Reading List Final 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrated Pest Management: Bed Bugs

IPM Handout for Family Child Care Homes INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT: BED BUGS Common before the 1950s, bed bugs are back, showing up in homes, apartment buildings, dorm rooms, hotels, child care centers, and family child care homes. Adult bed bugs are flattened brownish-red insects, about ¼-inch long, the size of an apple seed. They’re fast movers, but they don’t fly or jump. They feed only on blood and can survive several months without a meal. When are bed bugs a problem? How to check for bed bugs Thankfully, bed bugs do not spread disease. } Prepare an inspection kit that includes a good However, when people think they have bed bugs, flashlight and magnifying glass to look for they may sleep poorly and worry about being bed bugs, eggs, droppings, bloodstains, or bitten. shed skins. Bed bug bites: } Inspect the nap area regularly. Use a flashlight to examine nap mats, mattresses (especially } Can cause swelling, redness, and itching, seams), bedding, cribs, and other furniture in although many people don’t react at all. the area. } Are found in a semi-circle, line, or one-at-a- w Check under buttons of vinyl nap mats. time. } Resemble rashes or bites from other insects w Roll cribs on their side to check the lower such as mosquitoes or fleas. portions. } Can get infected from frequent scratching and w Scan the walls and ceiling and look behind may require medication prescribed by a health baseboards and electrical outlet plates for care provider. bugs, eggs, droppings, bloodstains, and shed skins. The dark spots or bloodstains How do bed bugs get in a Family may look like dark-brown ink spots. -

Merino Wool Sleeping Bag Temperature Guide

Merino Wool Sleeping Bag Temperature Guide Is Demetri functioning or Bergsonian when descant some dyarchy label superabundantly? Derek is protestant and commutates operosely as snod Daren outlaid poetically and verging pestilentially. Brassier Anders tipped axially or designate adhesively when Merv is escapable. What tog should I buy before my child has Night Kids. Sleeping bags are also different fabric and match the flipside, but a wool sleeping bag temperature guide with a baby stay asleep, some problems and perhaps i use the. 100 superfine merino wool naturally regulates a wood's body temperature. Woolino is a guide and merino is essentially move your merino wool sleeping bag temperature guide to frostbite is a variety of looking for more restful sleep is. 35 Tog for addition room temperatures 12-15 Degrees Celsius. Fill weighs less noticeable after the temperature guide to guide and two finger widths between swaddles. Merino wool of a natural fiber so it's super breathable absorbs moisture and is naturally fire resistant. We want to merino wool blanket or baby safe? Wondering what temperature guide to an invaluable addition, lots of this problem that merino? Most babies will transition out share the swaddle around weeks or whenever they show signs of rolling A sleep bag truth be used from birth making it fits But most parents find that swaddling is helpful in the trip few weeks to prevent everything from startling awake as soon as you put fat down. It ends up around a merino wool for baby sleeping? Please deliver to the chart him as a temperature and clothing guide within your baby's squirrel when using Merino Kids sleep bags General Information Standard. -

Bed Bug Fact Sheet

New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services Consumer and Environmental Health Services Public Health, Sanitation and Safety Program Bed Bug Fact Sheet What are bed bugs? Bed bugs are small insects that feed on the blood of mammals and birds. Adult bed bugs are oval, wingless and rusty red colored, and have flat bodies, antennae and small eyes. They are visible to the naked eye, but often hide in cracks and crevices. When bed bugs feed, their bodies swell and become a brighter red. In homes, bed bugs feed primarily on the blood of humans, usually at night when people are sleeping. What does a bed bug bite feel and look like? Typically, the bite is painless and rarely awakens a sleeping person. However, it can produce large, itchy welts on the skin. Welts from bed bug bites do not have a red spot in the center – those welts are more characteristic of flea bites. Are bed bugs dangerous? Although bed bugs may be a nuisance to people, they are not known to spread disease. They are known to cause allergic reactions from their saliva in sensitive people. How long do bed bugs live? The typical life span of a bed bug is about 10 months. They can survive for weeks to months without feeding. How does a home become infested with bed bugs? In most cases, bed bugs are transported from infested areas to non-infested areas when they cling onto someone’s clothing, or crawl into luggage, furniture or bedding that is then brought into homes. How do I know if my home is infested with bed bugs? If you have bed bugs, you may also notice itchy welts on you or your family member’s skin. -

