Syed-2020-Security-Threats-To-CPEC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparatory Survey Report on the Project for Construction and Rehabilitation of National Highway N-5 in Karachi City in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan

The Islamic Republic of Pakistan Karachi Metropolitan Corporation PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR CONSTRUCTION AND REHABILITATION OF NATIONAL HIGHWAY N-5 IN KARACHI CITY IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN JANUARY 2017 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY INGÉROSEC CORPORATION EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. EI JR 17-0 PREFACE Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) decided to conduct the preparatory survey and entrust the survey to the consortium of INGÉROSEC Corporation and Eight-Japan Engineering Consultants Inc. The survey team held a series of discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, and conducted field investigations. As a result of further studies in Japan and the explanation of survey result in Pakistan, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste for their close cooperation extended to the survey team. January, 2017 Akira Nakamura Director General, Infrastructure and Peacebuilding Department Japan International Cooperation Agency SUMMARY SUMMARY (1) Outline of the Country The Islamic Republic of Pakistan (hereinafter referred to as Pakistan) is a large country in the South Asia having land of 796 thousand km2 that is almost double of Japan and 177 million populations that is 6th in the world. In 2050, the population in Pakistan is expected to exceed Brazil and Indonesia and to be 335 million which is 4th in the world. -

In the High Court of Sindh, Karachi

1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF SINDH, KARACHI Civil Revision Application No. 249 of 2011 M/s. Pakistan Steel Mills Corporation……Versus…Major (Rtd) Gulzar Husain. J U D G M E N T Date of hearing : 30TH March, 2018. Date of Judgment : 29th June, 2018. Applicant : Mirza Sarfraz Ahmed, advocate. Respondent : None present. >>>>>>>>> <<<<<<<<<< Kausar Sultana Hussain, J:- This Civil Revision Application under Section 115 C.P.C. assails judgment and decree dated 12.08.2011 and 02.12.2011 respectively, passed by the learned IIIrd Additional Sessions Judge Malir, Karachi, whereby Civil Appeal No. 15 of 2009, filed by the respondent was allowed and Judgment and Decree passed in Civil Suit No. 07 of 2005 filed by applicant for recovery of Rs. 145,569/- was set aside and suit was remanded to learned trial Court with the direction to provide equal opportunity to the parties. 2. A short factual background of the case is that the respondent Major (Rtd) Gulzar Hussain approached to the applicant M/s. Pak Steel Mills Corporation and requested for a residential accommodation, therefore, on 01.03.1997, on his request a house bearing No. L-12/2, situated in Steel Town was allotted to him on payment of monthly rent, in which respondent resided up to 10.6.1998, on which date he was shifted from House No. L-12/2 to G-39/2, thereafter on 24.12.1999 respondent was retired from the service of Pakistan Army, therefore, he was requested to vacate the said house and clear outstanding rent amount with utility charges. -

