LC Paper No. CB(2)1598/18-19(02)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FG Hemisphere Associates LLC V. Democratic

CACV 373/2008 & CACV 43/2009 IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION COURT OF APPEAL CIVIL APPEAL NO. 373 OF 2008 & NO. 43 OF 2009 (ON APPEAL FROM HCMP NO. 928 OF 2008) BETWEEN FG HEMISPHERE ASSOCIATES LLC Plaintiff (Appellant) And DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO 1st Defendant (Respondent) CHINA RAILWAY GROUP (HONG KONG) 2nd Defendant LIMITED CHINA RAILWAY RESOURCES 3rd Defendant DEVELOPMENT LIMITED CHINA RAILWAY SINO-CONGO MINING 4th Defendant LIMITED CHINA RAILWAY GROUP LIMITED 5th Defendant And SECRETARY FOR JUSTICE Intervener Before: Hon Stock VP, Yeung JA and Yuen JA in Court Dates of Hearing: 28-31 July, 3-4 August 2009 Date of Handing Down Judgment: 10 February 2010 - 2 - J U D G M E N T Hon Stock VP: Introduction 1. In April 2003 arbitral awards were made in France and Switzerland against the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). France and Switzerland are parties to the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards. The plaintiff company has acquired the benefit of those awards and has obtained leave in Hong Kong to enforce the awards and injunctions to prevent third parties transferring assets allegedly due to the DRC. The DRC has claimed immunity from jurisdiction and from the process of execution. The Court of First Instance has set aside leave and the injunctions. This is an appeal from that decision. 2. This appeal addresses the questions whether an application for leave to enforce an arbitral award made under the New York Convention against a State impleads that foreign State; whether the law of Hong Kong requires application of the doctrine of absolute state immunity from jurisdiction and execution, as opposed to the restrictive doctrine; and whether by agreeing to refer a dispute to arbitration in a New York Convention country, to be conducted according to the Rules of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), a foreign State which is not a party to the Convention waives such state immunity from jurisdiction and execution to which it is otherwise entitled. -

SCHOOL of LAW NEWSLETTER School of Law City University of Hong Kong

Volume 15 No.1 March 2021 SCHOOL OF LAW NEWSLETTER School of Law City University of Hong Kong CityU School of Law is a premier law school with a history of excellence and the vision to become one of the great law schools in the Asia-Pacific region. The mission of the School is to provide students with an excellent education and to contribute to the advancement of knowledge. Through cooperation with other law schools and professional organizations, the School aims to foster an environment in which both students and staff develop and use their legal knowledge, professional skills and expertise for the benefit of Hong Kong and the region. Our Programmes on offer: Undergraduate and Taught Postgraduate Programmes Bachelor of Laws (LLB) Juris Doctor (JD) Postgraduate Certificate in Laws (PCLL) Master of Laws (LLM) Master of Laws in Arbitration and Dispute Resolution (LLMArbDR) Professional Doctorate Programme Doctor of Juridical Science (JSD) Research Degree Programmes Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Master of Philosophy (MPhil) For further information, please contact us at 3442-8008 @ [email protected] School of Law School of Law School of Law Website WeChat Facebook Contents 04 Focus of the Issue 06 School News 11 School Events 20 Research Centres 28 Student Achievements 29 Staff Achievements Published by School of Law, City University of Hong Kong, Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR. Please send your comments to [email protected] @2021 CityU School of Law. All rights reserved. SCHOOL OF LAW — NEWSLETTER — 3 FOCUS OF THE ISSUE Insights from the Inaugural Asian Law Schools Association Deans’ Congress on the Future of Law Schools and Legal Education The Asian Law Schools Association (ALSA) was 3. -

