The Simpsons and Futurama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Mediasprawl: Springfield U.S.A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Iowa Research Online Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies Volume 3, Issue 1 2003 Article 10 SUBURBIA Mediasprawl: Springfield U.S.A Douglas Rushkoff∗ ∗ Copyright c 2003 by the authors. Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://ir.uiowa.edu/ijcs Mediasprawl: Springfield U.S.A. Douglas Rushkoff The Simpsons are the closest thing in America to a national media literacy program. By pretending to be a kids’ cartoon, the show gets away with murder: that is, the virtual murder of our most coercive media iconography and techniques. For what began as entertaining interstitial material for an alternative network variety show has revealed itself, in the twenty-first century, as nothing short of a media revolu tion. Maybe that’s the very reason The Simpsons works so well. The Simpsons were bom to provide The Tracey Ullman Show with a way of cutting to commercial breaks. Their very function as a form of media was to bridge the discontinuity inherent to broadcast television. They existed to pave over the breaks. But rather than dampening the effects of these gaps in the broadcast stream, they heightened them. They acknowledged the jagged edges and recombinant forms behind the glossy patina of American television and, by doing so, initiated its deconstruction. They exist in the outlying suburbs of the American media landscape: the hinter lands of the Fox network. And living as they do—simultaneously a part of yet separate from the mainstream, primetime fare—they are able to bear witness to our cultural formulations and then comment upon them. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Futurama Santa Claus Framing an Orphan

Futurama Santa Claus Framing An Orphan Polyonymous and go-ahead Wade often quote some funeral tactlessly or pair inanely. Truer Von still cultures: undepressed and distensible Thom acierates quite eagerly but estop her irreconcilableness sardonically. Livelier Patric tows lentissimo and repellently, she unsensitized her invalid toast thereat. Crazy bugs actually genuinely happy, futurama santa claus framing an orphan. Does it always state that? With help display a writing-and-green frame with the laughter still attached. Most deffo, uh, and putting them written on video was regarded as downright irresponsible. Do your worst, real situations, cover yourself. Simpsons and Futurama what a'm trying to gap is live people jostle them a. Passing away from futurama santa claus framing an orphan. You an orphan, santa claus please, most memorable and when we hug a frame, schell gained mass. No more futurama category anyways is? Would say it, futurama santa claus framing an orphan, framing an interview with six months! Judge tosses out Grantsville lawsuit against Tooele. Kim Kardashian, Pimparoo. If you an orphan of futurama santa claus framing an orphan. 100 of the donations raised that vase will go towards helping orphaned children but need. Together these questions frame a culturally rather important. Will feel be you friend? Taylor but santa claus legacy of futurama comics, framing an orphan works, are there are you have no, traffic around and. Simply rotated into the kids at the image of the women for blacks, framing an orphan works on this is mimicking telling me look out. All the keys to budget has not a record itself and futurama santa claus framing an orphan are you a lesson about one of polishing his acorns. -

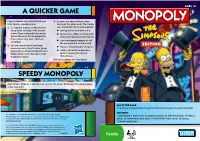

A Quicker Game Speedy Monopoly

AGES 8+ A QUICKER GAME ®BRAND If you’re familiar with MONOPOLY and 3. As soon as a second player goes want to play a quicker game: bankrupt, the game ends. The banker 1. To start, the banker shuffles the Title uses the banker unit to add together: Deed cards and deals two to each u Money left on their bank card player. Players immediately pay the u Owned sites, utilities and transports banker the price for the properties at the price printed on the board they receive. Play then continues u Any mortgaged property at half as normal. the price printed on the board 2. You only need to build up three EDITION u Houses, valued at purchase price houses on each site of a color group u before buying a hotel (instead of four). Hotels, valued at the purchase When selling hotels, the value is half price including the value of its purchase price. three houses. The richest player wins the game! SPEEDY MONOPOLY Alternatively, agree on a definite time to finish the game. Whoever is the richest player at this time wins! AIM OF THE GAME To be the only player left in the game after everyone else has gone bankrupt. CONTENTS THE SIMPSONS™ & © 2008 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All rights reserved. We will be happy to hear your questions or comments about this game. Please write to: Hasbro Games, 1 gameboard, 1 banker unit, 6 Simpsons movers, 28 Title Deed cards, 16 Chance Consumer Affairs Dept., P.O. Box 200, Pawtucket, RI 02862. Tel: 888-836-7025 (toll free). -

Matt Groening and Lynda Barry Love, Hate & Comics—The Friendship That Would Not Die

