Two Poems on the Death of the Duke of Lennox and Richmond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

The Chiefs of Colquhoun and Their Country, Vol. 1

Ë D IMBUR6H I 8 6 9. THE CHIEFS OF COLQUHOUN AND THEIR COUNTRY. Impression: One Hundred and Fifty Copies, In Two Volumes. PRINTED FOR SIR JAMES COLQUHOUN OF COLQUHOUN AND LUSS, BARONET. No. /4 ?; ^ Presented to V PREFACE. AMONG the baronial families of Scotland, the chiefs of the Clan Colquhoun occupy a prominent place from their ancient lineage, their matrimonial alliances, historical associations, and the extent of their territories in the Western Highlands. These territories now include a great portion of the county of Dumbarton. Upwards of seven centuries have elapsed since Maldouen of Luss obtained from Alwyn Earl of Lennox a grant of the lands of Luss; and it is upwards of six hundred years since another Earl of Lennox granted the lands of Colquhoun to Humphrey of Kil- patrick, who afterwards assumed the name of Colquhoun. The lands and barony of Luss have never been alienated since the early grant of Alwyn Earl of Lennox. For six generations these lands were inherited by the family of Luss in the male line; and in the seventh they became the inheritance of the daughter of Godfrey of Luss, commonly designated " The Fair Maid of Luss," and, as the heiress of these lands, she vested them by her marriage, about the year 1385, in her husband, Sir Eobert Colquhoun of Colquhoun. The descendant from that marriage, and the repre sentative of the families of Colquhoun and Luss, is the present baronet, Sir James Colquhoun. The lands and barony of Colquhoun also descended in the male line of the family of Colquhoun for nearly five centuries; and although the greater part of them has been sold, portions still a VI PREFACE. -

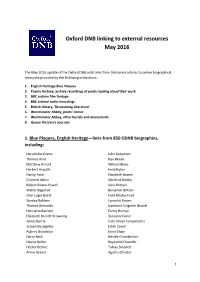

Oxford DNB Linking to External Resources May 2016

Oxford DNB linking to external resources May 2016 The May 2016 update of the Oxford DNB adds links from Dictionary articles to online biographical resources provided by the following institutions: 1. English Heritage Blue Plaques 2. Poetry Archive, archive recordings of poets reading aloud their work 3. BBC archive film footage 4. BBC archive radio recordings 5. British Library, ‘Discovering Literature’ 6. Westminster Abbey, poets’ corner 7. Westminster Abbey, other burials and monuments 8. Queen Victoria’s Journals 1. Blue Plaques, English Heritage—links from 850 ODNB biographies, including: Harold Abrahams John Betjeman Thomas Arne Nye Bevan Matthew Arnold William Blake Herbert Asquith Enid Blyton Nancy Astor Elizabeth Bowen Clement Attlee Winifred Holtby Robert Paden-Powell Vera Brittain Walter Bagehot Benjamin Britten John Logie Baird Ford Madox Ford Stanley Baldwin Lancelot Brown Thomas Barnardo Isambard Kingdom Brunel Henrietta Barnett Fanny Burney Elizabeth Barrett Browning Giovanni Canal James Barrie Cato Street Conspirators Joseph Bazalgette Edith Cavell Aubrey Beardsley Ernst Chain Harry Beck Neville Chamberlain Hilaire Belloc Raymond Chandler Hector Berlioz Tobias Smollett Annie Besant Agatha Christie 1 Winston Churchill Arthur Conan Doyle William Wilberforce John Constable Wells Coates Learie Constantine Wilkie Collins Noel Coward Ivy Compton-Burnett Thomas Daniel Charles Darwin Mohammed Jinnah Francisco de Miranda Amy Johnson Thomas de Quincey Celia Johnson Daniel Defoe Samuel Johnson Frederic Delius James Joyce Charles Dickens -

17Th Century Gaming Counter of Charles Lennox, Duke of Richmond, Illegitimate Son of King Charles II of SOLD England

