Summary of the 2014-15 Climate Lecture Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let Me Just Add That While the Piece in Newsweek Is Extremely Annoying

From: Michael Oppenheimer To: Eric Steig; Stephen H Schneider Cc: Gabi Hegerl; Mark B Boslough; [email protected]; Thomas Crowley; Dr. Krishna AchutaRao; Myles Allen; Natalia Andronova; Tim C Atkinson; Rick Anthes; Caspar Ammann; David C. Bader; Tim Barnett; Eric Barron; Graham" "Bench; Pat Berge; George Boer; Celine J. W. Bonfils; James A." "Bono; James Boyle; Ray Bradley; Robin Bravender; Keith Briffa; Wolfgang Brueggemann; Lisa Butler; Ken Caldeira; Peter Caldwell; Dan Cayan; Peter U. Clark; Amy Clement; Nancy Cole; William Collins; Tina Conrad; Curtis Covey; birte dar; Davies Trevor Prof; Jay Davis; Tomas Diaz De La Rubia; Andrew Dessler; Michael" "Dettinger; Phil Duffy; Paul J." "Ehlenbach; Kerry Emanuel; James Estes; Veronika" "Eyring; David Fahey; Chris Field; Peter Foukal; Melissa Free; Julio Friedmann; Bill Fulkerson; Inez Fung; Jeff Garberson; PETER GENT; Nathan Gillett; peter gleckler; Bill Goldstein; Hal Graboske; Tom Guilderson; Leopold Haimberger; Alex Hall; James Hansen; harvey; Klaus Hasselmann; Susan Joy Hassol; Isaac Held; Bob Hirschfeld; Jeremy Hobbs; Dr. Elisabeth A. Holland; Greg Holland; Brian Hoskins; mhughes; James Hurrell; Ken Jackson; c jakob; Gardar Johannesson; Philip D. Jones; Helen Kang; Thomas R Karl; David Karoly; Jeffrey Kiehl; Steve Klein; Knutti Reto; John Lanzante; [email protected]; Ron Lehman; John lewis; Steven A. "Lloyd (GSFC-610.2)[R S INFORMATION SYSTEMS INC]"; Jane Long; Janice Lough; mann; [email protected]; Linda Mearns; carl mears; Jerry Meehl; Jerry Melillo; George Miller; Norman Miller; Art Mirin; John FB" "Mitchell; Phil Mote; Neville Nicholls; Gerald R. North; Astrid E.J. Ogilvie; Stephanie Ohshita; Tim Osborn; Stu" "Ostro; j palutikof; Joyce Penner; Thomas C Peterson; Tom Phillips; David Pierce; [email protected]; V. -

A Report on the Way Forward Based on the Review of Research Gaps and Priorities

A Report on the Way Forward Based on the Review of Research Gaps and Priorities Sponsored by the Environmental Working Group of the U.S. NextGen Joint Planning and Development Office Lead Coordinating Author Dr. Guy P. Brasseur NCAR This report can be accessed via the internet at the following FAA website http://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/aep/aviation_climate/ 1 Table of Contents Preface.……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Executive Summary..……………………………………………………………………………...7 Chapter 1…………………………………………………………………………………………12 Introduction Chapter 2…………………………………………………………………………………............17 Contrails and Induced Cirrus: Microphysics and Climate Impact Chapter 3…………………………………………………………………………………………24 Contrails and Induced Cirrus: Optics and Radiation Chapter 4…………………………………………………………………………………………28 Chemistry and Transport Processes in the Upper Troposphere and Lower Stratosphere Chapter 5…………………………………………………………………………………………35 Climate Impacts Metrics for Aviation Chapter 6…………………………………………………………………………………………40 The Way Forward References………………………………………………………………………………………..43 Appendix I: List of ACCRI Subject Specific Whitepapers…………………………………...49 Appendix II: ACCRI Science Meeting Agenda………………………………………………..50 Appendix III: List of ACCRI Science Meeting Participants……………………………………53 2 Author Team* Preface Authors: Mohan Gupta and Lourdes Maurice, FAA; Cindy Newberg, EPA; Malcolm Ko, John Murray and Jose Rodriguez, NASA; David Fahey, NOAA Executive Summary Author: Guy Brasseur, NCAR Chapter I Introduction Author: Guy Brasseur, NCAR -