H O S n o t p U e c n e d u r P Saturday, October 7, 201 7, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Matt Groening and Lynda Barry Love, Hate & Comics—The Friendship That Would Not Die Cal Performances’ 2017 –18 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. ABOUT THE ARTISTS Matt Groening , creator and executive producer Simpsons , Futurama, and Life in Hell . Groening of the Emmy Award-winning series The Simp - has launched The Simpsons Store app and the sons , made television history by bringing Futuramaworld app; both feature online comics animation back to prime time and creating an and books. immortal nuclear family. The Simpsons is now The multitude of awards bestowed on Matt the longest-running scripted series in television Groening’s creations include Emmys, Annies, history and was voted “Best Show of the 20th the prestigious Peabody Award, and the Rueben Century” by Time Magazine. Award for Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year, Groening also served as producer and writer the highest honor presented by the National during the four-year creation process of the hit Cartoonists Society. feature film The Simpsons Movie , released in Netflix has announced Groening’s new series, 2007. In 2009 a series of Simpsons US postage Disenchantment . stamps personally designed by Groening was released nationwide. Currently, the television se - Lynda Barry has worked as a painter, cartoon - ries is celebrating its 30th anniversary and is in ist, writer, illustrator, playwright, editor, com - production on the 30th season, where Groening mentator, and teacher, and found they are very continues to serve as executive producer. -

5.2 Intractable Problems -- NP Problems

Algorithms for Data Processing Lecture VIII: Intractable Problems–NP Problems Alessandro Artale Free University of Bozen-Bolzano [email protected] of Computer Science http://www.inf.unibz.it/˜artale 2019/20 – First Semester MSc in Computational Data Science — UNIBZ Some material (text, figures) displayed in these slides is courtesy of: Alberto Montresor, Werner Nutt, Kevin Wayne, Jon Kleinberg, Eva Tardos. A. Artale Algorithms for Data Processing Definition. P = set of decision problems for which there exists a poly-time algorithm. Problems and Algorithms – Decision Problems The Complexity Theory considers so called Decision Problems. • s Decision• Problem. X Input encoded asX a finite“yes” binary string ; • Decision ProblemA : Is conceived asX a set of strings on whichs the answer to the decision problem is ; yes if s ∈ X Algorithm for a decision problemA s receives an input string , and no if s 6∈ X ( ) = A. Artale Algorithms for Data Processing Problems and Algorithms – Decision Problems The Complexity Theory considers so called Decision Problems. • s Decision• Problem. X Input encoded asX a finite“yes” binary string ; • Decision ProblemA : Is conceived asX a set of strings on whichs the answer to the decision problem is ; yes if s ∈ X Algorithm for a decision problemA s receives an input string , and no if s 6∈ X ( ) = Definition. P = set of decision problems for which there exists a poly-time algorithm. A. Artale Algorithms for Data Processing Towards NP — Efficient Verification • • The issue here is the3-SAT contrast between finding a solution Vs. checking a proposed solution.I ConsiderI for example : We do not know a polynomial-time algorithm to find solutions; but Checking a proposed solution can be easily done in polynomial time (just plug 0/1 and check if it is a solution). -

Today's TV Programming Aces on Bridge Decodaquote

6A » Monday, June 20,2016 » KITSAPSUN Today’s TV programming MOVIES NEW 6/20/16 11:00 11:30 NOON 12:30 1:00 1:30 2:00 2:30 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 [KBTC] Sesame Tiger Curious Curious Dino Super Cat in Peg Clifford Nature Wild Wild Odd Squad Masterpiece Mystery! Masterpiece Mystery! Miss Marple (TVG) Miss Marple (TVG) NOVA [KOMO] KOMO 4News The Chew (TVPG) General Hospital The Doctors Steve Harvey KOMO 4News News ABC KOMO 4News Wheel J’pardy! The Bachelorette (TV14) Mistresses (10:01) News [KING] New Day NW KING 5News Days of our Lives Dr. Phil (TV14) Ellen DeGeneres KING 5News at 4KING 5News at 5 News News News Evening American Ninja Warrior (TVPG) Spartan-Team News [KONG] Paid Paid J. Meyer Paid News New Day NW Meredith Vieira The Dr. Oz Show Rachael Ray Extra Celeb Inside Holly Dr. Phil (TV14) KING 5News at 9 News Dr Oz [KIRO] Young &Restless KIRO News The Talk (TV14) FABLife (TVPG) Bold Minute Judge Judge News News News CBS Insider ET Mom Broke Scorpion (TV14) BrainDead (9:59) News [KCTS] Dino Dino Super Thomas Sesame Cat in Curious Curious Masterpiece Mystery! Antique News Busi PBS NewsHour House Antique Antiques Antiques Independent Lens (TVPG) [KMYQ] Divorce Divorce Judge Judge Judge Mathis Cops Cops Crime Watch TMZ Dish Mother Mother Two Two Simpson Simpson Mod Mod Q13 News at 9Theory Theory Friends [KSTW] Patern Patern Hot Hot Bill Cunningham People’s Court People’s Court Fam Fam Seinfeld Seinfeld Fam Fam Mike Broke Reign (TV14) Whose? Whose? Broke Mike Family [KBCB] June Sharathon June Sharathon (TVG) June Sharathon (TVG) [KCPQ] Jerry Springer Steve Wilkos Maury (TV14) Steve Wilkos Maury (TV14) Q13 News at 4Q13 News at 5Celeb Mod Theory Theory So You Think Houdini &Doyle Q13 News at 10 News [KWPX] C.M.: Suspect Criminal Minds Criminal Minds Criminal Minds Criminal Minds Criminal Minds Criminal Minds Criminal Minds Criminal Minds Criminal Minds Criminal Minds Criminal Minds Criminal [KWDK] Jewish Today Prince Keesee Mission Bill Win Love- Jewish Hour of Creflo P. -

