April 06 WEB Prog.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Debut Concert

PERFORMERS Timothy Steeves, violin Dian Zhang, violin Jarita Ng, viola Jakob Nierenz, cello Austin Lewellen, double bass Christina Hughes, flute and piccolo DEBUT CONCERT Katie Hart, oboe and english horn Thomas Frey, clarinet and bass clarinet Ben Roidl-Ward, bassoon and contrabassoon Michael Chen, trumpet (Mazzoli only) Daniel Egan, trumpet Daniel Hawkins, horn Tanner Antonetti, trombone Craig Hauschildt, percussion (Norman and Cerrone) Brandon Bell, percussion (Norman and Adès) Yvonne Chen,! piano Tuesday, December 6, 2016 Led by conductor, Jerry Hou 7:30pm ! SPECIAL THANKS TO Gallery at MATCH Ally Smither, Loop38 singer and staff Ling Ling Huang, Loop38 violinist and staff 3400 Main Street Fran Schmidt, recording Brian Hodge, Anthony Brandt, and Chloe Jolly, Musiqa Houston, TX 77002 Scuffed Shoe ! Lynn Lane Photography ! ! MORE INFO AT ! WWW.LOOP38.ORG new music in the heart of Houston www.loop38.org /Loop38 /instaloop38 /Loop38music PROGRAM Living Toys (1993) Thomas Adès (b.1971) Try (2011) Andrew Norman (b.1979) 18 min. 14 min. I. Angels Winner of the 2016 Grawemeyer Award, Andrew Norman is a Los Angeles- II. Aurochs based composer whose work draws on an eclectic mix of sounds and -BALETT- notational practices from both the avant-garde and classical traditions. He is III. Militiamen increasingly interested in story-telling in music, specifically in the ways non- linear, narrative-scrambling techniques from other time-based media like movies IV. H.A.L.’s Death and video games might intersect with traditional symphonic forms. -BATTLE- V. Playing Funerals Recovering (2011/12) Christopher Cerrone (b.1984) -TABLET- 8 min. “When the men asked him what he wanted to be, the child did not name any of Brooklyn-based composer Christopher Cerrone is internationally acclaimed for their own occupations, as they had all hoped he would, but replied: ‘I am going music which ranges from opera to orchestral, from chamber music to electronic. -

Guest Artist:Marilyn Nonken, Piano "Signature Pieces"

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 10-16-2002 Guest Artist:Marilyn Nonken, Piano "Signature Pieces" Marilyn Nonken Piano Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Nonken, Marilyn Piano, "Guest Artist:Marilyn Nonken, Piano "Signature Pieces"" (2002). School of Music Programs. 2355. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/2355 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I llinois S-\;crte Univel'si-\;4 -School of Music I I I G ued:: Artist I Mcrr>ilyn Nonken, piano I " I "S. ig natu,-,e Pieces I I I I I Cent..,. fa,, the P.,,fcrrmm~ / ',r•' I 'W ed neda~ {;;;vonir.9 Octob..,.· 16, '200'2 8 :00 p.m. I The t;ighteenth P"°91""'m of the '200'2-'2003 S9Gl<on . P-roqram I I David Rakowski studied at New England Conservatory, Princeton, and Tanglewood with Milton Babbitt, Sliding Scales David Rakowskil I Luciano Berio, Peter Westergaard, Paul Lansky, and Robert Ceely. He has received plenty of awards and 12-Step Program (2002) commissions, is published by C.F. Peters, and was twice a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Music: in 1999 for Persistent Memory, commissioned and premiered by the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra; and in 2002 for Ten of a Kind, commissioned and premiered by "The President's Own" U.S. -

T H E P Ro G

Sunday, December 3, 2017, at 11:00 am m a Sunday Morning Coffee Concerts r g o r Conrad Tao, Piano P BACH Chromatic fantasia and fugue in D minor (c. 1720) e h JASON ECKARDT Echoes’ White Veil (1996) T RACHMANINOFF Étude-tableau in A minor (191 6–17) BEETHOVEN Sonata No. 31 in A-flat major (1821 –22) Moderato cantabile, molto espressivo Allegro molto Adagio, ma non troppo—Fuga: Allegro, ma non troppo This program is approximately one hour long and will be performed without intermission. Please join the artist for a cup of coffee following the performance. Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. Refreshments provided by Zabar’s and zabars.com This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Steinway Piano Walter Reade Theater Great Performers Support is provided by Rita E. and Gustave M. Hauser, Audrey Love Charitable Foundation, Great Performers Circle, Chairman’s Council, and Friends of Lincoln Center. Public support is provided by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. Endowment support for Symphonic Masters is provided by the Leon Levy Fund. Endowment support is also provided by UBS. American Airlines is the Official Airline of Lincoln Center Nespresso is the Official Coffee of Lincoln Center NewYork-Presbyterian is the Official Hospital of Lincoln Center UPCOMING GREAT PERFORMERS EVENTS: Wednesday, December 6 at 7:30 pm in Alice Tully Hall Bach Collegium Japan Masaaki Suzuki, conductor Sherezade Panthaki, soprano Jay Carter, countertenor Zachary Wilder, tenor Dominik Wörner, bass BACH: Four Cantatas from Weihnachts-Oratorium (“Christmas Oratorio”) Pre-concert lecture by Michael Marissen at 6:15 pm in the Stanley H. -