A Prediction Market for Climate Outcomes

Florida State University College of Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Publications 2011 A Prediction Market for Climate Outcomes Shi-Ling Hsu Florida State University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/articles Part of the Environmental Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Natural Resources Law Commons, and the Oil, Gas, and Mineral Law Commons Recommended Citation Shi-Ling Hsu, A Prediction Market for Climate Outcomes, 83 U. COLO. L. REV. 179 (2011), Available at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/articles/497 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PREDICTION MARKET FOR CLIMATE OUTCOMES * SHI-LING HSU This Article proposes a way of introducing some organization and tractability in climate science, generating more widely credible evaluations of climate science, and imposing some discipline on the processing and interpretation of climate information. I propose a two-part policy instrument consisting of (1) a carbon tax that is indexed to a “basket” of climate outcomes, and (2) a cap-and- trade system of emissions permits that can be redeemed in the future in lieu of paying the carbon tax. The amount of the carbon tax in this proposal (per ton of CO2) would be set each year on the basis of some objective, non-manipulable climate indices, such as temperature and mean sea level, and also on the number of certain climate events, such as flood events or droughts, that occurred in the previous year (or some moving average of previous years). -

Putting Climate Change Defendants in the Hot Seat

GAL.HACKNEY.DOC 3/8/2010 12:21 PM NOTES FLIPPING DAUBERT: PUTTING CLIMATE CHANGE DEFENDANTS IN THE HOT SEAT BY RYAN HACKNEY* Can climate change plaintiffs use Daubert challenges to exclude testimony by defense experts? Since the Supreme Court announced the standard in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., it has been used almost exclusively to the benefit of defendants. There is no theoretical reason, however, why plaintiffs could not use Daubert challenges to exclude testimony by defense witnesses in a scientific field in which the great weight of scientific research supports the plaintiffs’ claims. It is likely that in many cases climate change litigation will present such a situation. This Note considers four ways in which plaintiffs may use the Daubert standard and the Federal Rules of Evidence to exclude and restrict defense testimony: challenge the witness, challenge the reliability of the evidence, challenge the fit of the evidence to the case, and challenge the conclusions a witness may draw from otherwise admissible evidence. Part II of this Note examines the field of climate change litigation and considers the kinds of scientific disputes that are likely to arise in future litigation. Part III looks at the Daubert standard and Rule 702 of the Federal Rules of Evidence. Part IV applies the Daubert standard to * Law Clerk to United States District Judge Sim Lake for the Southern District of Texas. J.D., University of Texas School of Law, 2009; A.B. and A.M., Harvard University, 1997. The author would like to thank Professor Wendy Wagner for her insight and enthusiasm during the writing of this paper. -

2012 Redacted Response

From: Gillis, Justin To: Andrew Dessler Subject: RE: thoughts on Heartland Leak w.r.t. cloud feedback Date: Thursday, March 08, 2012 11:23:54 AM Yes, he was making that complaint. "My papers get special treatment from the cabal," etc. etc. I have to say I read the reviews of the '11 paper, at your suggestion, and they looked completely professional and on-point to my unpracticed eye. -----Original Message----- From: On Behalf Of Andrew Dessler Sent: Thursday, March 08, 2012 12:07 PM To: Gillis, Justin Subject: Re: thoughts on Heartland Leak w.r.t. cloud feedback He's been trying to publish this, but it's been rejected at least twice and a third rejection is on the way (I think). Dick doesn't understand R^2 or, more likely, the argument is just a squirt of squids' ink designed to confuse. On Thu, Mar 8, 2012 at 10:20 AM, Gillis, Justin wrote: > He had choice words to say about your paper, by the way. "R-squared of .02! Can you believe that!" I take it that means he didn't like the width of your error bars, or some such... > > > > -----Original Message----- > From: On > Behalf Of Andrew Dessler > Sent: Thursday, March 08, 2012 11:18 AM > To: Gillis, Justin > Subject: Re: thoughts on Heartland Leak w.r.t. cloud feedback > >> I trust you're treating these e-mails in strictest confidence, as I will. > > yes, do not worry. > >> >> >> >> -----Original Message----- >> From: On >> Behalf Of Andrew Dessler >> Sent: Thursday, March 08, 2012 10:59 AM >> To: Gillis, Justin >> Subject: Re: thoughts on Heartland Leak w.r.t. -