17th century gaming counter of Charles Lennox, Duke of Richmond, illegitimate son of King Charles II of SOLD England REF:- 140993 Diameter: 1 cm (0 1/2") 1 Sanda Lipton Antique Silver Suite 202, 2 Lansdowne Row, Berkeley Square, London W1J 6HL +44 (0) 20 7431 2688 https://antique-silver.com/17th-century-gaming-counter-of-charles-lennox-duke-of 29/09/2021 Short Description Very striking silver, octagonal, 17th century gaming counter belonging to Charles Lennox, Duke of Richmond (1672 - 1723). He was the illegitimate son of King Charles II of England and his mistress, French Breton noblewoman Louise de Penancoet de Kerouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth. Obverse:- The full coat of arms of Charles Lennox, within a royal mantle. Ducal coronet with royal lion above. On a riband below, the Lennox motto:- EN LA ROSE JE FLEURI (I flourish in the rose). Reverse:- Charles Lennoxs very intricate monogram within a mantle with ducal coronet above. 1675 - Created Duke of Richmond, Earl of March and Baron Settrington in the Peerage of England. Also, Duke of Lennox, Earl of Darnley and Lord Torbolton in the Peerage of Scotland. 1681 - Invested as a Knight of the Garter. Appointed Lord High Admiral for life but this was only effective between 1701 and 1705 when Lennox resigned all his Scottish lands and offices. 1696 - Master of a masonic Lodge in Chichester - one of the few known Freemasons in the 17th century. He married Lady Anne Brudenell, daughter of Lord Brudenell and granddaughter of the Earl of Cardigan in 1692. The Duke loved hunting and gambling. -

The Signatories: Lennox

The signatories: Lennox Ludovic Stuart (1574-1624), 2nd Duke of Lennox, was born into the “Auld Alliance” between Scotland and France and came to maturity in the “new alliance” between Scotland and England. Ludovic was the son of Esmé Stuart, 6th Seigneur d’Aubigny. Esmé was first cousin to Henry Stuart Lord Darnley, the unfortunate husband of Mary Queen of Scots and father of King James VI of Scotland and I of England. (For those who like to trace lines of descent: Ludovic’s grandfather was John Stuart, 5th Seigneur d’Aubigny, brother to Matthew Stuart, 4th Earl of Lennox, father of Darnley and therefore James VI & I’s grandfather.) It was not unusual for prominent Scottish families to have ties to both Scotland and France. This was a direct result of the “Auld Alliance.” The “Auld Alliance” was based on a need, shared by Scotland and France, to contain English expansion. A long-standing connection, it was formally established by treaty in 1295, renewed by Robert the Bruce in 1326, and cemented by Scottish King James I (1394-1437) who sent Scottish forces to fight for the French King Charles VII (and Joan of Arc) against the English. During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries the countries assisted each other against the English on several occasions. The “Auld Alliance” was primarily a military and diplomatic alliance but there were cultural associations as well, with French influence being felt in Scottish architecture and law. One significant aspect of the "Auld Alliance" was the existence of French titles and lands held by Scots nobles. -