The Heraclitian Form of Thomas Adès's Tevot As a Critical Lens

The Art of Transformation: The Heraclitian Form of Thomas Adès’sTevot as a Critical Lens for the Symphonic Tradition and an original composition, Glimmer, Glisten, Glow for sinfonietta A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Music Composition and Theory David Rakowski and Yu-Hui Chang, Advisors In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Joseph Sowa May 2019 The signed version of this form is on file in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. This dissertation, directed and approved by Joseph Sowa’s Committee, has been accepted and approved by the Faculty of Brandeis University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Eric Chasalow, Dean Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Dissertation Committee: David Rakowski, Brandeis University Department of Music Yu-Hui Chang, Brandeis University Department of Music Erin Gee, Brandeis University Department of Music Martin Brody, Wellesley College, Department of Music iii Copyright by Joseph Sowa 2019 Acknowledgements The story of my time at Brandeis begins in 2012, a few months after being rejected from every doctoral program to which I applied. Still living in Provo, Utah, I picked up David Ra- kowski from the airport for a visit to BYU. We had met a few years earlier through the Barlow Endowment for Music Composition, when Davy was on the board of advisors and I was an intern. On that drive several years later, I asked him if he had any suggestions for my doc- toral application portfolio, to which he immediately responded, “You were actually a finalist.” Because of his encouragement, I applied to Brandeis a second time, and the rest is history. -

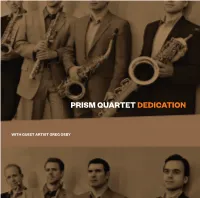

Prism Quartet Dedication

PRISM QUARTET DEDICATION WITH GUEST ARTIST GREG OSBY PRISM Quartet Dedication 1 Roshanne Etezady Inkling 1:09 2 Zack Browning Howler Back 1:09 3 Tim Ries Lu 2:36 4 Gregory Wanamaker speed metal organum blues 1:14 5 Renée Favand-See isolation 1:07 6 Libby Larsen Wait a Minute... 1:09 7 Nick Didkovksy Talea (hoping to somehow “know”) 1:06 8 Nick Didkovksy Stink Up! (PolyPrism 1) 1:06 9 Nick Didkovksy Stink Up! (PolyPrism 2) 1:01 10 Greg Osby Prism #1 (Refraction) 6:49 Greg Osby, alto sax solo 11 Donnacha Dennehy Mild, Medium-Lasting, Artificial Happiness 1:49 12 Ken Ueno July 23, from sunrise to sunset, the summer of the S.E.P.S.A. bus rides destra e sinistra around Ischia just to get tomorrow’s scatolame 1:20 13 Adam B. Silverman Just a Minute, Chopin 2:21 14 William Bolcom Scherzino 1:16 Matthew Levy Three Miniatures 15 Diary 2:05 16 Meditation 1:49 17 Song without Words 2:33 PRISM Quartet/Music From China 3 18 Jennifer Higdon Bop 1:09 19 Dennis DeSantis Hive Mind 1:06 20 Robert Capanna Moment of Refraction 1:04 21 Keith Moore OneTwenty 1:31 22 Jason Eckardt A Fractured Silence 1:18 Frank J. Oteri Fair and Balanced? 23 Remaining Neutral 1:00 24 Seeming Partial 3:09 25 Uncommon Ground 1:00 26 Incremental Change 1:49 27 Perry Goldstein Out of Bounds 1:24 28 Tim Berne Brokelyn 0:57 29 Chen Yi Happy Birthday to PRISM 1:24 30 James Primosch Straight Up 1:24 31 Greg Osby Prism #1 (Refraction) (alternate take) 6:49 Greg Osby, alto sax solo TOTAL PLAYING TIME 57:53 All works composed and premiered in 2004 except Three Miniatures, composed/premiered in 2006. -

