Technology Immorality and Its Legal Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

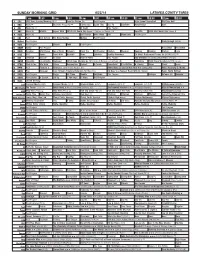

Sunday Morning Grid 6/22/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/22/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program High School Basketball PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Justin Time Tree Fu LazyTown Auto Racing Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Wildlife Exped. Wild 2014 FIFA World Cup Group H Belgium vs. Russia. (N) SportCtr 2014 FIFA World Cup: Group H 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Crazy Enough (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Wild Places Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Backyard 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA Grupo H Bélgica contra Rusia. (N) República 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA: Grupo H 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Austria. -

5 Inside CFP 4-2-09.Indd

FRIDAY APRIL 3 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 KLBY/ABC News (N) Enter- Wife Swap Mallick/ Supernanny Manley 20/20 (CC) News (N) Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live H h (CC) tainment Stewart (N) (CC) Family (CC) (CC) (N) (CC) Paul Walker. (CC) KSNK/NBC News (N) Wheel of Howie Howie Friday Night Lights Dateline NBC (CC) News (N) The Tonight Show Late L j Fortune Do It (N) Do It (N) Underdogs (N) (CC) With Jay Leno (CC) Night KBSL/CBS News (N) Inside Ghost Whisperer Flashpoint Aisle 13 NUMB3RS News (N) Late Show With Late FRIDAY1< NX (CC) Edition Big Chills (CC) (N) (CC) Blowback (CC) (CC) David LettermanAPRILLate3 K15CG The NewsHour Wash. Kansas Bill Moyers Journal Market- NOW on World New Red Charlie Rose (N) d With Jim Lehrer (N) Week Week (N) (CC) Market PBS (N) News Green (CC) ESPN Sports-6 PM NBA6:30 NBA7 P BasketballM 7:30: Cleveland8 P CavaliersM 8:30 at Orlando9 PM NBA9:30 Basketball10 PM: Houston10:30 Rockets11 at LosPM Angeles11:30 O_ Center Magic. Amway Arena. (Live) Lakers. Staples Center. (Live) KLBY/ABC News (N) Enter- Wife Swap Mallick/ Supernanny Manley 20/20 (CC) News (N) Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live HUSAh NCIS(CC) Goodtainment Wives HouseStewart You (N) (CC)Don’t HouseFamily (CC)Mirror Mirror House Ugly (CC) (CC)House Joy (N)(CC) (CC) PaulMovie: Walker. The Pacifier (CC) P^ Club (CC) Want to Know (CC) Hypochondriac. (CC) TT (2005) (CC) KSNK/NBC News (N) Wheel of Howie Howie Friday Night Lights Dateline NBC (CC) News (N) The Tonight Show Late LTBSj Seinfeld SeinfeldFortune FamilyDo It (N) FamilyDo It (N) Movie:Underdogs The (N) Mask (CC) TTT (1994, My Boys Sex and WithSex and Jay LenoMovie: (CC) TheNight Mask (CC) The Dog Guy (CC) Guy (CC) Comedy) (PA) Jim Carrey. -

Carryout GUIDE

PAID ECRWSS Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL (715) 479-4421 Wednesday, Jan. 6, 2021 6, Jan. Wednesday, AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW THE VILAS COUNTY SECTION OF SPECIAL A NORTH WOODS NORTH THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING WOODS OF NORTH BUNYAN THE PAUL © Eagle River Publications, Inc. 1972 Inc. Publications, 3620 N. Hwy. 47 Rhinelander, WI 715-420-1555 0 ALL TYPES OF NoNo MoneyMoneyDownDown**** CREDIT ACCEPTED** New Only 88K Leather We offer pick up and delivery Arrival! 2015 Ram 1500 Miles 2010 Ram Seats 2019 Jeep Big Horn 1500 TRX for Service, Test Drives and Renegade Vehicle Purchase. Limited Call us for more info. Service Department open BUY FOR BUY FOR BUY FOR until 7 p.m. Mon. & Wed. $21,999* $14,999* $23,999* Stock #M1058A Stock #P3967A Stock #L1020 *Advertised selling price includes applicable dis- counts and does not include tax, title, license $ † $ † $ † OR 391/MO. FOR 72 MOS. (1) OR 271/MO. FOR 72 MOS. (2) OR 425/MO. FOR 72 MOS. (3) or $299 service fee. For a Tour, Contact: Amy Gray **All vehicle offers including zero down with ap- All-Wheel New [email protected] 2017 GMC Arrival! 2014 Toyota 2013 Chevrolet proved credit to well-qualified buyers through Drive Acadia select lenders. RAV4 XLE Equinox † Monthly payment includes applicable dis- SLE counts. Rate, term and monthly payment of (1) LS $391 based on 5.2% for 72 months with $0 down; (2) $271 based on 5.2% for 72 months with $0 down; (3) $425 based on 5.2% for 72 months with $0 down; (4) $340 based on 5.2% for 72 months with $0 down; (5) $271 based BUY FOR BUY FOR BUY FOR on 5.2% for 72 months with $0 down; (6) $152 $18,999* $14,999* $7,999* based on 5.2% for 72 months with $0 down; Give the Gift of Life . -