Foundation Yearbook 2019

CONTENTS 004 Message from the Chairman 007 Message from the Headmaster 008 Board of Directors 010 Sub-committees 015 Total Funds Raised 016 Endowment Fund 017 Annual Giving 018 Our Projects 020 Investment Report 022 Tiers of Recognition 030 Reunion Class Gifts 036 DBS 150th Anniversary 047 Acknowledgement of Event Sponsors 002 I I 003 MESSAGE from THE CHAIRMAN I am incredibly proud and excited to chair DBS Foundation and witness the 150th Anniversary of the School. The Most Revd. DR. PAUL KWONG Archbishop of Hong Kong Funds raised through various programmes of the Foundation have provided the School with excellent resources to nurture boys and develop them to their full potential. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to our directors and sub-committee members for their dedication and remarkable efforts throughout the year. I would also like to thank our Old Boys, parents and friends for their continued support and generous contribution. I hope you would enjoy reading this fifth Foundation report and pray that you would continue to support our work. 004 I Photo Credit: Diocesan Media Group of DBS MESSAGE from THE HEADMASTER RONNIE CHENG Class of '83 DBS has a long history of academic excellence and extra-curricular prowess, galvanised by a strong spirit connecting current and past students. We recognise and respect each other's differences within an environment which enables students to excel in their respective areas of strength. The generosity of our Old Boys, parents and friends of DBS, through their contribution to DBS Foundation, has provided the necessary resources which enable students to reach their full potential. -

Celebrating Our 30Th Anniversary

CityU Design and Production Services UP Volume 12 No.1 Feb 2018 produced by Interviewing Dean Howells Reporting on General Research Fund (GRF) / Early Career Scheme (ECS) Results Celebrating Our 30th Anniversary The Editorial Board would like to thank Agnes Kwok, Esther Wong as well as members of staff who helped in the preparation of the Newsletter. Dr Peter Chan (Editor in Chief), Ms Laveena Mahtani, Dr He Tianxiang Volume 11 No. 1 ∙ Feb 2018 Content Volume 11 No. 1 ∙ Feb 2018 1 Focus of the issue 2 30th Anniversary Events 3 School Events 4 Student Achievements 5 Research Centres 6 Staff Achievements Published by School of Law, CityU, Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon Tong Designed and printed by City University of Hong Kong Press Please send your comments to [email protected] ©2017 CityU School of Law. All rights reserved. Volume 11 No. 1 ∙ Feb 2018 3 FOCUS OF THE ISSUE Interviewing Dean Howells Blueprint for the School of Law Developing a world-class Q. As the leader of CityU Law School for three years now, could research profile you share with us your thoughts on the School’s strategic Q. How have your efforts for development in the years ahead? promoting active research among faculty been faring? A. We have a suite of programmes that work well for Hong Kong and the region. We may make strategic additions, but our main A. We are investing in our own goal is to increase the number of quality students taking our talent and attracting scholars courses. We also want to ensure our teaching is underpinned by from universities in the region quality research and investing in our research is a major priority. -

School of Law N E W S L E T T

Volume 13 No.2 JULY 2019 SCHOOL OF LAW NEWSLETTER School of Law City University of Hong Kong Contents CityU School of Law was established in 1987 with a mission to become an internationally-renowned centre for research and teaching of law in the INTERVIEWING DEAN Asia-Pacific region. Through cooperation with other law schools and 04 International outlook enhances appeal professional organizations, the School aims to foster an environment in which both students and staff develop and use their legal knowledge, professional SCHOOL OF LAW & CJER skills and expertise for the benefit of Hong Kong. Photo: istockphoto 06 (CENTRE FOR JUDICIAL EDUCATION AND RESEARCH) Programme enhances School of Law’s Our Programmes on offer: standing among the best in Asia Undergraduate and Taught Postgraduate Programmes ON COLLABORATIONS Bachelor of Laws (LLB) 08 CityU law students take great leap forward Juris Doctor (JD) Postgraduate Certificate in Laws (PCLL) Master of Laws (LLM) PROGRAMME HIGHLIGHTS Master of Laws in Arbitration and Dispute Resolution (LLMArbDR) 10 Hear what our Programme Directors say Professional Doctorate Programme Doctor of Juridical Science (JSD) ON MOOTING 16 Moot court contest victories put Research Degree Programmes CityU top for legal training Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Master of Philosophy (MPhil) RESEARCH CENTRES Recent activities and updates For further information, please contact us at 18 3442-8008 [email protected] STUDENT ACHIEVEMENTS Succeeding on all fronts School of Law School of Law 22 WeChat website STAFF ACHIEVEMENTS 26 Staff publications and presentations Published by School of Law, City University of Hong Kong, Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR. -