The Music of Pierre Jalbert

" an acknowledged chamber-music master." – THE NEW YORKER American composer Pierre Jalbert has been recognized for his richly colored and superbly crafted scores and “music of fierce and delicate inventiveness [with] kaleidoscope of moods and effects.” (Cleveland Plain Dealer) Painting vibrant and picturesque sonic portraits for the listener, he has developed a musical language that is engaging, expressive, and deeply personal. Among his many honors are the Rome Prize, BBC Masterprize, Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center's Stoeger Award, given biennially "in recognition of significant contributions to the chamber music repertory," and an award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Jalbert’s work has drawn inspiration from a variety of sources ranging from plainchant melodies to natural phenomena, and his French-Canadian heritage, hearing English folk songs and Catholic liturgical music growing up. He has earned a reputation for his mastery of color, in both his chamber and orchestral scores, creating timbres that are vivid yet refined and tonally centered, combining modal, tonal, and dissonant sonorities as it travels new and unusual paths, while retaining a sense of harmonic motion culminating in a completed journey. His music has been commissioned and performed worldwide, including the St. Paul and Los Angeles Chamber orchestras, the American Composers Orchestra, and the Symphonies of Houston, Vermont, Albany, Budapest, London, Boston and Milwaukee, the National Symphony, Cabrillo and Eastern Festival Orchestras. He received two Meet the Composer grants, including one for its “Magnum Opus Project.” Jalbert served as Composer-in-Residence with the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, California Symphony and Chicago's Music in the Loft. -

Agnieszka Roginska

1 Marilyn Nonken New York University, Steinhardt School Music and Performing Arts, Piano Studies 35 West Fourth Street, New York, NY 10012 (212) 998-5612 [email protected] http://steinhardt.nyu.edu/music/faculty/Marilyn_Nonken http://marilynnonken.com HIGHLIGHTS Recordings 25+ recordings as soloist, duo pianist, chamber musician. Publications Two monographs, 20+ journal articles, book chapters, invited publications. Performances 25+ years performing at major international venues. Expertise Piano performance, musicology, theory, post-1945 music, ecological psychology, aesthetics, performance practice, identity/diversity/equity/access in the arts. Leadership Director of Piano Studies, 15+ years administration and direction of non-profit performing, commissioning and presenting arts organizations. EDUCATION 1999 PhD, Musicology/Theory. Columbia University, New York. Dissertation: An Ecological Approach to Music Perception: Stimulus-Driven Listening and the Complexity Repertoire. Advisor: Fred Lerdahl. 1995 MPhil, Musicology/Theory. Columbia University, New York. 1995 MA, Musicology/Theory. Columbia University, New York. 1992 Zertifikat, Internationalen Meisterkurs für Interpretation Neuer Klaviermusik, Musikakademie Rheinsberg, Germany. Mentor: Leonard Stein. 1992 BMus, Theory. Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester, New York. Mentor: David Burge. ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2013-2019 Associate Professor. Steinhardt School, New York University, New York. 2006–2013 Assistant Professor. Steinhardt School, New York University, New York. 2005–2006 Adjunct Professor. Department of Music, Columbia University, New York. 1994–1996 Instructor. Department of Music, Columbia University, New York. MONOGRAPHS Nonken, Marilyn. Identity and Diversity in New Music: The New Complexities. Routledge, 2019. Nonken, Marilyn. The Spectral Piano: From Liszt, Scriabin, and Debussy to the Digital Age. Cambridge University Press, 2014. Paperback edition, 2016. 2 BOOK CHAPTERS AND EDITED VOLUMES Nonken, Marilyn. -