UTAH BOARD of PARDONS and PAROLE DECISIONS REPORT from Wednesday, August 21, 2019 to Monday, September 30, 2019 Hearing Date: 2019-08-21

Run Date/Time: 10/01/2019 / 11:23 Page 1 of 391 UTAH BOARD OF PARDONS AND PAROLE DECISIONS REPORT from Wednesday, August 21, 2019 to Monday, September 30, 2019 Hearing Date: 2019-08-21 Offender # Offender Name Offender Hearing Type 189795 Tracy Lynn Winn SPECIAL ATTENTION REVIEW RESULTS Effective Date 1. CONTINUE ON PAROLE/ALTERNATIVE EVENT 08/21/2019 2. RIM: 3 DAY JAIL SANCTION APPROVED 08/21/2019 HEARING NOTES 1. RIM 3 DAY JAIL SANCTION APPROVED. AP&P to consider screening for Parole Violator Program on next violation. Offender # Offender Name Offender Hearing Type 140316 James Steven Sargetis REHEARING RESULTS Effective Date 1. REHEARING 11/01/2019 HEARING NOTES 1. Schedule Rehearing 11/2019 with updated medical report due to the Board of Pardons by 10/01/2019.*** Mr. Sargetis is expected to fully and completely participate in medical evaluation prior to Rehearing, failure to participate will result in further rehe Offender # Offender Name Offender Hearing Type 160441 Jesse Butcher ORIGINAL HEARING RESULTS Effective Date 1. PAROLE GRANTED 10/15/2019 AGREEMENT CONDITIONS 1. STANDARD PAROLE 2. BOPP MNTL HLTH/SUB ABUSE 3. GANG 4. Enter CCC until stabilized, which may include GPS monitoring. 5. Successfully complete educational and/or vocational training or other training as directed. 6. Complete Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to address criminogenic needs as identified in the risk and needs assessment. HEARING NOTES 1. Restitution in Case #151701940 to be returned to the sentencing court for verification, Judgment and Commitment notes that remaining financials have been sent to the Office of State Debt Collection. -

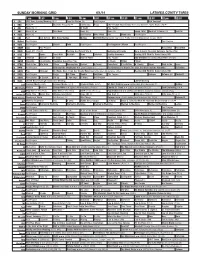

Sunday Morning Grid 6/1/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/1/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Press 2014 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Exped. Wild World of X Games (N) IndyCar 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: FedEx 400 Benefiting Autism Speaks. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program The Forgotten Children Paid Program 22 KWHY Iggy Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Heart 411 (TVG) Å Painting the Wyland Way 2: Gathering of Friends Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions For You (TVG) 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Healing ADD With Dr. Daniel Amen, MD 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto República Deportiva (TVG) El Chavo Fútbol Fútbol 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Walk in the Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

NBC Presents Kristin Chenoweth's

July 13 - 19, 2018 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad A M F S A Y P Y K A O R B S A 2 x 3" ad Q U S L W N U E A S T P E C K Your Key A R J L A V I N I A C D I O I To Buying G D A Y O M E J H D W A Y N E 2 x 3.5" ad V E K N W U B T A T R G X W N and Selling! U R T N A L E O L K M O V A H B O Y E R W S N Y T Z S E N Y L I W G O M H L C A H T U N I A I R N G W E O W V N O S E P F J E C V B P C L Y W T R L D I H O A J S H K A S M E S B O C X Y S Q U E P V R Y H M A E V F D C H O R F I W O V A D R A N W A M Y D R A X S L Y I R H P E H A I R L E S S E S O Z “Trial and Error” on NBC Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Lavinia (Peck-Foster) (Kristin) Chenoweth (New York) Lawyer Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Josh (Segal) (Nicholas) D’Agosto (Bizarre) Murder ad in the Waxahachie Daily Merchandise High-End Dwayne (Reed) (Steven) Boyer East Peck 2 x 3" ad Light, Midlothian1 x Mirror 4" ad and Deal Merchandise Carol (Anne Keane) (Jayma) Mays Flamboyant (Outfits) Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search Anne (Flatch) (Sherri) Shepherd Hairless (Cat) Call (972) 937-3310 NBC presents Run a single item Run a single item © Zap2it priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week Kristin Chenoweth’s 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light, 3.5" ad Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post Kristin Chenoweth stars in Season 2 of “Trial & Error,” and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