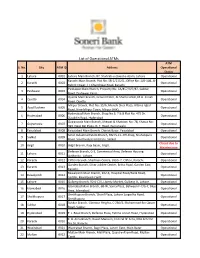

List of Operational Atms ATM S

List of Operational ATMs ATM S. No. City ATM ID Address Operational Status 1 Lahore 0001 Lahore Main Branch, 87, Shahrah-e-Quaid-e-Azam, Lahore. Operational Karachi Main Branch, Plot No: SR-2/11/2/1, Office No: 105-108, Al- 2 Karachi 0002 Operational Rahim Tower, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi Peshawar Main Branch, Property No: CA/457/3/2/87, Saddar 3 Peshawar 0003 Operational Road, Peshawar Cantt. Quetta Main Branch, Ground Floor, Al-Shams Hotel, M.A. Jinnah 4 Quetta 0004 Operational Road, Quetta. Mirpur Branch, Plot No: 35/A, Munshi Sher Plaza, Allama Iqbal 5 Azad Kashmir 0005 Operational Road, New Mirpur Town, Mirpur (AJK) Hyderabad Main Branch, Shop No.6, 7 & 8 Plot No. 475 Dr. 6 Hyderabad 0006 Operational Ziauddin Road, Hyderabad Gujranwala Main Branch, Khewat & Khatooni No: 78, Khasra No: 7 Gujranwala 0007 Operational 393, Near Din Plaza, G. T. Road, Gujranwala 8 Faisalabad 0008 Faisalabad Main Branch, Chiniot Bazar, Faisalabad Operational Small Industrial Estate Branch, BIV-IS-11--RH-Shop, Shahabpura 9 Sialkot 0009 Operational Road, Small Industrial Estate, Sialkot Closed due to 10 Gilgit 0010 Gilgit Branch, Raja Bazar, Gilgit. Maintenance Defence Branch, G-3, Commercial Area, Defence Housing 11 Lahore 0011 Operational Authority, Lahore. 12 Karachi 0012 Clifton Branch, Shadman Centre, Block-7, Clifton, Karachi. Operational Garden Branch, Silver Jubilee Center, Britto Road, Garden East, 13 Karachi 0013 Operational Karachi. Rawalpindi Main Branch, 102-K, Hospital Road/Bank Road, 14 Rawalpindi 0014 Operational Saddar, Rawalpindi Cantt. 15 Lahore 0015 Gulberg Branch, 90-B-C/II, Liberty Market, Gulberg III, Lahore. -

Brief Proposal

Brief Proposal Improvement of Quality Education in the Government Schools of Bin Qasim Town, Karachi Submitted By: Rotary Club, Gulshan-e-Hadeed, Karachi, Pakistan January 2009 Introduction: Rotary is a worldwide organization of more than 1.2 million business, professional, and community leaders. Members of Rotary clubs, known as Rotarians, provide humanitarian service, encourage high ethical standards in all vocations, and help build goodwill and peace in the world. There are 33,000 Rotary clubs in more than 200 countries and geographical areas. Clubs are nonpolitical, nonreligious, and open to all cultures, races, and creeds. As signified by the motto Service, Above Self, Rotary’s main objective is service — in the community, in the workplace, and throughout the world. (Source: http://www.rotary.org). Rotary’s Gulshan-e-Hadeed Club is a recently established member of Rotary’s District 3270 (Pakistan and Afghanistan). Gulshan-e-Hadeed is a well built area (union council) of Bin Qasim Town of City District Givernment Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan. 1 There are several ethnic groups living in Gulshan-e-Hadeed including Sindhis constituting majority,Punjabis, Muhajir, Kashmiris, Seraikis, Pakhtuns, Balochis, Memons, Bohras and Ismailis. It is located on the edge of the National Highway. Gulshan-e-Hadeed is at 30 minutes drive from Karachi’s Jinnah International Airport. The neighbor areas of Gulshan-e-Hadeed include Steel Town, Pipri and Shah Latif Town. Gulshan-e-Hadeed is divided in two phases (Phase-I and Phase-II). (Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gulshan-e-Hadeed) Background: Bin Qasim Town is a town located in the southeastern part of Karachi along the Arabian Sea and the Indus River delta. -