Calder Quartet

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Sunday, October 2, 2011, 3pm Franz Liszt (1811–1886) Petrarch Sonnet No. 123 (I’ vidi in terra angelici Hertz Hall costumi) from Années de Pèlerinage, Deuxième Année: Italie for Piano (1845) Calder Quartet Adès The Four Quarters for String Quartet (2010) Nightfalls Benjamin Jacobson violin Serenade: Morning Dew Andrew Bulbrook violin Days Jonathan Moerschel viola The Twenty-fifth Hour Eric Byers cello with Adès Quintet for Piano and String Quartet, Thomas Adès, piano Op. 20 (2000) PROGRAM Cal Performances’ 2011–2012 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Three Pieces for String Quartet (1914) Dance: Quarter note = 126 Eccentric: Quarter note = 76 Canticle: Half note = 40 Thomas Adès (b. 1971) Mazurkas for Piano, Op. 27 (2009) Moderato, molto rubato Prestissimo molto espressivo Grave, maestoso Adès Arcadiana for String Quartet (1994) Venezia notturna Das klinget so herrlich, das klinget so schön Auf dem Wasser zu singen Et... (tango mortale) L’Embarquement O Albion Lethe INTERMISSION 6 CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES 7 PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) music at the time. He later explained the move- prominence—the piano solos Still Sorrowing American premiere at Santa Fe Opera in July Three Pieces for String Quartet ment’s inspiration in an interview with Robert and Darknesse Visible, the song cycles Five Eliot 2006 and has been announced for the 2012– Craft: “I had been fascinated by the movements Landscapes and Life Story, Catch and Living Toys 2013 Metropolitan Opera season. Composed in 1914. Premiered on November 8, of Little Tich, whom I had seen in London in for chamber orchestra—and in 1993 he was ap- The distinguished critic Andrew Porter 1915, in Chicago by the Flonzaley Quartet. -

Saturday 14 March 2020 West Road Concert Hall, Cambridge C-Phil-23-May-20-A5-V2 18/02/2020 17:01 Page 1

Saturday 14 March 2020 West Road Concert Hall, Cambridge c-phil-23-may-20-A5-v2 18/02/2020 17:01 Page 1 Saturday 23 May 2020 at 7.30pm West Road Concert Hall, Cambridge TheFamily concert poster Bells Rachmaninov The Bells Three Russian Songs Mussorgsky arr. Shostakovich Songs & Dances of Death Bartók Dance Suite Conductor Timothy Redmond Soprano Anna Gorbachyova Tenor Alexander James Edwards Bass-baritone Vassily Savenko Cambridge Philharmonic Orchestra & Chorus All tickets (reserved): £12, £16, £20, £25 (Students and under-18s £10 on the door) Box Office: 0333 666 3366 (TicketSource) Online: www.cambridgephilharmonic.com Cambridge Philharmonic presents Beethoven Leonore Overture No. 3 Elegischer Gesang Choral Fantasia Interval Mozart Piano Concerto in A K488 ‘Coronation’ Mass in C K317 Cambridge Philharmonic Orchestra & Chorus Timothy Redmond: Conductor Tom Primrose: Conductor Elegischer Gesang Paula Muldoon: Leader Florian Mitrea Piano Helena Moore Soprano Julia Portela Piñón Mezzo soprano Aaron Godfrey Mayes Tenor Michael Ronan Baritone Cambridge Philharmonic gratefully acknowledges the support of the Josephine Baker Trust towards the cost of tonight’s solo singers Leonore Overture No. 3, Op. 72 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Background The three ‘Leonore’ overtures were written for the early versions of Beethoven’s opera Fidelio, but were later discarded in favour of a new overture, composed as part of the final version of the opera premiered in 1814. Chronologically, the first of the Leonore overtures is No. 2, composed for a production in Vienna in 1805. The opera was not particularly well received, and Beethoven made extensive revisions in time for a further production in the spring of 1806, and added a revised overture, Leonore No. -

Wind Symphony and Wind Ensemble with Guest Composer, Geoffrey Gordon

KENNESAW STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC Wind Symphony DEBRA TRAFICANTE CONDUCTOR and Wind Ensemble DAVID T. KEHLER MUSIC DIRECTOR AND CONDUCTOR with Guest Composer Geoffrey Gordon Monday, November 14, 2016 at 8 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall Thirty-ninth Concert of the 2016-17 Concert Season program KSU WIND SYMPHONY MICHAEL DAUGHERTY (b. 1954) Desi (1991) IRA HEARSHEN (b. 1948) Symphony on Themes of John Phillip Sousa II. After the Thunderer (1994) JOHN BARNES CHANCE (1932-1972) Variations on a Korean Folk Song (1965) JOHN MACKEY (b. 1973) Kingfisher’s Catch Fire (2007) intermission KSU WIND ENSEMBLE NIKOLAI RIMSKY-KORSAKOV (1844-1908) Procession of the Nobles (1870/1938) (celebrating KSU’s Year of Russia) GEOFFREY GORDON (b. 1968) ROCKS (2016) *World Premiere I. Obsidian II. Slate III. Blue Lapis IV. Amethyst V. Sulfur ALFRED REED (1921-2005) Russian Christmas Music (1944) (celebrating KSU’s Year of Russia) program notes Desi | Michael Daughtery Michael Daugherty was born into a musical family on April 28, 1954, in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. His father Willis Daugherty (1929-2011) was a jazz and country and western drummer, his mother Evelyn Daugherty (1927-1974) was an amateur singer, and his grandmother Josephine Daugherty (1907- 1991) was a pianist for silent film. As a GRAMMY® award-winning composer, Michael Daugherty is one of the most commissioned, performed, and recorded composers on the American concert music scene today. Daugherty first came to international attention when the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, conducted by David Zinman, performed his Metropolis Symphony at Carnegie Hall in 1994. Since that time, Daugherty’s music has entered the orchestral, band and chamber music repertory and made him, according to the League of American Orchestras, one of the ten most performed American composers. -