Movie Time Descriptive Video Service

DO NOT DISCARD THIS CATALOG. All titles may not be available at this time. Check the Illinois catalog under the subject “Descriptive Videos or DVD” for an updated list. This catalog is available in large print, e-mail and braille. If you need a different format, please let us know. Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service 300 S. Second Street Springfield, IL 62701 217-782-9260 or 800-665-5576, ext. 1 (in Illinois) Illinois Talking Book Outreach Center 125 Tower Drive Burr Ridge, IL 60527 800-426-0709 A service of the Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service and Illinois Talking Book Centers Jesse White • Secretary of State and State Librarian DESCRIPTIVE VIDEO SERVICE Borrow blockbuster movies from the Illinois Talking Book Centers! These movies are especially for the enjoyment of people who are blind or visually impaired. The movies carefully describe the visual elements of a movie — action, characters, locations, costumes and sets — without interfering with the movie’s dialogue or sound effects, so you can follow all the action! To enjoy these movies and hear the descriptions, all you need is a regular VCR or DVD player and a television! Listings beginning with the letters DV play on a VHS videocassette recorder (VCR). Listings beginning with the letters DVD play on a DVD Player. Mail in the order form in the back of this catalog or call your local Talking Book Center to request movies today. Guidelines 1. To borrow a video you must be a registered Talking Book patron. 2. You may borrow one or two videos at a time and put others on your request list. -

Breaking a Toxic Bond

C2 August 21 and August 22, 2021 LIFESTYLES The Daily Independent | Ashland, Kentucky Breaking TONIGHT'S TELEVISION AUGUST 21, 2021 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 a toxic BROADCAST CHANNELS WSAZ Health Divide (N) Stand Up to Cancer Live America-Talent Twelve performers take the stage WSAZ Saturday Night Live NBC with judging done by the American viewing audience. News (N) WLPX Law & Order: Special Law & Order: Special Law & Order: Special Law & Order: Special Law & Order: Special Law & Order: Special bond ION Victims Unit "Sick" Victims Unit "Lowdown" Victims Unit "Criminal" Victims Unit "Painless" Victims Unit "Bound" Victims Unit "Poison" Street Street American Bandits: Frank and Jesse James (2010) Wyatt Earp's Revenge (2012) Shawn Roberts, Val +++ One-Eyed Jacks TV-10 Dear Abby: I’m a 39-year- Magic Magic Tim Abell, Peter Fonda. 'TVPG' Kilmer. 'TVPG' (1961) 'TV14' old woman in a toxic rela- WCHS Paid Paid Stand Up to Cancer Live Shark Tank The Good Doctor Eyewitness :35 Full :05 Paid :35 Wrestle tionship with my boyfriend ABC Program Program "Venga" News (N) Measure Program of almost seven years. We WVAH 5:30 MLS Soccer Seattle vs Stand Up to Cancer Live Hell's Kitchen "More Eyewitness News at Game-Talents "Strings, Paid Family had a child together but lost FOX Columbus Than a Sticky Situation" 10:00 p.m. (N) Flaming Rings and Björn" Program Feud custody due to drug use dur- WOWK Mountaineer Game Day Stand Up to Cancer Live NCIS: New Orleans "We 48 Hours 13News- Inside WV Weather "Weathering the ing my pregnancy. -