NASA ADVISORY COUNCIL Earth Sciences Subcommittee

Earth Science Subcommittee October 10, 2014 NASA ADVISORY COUNCIL Earth Sciences Subcommittee October 10, 2014 Teleconference MEETING MINUTES _____________________________________________________________ Steven Running, Chair _____________________________________________________________ Lucia S. Tsaoussi, Executive Secretary 1 Earth Science Subcommittee October 10, 2014 Table of Contents Opening Remarks/Meeting Introduction 3 Earth Science Division Research Performance for Fiscal Year 2014 3 Adjourn 8 Appendix A - Attendees Appendix B - Membership roster Appendix C - Agenda Prepared by Elizabeth Sheley Zantech IT 2 Earth Science Subcommittee October 10, 2014 Friday, October 10, 2014 Opening Remarks/Meeting Introduction Dr. Lucia Tsaoussi, Executive Secretary of the Earth Science Subcommittee (ESS) of the NASA Advisory Committee (NAC), began the meeting by calling roll of the ESS members. Earth Science Division Research Performance for Fiscal Year 2014 Dr. Tsaoussi explained that the teleconference had been called with the purpose of evaluating NASA’s Earth Science Division (ESD) under the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) Modernization Act (GPRAMA). GPRAMA is a tool to improve the efficiency of all Federal agencies. As part of the GPRAMA process, NASA’s Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) committees and subcommittees provide required “expert external review” in evaluating the Agency’s work. Therefore, ESS was being asked to evaluate how ESD has demonstrated progress in meeting key science objectives in context of the resources invested. The 2014 GPRAMA review was to cover events in Fiscal Year 2014 (FY14). All activities considered must have been fully or partly funded by NASA, and results should have been reported by a peer- reviewed journal or some other noncontroversial, reliable source. ESS was to provide an official vote on each criterion, along with supporting text that identified any particularly noteworthy items. -

PUC Docket No. E-999/CI-14-643 OAH Docket No. 80-2500-31888 Clean Energy Organizations Exhibit ______

PUC Docket No. E-999/CI-14-643 OAH Docket No. 80-2500-31888 Clean Energy Organizations Exhibit ________ BEFORE THE MINNESOTA OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE HEARINGS 600 North Robert Street St. Paul, MN 55101 FOR THE MINNESOTA PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION 121 Seventh Place East, Suite 350 St Paul, MN 55101-2147 In the Matter of the Further PUC Docket No. E-999/CI-14-643 Investigation into Environmental and OAH Docket No. 80-2500-31888 Socioeconomic Costs Under Minnesota Statute 216B.2422, Subd. 3 REBUTTAL TESTIMONY OF DR. ANDREW DESSLER, Professor in the Department of Atmospheric Sciences Texas A&M University On Behalf of Clean Energy Organizations PUC Docket No. E-999/CI-14-643 OAH Docket No. 80-2500-31888 Clean Energy Organizations Exhibit ________ TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXPERT EXPERIENCE ............................................................................................. 1 II. OVERVIEW OF TESTIMONY .................................................................................. 2 III. SPECIFIC RESPONSES OR CORRECTIONS ......................................................... 4 A. Equilibrium Climate Sensitivity ........................................................................... 4 B. Temperature Data ................................................................................................. 8 C. No Evidence of a Warming “Hiatus” ................................................................. 15 D. Accuracy of Models ........................................................................................... 23 E. Extreme -

How Much Will the Planet Warm If Carbon Dioxide Levels Double? - the New York Times 23/7/20, 10:05

