Keel Machair/Menaun Cliffs SAC (Site Code: 001513)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

450 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

450 bus time schedule & line map 450 Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Pantry) View In Website Mode The 450 bus line (Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Pantry)) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Pantry): 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM (2) Louisburgh - Dooagh: 5:30 AM - 6:50 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 450 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 450 bus arriving. Direction: Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh 450 bus Time Schedule (Hudson's Pantry) Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Pantry) 15 stops Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:20 AM - 8:05 PM Monday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Dooagh Stop 530301 Tuesday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Keel Stop 530371 Wednesday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Dugort Stop 530391 Thursday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Dooniver Junction Stop 553011 Friday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Bunnacurry Stop 638031 Saturday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Cashel Stop 638041 Achill Sound Stop 631421 450 bus Info Direction: Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Mulrany Stop 638061 Pantry) Stops: 15 Newport Stop 638111 Trip Duration: 124 min Line Summary: Dooagh Stop 530301, Keel Stop Mill Street Stop 555711 530371, Dugort Stop 530391, Dooniver Junction Grove Park, Westport Stop 553011, Bunnacurry Stop 638031, Cashel Stop 638041, Achill Sound Stop 631421, Mulrany Stop Westport Quay Stop 557161 638061, Newport Stop 638111, Mill Street Stop 555711, Westport Quay Stop 557161, Murrisk Stop Murrisk Stop 500021 500021, Lecanvey Stop 545491, Kilsallagh Stop 557171, Louisburgh Stop 553111 -

TD,MEP, COCO Contacts.Xlsx

TD,MEP & CoCo Contact Details for MEP's, TD's and Councillors TD/MEP/CLLR Mr/Ms Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address4 Phone no Mobile Email Mayo Co Cllr Mr Al Mc Donnell Moorehall Ballyglass Claremorris Co. Mayo 094-9029039 086-8109499 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Austin Francis O'Malley Doughmackeon Roonagh P.O. Louisbourgh Co. Mayo 098-66418 087-2919477 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Blackie K Gavin Sion Hill Castlebar Co. Mayo 094-9022171 087-2490933 [email protected] W'Port Town Cllr Mr Brendan Mulroy 4 St.Patricks Tce. Westport Co. Mayo 087-2824702 [email protected] W'Port Town Cllr Mr Christy Hyland Distillery Court Westport Co Mayo 086-8342208 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Cyril Burke Premier Estate Maloney, I.P.I. Centre Breafy Road Castlebar Co. Mayo 087-6891821 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Damien Ryan Neale Road Ballinrobe Co. Mayo 094-9541444 [email protected] Co.Mayo TD Mr Dara Calleary TD Pearse Street Ballina Co Mayo 096-77613 [email protected] An Taoiseach Mr Enda Kenny TD Tucker Street Castlebar Co Mayo 094-9025600 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Eugene Mc Cormack 49 Knockaphunta Park Castlebar Co. Mayo 094-9023758 086-8101426 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Frank Durcan Westport Road Castlebar Co. Mayo 087-2589091 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Gerry Coyle Doolough Geesala Ballina Co. Mayo 097-82280 087-2441380 [email protected] Mayo Co Cllr Mr Henry kenny Straide Road Ballyvary Co. -

West Coast, Ireland

West Coast, Ireland (Slyne Head to Erris Head) GPS Coordinates of location: Latitude: From 53° 23’ 58.02”N to 54° 18’ 26.96”N Longitude: From 010° 13” 59.87”W to 009° 59’ 51.98”W Degrees Minutes Seconds (e.g. 35 08 34.231212) as used by all emergency marine services Description of geographic area covered: The region covered is the wild and remote west coast of Ireland, from Slyne Head north of Galway to Erris Head south of Sligo. It includes Killary Harbour, Clew Bay, Black Sod Bay, Belmullet, and the islands of Inishbofin, Inishturk, Clare, Achill, and the Inishkeas. It is an area of incomparable charm and natural beauty where mountains come down to the sea unspoilt by development. It is also an area without marinas, or easy access to marine services. Self-sufficiency is absolutely necessary, along with careful navigation around a rocky lee coastline in prevailing westerlies. A vigilant watch for approach of frequent Atlantic gales must be kept. Inishbofin is reported to be the most common stopover of visiting foreign-flagged yachts in Ireland, of which there are very few on the West coast. Best time to visit is May-September. 1 24 May 2015 Port officer’s name: Services available in area covered: Daria & Alex Blackwell • There are no marinas in the west of Ireland between Galway and Killybegs in Donegal, so services remain difficult to access. Haul out facilities are now available in Kilrush on the Shannon River and elsewhere by special arrangement with crane operators. • Visitor Moorings (Yellow buoy, 15 tons): Achill / Kildavnet Pier, Achill Bridge, Blacksod, Clare Island, Inishturk, Rosmoney (Clew Bay), Leenane. -