Report of the Subcommittee on Proposed Senior Judicial Appointments

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(4)1000/18-19 Ref : CB4/HS/1/18 Paper for the House Committee meeting on 21 June 2019 Report of the Subcommittee on Proposed Senior Judicial Appointments Purpose This paper reports on the deliberations of the Subcommittee on Proposed Senior Judicial Appointments ("the Subcommittee"). Background Constitutional and statutory provisions on senior judicial appointments 2. Article 48(6) of the Basic Law ("BL") confers on the Chief Executive ("CE") the power and function to appoint judges of the courts at all levels in accordance with legal procedures. In accordance with BL 88, judges shall be appointed by CE on the recommendation of an independent commission, namely, the Judicial Officers Recommendation Commission ("JORC"). JORC is established under section 3 of the Judicial Officers Recommendation Commission Ordinance (Cap. 92) ("the JORC Ordinance"). 3. In the case of the appointment of judges of the Court of Final Appeal ("CFA") and the Chief Judge of the High Court ("CJHC"), BL 90 provides that CE shall, in addition to following the procedures prescribed in BL 88, obtain the endorsement of the Legislative Council ("LegCo"). Subject to the endorsement of LegCo, CE shall report such appointment to the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress for the record. BL 73(7) correspondingly confers on LegCo the power and function to endorse the appointment of CFA judges and CJHC. 4. Pursuant to BL 88 and the JORC Ordinance, JORC is entrusted with the function of advising or making recommendations to CE regarding the filling of vacancies in judicial offices. -

Cacv 200/2008 in the High Court of the Hong Kong

CACV 200/2008 IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION COURT OF APPEAL CIVIL APPEAL NO. 200 OF 2008 (ON APPEAL FROM HCAP NO. 2 OF 2004) ____________ IN THE ESTATE OF MUI YIM FONG, deceased. ____________ BETWEEN TAM MEI KAM Plaintiff and HSBC INTERNATIONAL TRUSTEE 1st Defendant LIMITED (in the capacity as the sole executor and trustee named in the Purported Will of the Deceased dated 3rd December 2003) HSBC INTERNATIONAL TRUSTEE 2nd Defendant LIMITED (in the capacity as the Trustee of the Karen Trust, which is the sole devisee named in the Purported Will of the Deceased dated 3rd December 2003) NEW HORIZON BUDDHIST ASSOCIATION 3rd Defendant LIMITED LAU KAI EDDIE 4th Defendant ____________ Before: Hon Tang Ag CJHC, Yeung JA and Yuen JA in Court Date of Hearing: 19 August 2010 Date of Judgment: 7 October 2010 _______________ JUDGMENT _______________ Hon Tang Ag CJHC: 1. I have had the advantage of reading Yuen JA’s judgment in draft. With respect, I agree with it and have nothing to add. Hon. Yeung JA: 2. I agree with the judgment of Yuen JA and have nothing to add. Hon. Yuen JA: 3. In HCAP No.2 of 2004, the Plaintiff Madam Tam Mei Kam, the mother of the deceased, sought the following declarations, that: (1) the court pronounce against the validity of a Will in which the deceased appointed HSBC International Trustee Ltd her executor and trustee and bequeathed her entire estate to the Karen Trust; (2) a deed setting up the Karen Trust (of which HSBC International Trustee Ltd is also trustee) is void; and (3) the deceased died intestate. -