Features & Entertainment ACTOR PAUL WALKER

PAGE TWO Features & Entertainment CANYON NEWS DECEMBER 8, 2013 ACTOR PAUL WALKER KILLED IN CAR CRASH CATCHING FIRE, FROZEN EXPLODE BOX-OFFICE By LaDale Anderson " ""By LaDale Ande"rson VALENCIA, CA—Actor Paul HOLLYWOOD—It was a busy Walker, best known for his weekend at the box-office role in the “Fast & Furious” over the Thanksgiving holi - movies was killed in a car day as the sequel to “The crash on Saturday, Novem - Hunger Games” and the Dis - ber 30. The crash occurred ney flick “Frozen” shattered at Hercules St. at Kelly box-office records. Any Johnson Pkwy near the guesses as to which picture 28300 block of Rye Canyon came out on top? To no sur - Loop, indicated the Los An - prise, “Catching Fire” con - geles Sheriff’s Department. tinued its dominance at the Santa Clarita Valley Sher - multiplex ranking in over iff’s Station traffic investi - $110 million during the five- gators have received eye - day weekend, bringing its to - Disney flim "Frozen" witness accounts indicating tal just a few mere million spot with $90 million. The over $14 million; at this point This weekend sees the re - the vehicle was traveling at from the $300 million mark film earned close to $74 mil - the picture has grossed more lease of the following indie a high rate of speed. The domestically. lion from Friday-Sunday. than $186 million domesti - flicks “Out of the Surface” posted speed limit in the The kiddies were definitely Landing in the third spot cally. The movie is certain to and “Inside Llewyn Davis” area is 45 mph. -

Ing in the Big Guns

September 6, 2019 ‘Wheel’ing in the big guns by Astyn Kennedy “I wanted to come here because Volume 3, Issue 1 it’s where I’m from,” Wheeler said. “It has an amazing Upcoming Events reputation, and we have great students and great parents.” 9/6 - FB vs. Fritch at In her free time, she enjoys 7:00pm watching Netflix and taking her son to baseball games and stock 9/7 - XC @ Thompson shows. When asked if there is Park Spearman ISD has been something she would like her experiencing a lot of changes students and faculty to know, she 9/13 - FB vs. Sunray lately. One of these changes announced her satisfaction with at 7:00pm includes a brand new principal, the school and those who attend Mrs. Sandi Wheeler. it. 9/14 - XC @ Canadian Wheeler grew up here in “I’ve been very impressed with the students and faculty and I 9/17 - Guest Speaker Spearman and graduated from appreciate everybody’s (All Campuses) this very high school. After high school, Wheeler received her open-mindedness about some of bachelor’s at North Western the changes we are making,” Oklahoma State University and Wheeler said. Sneak Peek: her master’s at Lamar Wheeler would like to express University. She has been working her gratitude to students and in the educational field for 16 faculty for giving her a chance, as **New Teachers years in many different schools, she hopes to improve the school (pgs. 1-4) including Stratford High School, to rise above the already-high Dalhart Elementary, and Liberal standard. -

Tuesday, September 15, Prime-Time: Broadcast Channels 7:30 Pm 8:00

Tuesday, September 15, Prime-time: Broadcast Channels 7:30 pm 8:00 pm 8:30 pm 9:00 pm 9:30 pm 10:00 pm 10:30 pm 11:00 pm 11:30 pm CBS Entertainment Big Brother (TVPG) Houseg- Love Island (TVPG) (N) Å FBI: Most Wanted (TV14) Å News Å Stephen Colbert Tonight (N) Å uests vie for the power of veto. (N) (11:35) Å (N) Å NBC All Access America’s Got Talent (TVPG) From Universal Studios, 11 semifinal- Transplant (TV14) (N) News Å Jimmy Fallon (TVPG) (N) Å ists perform. (N) Å Ewan McGre- gor. (N) Å CW 2 & 1/2 Men Dead Pixels Dead Pixels Tell Me a Story (TVMA) Jordan News Å Sports Final (N) News Å Friends (TV14) (TV14) Å Nicky’s father (TV14) Megan learns a shocking truth about (10:45) Å (11:35) Å tries to bond starts live the third pig; Hannah rushes with him by streaming back to New York to search for playing the from the Gabe, who is being held cap- game. (N) game. tive. (N) Å ABC Wheel of Fortune Modern Family Modern Family 20/20 Undecided voters, both in person and News Å News (N) Å Jimmy Kimmel (TVG) (N) Å Å (TVPG) Å virtually, ask President Donald Trump their im- Samuel L. portant questions before voting in November; Jackson hosts. anchored by George Stephanopoulos. (N) Å (11:35) Å KCAL Family Feud Å News Å News Å News Å Sports Central black-ish Å black-ish Å FOX Extra (TVPG) Hell’s Kitchen (TV14) Å Prodigal Son (TV14) Å News Å Extra (TVPG) TMZ (TVPG) Å MyNet Modern Family Chicago P.D.