Sprinting Performance and Resistance-Based Training Interventions: a Systematic Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitch Muller – Mindsetfitness.Net

Complete EXERCISE GUIDE Mitch Muller – MindsetFitness.net Chest Exercises BB Bench Press / Incline Bench Press Special Notes: First retract your shoulder blades into the pad to “lock” your shoulders in place. This will ensure that the tension stays on your chest. Finish the movement with the elbows slightly bent. DB Bench Press / Incline Bench Press Special Notes: Same retraction technique of the shoulder blades as mentioned above. Lower the weight into a deep stretch of the chest. The DB’s should finish OUTSIDE of your shoulders, NOT ABOVE your shoulders “clicking” the weights together. The purpose is to keep tension in the chest throughout the entire range of motion. DB Fly / Incline Fly Special Notes: Retract Shoulder blades first. Open up the DB’s WIDE, making sure to not turn the movement into a press. Finish the exercise with the weights outside of the shoulders just like the DB chest press above. DB Incline Press Fly Special Notes: This movement emphasizes the negative portion (the lowering of the weights). Simple perform a regular negative rep for the fly, then tuck the DB’s into a press position (where you are stronger), press them up above your head and control the negative fly again. This movement is a combination of both a press and a fly. Great exercise when the chest is nearing fatigue. Machine Chest Press / Hammer Strength Chest Press Special Notes: Retract shoulder blades into pad and slide out in the seat slightly to get into a “locked” position. Shoulders do NOT move forward whatsoever during this movement. Focus your attention on the upper middle fibers of your chest and SQUEEZE. -

Edina Hornet

EDINA HORNET SUMMER STRENGTH TRAINING 1 HORNET SUMMER STRENGTH & CONDITIONING TABLE OF CONTENTS I. HORNET STRENGTH & CONDITIONING MANUAL pg.4-17 II. SUMMER STRENGTH TRAINING – 3 PHASES pg.18-30 III.STRENGTH TRAINING ROUTINES- a.) Multi-Set Barball pg.31 b.) Multi-Set Dumbbell pg.32 c.) Dumbbell Elevator pg.33 d.) Multi-Set Machine pg.34 e.) Pre-Exhaust pg.35 f.) Lower Body Routine pg. 36 IV.STRENGTH TRAINING- a.) The Rep pg.37-40 b.) Importance of Progression pg. 41-47 c.) Intensity & Time pg.48-50 d.) Supervision & Motivation pg.51-52 e.) Recording pg. 53 f.) In Season Training pg. 54 g.) Program Organization pg.55-58 h.) Upper Body pg. 59-60 i.) Lower Body pg.61-62 j.) Neck/ Midsection/ Arms pg. 63 k.) Strength Training Principles pg. 64 l.) Seven Strength Training Variables pg. 65-67 m.) How to Record pg. 68 n.) Manual Resistance pg. 69-89 V.CONDITIONING a.) Specificity of Conditioning pg. 90-102 b.) Warm-up Procedure pg. 103 c.) Interval Routines pg. 104-112 d.) Sample Five-Week Interval Programs pg. 112 e.) Maximum Results in Minimum Time pg. 113 f.) Short Shuffle pg. 114 g.) Up- Backs pg. 114 h.) The Ladder pg. 115 2 HORNET SUMMER STRENGTH & CONDITIONING HORNET SUMMER STRENGTH & CONDITIONING TABLE OF CONTENTS VI. SKILL DEVELOPMENT pg. 116-117 VII. FLEXIBILITY pg. 118-119 VIII. NUTRITION REST pg. 120-125 IX. THE MENTAL COMPONENT pg. 127-132 X. QUESTIONS & ANSWERS pg. 133-143 3 I. EDINA HORNET STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING The purpose of this manual is to provide you with a general overview of our conditioning philosophy. -