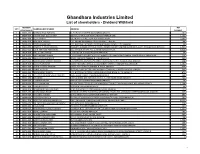

List of Shareholder-Dividend Withheld

Ghandhara Industries Limited List of shareholders - Dividend Withheld MEMBER NET SR # SHAREHOLDER'S NAME ADDRESS FOLIO PAR ID PAYABLE 1 00002-000 MISBAHUDDIN FAROOQI D-151 BLOCK-B NORTH NAZIMABADKARACHI. 461 2 00004-000 FARHAT AFZA BEGUM MST. 166 ABU BAKR BLOCK NEW GARDEN TOWN,LAHORE 1,302 3 00005-000 ALLAH RAKHA 135-MUMTAZ STREETGARHI SHAHOO,LAHORE. 3,293 4 00006-000 AKHTAR A. PERVEZ C/O. AMERICAN EXPRESS CO.87 THE MALL, LAHORE. 180 5 00008-000 DOST MUHAMMAD C/O. NATIONAL MOTORS LIMITEDHUB CHAUKI ROAD, S.I.T.E.KARACHI. 46 6 00010-000 JOSEPH F.P. MASCARENHAS MISQUITA GARDEN CATHOLIC COOP.HOUSING SOCIETY LIMITED BLOCK NO.A-3,OFF: RANDLE ROAD KARACHI. 1,544 7 00013-000 JOHN ANTHONY FERNANDES A-6, ANTHONIAN APT. NO. 1,ADAM ROAD,KARACHI. 5,004 8 00014-000 RIAZ UL HAQ HAMID C-103, BLOCK-XI, FEDERAL.B.AREAKARACHI. 69 9 00015-000 SAIED AHMAD SHAIKH C/O.COMMODORE (RETD) M. RAZI AHMED71/II, KHAYABAN-E-BAHRIA, PHASE-VD.H.A. KARACHI-46. 214 10 00016-000 GHULAM QAMAR KURD 292/8, AZIZABAD FEDERAL B. AREA,KARACHI. 129 11 00017-000 MUHAMMAD QAMAR HUSSAIN C/O.NATIONAL MOTORS LTD.HUB CHAUKI ROAD, S.I.T.E.,P.O.BOX-2706, KARACHI. 218 12 00018-000 AZMAT NAWAZISH AZMAT MOTORS LIMITED, SC-43,CHANDNI CHOWK, STADIUM ROAD,KARACHI. 1,585 13 00021-000 MIRZA HUSSAIN KASHANI HOUSE NO.R-1083/16,FEDERAL B. AREA, KARACHI 434 14 00023-000 RAHAT HUSSAIN PLOT NO.R-483, SECTOR 14-B,SHADMAN TOWN NO.2, NORTH KARACHI,KARACHI. -

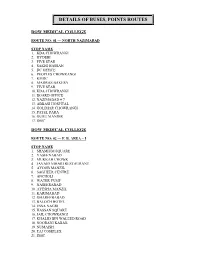

Details of Buses, Points Routes

DETAILS OF BUSES, POINTS ROUTES DOW MEDICAL COLLEGE ROUTE NO: 01 — NORTH NAZIMABAD STOP NAME 1. KDA CHOWRANGI 2. HYDERI 3. FIVE STAR 4. SAKHI HASSAN 5. DC OFFICE 6. PEOPLES CHOWRANGI 7. KMDC 8. MADRAS BAKERY 9. FIVE STAR 10. KDA CHOWRANGI 11. BOARD OFFICE 12. NAZIMABAD # 7 13. ABBASI HOSPITAL 14. GOLIMAR CHOWRANGI 15. PATEL PARA 16. GURU MANDIR 17. DMC DOW MEDICAL COLLEGE ROUTE NO: 02 — F. B. AREA – I STOP NAME 1. SHAMIUM SQUARE 2. YASEENABAD 3. MUKKAH CHOWK 4. JAVAID NIHARI RESTAURANT 5. AYOOB MANZIL 6. SAGHEER CENTRE 7. ANCHOLI 8. WATER PUMP 9. NASEERABAD 10. AYESHA MANZIL 11. KARIMABAD 12. GHAREEBABAD 13. BALOCH HOTEL 14. ESSA NAGRI 15. HASSAN SQUARE 16. JAIL CHOWRANGI 17. KHALID BIN WALEED ROAD 18. NOORANI KABAB 19. NUMAISH 20. TAJ COMPLEX 21. DMC OJHA INSTITUTE OF CHEST DISEASES ROUTE NO: 03 — FIVE STAR STOP NAME 1. KMDC 2. TAHIR VILLA 3. FIVE STAR 4. SHIP-OWNER COLLEGE 5. FIVE STAR 6. TAHIR VILLA 7. AISHA MANZIL 8. KARIMABAD 9. AISHA MANZIL 10. WATER PUMP 11. ANCHOLI 12. SOHRAB GOTH 13. ABUL HASSAN ISPHANI ROAD 14. KANEEZ FATIMA SOCIETY 15. KHARADAR CHOWRANGI 16. SUCHCHAL GOTH 17. OJHA DOW MEDICAL COLLEGE ROUTE NO: 04 — NORTH NAZIMABAD (MAYMAR) STOP NAME 1. SURJANI 2. 4-K CHOWRANGI 3. BABA MORR 4. BARADARI 5. DISCO MORR 6. ANDA MORR 7. QALANDARIA CHOWK 8. SHIP-OWNER COLLEGE 9. ABDULLAH COLLEGE 10. MATRIC BOARD OFFICE 11. A.O. CLINIC 12. NAZIMABAD PETROL PUMP 13. WOMEN COLLEGE 14. PATEL PARA 15. GURU MANDIR 16. SOLDIER BAZAR 17. -