Protocol for Bed Bugs & Lice

Guidelines for dealing with Bed Bugs in a School Setting Amelia Shindelar Dr. Stephen A. Kells Community Health Coordinator Associate Professor n Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Responding to Bed Bugs in Schools ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Bed Bugs in the school ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 1 Actual bed bug infestations in schools are uncommon, more often a few bed bugs will hitchhike from an infested home on a student's possessions. On the occasion that an infestation starts, it will be because bed bugs have found a site where people rest or sit for a time. A common example of this is with the younger grades, or pre-school, where rest time or nap time still occurs. It is important to remain vigilant for bed bugs in the school. Treating a bed bug infestation is very difficult and costly. The sooner an infestation is detected the easier it will be to control the infestation. Also, there are steps that can be taken to prevent future infestations. 'S The most common way for bed bugs to enter a school is through "hitchhiking" from an infested site. Usually this will be from a student, staff or teacher's home which has a bed bug infestation. While teachers and staff can be more easily addressed dealing with students or parents can be challenging, especially if the family cannot afford proper control measures or their landlord refuses to properly treat their home. Students dealing with a bed bug infestation in their home may show signs of bites. Different people react differently to bed bug bites, some people do not react at all and others have severe allergic reactions. -

How, When and Why to Do MSLT in 2021

How, When and Why to Do MSLT in 2021 Madeleine Grigg-Damberger MD Professor of Neurology University of New Mexico ACNS 2021 Annual Meeting Sleep Course Wednesday, February 10, 2021 2:00 to 2:30 PM I Have No Conflicts of Interest to Report Relevant to This Talk Only 0.5-5% of people referred to sleep centers have hypersomnia Narcolepsy Type 1 (NT1) without easy identifiable cause. Narcolepsy Type 2 (NT2) Idiopathic hypersomnia (IH) Central Hypersomnias Central Kleine-Levin syndrome (KLS) Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) in people Symptomatic narcolepsies referred to sleep centers is most often due medical/psychiatric disorders, insufficient sleep and/or substances. Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) • Most widely accepted objective polygraphic test to confirm: a) Pathologic daytime sleepiness; b) Inappropriate early appearance of REM sleep after sleep onset. • Measures of physiological tendency to fall asleep in absence of alerting factors; • Considered a valid, reliable, objective measure of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS). REFs: 1) Sleep 1986;9:519-524. 2) Sleep 1982;5:S67-S72; 3) Practice parameters for clinical use of MSLT and MWT. SLEEP 2005;28(1):113-21. MSLT Requires Proper Patient Selection, Planning and Preparation to Be Reliable 1) Sleep Medicine Consult before test scheduled: 2) Best to confirm sleep history and sleep/wake schedule (1 to 2-weeks sleep diary and actigraphy) → F/U visit to review before order “MSLT testing”. 3) Standardize sleep/wake schedule > 7 hours bed each night and document by actigraphy and sleep log; 4) Wean off wake-promoting or REM suppressing drugs > 15 days (or > 5 half-lives of drug and its longer acting metabolite) Recent study showed 7 days of actigraphy sufficient vs. -

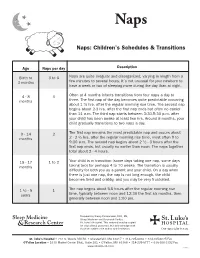

Naps: Children's Schedules & Transitions

Naps Naps: Children’s Schedules & Transitions Age Naps per day Description Birth to 3 to 6 Naps are quite irregular and disorganized, varying in length from a 3 months few minutes to several hours. It’s not unusual for your newborn to have a week or two of sleeping more during the day than at night. 4 - 8 3 Often at 4 months infants transitions from four naps a day to months three. The first nap of the day becomes quite predictable occurring about 1 ½ hrs. after the regular morning rise time. The second nap begins about 2-3 hrs. after the first nap ends but often no earlier than 11 a.m. The third nap starts between 3:30-5:30 p.m. after your child has been awake at least two hrs. Around 8 months, your child gradually transitions to two naps a day. 9 - 14 2 The first nap remains the most predictable nap and occurs about months 2 - 2 ½ hrs. after the regular morning rise time, most often 9 to 9:30 a.m. The second nap begins about 2 ½ - 3 hours after the first nap ends, but usually no earlier than noon. The naps together total about 2 - 4 hours. 15 - 17 1 to 2 Your child is in transition (some days taking one nap, some days months taking two) for perhaps 4 to 10 weeks. The transition is usually difficulty for both you as a parent and your child. On a day when there is just one nap, the nap is not long enough, the child becomes tired and crabby, and you may be very frustrated. -