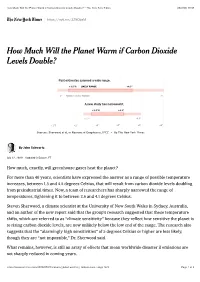

How Much Will the Planet Warm if Carbon Dioxide Levels Double? - The New York Times 23/7/20, 10:05 https://nyti.ms/2ZNQbeM How Much Will the Planet Warm if Carbon Dioxide Levels Double? Past estimates spanned a wide range. +1.5°C LIKELY RANGE +4.5° +1° HIGHLY LIKELY RANGE +6° A new study has narrowed it. +2.6°C +4.1° +2.2° +4.9° +1°C +2° +3° +4° +5° +6° Sources: Sherwood et al. in Reviews of Geophysics, IPCC • By The New York Times By John Schwartz July 22, 2020 Updated 3:54 p.m. ET How much, exactly, will greenhouse gases heat the planet? For more than 40 years, scientists have expressed the answer as a range of possible temperature increases, between 1.5 and 4.5 degrees Celsius, that will result from carbon dioxide levels doubling from preindustrial times. Now, a team of researchers has sharply narrowed the range of temperatures, tightening it to between 2.6 and 4.1 degrees Celsius. Steven Sherwood, a climate scientist at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, and an author of the new report said that the group’s research suggested that these temperature shifts, which are referred to as “climate sensitivity” because they reflect how sensitive the planet is to rising carbon dioxide levels, are now unlikely below the low end of the range. The research also suggests that the “alarmingly high sensitivities” of 5 degrees Celsius or higher are less likely, though they are “not impossible,” Dr. Sherwood said. What remains, however, is still an array of effects that mean worldwide disaster if emissions are not sharply reduced in coming years. -

NASA ADVISORY COUNCIL Earth Science Subcommittee

Earth Science Subcommittee August 28, 2015 NASA ADVISORY COUNCIL Earth Science Subcommittee August 28, 2015 Teleconference MEETING MINUTES _____________________________________________________________ Steve Running, Chair _____________________________________________________________ Lucia S. Tsaoussi, Executive Secretary 1 Earth Science Subcommittee August 28, 2015 Table of Contents Opening Remarks/Meeting Introduction 3 GPRAMA Discussion 3 Final Comments 7 Adjourn 7 Appendix A-Attendees Appendix B-Membership roster Appendix C-Agenda Prepared by Elizabeth Sheley Zantech IT 2 Earth Science Subcommittee August 28, 2015 Friday, August 28, 2015 Opening Remarks/Meeting Introduction Dr. Lucia Tsaoussi, Executive Secretary of the Earth Science Subcommittee (ESS) of the NASA Advisory Committee (NAC), began the meeting by calling roll of the ESS members. Dr. Tsaoussi explained that the teleconference had been called with the purpose of evaluating NASA’s Earth Science Division (ESD) under the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) Modernization Act (GPRAMA). The 2015 GPRAMA review was to cover events in Fiscal Year 2015 (FY15). All activities considered must have been fully or partly funded by NASA, and ESS was to provide an official vote on each criterion. The Science Mission Directorate (SMD) criteria for GPRAMA voting are as follows: • Green – Expectations for the research program fully met in context of resources invested. • Yellow – Some notable or significant shortfalls, but some worthy scientific advancements achieved. • Red – Major -

Potential Problems Measuring Climate Sensitivity from the Historical Record

15 MARCH 2020 D E S S L E R 2237 Potential Problems Measuring Climate Sensitivity from the Historical Record ANDREW E. DESSLER Department of Atmospheric Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas (Manuscript received 1 July 2019, in final form 26 November 2019) ABSTRACT This study investigates potential biases between equilibrium climate sensitivity inferred from warming over the historical period (ECShist) and the climate system’s true ECS (ECStrue). This paper focuses on two factors that could contribute to differences between these quantities. First is the impact of internal variability over the historical period: our historical climate record is just one of an infinity of possible trajectories, and these different trajectories can generate ECShist values 0.3 K below to 0.5 K above (5%–95% confidence interval) the average ECShist. Because this spread is due to unforced variability, I refer to this as the unforced pattern effect. This unforced pattern effect in the model analyzed here is traced to unforced variability in loss of sea ice, which affects the albedo feedback, and to unforced variability in warming of the troposphere, which affects the shortwave cloud feedback. There is also a forced pattern effect that causes ECShist to depart from ECStrue due to differences between today’s transient pattern of warming and the pattern of warming at 23CO2 equilibrium. Changes in the pattern of warming lead to a strengthening low-cloud feedback as equilibrium is approached in regions where surface warming is delayed: the Southern Ocean, eastern Pacific, and North Atlantic near Greenland. This forced pattern effect causes ECShist to be on average 0.2 K lower than ECStrue (;8%). -