The Social Effects of Drone Warfare on the F.A.T.A. and Wider Pakistan

THE SOCIAL EFFECTS OF DRONE WARFARE ON THE F.A.T.A. AND WIDER PAKISTAN Stephen Pine, January 2016 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the MA degree in Development and Emergency Practice, Oxford Brookes University The Social Effects of Drone Warfare on the F.A.T.A. and Wider Pakistan Abstract The FATA (Federally Administered Tribal Areas) of Pakistan have a long history of conflict and have been used as something of a proving ground for U.S. drones, operated jointly by the USAF (United States Air Force) and the CIA. This dissertation aims to evaluate the social effects of drone strikes and drone surveillance upon the civilian population of the FATA as well as other regions of Pakistan. Through statistical correlative analysis this dissertation finds that, far from achieving the aim of eliminating militancy within the FATA, drone strikes have acted as a recruitment tool for the Pakistani Taliban (TTP) and have harmed the local civilian population. FATA residents have been caught in a deadly cycle of drone strikes followed by militant revenge-attacks which have often been known to focus on ‘softer’ civilian targets. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of the data within this dissertation reveals that even the basic functioning of schools within the FATA has been affected, with both teachers and students hesitant to attend for fear of attack. Drone strikes in the region have also led to financial insecurity for families as they have lost their male ‘bread-winners’. This has been compounded by the destruction of family property and assets. Furthermore, local residents have been found to have developed mental health problems and, in many cases, display clear symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). -

IIED DENSITY STUDY 04 Cases of Housing in Karachi

IIED DENSITY STUDY 04 Cases of Housing in Karachi Final Report January 2010 Initiator and Research Supervisor Architect Arif Hasan Research Partner An assignment undertaken by the Urban Research and Design Cell (URDC) Department of Architecture and Planning, NED University of Engineering and Technology, (DAP-NED-UET), Karachi Research Team Members Assoc. Prof. Architect Asiya Sadiq Asst. Prof. Masooma Shakir Architect Suneela Ahmed Engr. Mansoor Raza 4th and 5th year Architecture Students, DAP-NED-UET Arif Hasan, Architect and Planning Consultant; email: [email protected] and Urban Research and Design Cell, NED University Karachi; email: [email protected] Table of Contents List of Tables List of Drawings A. Introduction • Objectives • Research Methodology B. Case Studies Case 1: Khuda ki Basti-3 (KKB-3) • Physical Description • Planning, Jurisdiction, the laws • Planning type: concepts • The street as interface between private and public and its usage • Open spaces and their use • Infrastructure conditions / determinants • Economic support in planning: Residential and commercial land use distribution • Houses in KKB • Social set up Statistical Analysis Photographic Documentation Case 2: Nawalane (NL) • Physical Description • Planning, Jurisdiction, the laws • Planning type: concepts • The street as interface between private and public and its usage • Open spaces and their use • Infrastructure conditions / determinants • Economic support in planning: Residential and commercial land use distribution • Condition of Houses • Social -