Court: Women at Court, and the Royal Household (100

Court: Women at Court; Royal Household. p.1: Women at Court. Royal Household: p.56: Gentlemen and Grooms of the Privy Chamber; p.59: Gentlemen Ushers. p.60: Cofferer and Controller of the Household. p.61: Privy Purse and Privy Seal: selected payments. p.62: Treasurer of the Chamber: selected payments; p.63: payments, 1582. p.64: Allusions to the Queen’s family: King Henry VIII; Queen Anne Boleyn; King Edward VI; Queen Mary Tudor; Elizabeth prior to her Accession. Royal Household Orders. p.66: 1576 July (I): Remembrance of charges. p.67: 1576 July (II): Reformations to be had for diminishing expenses. p.68: 1577 April: Articles for diminishing expenses. p.69: 1583 Dec 7: Remembrances concerning household causes. p.70: 1598: Orders for the Queen’s Almoners. 1598: Orders for the Queen’s Porters. p.71: 1599: Orders for supplying French wines to the Royal Household. p.72: 1600: Thomas Wilson: ‘The Queen’s Expenses’. p.74: Marriages: indexes; miscellaneous references. p.81: Godchildren: indexes; miscellaneous references. p.92: Deaths: chronological list. p.100: Funerals. Women at Court. Ladies and Gentlewomen of the Bedchamber and the Privy Chamber. Maids of Honour, Mothers of the Maids; also relatives and friends of the Queen not otherwise included, and other women prominent in the reign. Close friends of the Queen: Katherine Astley; Dorothy Broadbelt; Lady Cobham; Anne, Lady Hunsdon; Countess of Huntingdon; Countess of Kildare; Lady Knollys; Lady Leighton; Countess of Lincoln; Lady Norris; Elizabeth and Helena, Marchionesses of Northampton; Countess of Nottingham; Blanche Parry; Katherine, Countess of Pembroke; Mary Radcliffe; Lady Scudamore; Lady Mary Sidney; Lady Stafford; Countess of Sussex; Countess of Warwick. -

Inheritance, War and Antiquarianism: Sir Alan Stewart of Darnley, 2Nd Seigneur D'aubigny Et De Concressault 1429–371

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 143 (2013), 339–361 INHERITANCE, WAR AND ANTIQUARIANISM | 339 Inheritance, war and antiquarianism: Sir Alan Stewart of Darnley, 2nd seigneur d’Aubigny et de Concressault 1429–371 Elizabeth Bonner* ABSTRACT This article concerns the establishment in France of the Lennox-Stuart/Stewarts2 of Darnley at the height of the Hundred Years’ War in the 1420s. In time, they were to become possibly the single most important family involved in the politics and diplomacy of the monarchies and government in the kingdoms of Scotland, France and England during the entire 15th and 16th centuries. This research also concerns a re-evaluation of the works of those 18th- and 19th-century antiquarians who have been the principal authors of this family’s Histories, by verifying their interpretations of sources, in particular their manuscript sources in the archives and libraries of all three ancient kingdoms.3 This is in line with recent reviews of the works of antiquarians of all eras; but the works of the 18th-century antiquarians have been of particular interest.4 Thus, the history of this family has relied, up until now, entirely on the works of antiquarians which, due to general pejorative views of their publications, have suffered a seeming distrust by modern professional historians. Finally, recent research into the private Stuart archives at the Château de La Verrerie demonstrates the rationale and legal mechanisms by which Charles VII intervened in 1437 regarding the inheritance of Sir Alan Stewart of Darnley’s seigneuries d’Aubigny et de Concressault by his brother John. This document is important, as it set a precedence for later legal inheritance and transfer of the titles of the seigneuries in the family, and ultimately to transferring the lands and title to the Scottish Lennox- Stuarts/Stewarts and their descendants in the 16th century. -

Ham House the Green Closet Miniatures and Cabinet Pictures Ham House the Green Closet Miniatures and Cabinet Pictures a HISTORIC HANG REVIVED

Ham House The Green Closet miniatures and cabinet pictures Ham House The Green Closet miniatures and cabinet pictures A HISTORIC HANG REVIVED The collection of miniatures at Ham House is one of the largest accumulations of miniatures by one family to have remained substantially intact. Its display with small paintings and other images in an early 17th-century picture closet is without surviving parallel in England. By 1990, however, almost all the pictures and miniatures were displayed elsewhere, and the original purpose of the Green Closet was no longer evident. The substantial restoration of the historic groupings on its walls, with the kind agreement of the Victoria & Albert Museum, has revived the spirit, and much of the appearance, of the traditional arrangement. Designed to display both cabinet fring’d’ hanging from ‘guilt Curtaine rods dismantled) that extended even to the pictures and miniatures on an intimate round the roome’,which could be drawn sides of the chimneybreast. This was the scale, in contrast to the arrays of three- to protect the paintings from light and arrangement in 1844, when 97 pictures quarter-length portraits in the adjoining dust. The table and green-upholstered were listed, a considerable increase on Long Gallery, the Green Closet is of the seat furniture were also provided with 1677, when there were 57, but the spirit greatest rarity, not only as – in its core – sarsenet case-covers. Modern copies of all of the 17th-century room was a survival from the reign of Charles I these decorative and practical furnishings undoubtedly preserved. It may be that (whose own closets for the display of and fittings have recently been provided. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigeui Copyri^T By