The Bench Press Fly's

www.dfwsportsmed.com AC Joint Injuries: Weight-Lifting Exercises to Avoid Adapted from Ollie Odebunmi, Demand Media The acromioclavicular joint, also known as the AC joint, is at the top most point of your shoulder where the collar bone attaches to the shoulder. AC joint injuries are caused by repetitive trauma, falls on the shoulder joint or certain weightlifting exercises. But you don't have to abandon your weightlifting program. Simply modify your technique and avoid the exercises that cause discomfort. The Bench Press Avoid full range of motion barbell or dumbbell bench presses. Excessive stress on the AC joint occurs when your elbows drop below your body on the downward motion. Using heavy weights compounds the problem. The bench press is often seen as a test of strength by weightlifters, and many do the exercise too frequently with near- maximal weights. Limit the stress on your AC joint by not bench pressing every week. Use a towel roll or do the bench press on the floor to prevent the elbows from dropping past the body. Fly’s Flat bench or incline bench dumbbell fly’s with dumbbells lowered in a wide arc out to the sides overextends the shoulder joints. The stress and risk of injury to the AC joint increases if your elbows drop below your body to get a full stretch of the pectorals. Machine fly’s gripping a bar or handles or with forearms against a pad also overextend your shoulder joints on the negative phase of the movement as your elbows travel beyond your shoulder joints. -

Full Body Workout Plan

WORKOUT PLAN Recommended Program For You: Full Body Routine 3x Per Week Since you’re still in your first year of consistent proper training, the fastest way for you to progress in the gym will be to follow a full body routine 3 times per week. This will maximize progressive overload on all of the key compound lifts and produce the most efficient results for you at your current stage. There are 2 different workouts you’ll be performing (workout A and workout B), and you’ll simply alternate back and forth between them on any 3 non-consecutive days of the week. That means week one would consist of workout ABA, week two would be BAB, then repeat. You should also aim to include 2-3 cardio sessions throughout the week. These can be done at any time as long as it isn’t immediately prior to weight training. Low intensity/long duration, high intensity/short duration or medium intensity/medium duration cardio are all acceptable forms and you can just choose based on preference. Cardio is not mandatory from a pure fat burning perspective (since this can technically be achieved through diet alone), but it’s still a good idea to include for the sake of overall physical/mental health and metabolic conditioning purposes. A few important notes about your workout plan… - All sets should be performed approximately 1-2 reps short of muscular failure. This means that you should continue each set until the point where, if you were to give a 100% all-out effort, you would only be able to complete 1-2 more reps in proper form. -

Training Phase: Quads Specialisation Shoulders and Arm Legs

Training Phase: Quads Specialisation Shoulders and Arm Exercise Sets Reps Tempo Rest Notes Week 1 Week 2 A1 Machine reverse fly 5 10 30X1 60 B1 Smith machine millatary press 4 8 60X0 45 B2 Db bent over laterals 4 12 6011 45 C1 Side laterals 5 10 3011 60 Last 4 sets are dropsets D1 One arm tricep extension 4 12 3012 45 Contract hard D2 One arm high cable curl 4 12 3012 45 Contract hard Weight 1 Weight 2 Weight 3 Weight 4 Legs Exercise Sets Reps Tempo Rest Notes Week 1 Week 2 A1 One leg seated leg curl 5 10 30X1 0 One extra set A2 One leg step ups 4 15 2010 60 B1 Hack squat - 3 drops each 4 12 4010 60 All out!! C1 Deficit Deadlifts 4 15 4010 75 Really squeeze glute D1 Lying leg curl 6 6 4012 30 Strict tempo eight 2 Weight 3 Weight 4 Back and Calves Exercise Sets Reps Tempo Rest Notes Week 1 Week 2 A1 Wide grip pull ups 6 6 30X0 0 A2 Narrow grip pull ups 6 10 60X0 60 B1 One arm cable row 4 12 3012 45 B2 Cable pullover 4 12 3011 45 C1 Barbell rows 6 10 40X0 60 D1 Standing calf raise 2+ lots 2010 90 10reps, 10sec rest up to heaviet weight then do 4 drop eight 2 Weight 3 Weight 4 Arms Exercise Sets Reps Tempo Rest Notes Week 1 Week 2 A1 Alternating db curl 4 12 3011 45 A2 Flat bench tricep extensions 4 12 3111 45 B1 Bicep pullups 5 6 60X1 60 B2 Db close grip press 5 6 41X0 60 C1 Machine curl 4 10 3010 45 C2 Machine tricep extension 4 12 3110 45 D1 Low cable curl 3 12 3010 45 D2 Overhead tricep extension 3 15 3110 45 eight 2 Weight 3 Weight 4 Chest and Abs Exercise Sets Reps Tempo Rest Notes Week 1 Week 2 A1 Flat db press 4 10 50X0 45 A1 Ab -

