.8 Current Clients: Specific Conflict of Interest Rules ...................................................... 49 1.9 Duties to Former Clients ................................................................................................ 60 1.10 Imputation of Conflicts -

Military Rules of Evidence

PART III MILITARY RULES OF EVIDENCE SECTION I GENERAL PROVISIONS Rule 101. Scope the error materially prejudices a substantial right of (a) Scope. These rules apply to courts-martial the party and: proceedings to the extent and with the exceptions (1) if the ruling admits evidence, a party, on the stated in Mil. R. Evid. 1101. record: (b) Sources of Law. In the absence of guidance in (A) timely objects or moves to strike; and this Manual or these rules, courts-martial will apply: (B) states the specific ground, unless it was (1) First, the Federal Rules of Evidence and the apparent from the context; or case law interpreting them; and (2) if the ruling excludes evidence, a party in- (2) Second, when not inconsistent with subdivi- forms the military judge of its substance by an offer of proof, unless the substance was apparent from the sion (b)(1), the rules of evidence at common law. context. (c) Rule of Construction. Except as otherwise pro- (b) Not Needing to Renew an Objection or Offer of vided in these rules, the term “military judge” in- Proof. Once the military judge rules definitively on cludes the president of a special court-martial the record admitting or excluding evidence, either without a military judge and a summary court-mar- before or at trial, a party need not renew an objec- tial officer. tion or offer of proof to preserve a claim of error for appeal. Discussion (c) Review of Constitutional Error. The standard Discussion was added to these Rules in 2013. The Discussion provided in subdivision (a)(2) does not apply to er- itself does not have the force of law, even though it may describe rors implicating the United States Constitution as it legal requirements derived from other sources. -

Published As Chapter 8 in International Arbitration and International Commercial Law: Synergy, Convergence and Evolution

Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 2011 "Competence-Competence and Separability-American Style", published as Chapter 8 in International Arbitration and International Commercial Law: Synergy, Convergence and Evolution Jack M. Graves Touro Law Center Yelena Davydan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/scholarlyworks Part of the Commercial Law Commons, Contracts Commons, Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons, International Law Commons, and the International Trade Law Commons Recommended Citation International Arbitration and International Commercial Law: Synergy, Convergence and Evolution Chapter 8 – Competence-Competence and Separability-American Style Edited by S. Kroll, L.A. Mistelis, et. al. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jack Graves* & Yelena Davydan** CHAPTER 8 COMPETENCE-COMPETENCE AND SEPARABILITY – AMERICAN STYLE 1. INTRODUCTION The doctrines of “separability” and “competence-competence” are often called the cornerstones of international commercial arbitration. Distinct, but very much related, these two doctrines serve, hand in glove, to maximize the effectiveness of arbitration as an efficient means of resolving international commercial disputes and to minimize the temptation and effect of delay tactics. Each of these principles arises from the autonomous nature of the arbitration agreement, even when included as a clause within a broader “container” agreement. “Competence-competence” provides an arbitral tribunal with the power to rule on its own jurisdiction,1 thus avoiding any need to wait for a court determination of the issue and allowing the tribunal to move expeditiously to decide the merits of the parties’ broader contract dispute.