This dissertation has been 63—6782 microfilmed exactly as received SCOUFOS, Alice Lyle, 1921- SHAKESPEARE AND THE LORDS OF COBHAM. The Ifoiversity of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1963 Language and Literature, modem University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigeui Copyri^t by Alice Lyle Scoufos 1963 THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE SHAKESPEARE AND THE LORDS OF COBHAM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the d e g re e of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ALICE LYLE SCOUFOS Norman, Oklahoma 1963 SHAKESPEARE AND THE LORDS OF COBHAM APPROVED BY (• 'è ' ' m 0^ . ^ 44— W • II Hj------------------ u. ^vuAiL y DISSERTATION COMMITTEE TABLE OF CONTENTS P ag e PREFACE ................................................................................................................. iv C h ap ter I. FOUNDATIONS IN FACT AND ALLUSION ............................. 1 n. SIR JOHN OLDCASTLE: HISTORY AND LEGEND . 16 m. THE HENRY IV PLAYS ................................................................. 55 IV. HENRY VI: PARTS I AND 2 ..................................................... 105 V. THE FAMOVS VICTORIES OF HENRY THE FIFTH . 144 VI. "ENTER: SIR JOHN RUSSELL AND HARVEY" . 177 Vn. THE A4ERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR ......................................... 204 EPILOGUE ................................................................................................................ 230 BIBLIOGRAPHY ..................................................................................................... 232 111 PREFACE Falstaff has been quite literally "the cause that wit is in other men. " The voluminous m aterials written on Shakespeare's most famous comic character equal, indeed, in the twentieth century surpass, the volumes written on Hamlet. It is, therefore, with a marked degree of tem erity that I add yet one more study to the overwhelming flood. To speak of provenance is simple. This study had its origin in a brief paper on the function of the comic characters in Shakespeare's Henry IV plays. -

![Historie of the [Drummond] Famil](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2204/historie-of-the-drummond-famil-6142204.webp)

Historie of the [Drummond] Famil

W^mr^r^ ~- &*»« %>$>Y <- .wfc. ^ ^»X^^£ y ^ ^ j^ ^ ^ g*w6.'«^ M >vi (v & J* *"~ig$LvWy Li » rffc, ( Jy. r K,. i+J\i£ . k^ w^ ^M ! v>*v,.,, I ArVU.4C- Vtf> J" , Oy Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://archive.org/details/genealogyofmostdOOdrum GENEALOGY OF THE HOUSE OF DRUMMOND This Fac-simile Reprint of Dr. David Laing's Edition of 1831, which ' has now become rare, is on Maitland Club ' paper, and the impression has been limited to One Hundred Copies. No. gang- TWvijxfu^ ^^4 r \\^ h \ i gj, ^ Xj qr cp.cpcp o» o„a ^fyeri(Lf7lUh to ±/^ Jiyfffcj&ffk WfrtnU ariif trewiii 7fffn*ra.l?lk Otrle Jncn £iuru $£ fierl.fi fyrcC '3ru??w?uC \^ (J£tZ TF $ u^L*^ \ W- (jnyiriCidi-^'yy^U.2 ^H \Z ?sl insi t/m Q ,4 r^ WU&JLjr^&JMT U>MU'JB£M~&jyjg)„ OF JFT.A WT1TOSJTDSM. THE GENEALOGY OF THE apoat J15cflle anD ancient $ouse of DRUMMOND By The Honourable WILLIAM DRUMMOND AFTERWARDS FIRST VISCOUNT OF STRATHALLAN 1681 GLASGOW PRIVATELY PRINTED MDCCCLXXXIX Printed by T. &° A. CONSTABLE, Printers to Her Majesty, at the Edinburgh University Press. THE GENEALOGY OF THE MOST NOBLE AND ANCIENT HOUSE OF DRUMMOND. BY THE HONOURABLE WILLIAM DRUMMOND, AFTERWARDS FIRST VISCOUNT OF STRATHALLAN, M.DC.LXXXI. EDINBURGH : M.DCCC.XXXI. PRINTED BY A. BALFOUR AND CO. r ','. - 1 ' c .-' M * ^JHE present Genealogical History, which is now printed for the first time, was com- piled in the year 1681, and has always been esteemed a work of authority. -