Weight Lifting Through Life: a Guide to Safe Weight Training John A

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Physical Therapy Scholarly Projects Department of Physical Therapy 2007 Weight Lifting through Life: A Guide to Safe Weight Training John A. Andrew University of North Dakota Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/pt-grad Part of the Physical Therapy Commons Recommended Citation Andrew, John A., "Weight Lifting through Life: A Guide to Safe Weight Training" (2007). Physical Therapy Scholarly Projects. 497. https://commons.und.edu/pt-grad/497 This Scholarly Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Physical Therapy at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physical Therapy Scholarly Projects by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WEIGHT LIFTING THROUGH LIFE: A GUIDE TO SAFE WEIGHT TRAINING by John A. Andrew Master of Physical Therapy University of North Dakota, 1998 Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist National Strength and Conditioning Association, 1997 A Scholarly Project Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Department of Physical Therapy School of Medicine University of North Dakota in partial fulfilhnent of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Physical Therapy Grand Forks, North Dakota December, 2007 This Scholarly Project, submitted by John Andrew in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Physical Therapy from the University of North Dakota, has been read by the Advisor and Chaitperson -

10 Back Bent-Over Barbell Row

MONDAY SUPERSET WORKOUT A Superset #1 Sets Reps Chest Flat Barbell Press 2 8 - 10 Back Bent-Over Barbell Row 2 8 - 10 Superset #2 Sets Reps Chest Incline Barbell Press 2 8 - 10 Back Machine Lat Pull Downs 2 8 - 10 Superset #3 Sets Reps Chest Flat Barbell Press 2 8 - 10 Back Bent-Over Barbell Row 2 8 - 10 Superset #4 Sets Reps Chest Pec Machine Fly 2 8 - 10 Back Dumbbell Shrugs 2 8 - 10 *the above chest and back exercises are performed in a superset fashion. Set #1 is flat Barbell Press. Set #2 is Bent Over Barbell Row. These sets are performed back-to-back with no more than 1-minute rest between each set. Alternate between each exercise until you have completed 3 sets of each exercise. TUESDAY OFF / REST DAY WEDNESDAY LEGS / ABS Exercise Sets Reps Legs Hack Squat 4 8 – 10 Stiff Leg Dead Lifts 4 8 – 10 Machine leg Extensions 3 8 – 10 Abs Kneeling Crunch 3 8 – 10 Flat Bench Lying Leg Raises 3 8 – 10 THURSDAY SUPERSET WORKOUT B Superset #1 Sets Reps Chest Flat Dumbbell Press 2 8 – 10 Back Single Arm Dumbbell Rows 2 8 – 10 Superset #2 Sets Reps Chest Incline Dumbbell Press 2 8 – 10 Back Sitting Cable or Machine Rows 2 8 – 10 Superset #3 Sets Reps Chest Flat Dumbbell Press 2 8 – 10 Back Wide Grip Pull Ups 2 8 – 10 Superset #4 Sets Reps Chest Dumbbell Pec Fly 2 8 – 10 Back Machine Lat Pull Downs 2 8 – 10 FRIDAY OFF / REST DAY SATURDAY ARMS AND SHOULDERS Exercise Sets Reps Shoulders Dumbbells Over Press 4 8 – 10 Dumbbell Side Lateral Raises 4 8 – 10 Biceps Dumbbell Curls 3 8 – 10 Preacher Curl 3 8 – 10 Triceps Close Grip Bench Press 3 8 -10 Cable Push Down with Rope 3 8 – 10 SUNDAY OFF / REST DAY Optimum Mass Version 2.0 . -

Week 23 Workouts

WEEK 23 WORKOUTS DAY 155: TRICEPS, BICEPS, SWIM EXERCISE SETS REPS SET 1 SET 2 SET 3 TRISET Triceps extension 3 20 Bench dip 3 to failure Close-grip push-up 3 to failure SUPERSET Reverse-grip cable push-down 3 12 Underhand cable curl 3 12 3 double Hammer curl 15 dropsets SWIMMING MAIN SET 1000 meters pull with buoy at Ironman effort 3 sets of 500 meters pull with buoy and paddles at Ironman effort 1000 meters swim at Ironman effort www.bodybuilding.com/manofiron WEEK 23 WORKOUTS DAY 156: SHOULDERS, ABS EXERCISE SETS REPS SET 1 SET 2 SET 3 SUPERSET Face-pull 3 12 Smith machine upright row 3 12 SUPERSET Rear delt raise 3 20 Seated dumbbell lateral raise 3 20 SUPERSET Incline cable front raise 3 12 Standing cable front raise 3 12 Using pronated (palms down) grip TRISET Sit-up 3 10 Crunch with 10 sec. hold at top 3 10 Hanging leg raise 3 to failure www.bodybuilding.com/manofiron WEEK 23 WORKOUTS DAY 157: REST OR OPTIONAL RECOVERY SWIM SWIMMING MAIN SET 2 sets of 400 meters pull, 1 min. between sets but no rest before next 1000 meters 1000 meters at 8/10 effort COOL-DOWN 500 meters pull, easy pace DAY 158: CHEST, RUN EXERCISE SETS REPS SET 1 SET 2 SET 3 SET 4 Incline machine press 4 8 Bench press 4 15 Decline bench press 3 15 3 double Machine fly 20 dropsets Incline guillotine press 3 15 RUNNING WARM-UP 1 mile, easy pace MAIN SET 4 miles at target marathon pace or 6/10 effort. -