Mulranny Village Design Statement

Mulranny Village Design Statement Mulranny Village Design Statement An action of thE County MAyo HeritAgE PlAn Comhairle Contae Mhaigh Eo Mayo County Council table of Contents Foreword Foreword .....................................................................................................................................3 Section 1 introduction ...............................................................................................................................4 • introduction and background • Collaborative process • Setting the context Section 2 Mulranny now – issues and tasks ......................................................................................13 • Approaching Mulranny • the village centre • Pedestrian and traffic movement • the built environment • Signage, displayed fuels, discarded materials, bins and litter • the natural heritage and landscape • the beach and causeway Section 3 the Way Forward .....................................................................................................................24 EStAbliShing A VillAgE CEntrE • A promenade • A greenway hub • A quality built environment • Signage, displayed goods, litter etc. • traffic calming and footpaths iMProVing iMPortAnt foCAl PointS • the causeway and pedestrian routes to the sea • the school and church area • landscaping and the natural environment Section 4 Village Centre Design guidelines ........................................................................................40 • A contemporary approach • building lines and set -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

Mayo Walks County Mayo

1 Mayo Walks Sample walks are described. The meaning and background to placenames is given. In Irish culture, these describe geology, recall folklore, record history. They can contain words surviving in Scots Gaelic. Scots and Irish Gaelic were carefully kept as one, until the Gaelic Homeland was sundered. Full appreciation of this Brief would need a Gaelic-speaking guide, interacting with the Tour Guide. County Mayo Introduction County Mayo possesses great geographical contrasts for visitors. They may enjoy a variety of experiences, with the ocean as an ever-present backdrop. Awe-inspiring cliffs of the north coast and those on the western edge of Achill Island surely provide the country's finest coastal walks. More inland, the lonely Nephin Beg Range is a world apart from the very public (and rocky) Croagh Patrick. The name, Néifinn Beag , the Lesser Nephin, derives from Nemed . He was the son of Agnoman of Scythia . He sailed to Ireland from the Caspian Sea, in 1731 BC, in the chronology of the Historian, Priest and Poet, Seathrún Cétinn . Mweelrea (Cnoc Maol Réidh – the Smooth, Bare Hill), the highest peak in the county, is challenging. Waymarked routes provide, in all, more than 200km of walks through moorland, forest, farmland, villages and towns. History The earliest settlers were Neolithic farmers. They had occupied the area by c3000 BC. Stone buildings and burial places were mostly enveloped by the subsequent spread of Blanket Bog, a factor mainly of Climate Change. Some 160 Megalithic tombs or dolmens are known. Walkers more commonly encounter forts {duns ( dún – hill fort ) or raths ( ráth – ring fort )} dating from c800 BC to 1000 AD. -

The Famine in Mayo 1845-1850

The Famine in Mayo 1845-1850 A Mayo County Library Exhibition 1 Charles Edward Trevelyan, Assistant Secretary to the Treasury directed government relief measures during the famine, meticulously scrutinising all expenditure The Famine in Mayo 1845 - 1850 The Great Famine was one of the defining moments of Irish history. It marked a watershed in the history of the country causing a change so complete in the Irish social and economic fabric, that the people’s sensibilities would never be the same again. No longer could the Irish people trust to the land to provide constant sustenance. No longer could they rely on whatever security of tenure was allowed by the landlords, and more importantly they learned that their English political masters cared little for their plight. The Famine in Mayo is a portrait of the lives and deaths of the people as recorded by witnesses in books, newspapers and official records of that period. 1(a) The Famine in Mayo 1845 - 1850 The Potato Disease e first reports of blight appeared in September of 1845. For one third of the country’s population of eight million, the nutritious lumper potato was pratically the sole article of the diet. In County Mayo, it was estimated that nine tenths of the population depended on it. An acre and a half of land could provide enough potatoes to support a family for most of the year. Any other crops or animals the smallholder raised went to pay rent. A potato famine was a great calamity. THE POTATO CROP THE POTATO CROP PERSECUTION Mayo Constitution (11-11-1845) TO THE EDITOR OF AND STARVATION The Telegraph (19-8-1846) In some cases the damage is found, on THE CONSTITUTION Rathbane, 29th December, 1845 digging out the potatoes, to be only On Monday last upwards of 500 poor, partial, in other cases the injury and loss wretched, emaciated human beings are, very great. -