CMOS Bulletin SCMO Volume 44 No. 6 December 2016

ISSN 1929-7726 (Online / En ligne) ISSN 1195-8898 (Print / Imprimé) CMOS BULLETIN Canadian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society SCMO La Société canadienne de météorologie et d’océanographie December / décembre 2016 Vol. 44 No. 6 Photo: Dan Weaver CMOS Bulletin SCMO Vol. 44, No.6 CMOS Bulletin SCMO Vol. 44, No.6 2 CMOS Bulletin SCMO Volume 44 No. 6. December 2016 - décembre 2016 Cover Page / Page couverture 4 Words from the President / Allocution du président Martin Taillefer 6 Articles As I See It: Acting on Climate Change—Maintaining the Momentum 8 by John Stone Article: Canada’s Wildfire Risk in the Midst of a Changing Climate 11 by Joanne Kunkel Article: Applications of CryoSat to Measure the Surface Elevation and Mass Balance of Canadian Arctic Glaciers and Ice Caps 13 by Luke Copeland, Laurence Gray, David Burgess From the Field: Lessons from the Field: Broken Gliders Make for an Entertaining Sailor 18 by Richard Davis and Anja Samardvic From the Field: Ph.D. Fieldwork in the Canadian High Arctic 20 by Dan Weaver Reports Seasonal Outlook for Winter 2016/2017 22 by Marko Markovic, Bertrand Denis and Marielle Alarie CMOS Business and News 50th Anniversary: Historical Highlights 24 by Richard Asselin 50th Anniversary: Golden Jubilee Fund 26 Book Reviews: Introduction to Modern Climate Change, Second Edition; A Farewell to Ice 27 Opportunities: CMOS Scholarships, Awards & Fellowships; Canada Research Chair—Tier II 30 Events: The Morley K. Thomas Meteorology History Archives; AMS 2017 Annual Meeting 37 Other CMOS News 40 CMOS Office / Bureau de la SCMO CMOS Bulletin SCMO "at the service of its members / au service de ses membres" P.O. -

Worst- and Best-Case Scenarios for Warming Less Likely, Groundbreaking Study Finds

SubscribemolecutrackLatest - Carbon Issues Capture Technologies Cart 0 Sign In | Newsletters We Focus on Clean Energy Solutions That Replace Hazardous and Carbon Intensive Fuel. OPEN molecutrack.com SHARE LATEST Ad Sign up for our free newsletters. Sign Up Molecutrack One-stop shop to manage your carbon removal portfolio and EARTH molecutrack.com Worst- and Best-Case ScenariosVisit Site for Warming LessADVERTISEMENT Likely, Groundbreaking Study Finds The research narrows the range for how much Earth’s average temperature may rise if CO2 levels are doubled By Chelsea Harvey, E&E News on July 23, 2020 READ THIS NEXT EARTH Seismologists Find a Silver Lining to Pandemic Lockdowns 2 hours ago — Christopher Intagliata POLICY & ETHICS Joining Pro-Business Groups Can Make Tech Firms Seem to Be Antiscience 17 hours ago — Naomi Oreskes PUBLIC HEALTH World War II's Warsaw Ghetto Holds Lifesaving Lessons for COVID-19 Credit: Caspar Benson Getty Images July 24, 2020 — Gary Stix How much warming will greenhouse gas emissions cause in the coming PUBLIC HEALTH years? It’s one of the most fundamental questions about climate change—and Coronavirus News Roundup: July 18-July 24 also one of the trickiest to answer. July 24, 2020 — Robin Lloyd | Opinion EVOLUTION Now, a major study claims to have narrowed down the range of possible World's Smallest Dinosaur is Probably a Lizard estimates. July 24, 2020 — Giuliana Viglione and Nature magazine It presents both good and bad news. The worst-case climate scenarios may be ARTS & CULTURE somewhat less likely than previous studies suggested. But the best-case Old Art Offers Agriculture Info climate scenarios—those assuming the least amount of warming—are almost July 24, 2020 — Susanne Bard certainly not going to happen.