Lower Body Fat Loss Workout MISSION AESTHETICS

THE TOOLS YOU NEED TO BUILD THE BODY YOU WANT® Store Workouts Diet Plans Expert Guides Videos Tools MISSION AESTHETICS: 10 WEEK DEFINED & SHREDDED WORKOUT The mission is simple: Get shredded and Main Goal: Lose Fat Equipment: Barbell, Bodyweight, show off the physique you’ve always dreamed Training Level: Intermediate Cables, Dumbbells, Machines of. And with the Mission Aesthetics 10 week workout, we’ll show you the way. Program Duration: 10 Weeks Target Gender: Male & Female Days Per Week: 4 Day Author: Josh England Link to Workout: https://www.muscleandstrength.com/ workouts/mission-aesthetics-10-week-fat-loss-workout Time Per Workout: 60-90 Mins Day 1: Full Body Fat Loss Workout Exercise Sets Reps Deadlift 4 3 Seated Cable Row 3 8 Lat Pull Down 3 12 Push Up 3 15 Walking Bodyweight Lunges 3 15 Each Day 2: Rest/Active Recovery Cardio On rest days you have the option to take the day completely off or perform some form of active recovery. If you’re the type of person who goes stir-crazy without a workout during the day, it is recommended to do some light recovery walking and at-home core work on this day. Day 3: Upper Body Fat Loss Workout Exercise Sets Reps Seated Shoulder Press 4 6 Incline Bench Press 4 6 A1. Machine Lateral Raise 3 12 A2. Machine Fly 3 12 Rear Delt Fly 3 12 Dumbbell Row 3 8 Day 4: Lower Body Fat Loss Workout Exercise Sets Reps Barbell Squat 4 3 Leg Press 3 10 Dumbbell Stiff Leg Deadlift 3 8 Leg Extension 3 15 Leg Curl 3 15 Calf Raise 4 20 Day 5: Rest/Active Recovery Day On rest days you have the option to take the day completely off or perform some form of active recovery. -

The Perfect Summer Shred Workouts and Cardio

THE PERFECT SUMMER SHRED WORKOUTS AND CARDIO 1 | | THE PERFECT SUMMER SHRED: WORKOUTS AND CARDIO THE RULES These rules apply to all THE PERFECT SUMMER SHRED: of the workouts. WORKOUTS AND CARDIO * The sets and reps don’t include warm-up If you’re looking to burn down the old you on a tight deadline this summer, then send sets. Perform as many those old straight-set workouts packing! To get ultra-ripped, you need to amp up your as you need, but never overall training intensity. In this program, that means supersets, dropsets, clusters, and take your warm-ups density training. near muscle failure. • After warm-ups, Stick with this program for at least 4 weeks to give it the best chance to work. Along choose a weight that with the nutrition and supplementation guidelines outlined in the Cellucor Summer allows you to approach Shred Superfeature, it should be enough to kick-start some serious progress. While this muscle failure by the target rep listed. workout will increase your conditioning, the primary goal is to to get you leaner Adjust the weight by boosting your metabolism based on the parameters outlined in the 5 Musts of The on follow-up sets as Fat-Loss Workout article. necessary. • Train past failure using However, be warned that this program is fairly advanced as written. Adjust the volume advanced intensity and intensity downward depending on your ability if you feel like you’re struggling to boosters only where recover between workouts. noted in the program. LIFTING: TWO-ON/ONE-OFF SPLIT CARDIO: FIVE-ON/TWO-OFF SPLIT • Beginning-level lifters MONDAY MONDAY should reduce the training volume by Chest, Triceps, Abs HIIT eliminating 1-2 exercises from the TUESDAY TUESDAY middle of the routine Legs Steady-State Cardio and reduce the loads lifted. -