Acknowledgements.Pdf

Acknowledgements The following individuals and organisations are gratefully aclmowledged for providing information and/or photo(s) for the compilation this book (the Steering Committee apologises for unintended omissions): Individuals Cheung Wai-ping Francis Ho Suen-wai Annie Bentley Liang Ann-lee Linus Cheung Wing-lam Faith Ho Wat Chi-suk Au Fun-kuen Angela Cheung Wong Wan-yiu Gallant Ho Yiu-tai Amy Chan Cheng Yi-yim James Chiu Hui Yin-fat Francis Bong Shu-ying John Chiu Ip Shing-hing Vincent Chan Cheong-wa Chiu Ling-yang Jim Chi-yung Stephen Chan Chi-wan Yvonne Chiu Kam Hing-lam Christopher Chan Cheuk Anne Choi Ching-yee Tony Kan Chung-nin John Chan Cho-chak Andrew Choi Fook-ming Kan Lai-bing Chan Choi-lai Choi Sau-yuk Kan Yuet-keung Catherine Chan Ka-ki Catherine Chong Yuet-ngai Mary Kao May-loy Errol Chan Kam-kau Anna Chow Kiang Kwan-sang Chris Chan King-chi Selina Chow Liang Shuk-yee Vincent Ko Hon-chiu Daniel Chan Kwong-on Paul Chow Man-yiu Stanley Ko Kam-chuen Cecilia Chan Lai-wan Andrew Chow On-kin Ko Ping-keung Natalie Chan Man-se Chow Shew-ping Ko Tim-keung Chan Man-wai Nelson Chow Wing-sun Ko Tin-lung Mirrunie Michele Chan Mei-Ian Chow Yung-ping Norman Ko Wah-man Chan Nam Choy So-yuk Donald Koo Hoi-yan Chan Po-king Stanley Chu Yu-lun Kwan Chuk-fai Chan Siu-kam Chung Ling-hoi Edward Kwan Pak-churig Patrick Chan Siu-oi Chung Man-wing Vincent Kwan Pun-fong Thomas Chan Sze-tong Andrew Chung On-tak Susan Kwan Shuk-hing Alfred Chan Wing-kin Chung Pui-lam Simon Kwan Sin-ming Chan Wing-luk Timpson Chung Shui-ming Kenneth Kwok Hing-wai -

CA Orders Trial Judge to Convict Ex-General Manager of TVB and Company Director of Bribery and Impose Sentences

Hong Kong ICAC - Press Releases - CA orders trial judge to convict ex-general manager of TVB and company director of bribery and impose sentences CA orders trial judge to convict 26 October 2015 ex-general manager of TVB and company director of bribery and impose sentences The Court of Appeal (CA) today (Monday) ordered the District Court trial judge to convict a former general manager of Television Broadcasts Limited (TVB) and a then director of a production company of bribery and to hand down sentences in an ICAC case, after ruling that their earlier acquittals had no legal or factual basis. Stephen Chan Chi-wan, 56, former general manager of TVB, and Tseng Pei-kun, 33, then director of Idea Empire Advertising & Production Company Limited (IEAP), were acquitted at the District Court on September 2, 2011 after trial of five charges – three of bribery, two of which were alternative; and two of conspiracy to defraud. The Department of Justice (DoJ) subsequently filed an appeal with the CA against the acquittal of the three bribery charges by way of case stated, and the order of court costs granted by the trial judge to Chan and Tseng for their two acquitted charges of conspiracy to defraud. On November 21, 2012, the CA allowed the appeal by the DoJ, quashed the acquittals and remitted the case to the District Court for resumption of trial, but reserved its action to deal with the order of court costs. The trial judge, Poon Siu-tung, stood by his original verdict on March 7, 2013, hence Chan and Tseng were again acquitted of the three bribery charges. -