Chapter 2 Core and Settlement Strategy

Draft Mayo County Development Plan 2021-2027 CHAPTER 2 CORE AND SETTLEMENT STRATEGY 2.1 Introduction The Core Strategy and Settlement Strategy for the County Development Plan has been prepared through extensive collaboration between the Forward Planning team, Elected Members and all relevant sections of the Council. It has also been informed by the National Planning Framework (NPF), the Regional Spatial and Economic Strategy (RSES) for the Northern and Western Region, the UN Sustainable Goals and the Strategic Economic Drivers influencing the sustainable future growth of County Mayo over the lifetime of the plan and beyond. The challenge is to build on the unique dispersed settlement characteristics of Mayo, in order to provide a balance, link and synergy between the rural countryside and urban settlements of the County. This will be realised through the following vision for County Mayo and the strategic aims set out below. 2.2 Vision of County Mayo ‘To create a sustainable and competitive county that supports the health and well-being of the people of Mayo, providing an attractive destination, as a place in which to live, work, invest, do business and visit, offering high quality employment and educational opportunities within strong and vibrant sustainable communities, whilst ensuring a transition to a low carbon and climate resilient county that supports high environmental quality.’ 2.3 Strategic Aims The strategic aims which relate to the advancement of this vision, are set out hereunder for each chapter of Volume 1 of the County Development Plan. The Plan aims to build on previous successes and to strengthen Mayo’s strategic advantage as a county, to ensure that we meet the needs of our citizens, communities, built and natural environments, infrastructure and economic/employment development to their full potential, while combatting and adapting to climate change. -

CLEW 9 10 17 33 N59 Shannon 28 GREAT WESTERN Airport BAY 42 43 GREENWAY 30 N5 CLARE 23 Cork 4 31 ISLAND 5 WESTPORT 34 R330

Bangor Erris Ballina Crossmolina Bellacorick N59 N59 BALLYCROY NATIONAL 32 LOUGH CONN PARK Slievemore 14 Ballycroy ACHILL R315 ISLAND Croaghaun N59 Foxford 35 INISHBIGGLE R318 Minaun 2 Nephin Pontoon 1 3 6 LOUGH 19 22 25 FEEAGH 37 ACHILL CYCLE HUB 18 GREAT WESTERN Belfast GREENWAY LOUGH MULRANNY FURNACE 11 29 N59 R310 Corraun Hill KNOCK Sligo R312 NEWPORT AIRPORT CASTLEBAR 41 Ireland West N5 DUBLIN Airport, Knock 40 Swinford 8 R311 27 Dublin ACHILL BEG ISLAND Galway CLEW 9 10 17 33 N59 Shannon 28 GREAT WESTERN Airport BAY 42 43 GREENWAY 30 N5 CLARE 23 Cork 4 31 ISLAND 5 WESTPORT 34 R330 Roonagh 36 MURRISK N59 N84 Quay LOUISBURGH Croagh Patrick 20 21 16 N60 Viewing Points 24 Mountain Peaks Claremorris Woodland INISHTURK Ferries Fishing R331 DOOLOUGH Great Western Greenway National Coastal Route TAWNYARD 7 LOUGH N84 Mweelrea 26 Granuaile Cycle Trail 39 INISHBOFIN Ballinrobe LOUGH Cycle Hubs 15 Leenane MASK Beaches 13 R334 12 Walking Routes CLEGGAN 38 R336 GALWAY Letterfrack Cong R345 CONNEMARA NATIONAL PARK LOUGH CORRIB 41. National Museum of Ireland - Country Life, White Sea Horse, 36’ Bullet 300hp. Watersports & Activities Equestrian Centres / Turlough, Castlebar. T: 094 9031755 Skipper: Vinnie Keogh. Base: Westport. Farmers / Country Markets Walking Routes 1.Achill Island Scuba Dive Centre, Purteen Riding Centres W: www.museum.ie Op. Area: Clew Bay, Clare Island & Inishturk. Achill Country Market, Ted Lavelle’s, Cashel - Ballytoughey Loom, Clare Island Harbour, Achill Island. T: 087 2349884 Tel: 098 64865 / 26194 W: www.thehelm.ie every Friday from 11.00 to 13.00 Bothy Loop, Newport 22. -