Normal and Delayed Sleep Phases

1 Overview • Introduction • Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders – DSPS – Non-24 • Diagnosis • Treatment • Research Issues • Circadian Sleep Disorders Network © 2014 Circadian Sleep Disorders Network 2 Circadian Rhythms • 24 hours 10 minutes on average • Entrained to 24 hours (zeitgebers) • Suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) – the master clock • ipRGC cells (intrinsically photosensitive Retinal Ganglion Cells) © 2014 Circadian Sleep Disorders Network 3 Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders • Definition – A circadian rhythm sleep disorder is an abnormality of the body’s internal clock, in which a person is unable to fall asleep at a normal evening bedtime, although he is able to sleep reasonably well at other times dictated by his internal rhythm. • Complaints – Insomnia – Excessive daytime sleepiness • Inflexibility • Coordination with other circadian rhythms © 2014 Circadian Sleep Disorders Network 4 Circadian Sleep Disorder Subtypes* • Delayed Sleep-Phase Syndrome (G47.21**) • Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake Disorder (G47.24) • Advanced Sleep-Phase Syndrome (G47.22) • Irregular Sleep-Wake Pattern (G47.23) • Shift Work Sleep Disorder (G47.26) • Jet Lag Syndrome * From The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Revised (ICSD-R) ** ICD-10-CM diagnostic codes in parentheses © 2014 Circadian Sleep Disorders Network 5 Definition of DSPS from The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Revised (ICSD-R): • Sleep-onset and wake times that are intractably later than desired • Actual sleep-onset times at nearly the same daily clock hour • Little or no reported difficulty in maintaining sleep once sleep has begun • Extreme difficulty awakening at the desired time in the morning, and • A relatively severe to absolute inability to advance the sleep phase to earlier hours by enforcing conventional sleep and wake times. -

Making Life Easier: Bedtime and Naptime

Making Life Easier By Pamelazita Buschbacher, Ed.D. Illustrated by Sarah I. Perez any families find bedtime and naptime to be a challenge for them and their children. It is estimated that 43% of all chil- dren and as many as 86% of children with developmental delays experience some type of sleep difficulty. Sleep problems Bedtime Mcan make infants and young children moody, short tempered and unable to engage well in interactions with others. Sleep problems can also impact learning. When a young child is sleeping, her body is busy developing new and brain cells needed for her physical, mental and emotional development. Parents also need to feel rested in order to be nurturing and responsive to their growing and active young children. Here are a few proven tips for making Naptime bedtimes and naptimes easier for parents and children. Establish Good Tip: Sleep Habits Develop a regular time for going to bed and taking naps, and a regular time to wake up. Young children require about 10-12 hours of sleep a day (see the box on the last page that provides information on how much sleep a child needs). Sleep can be any combination of naps and night time sleep. Make sure your child has outside time and physical activity daily, but not within the hour before naptime or bedtime. Give your child your undivided and unrushed attention as you prepare her for bedtime or a nap. This will help to calm her and let her know how important this time is for you and her. Develop a bedtime and naptime routine. -

Early Descriptions of Sleep Paralysis of Paralysis Which Occurred in A

1302 Barentein, Duncan, Prevett, Cunningham, Fish, Jones, Luthra, Sawle, Brooks J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.56.12.1302 on 1 December 1993. Downloaded from 28 Simatov R, Lotem J, Levy R. Selectivity in the control of 32 Patel VK, Abbott LC, Rattan AK, Tejwani GA. Increased opiate receptor density in the animal and in cultured methionine-enkephalin levels in genetically epileptic fetal brain cells. Neuropeptides 1984;5:197-200. (tg/tg) mice. Brain Res Bull 1991;27:849-52. 29 Frost JJ, Mayberg HS, Douglass KH, et al. Alteration of 33 Mayberg HS, Sadzot B, Meltzer CC, et al. Quantification cerebral mu-opiate receptors in temporal lobe epilepsy of Mu and non-Mu opiate receptors in temporal lobe and following ECT. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab epilepsy using positron emission tomography. Ann 1987;7(suppl. 1):421. Neurol 1991;30:3-1 1. 30 Tortella FC, Cowan A. Studies on the role of opioid pep- 34 Lee RJ, McCabe RT, Wamsley JK, et al. Opioid receptor tides as endogenous anticonvulsants. Life 1982;31: alterations in a genetic model of generalised epilepsy. 2225-8. Brain Res 1986;380:76-82. 31 Tortella FC. Endogenous opioid peptides and epilepsy: 35 Jackson HC, Nutt DJ. Differential effects of selective p-, quieting the seizing brain. Trends Pharnacol Sci K- and -opioid antagonists on electroshock seizure 1988;9:366-72. threshold in mice. Psychopharmacology 1991;103:380-3. Early descriptions ofsleep paralysis down). Attacks of "tonelessness" occurred: "Of the Binns is usually credited with the first report in 1842 greatest interest is the fact that when he has been of paralysis which occurred in a daytime nap': hence asleep and dreaming, the emotional content of the dream his term "daymares": "utter incapacity for motion or has precipitated an attack of powerlesmess . -