University of Karachi Karachi List of Principals Government/Private

UNIVERSITY OF KARACHI KARACHI LIST OF PRINCIPALS GOVERNMENT/PRIVATE COLLEGES S.No. NAME OF COLLEGE WITH ADDRESS 1. Prof. Rana Yasmeen, Principal, Abdullah College for Women, North Nazimabad, Karachi 2. Prof. A.B. Awan, Principal, Adamjee Government Science College, Off Business Recorder Road, Karachi 3. Prof. Ghaffar Shaikh, Principal, Aisha Bawani College No.2, Tufail N.H. Shaheed Road, Shahrah-e-Faisal, Karachi. 4. Prof. Anjum Abbas, Principal, A.P.W.A. College for Women F.B. Area, Karimabad, Karachi. 5. Prof. Zahida Tasneem, Principal, Allama Iqbal Govt. Girls College, Shah Faisal Colony No.2, Karachi. 6. Prof. Jameel Ahmed, Principal, Allama Iqbal Govt. Boys College, Shah Faisal Colony No.2, Karachi. 7. Prof. Khalid Memon, Principal, Allama Iqbal Govt. Boys College No.2, Shah Faisal Colony No.2, Karachi. 8. Prof. Piyar Ali Lalani, Principal, Govt. City College Opp: Ziauddin Hospital, F.B. Area, Karachi. 9. Prof. Shuaj ul Islam, Principal, Govt. City College No.2, Opp: Ziauddin Hospital, F.B. Area, Karachi. 10. Prof. Razia Khokhar, Principal, Govt. College for Commerce & Economics Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi. 11. Prof. Naseem Shaikh, Principal, Govt. College for Commerce & Economics No.2 Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi. 12. Prof. Zubeda Baloch, Principal, Govt. Degree Science & Commerce College Gulshan-e-Iqbal ST Block-7, Opp: Safari Park, Karachi 13. Prof. Tahir Baig, Principal, Govt. Degree Science/Commerce College, Landhi/Korangi No.6, Karachi 1 14. Prof. Ziauddin, Principal, Govt. Degree Science/Commerce College No.2, Landhi/Korangi No.6, Karachi 15. Prof. Abdul Karim Mughal, Principal, Govt. College of Physical Education, University Road, Karachi. -

A Baseline Study Report of Social Cohesion and Resilience My Story, Our Voice - Youth Communication Through Appreciative Inquiry Approach

A Baseline Study Report of Social Cohesion and Resilience My Story, Our Voice - Youth Communication Through Appreciative Inquiry Approach February 2015 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary Chapter 1: Background of the Study 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Rational of the Study 1.3 Description of the Project Chapter 2: Methodology of the Study 2.1 Target Group 2.2 Survey Design 2.3 Data Management and Analysis Chapter 3: Detailed Analysis of Research Findings Youth attending public schools, private schools and Madrassas. Youth working to earn money Youth from different communities (clans, sects, religion, ethnicities) living together 3.1 Living with those who have different opinions or beliefs 3.2 Solving dis-agreements without fighting 3.3 Trusting adults to talk to about problems 3.4 Trusting friends to talk to about problems 3.5 Feeling part of a community 3.6 Doing activities outside homes 3.7 Helping people from their own community, but not from other communities 3.8 Getting treated fairly by people of other communities 3.9 Playing a part in influencing group decisions 3.10 Wanting to have the opinion of their own community above the opinion of other communities References Annex: 1 2 List of Acronyms Appreciative Inquiry AI Baseline Survey BLS Community Based Organisation CBO Citizen Police Liaison Committee CPLC District Education Officer DEO Executive District Officer EDO Federally Administered Tribal Areas FATA Focus Group Discussion FGD Key Informant Interviews KIIs Khyber Pakhtunkhwa KP Non-Governmental Organisation NGO Rahim Yar Khan RYK Social Cohesion & Resilience SCR Theory of Change ToC United Nations International Children Emergency Fund UNICEF 3 Executive Summary According to the United Nations International Children Emergency Fund (UNICEF) Strategic Plan 2013- 21, „the fundamental mission of UNICEF is to promote the rights of every child1, everywhere, in everything the organization does — in programmes, in advocacy and in operations‟. -