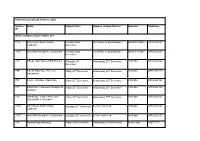

Please Click Here to Download Christmas Local Link Services 2020

Christmas Local Link Services 2020 Service Route Original Date: Propose change Date to: Operator Telephone ID Week commencing December 21st 3125 Achill South East Currane Tuesday 22nd No Change to day/schedule Michael O Haire (087)2202123 Castlebar December 3127 Achill NW Dooagh Keel Castlebar Tuesday 22nd No Change to day/schedule Michael O Haire (087)2202123 December 795 Kilkelly Urlar Tooreen Ballyhaunis Thursday 24th Wednesday 23rd December PortCabs (087)2202123 December 796 Kilkelly Aghamore Brickens Friday 25th December Wednesday 23rd December PortCabs (087)2202123 Ballyhaunis 797 Cross - Kilmaine - Ballinrobe Friday 25th December Wednesday 23rd December PortCabs (087)2202123 817 Shrahmore - Glenhest- Newport to Friday 25th December Wednesday 23rd December PortCabs (087)2202123 Westport 818 Islandeady - Fahy - Kilmeena - Friday 25th December Wednesday 23rd December PortCabs (087)2202123 Carrowholly to Westport 3125 Achill South East Currane Saturday 26th December Service cancelled PortCabs (087)2202123 Castlebar 3127 Achill NW Dooagh Keel Castlebar Saturday 26th December Service cancelled PortCabs (087)2202123 788 Attymachugh Attymass Friday 25th December Wednesday 23rd December Arrow Cabs (096)77777 Bonniconlon Ballina 799 Ballycroy to Belmullet Tuesday 22nd No change to day/schedule Michael Keane (086)8285628 December 801 Dorans Point via Ballycroy to Achill Thursday & Sunday No change to day/schedule Michael Keane (086)8285628 Sound 800 Dorans Point to Ballycroy Mon,Tues,Wed,Fri,Sat Cancelled Friday 25th & 26th Michael Keane (086)8285628 -

OBAIR LINKS NEWSLETTER–ISSUE 2 This Communication Is Coming from South West Mayo Dev Co OBAIR Links Funded by SICAP

OBAIR LINKS NEWSLETTER–ISSUE 2 This communication is coming from South West Mayo Dev Co OBAIR Links funded by SICAP. The Social Inclusion and Community Activation Programme (SICAP) 2018-2022 is funded by the Irish Government through the Department of Rural and Community Development and co- funded by the European Social Fund under the Programme for Employability, Inclusion and Learning (PEIL) 2014-2020 Issue 4th March 2020 South West Mayo Dev Co OBAIR Links Newsletter funded by SICAP 2020 South West Mayo Dev Co OBAIR Links Newsletter funded by SICAP 2020 South West Mayo Dev Co OBAIR Links Newsletter funded by SICAP 2020 South West Mayo Dev Co OBAIR Links Newsletter funded by SICAP 2020 South West Mayo Dev Co OBAIR Links Newsletter funded by SICAP 2020 South West Mayo Dev Co OBAIR Links Newsletter funded by SICAP 2020 South West Mayo Dev Co OBAIR Links Newsletter funded by SICAP 2020 jobsireland.ie https://www.jobsireland.ie/#/home (you need to register as a member with jobsireland to apply online for some of these positions or please contact your local employment office (intreo) in respect to the Community Employment positions) West Mayo CE Westport Rugby Club - CE Scheme - South West Mayo Development Company TEMPORARY Ref: #CES-2140789 No of positions: 1 Westport, County Mayo, Ireland This is a developmental opportunity, no experience necessary. Accredited training will be provided to support your career. Applicants should supply suitable character references and be prepared to complete a Garda vetting application form. Pitch Maintenance Painting Cleaning dressing rooms Setting up for matches Vehicle Damage Assessor Estimator Ref: #JOB-2140719 No of positions: 2 Ballina, County Mayo, Ireland Dublin, County Dublin, Ireland ACE Autobody is seeking to employ an experienced Estimator / Vehicle Damage Assessor (VDA) to work within their fast-paced Company. -

For Inspection Purposes Only. Consent of Copyright Owner Required for Any

Achill Sound Waste Water Discharge Application Attachment A.1 ATTACHMENT A.1 NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY 1. Waste Water discharge Licence (Background) Mayo County Council, Aras an Chontae, Castlebar, Co. Mayo is making an application to the Environmental Protection Agency (E.P.A.) for a waste water discharge licence for the Achill Sound Waste Water Treatment Plant at Achill Sound and Agglomeration in compliance with the Waste Water Discharge (Authorisation) Regulations 2007 (S.I. No. 684 of 2007). Under Regulation 5. (1), of the above Regulations, a water services authority shall at least 6 months before the date on which a waste water works becomes operational, make an application to the Agency for a licence authorising the waste water discharges from those works. The Achill Sound Waste Water Treatment Plant falls under this category as it is currently under construction and is due to be commissioned/operational by May 2010. Prior to the above plant no collection system or treatment plant existed in Achill Sound. 2. Description of Achill Sound Waste Water Works use. The Achill Sound Waste Water Treatment Plant (WWTP) has been designed to treat wastewater from an equivalent population of 1,200 persons and will be operated by Response- other Group. Treated effluent from the Plant will be dischargedonly. to the Atlantic Ocean (Primary Discharge Point) SW1 (P). any for The scheme as a whole includes for the construction of a scheme of Main Sewers to collect foul effluent from the Achill Sound agglomerpurposesation and convey the flow via 5 No. Pumping Stations, to the new Waste Water Treatment Plant, the names of which are as follows: - required Pumping Station Unique Point Code Name inspection owner St.