Adès: Asyla, Tevot, Polaris, Brahms

Thomas Adès (b 1971) Page Index Asyla, Op 17 (1997) Tevot (2005–6) 3 Programme Notes 6 Notes de programme Polaris [Voyage for Orchestra] (2010) 9 Einführungstexte Brahms (2001) 12 Sung text Thomas Adès conductor 13 Composer / conductor biography London Symphony Orchestra 16 Soloist biography 18 Orchestra personnel lists (1997) Asyla, Op 17 22 LSO biography / Also available on LSO Live 1 I. 5’50’’ 2 II. 6’34’’ 3 III. Ecstasio 6’35’’ 4 IV. Quasi leggiero 5’02’’ 5 Tevot (2005–6) 20’19’’ 6 Polaris [Voyage for Orchestra] (2010) 13’30’’ 7 Brahms, Op 21 (2001) 5’05’’ Total time 62’55’’ Recorded live in DSD 128fs, 9 March (Tevot, Polaris, Brahms) & 16 March (Asyla) 2016, at the Barbican, London James Mallinson producer Classic Sound Ltd recording, editing and mastering facilities Jonathan Stokes for Classic Sound Ltd balance engineer, audio editor, mixing and mastering engineer Neil Hutchinson for Classic Sound Ltd recording engineer Booklet notes / Notes de programme / Einführungstexte © Paul Griffiths Translation into French / Traduction en français – Claire Delamarche Translation into German / Übersetzung aus dem Englischen – Elke Hockings © 2016 London Symphony Orchestra, London UK P 2016 London Symphony Orchestra, London UK 2 Programme Notes Next comes a slow movement, whose descents upon descents are begun by Thomas Adès (b 1971) keyed instruments and soon spread through the orchestra, led at first by bass Asyla, Op 17 (1997) oboe. There may be the sense of lament, or chant, echoing in some vast space – though a central section is more agitated and dynamic. There follows the club Asyla are places of safety. -

Living Toys I Angels Thomas Adès

THOMAS ABÉ FABER TT MUSIC © 1996 by Faber Music Ltd First published in 1996 by Faber Music Ltd 3 Queen Square London WC1N 3AU Amended impression June 1997 Music processed by Donald Sheppard Cover Drawing: The agility and daring of Juanito Apinani in the bullring at Madrid by Goya Cover design by S & M Tucker Printed in England by Hobbs the Printers, Southampton All rights reserved ISBN 0 571 51706 4 To buy Faber Music publications or to find out about the full range of titles available please contact your local music retailer or Faber Music sales enquiries: Tel: +44 (0) 171 833 7931 Fax: +44 (0) 171 278 3817 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.fabermusic.co.uk Permission to perform this work in public must be obtained from the Society duly controlling performing rights unless there is a current licence for public performance from the Society in force in relation to the premises at which the performance is to take place. Such permission must be obtained in the UK and Eire from Performing Right Society Ltd, 29-33 Berners Street, London W1P4AA Commissioned by the Arts Council of Great Britain for the London Sinfonietta The first performance was given by the London Sinfonietta conducted by Oliver Knussen in the Barbican Hall, London, on 11 February 1994 Duration: 17 minutes INSTRUMENTATION flute = piccolo = oboe cor anglais + sopranino recorder clarinet in Bl> = El> clarinet + bass clarinet bassoon = contrabassoon horn = whip = trumpet in B\> piccolo trumpet in Bl> trombone percussion (1 player) 3 gongs , 2 large pedal timpani 2 crotales (with bow), talking drum, triangle, 2 suspended cymbals: small and very small, suspended sheet of paper (A3 to A4, struck centrally with side drum beater*), 2 cowbells: medium high and very high, 2 temple blocks: medium and high, guero, castanets, piccolo snare drum, field drum (deep, with snares), kit bass drum, vibraslap.