Understanding and Responding to Karachi's Drug Menace

Policy Brief Understanding and Responding to Karachi’s Drug Menace National Initiative against Organized Crime-Pakistan 1. Introduction With a population of over 16 million, Karachi is the largest city of Pakistan and 7th largest city in the world.1 It hosts Pakistan’s major port, which handled a record cargo volume of 52.49 million tons during the year 2016-17,2 including the Afghan transit trade.3 Besides being the provincial capital of Sindh, Karachi is also deemed as financial capital of the country for it contributes the largest chunk of revenue in the national exchequer. However neither the city’s population nor economic opportunities are evenly distributed. According to some accounts, a majority of Karachi’s population lives in urban slums, or katchi abadis. The city has one of the world’s highest population growth rates (it stood at 9 percent in 2010), which is primarily contributed by high rural-to-urban migration.4 This migration is not restricted to the Sindhi hinterland only, but interestingly Pashtuns from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan constitute the second highest ethnic group of the city after mohajirs.5 These immigrants mostly settle in the katchi abadis, dotting all six districts of the city. Every metropolis has an underbelly, hidden by a glitzy infrastructure. The slums exist under the radar with high-density population clustered together. These population clusters tend to be ethnic concentrates, due to the phenomenon of ‘chain migration’.6 This composite of ethnic concentration in unplanned slums restricts access of law enforcement due to loyalty factor as well as difficult urban geography. -

May 2019 MLM

VOLUME X, ISSUE 5, MAY 2019 JAMESTOWN FOUNDATION The Death of Libya’s Rising Shafi Iran's High Muhammad Wilayat Sinai Star: A Profile of Value Target in Burfat: Spokesman Misratan Europe—Habib Advocate for Osama al-Masri Leader Fathi Sindi and its Impact on Jaber al-Ka’abi Bashagha BRIEF Independence the Insurgency in from Pakistan Sinai MUHAMMAD ANDREW ANIMESH ROUL NICHOLAS A. HERAS FARHAN ZAHID MANSOUR MCGREGOR VOLUME X, ISSUE 5 | MAY 2019 The Mastermind of the Sri Lankan leader of the NTJ and the mastermind behind Easter Sunday Attacks: A Brief Sketch the mayhem, along with seven others pledging of Mohammed Zahran Hashim of allegiance to IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. National Thowheeth Jama’ath Two suicide bombings at the Shangri-La Hotel in Colombo were carried out by Hashim and Animesh Roul Mohammad Ibrahim Ilham of JMI (Ada Derana News [Colombo], May 21). The rest of the Following the April 21 Easter Sunday attacks on suicide bombers have since been identified, churches and hotels in Sri Lanka that killed over including Mohammad Ibrahim Inshaf (brother 250 people and injured many more, the Sri of Ilham), Mohamed Hasthun, Ahmed Muaz, Lankan authorities and a devastated populace and Abdul Latif Jameel Mohammed (News.Lk, are still left with troubling questions. How had May 21). Intriguingly, except for Hashim—who this unheard of ‘Islamic extremism’ reach its was clearly leading other members in that IS shores unnoticed and who nurtured this deadly fealty video—the other attackers covered their strain of jihad in the country? faces and dressed in black tunic and While initial investigations unearthed evidence monochrome headscarves.