Brochure Template

Anti-Bribery and Corruption Review May 2016 Global contacts ...................................................... 3 World Map ............................................................... 4 s Foreword ................................................................. 6 t Europe, the Middle East and Africa ...................... 7 Belgium ............................................................... 8 Czech Republic ................................................... 9 n France ................................................................. 10 Germany .............................................................. 12 e Italy ...................................................................... 15 t Luxembourg ........................................................ 16 Poland ................................................................. 17 Romania .............................................................. 18 n Russia .................................................................. 20 Slovak Republic ................................................... 22 o Spain ................................................................... 24 The Netherlands .................................................. 25 c Turkey .................................................................. 28 Ukraine ................................................................ 29 United Arab Emirates ........................................... 30 United Kingdom ................................................... 31 The Americas ......................................................... -

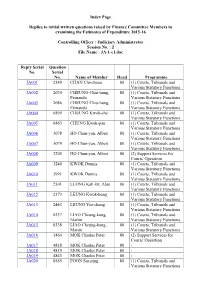

Judiciary Administrator Session No

Index Page Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2015-16 Controlling Officer : Judiciary Administrator Session No. : 2 File Name : JA-1-e1.doc Reply Serial Question No. Serial No. Name of Member Head Programme JA001 2349 CHAN Chi-chuen 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA002 2074 CHEUNG Chiu-hung, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Fernando Various Statutory Functions JA003 2086 CHEUNG Chiu-hung, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Fernando Various Statutory Functions JA004 6899 CHEUNG Kwok-che 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA005 0463 CHUNG Kwok-pan 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA006 3078 HO Chun-yan, Albert 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA007 3079 HO Chun-yan, Albert 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA008 3205 HO Chun-yan, Albert 80 (2) Support Services for Courts' Operation JA009 3246 KWOK Dennis 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA010 3991 KWOK Dennis 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA011 2501 LEONG Kah-kit, Alan 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA012 2173 LEUNG Kwok-hung 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA013 2443 LEUNG Yiu-chung 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA014 0337 LIAO Cheung-kong, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Martin Various Statutory Functions JA015 0338 LIAO Cheung-kong, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Martin Various Statutory Functions JA016 1464 MOK Charles Peter 80 (2) Support Services for Courts' Operation JA017 4818 MOK Charles Peter 80 - JA018 4819 MOK Charles Peter 80 - JA019 4843 MOK Charles Peter 80 - JA020 0555 POON Siu-ping 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions Reply Serial Question No. -

National Judges College and City University of Hong Kong Successfully Held Symposium

National Judges College and City University of Hong Kong Successfully Held Symposium 20th December 2019 Wong Yu Hing City University of Hong Kong has collaborated with the Supreme People’s Court of the People’s Republic of China and its National Judges College since 2009. Together they have organized a number of programmes for Chinese senior judges and have educated elites in the field. To celebrate 10-year cooperation between National Judges College and City University of Hong Kong (CityU), a Symposium and Case Law and Case Guidance System Forum were held on 8 December 2019 at National Judges College in Beijing. The symposium aims to summarize and review the achievements of the project since the implementation of the project for ten years, to discuss the guiding system of case with Chinese characteristics, and to further strengthen judicial exchanges and cooperation between the two places. Representatives of the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office of the State Council, the Supreme People's Court, some local courts, the Case Law Research Society of the Chinese Law Society, the Hong Kong High Court, the Law Society of Hong Kong, experts and scholars from Peking University, the University of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the National Judges College, the City University of Hong Kong, and representatives of teachers and students of the cooperative project participated in the meeting. The officiating guests included YANG Wanming, Vice President of the Supreme People's Court, HU Yunteng. Grand Justice of the Supreme People's Court; Justice Wally YEUNG Chun-kuen, Vice President of the Court of Appeal of the High Court; JIANG Huiling, Senior Judge and Vice President of the National Judges College; Mr.