WEEK 22 WORKOUTS DAY 148: BICEPS, TRICEPS, SWIM EXERCISE SETS REPS SET 1 SET 2 SET 3 SUPERSET Seated EZ-Bar Curl 3 10 Standing EZ-Bar Curl 3 10

WEEK 22 WORKOUTS DAY 148: BICEPS, TRICEPS, SWIM EXERCISE SETS REPS SET 1 SET 2 SET 3 SUPERSET Seated EZ-bar curl 3 10 Standing EZ-bar curl 3 10 High pulley cable curl 3 dropsets 15 TRISET Two-arm triceps cable kick-back 3 10 Overhead cable extension 3 10 Close-grip push-up 3 to failure SWIMMING WARM-UP 10 sets of 50 meters swim, 15 sec. rest between sets MAIN SET 300 meters head-lead flutter kick on side, alternating sides every 25 meters 2 sets of 500 meters pull with big toes connected and no kicking. Keep it easy, rest as needed between sets. 10 sets of 50 meters swim, strong pace, 15 sec. rest between sets COOL-DOWN 100 meters, easy pace www.bodybuilding.com/manofiron WEEK 22 WORKOUTS DAY 149: LEGS, BIKE EXERCISE SETS REPS SET 1 SET 2 SET 3 SUPERSET Hack squat 3 15 Bodyweight squat on BOSU ball 3 to failure CIRCUIT 3 rounds Leg extension 3 15 Hamstring curl 3 15 Walking lunge 3 to failure Standing calf press 3 15 CYCLING WARM-UP 15 min., easy pace MAIN SET 3 rounds 15 min. at 200-210 watts or 8/10 effort 5 min. easy spin COOL-DOWN 15 min., easy pace www.bodybuilding.com/manofiron WEEK 22 WORKOUTS DAY 150: REST OR RECOVERY SWIM SWIMMING MAIN SET 9 sets of 50 meters, limiting strokes to work on kicking on side, and stroke power: 50 meters in only 6 strokes 50 meters in only 8 strokes 50 meters in only 10 strokes 50 meters, easy swim, counting your strokes (you’ll need this for the next set) 5 sets of 500 meters, using 2 strokes less per 50 meters than you did in easy swim. -

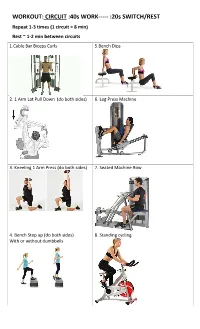

WORKOUT: CIRCUIT :40S WORK---:20S SWITCH/REST

WORKOUT: CIRCUIT :40s WORK----- :20s SWITCH/REST Repeat 1-3 times (1 circuit = 8 min) Rest ~ 1-2 min between circuits 1.Cable Bar Biceps Curls 5.Bench Dips 2. 1 Arm Lat Pull Down (do both sides) 6. Leg Press Machine 3. Kneeling 1 Arm Press (do both sides) 7. Seated Machine Row 4. Bench Step up (do both sides) 8. Standing cycling With or without dumbbells WORKOUT: AMRAP Complete as many reps/rounds as possible in _____ min 1. 15 Cal cycle 2. 15 Dumbbell Thrusters 3. 15/15 Skater Hops 4. 10 Incline Plyo Push ups 5.10/10 Bench Hop Over Choose a time amount, such as 4, 6, or 8 minutes. Complete as many rounds of the list as possible in that time. Choose a short time to stay in a high intensity zone. Choose a longer time to make it a lower intensity zone. WORKOUT: Tabata Each A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H for :20s work & :10s rest = 4 min + 1 min rest = 5 min A. Feet Over Bench Hops B. Bench Step ups Right leg C. Bench Step ups Left leg D. Dumbbell Push Press E. Dumbbell Swing F. Table Top Toe Taps G. Kneeling Slam H. Ball Sit ups Complete each exercise for :20s, then rest for :10s. Go through the list in order. This will take 4 minutes to complete. Rest for 1 min and repeat as many times as desired. WORKOUT: STRENGTH – LOWER BODY Low reps/Heavy weight/Long rest 1.Wide Stance Leg Press 2.Sandbag Squat 2 x 10/10 light to moderate (:30 rest) 4 x 8-10 (:60 rest) 3 x 6-8 moderate to hard (:60 rest) 3.