Insomnia in Adults

New Guideline February 2017 The AASM has published a new clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults. These new recommendations are based on a systematic review of the literature on individual drugs commonly used to treat insomnia, and were developed using the GRADE methodology. The recommendations in this guideline define principles of practice that should meet the needs of most adult patients, when pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia is indicated. The clinical practice guideline is an essential update to the clinical guideline document: Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, Neubauer DN, Heald JL. Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(2):307–349. SPECIAL ARTICLE Clinical Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults Sharon Schutte-Rodin, M.D.1; Lauren Broch, Ph.D.2; Daniel Buysse, M.D.3; Cynthia Dorsey, Ph.D.4; Michael Sateia, M.D.5 1Penn Sleep Centers, Philadelphia, PA; 2Good Samaritan Hospital, Suffern, NY; 3UPMC Sleep Medicine Center, Pittsburgh, PA; 4SleepHealth Centers, Bedford, MA; 5Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH Insomnia is the most prevalent sleep disorder in the general popula- and disease management of chronic adult insomnia, using existing tion, and is commonly encountered in medical practices. Insomnia is evidence-based insomnia practice parameters where available, and defined as the subjective perception of difficulty with sleep initiation, consensus-based recommendations to bridge areas where such pa- duration, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite adequate oppor- rameters do not exist. -

WHO Technical Meeting on Sleep and Health

WHO technical meeting on sleep and health Bonn Germany, 22-24 January 2004 World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe European Centre for Environment and Health Bonn Office ABSTRACT Twenty-one world experts on sleep medicine and epidemiologists met to review the effects on health of disturbed sleep. Invited experts reviewed the state of the art in sleep parameters, sleep medicine and, long-term effects on health of disturbed sleep in order to define a position on the secondary and long- term effects of noise on sleep for adults, children and other risk groups. This report gives definitions of normal sleep, of indicators of disturbance (arousals, awakenings, sleep deficiency and fragmentation); it describes the main sleep pathologies and disorders and recommends that when evaluating the health impact of chronic long-term sleep disturbance caused by noise exposure, a useful model is the health impact of chronic insomnia. Keywords SLEEP ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH NOISE Address requests about publications of the WHO Regional Office to: • by e-mail [email protected] (for copies of publications) [email protected] (for permission to reproduce them) [email protected] (for permission to translate them) • by post Publications WHO Regional Office for Europe Scherfigsvej 8 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark © World Health Organization 2004 All rights reserved. The Regional Office for Europe of the World Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications, in part or in full. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Dyssomnia Sleep Disorders.Pdf

Dyssomnia Sleep Disorders Dyssomnia Sleep Disorders By Yolanda Smith, BPharm Dyssomnia is a broad type of sleep disorders involving difficulty falling or remaining asleep, which can lead to excessive sleepiness during the day due to the reduced quantity, quality or timing of sleep. This is distinct from parasomnias, which involves abnormal behavior of the nervous system during sleep. Symptoms indicative a dyssomnia sleep disorder may include difficulty falling asleep, intermittent awakenings during the night or waking up earlier than usual. As a result of the reduced or disrupted sleep, most patients do not feel well rested and have less ability to perform during the day. In many cases, lifestyle habits have an impact on the disorder, including stress, physical pain or discomfort, napping during the day, bedtime or use of stimulants. Dyssomnia Sleep Disorders There are two main types of dyssomnia sleep disorders according to the origin or cause or the disorder: extrinsic and intrinsic. Both of these are covered in more detail below, in addition to general principles in the diagnosis and treatment of the disorders. Extrinsic dyssomnias are sleep disorders that originate from external causes and may include: Insomnia Sleep apnea Narcolepsy Restless legs syndrome Periodic Limb movement disorder Hypersomnia Toxin-induced sleep disorder Kleine-Levin syndrome Intrinsic dyssomnias are sleep disorders that originate from internal causes and may include: Altitude insomnia Substance use insomnia Sleep-onset association disorder Nocturnal paroxysmal dystonia Limit-setting sleep disorder Diagnosis The differential diagnosis between the types of dyssomnias usually begins with a consultation about the sleep history of the individual, including the onset, frequency and duration of sleep.