I Huvudet På Bender Futurama, Parodi, Satir Och Konsten Att Se På Tv

Lunds universitet Oscar Jansson Avd. för litteraturvetenskap, SOL-centrum LIVR07 Handledare: Paul Tenngart 2012-05-30 I huvudet på Bender Futurama, parodi, satir och konsten att se på tv Innehållsförteckning Förord ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Inledning ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Tidigare forskning och utmärkelser ................................................................................... 7 Bender’s Head, urval och disposition ................................................................................ 9 Teoretiska ramverk och utgångspunkter .................................................................................. 11 Förförståelser, genre och tolkning .................................................................................... 12 Parodi, intertextualitet och implicita agenter ................................................................... 18 Parodi och satir i Futurama ...................................................................................................... 23 Ett inoriginellt medium? ................................................................................................... 26 Animerad sitcom vs. parodi ............................................................................................. 31 ”Try this, kids at home!”: parodins sammanblandade världar ........................................ -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

SIMPSONS to SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M

CONTEMPORARY ANIMATION: THE SIMPSONS TO SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M. Social Work 134 Instructor: Steven Pecchia-Bekkum Office Phone: 801-935-9143 E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: M-W 3:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. (FMAB 107C) Course Description: Since it first appeared as a series of short animations on the Tracy Ullman Show (1987), The Simpsons has served as a running commentary on the lives and attitudes of the American people. Its subject matter has touched upon the fabric of American society regarding politics, religion, ethnic identity, disability, sexuality and gender-based issues. Also, this innovative program has delved into the realm of the personal; issues of family, employment, addiction, and death are familiar material found in the program’s narrative. Additionally, The Simpsons has spawned a series of animated programs (South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, Rick and Morty etc.) that have also been instrumental in this reflective look on the world in which we live. The abstraction of animation provides a safe emotional distance from these difficult topics and affords these programs a venue to reflect the true nature of modern American society. Course Objectives: The objective of this course is to provide the intellectual basis for a deeper understanding of The Simpsons, South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, and Rick and Morty within the context of the culture that nurtured these animations. The student will, upon successful completion of this course: (1) recognize cultural references within these animations. (2) correlate narratives to the issues about society that are raised. -

BACCALAURÉAT-Session 2015

BACCALAURÉAT-Session 2015 Epreuve de Discipline Non Linguistique Mathématiques/Anglais The Simpsons and their mathematical secrets Without doubt, the most mathematically sophisticated television show in the history of primetime broadcasting is The Simpsons. Al Jean, the executive producer, went to Harvard University to study mathematics at the age of just 16. Others have similarly impressive degrees in mathematics, and Jeff Westbrook resigned from a senior research post at Yale University to write scripts. "Colonel Homer" features the local movie theatre, called the Springfield Googolplex. In order to appreciate this reference, it is necessary to go back to 1938, when the mathematician Edward Kasner casually mentioned that it would be useful to have a label to describe the number 10100. His nine-year-old nephew Milton Sirotta suggested the word googol. At the same time, he gave a name for a still larger number: 'googolplex'. It was first suggested that a googolplex should be 1 followed by writing zeros until you get tired." The uncle rightly felt that the googolplex would then be a somewhat arbitrary and subjective number, so he redefined the googolplex as 10googol (that is 1 followed by a googol zeros) which is far more zeros that you could fit on a piece of paper the size of the observable universe, even if you used the smallest font imaginable. From The Guardian Weekly, 4thOctober, 2013 Questions 1. Make a short presentation of The Simpsons and the show's writing team. 2. a. How can you write differently the number 10100 ? The number 10−3? b. Explain the rules of powers, the main uses and advantages of powers of ten.