The Staggering State of Scottish Statesmen

427 THE STAGGERING STATE OF SCOTTISH STATESMEN. CHANCELLORS. i. James, Earl of Morton, Chancellor in Queen Mary's time, whose actions are at length set down in the histories of Buchanan and Knox, and Home's history of the family of Douglas, begot divers bastards, one of whom he made Laird of Spot, another Laird of Tofts. The first was purchased from his heirs by Sir Robert Douglas, and the last by one Belsches, an advocate. He was thereafter made regent in King James the VI.'s minority, anno 1572 ; but in that time was taxed with great avarice and extortion of the people, and by heightening the rate of money, and for coining of base coin, for adultery, and for delivering up the Earl of Northumberland to Queen Elizabeth, when he had fled to Scotland for refuge, being allured thereto by a sum of money.* He was overthrown by the means of the Earls of Argyle, Athole, and Montrose; and was accused and condemned for being art and part in the king's father's murder, which was proven by the means of Sir James Balfour, Clerk-Register, who produced his handwriting. He got a response to beware of the Earl of Arran, which he con- ceived to be the Hamiltons, and therefore was their perpetual enemy; but in this he was mistaken, seeing, by the furiosity of the Earl of Arran, Captain James Stewart was made his guardian, and afterwards became Earl of Arran, and by his moyenf Morton was condemned, and his head taken off at the market-cross of Edinburgh. -

The Heraldry of the Stewarts : with Notes on All the Males of the Family, Descriptions of the Arms, Plates and Pedigrees

/[ IXo , Scotland National Library of *B000279525* Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/heraldryofstewtsOOjohn THE Ukraldry of tbe Stewarts NOTE. 220 Copies of this Work have been printed, of which only 200 will be offered to the Public. 175 of these will form the Ordinary Edition, and 25 will be in Special Binding. THE heraldry of the Stewarts WITH NOTES ON ALL THE MALES OF THE FAMILY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE ARMS, PLATES AND PEDIGREES BY G. HARVEY JOHNSTON AUTHOR OF " SCOTTISH HERALDRY MADE EASY," ETC. ^JABLIS^ W. & A. K. JOHTtfSTON, LIM] EDINBURGH AND LONDON M C M V I WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR. 1. "The Ruddimans" (for private circulation). 2. "Scottish Heraldry Made Easy." 3. "The Heraldry of the Johnstons." DEDICATED BY PERMISSION TO THE STEWART SOCIETY. Introduction. THE name of Stewart is derived from the high office held by the earlier members of the family—namely, that of High Stewart of Scotland—and owing to the long connection of Scotland and France several members of the family went to the latter country. In the French alphabet there is no "w," and so " u " replaced it, the name thus becoming " Steuart," and as the " e " was then superfluous it was dropped, and the name was shortened into " Stuart." A branch of the family took the name of Menteth, which later became Menteith, Monteith, and Menteath. As regards the Armorial Bearings, the principal charge is the fess chequy or bend chequy —that is, a belt across the shield composed of rows, usually three, of squares, alternately blue and silver in the case of the Stewarts, and black and silver in that of the Menteths.